Abstract

Background. Women with breast cancer experience different symptoms related to surgical or adjuvant therapy. Previous findings and theoretical models of mind–body interactions suggest that psychological wellbeing, i.e. levels of distress, influence the subjective evaluation of symptoms, which influences or determines functioning. The eight-week mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) program significantly reduced anxiety and depression in breast cancer patients in a randomized controlled trial (NCT00990977). In this study we tested the effect of MBSR on the burden of breast cancer related somatic symptoms, distress, mindfulness and spiritual wellbeing and evaluated possible effect modification by adjuvant therapy and baseline levels of, distress, mindfulness and spiritual wellbeing.

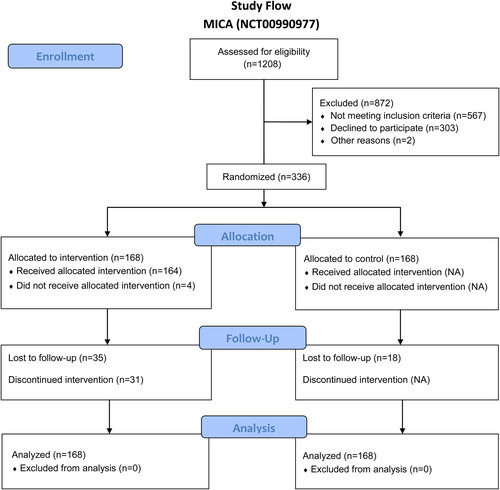

Material and methods. A population-based sample of 336 women Danish women operated for breast cancer stages I–III were randomized to MBSR or usual care and were followed up for somatic symptoms, distress, mindfulness skills and spiritual wellbeing post-intervention and after six and 12 months. Effect was tested by general linear regression models post-intervention, and after six and 12 months follow-up and by mixed effects models for repeated measures of continuous outcomes. Effect size (Cohen's d) was calculated to explore clinical significance of effects among intervention group. Finally, modification of effect of MBSR on burden of somatic symptoms after 12 months’ follow-up by adjuvant therapy and baseline levels of, distress, mindfulness and spiritual wellbeing were estimated.

Results. General linear regression showed a significant effect of MBSR on the burden of somatic symptoms post-intervention and after 6 months’ follow-up. After 12 months’ follow-up, no significant effect of MBSR on the burden of somatic symptoms was found in mixed effect models. A statistically significant effect of MBSR on distress was found at all time-points and in the mixed effect models. Significant effects on mindfulness were seen after six and 12 months and no significant effect was observed for spiritual wellbeing. No significant modification of MBSR effect on somatic symptom burden was identified.

Conclusion. This first report from a randomized clinical trial on the long-term effect of MBSR finds an effect on somatic symptom burden related to breast cancer after six but not 12 months follow-up providing support for MBSR in this patient group.

Women operated for breast cancer experience different symptoms related to surgical or adjuvant therapy [Citation1]. Theoretical models and empirical evidence of mind–body interactions suggest that psychological wellbeing, i.e. levels of distress, influence the subjective evaluation of symptoms, which influences or determines functioning [Citation2]. On the basis of this rationale, psychological interventions have been used to minimize the negative effects of treatment-related symptoms in women treated for breast cancer [Citation3]. Factors like spiritual wellbeing have also been found to be associated with self-reported levels of symptoms – both psychological and physiological [Citation4].

Mindfulness, the cultivation of a kind of attention characterized by non-judgmental awareness, openness, curiosity and acceptance of present internal and external experiences, is rooted in Buddhism. Mindfulness has been defined as the ability to be aware of the present moment on purpose and without judging by Jon Kabat-Zinn at the University of Massachusetts Medical Center, who westernized the concept and developed the mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) program in 1979 [Citation5]. MBSR is a group-based intervention delivered by trained instructors as eight weekly 2–2½-h sessions covering mindfulness meditation practice, gentle yoga and education on the psychological and physiological aspects of stress. The program includes a full-day silent retreat and a recommendation for 45-min daily home practice between sessions.

The aim of the MBSR program is to increase participants’ ability to experience thoughts, feelings and bodily sensations as they arise, by counteracting avoidance and developing greater emotional tolerance. MBSR participants learn to turn towards and accept intense bodily sensations and emotional discomfort. The aim of the formal [meditation, breathing exercises and yoga] and informal [walking meditation, contemplation] practice of mindfulness within MBSR is to increase participants’ attention skills to allow them to recognize automatic activation of dysfunctional thought processes and to disengage themselves from those processes by redirecting their attention to the experience of the present moment. By improving the acceptance of symptoms, increasing meta-reflective capacity and enhancing the freedom of patients, the practice of mindfulness potentially changes perception, behavior patterns and thereby the experience of symptoms [Citation6].

Systematic reviews and meta-analyses of trials in a variety of clinical non-cancer and non-clinical samples have shown that MBSR has beneficial effects on psychosocial outcomes and physiological processes and symptoms [Citation7,Citation8]. Meta-analysis of trials with cancer patients has shown significant effects of MBSR on psychosocial outcomes [Citation6]. Trials in breast cancer patients, both randomized (N = 86–214) and uncontrolled, have shown positive effects on anxiety, depression, coping, quality of life, and perceived stress [Citation8].

We conducted a randomized controlled trial of the effect of MBSR in 336 Danish women after surgery for breast cancer. We previously reported statistically significantly lower levels of the primary outcomes anxiety and depression in the intervention group throughout 12 months of follow-up [Citation9], contributing to the robust effect of MBSR on anxiety and depression identified in a recent meta-analysis of studies of more than 900 patients [Citation6]. Smaller trials among breast cancer patients (N = 59–84) [Citation10,Citation11] have shown an effect of MBSR on somatic symptoms. The aim of the current study was to determine the effect of MBSR on the burden of self-reported somatic symptoms related to breast cancer as well as on distress, mindfulness and spiritual wellbeing. Further, to determine any modification of the effect on somatic symptoms by adjuvant therapy, or by baseline levels of mindfulness factors, distress and spiritual wellbeing.

Material and methods

The MICA trial is registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov (identifier: NCT00990977), and approved by the Danish Data Protection Board (2007-41-1654).

Participants

Women were eligible for the trial if aged 18–75 years and operated for stage I–III breast cancer at one of the two specialized breast surgery departments in which patients were recruited to the study and had received their diagnosis 3–18 months earlier. The exclusion criteria were current major psychiatric disease or another medical condition that would limit participation, insufficient Danish language to fill in a questionnaire, or a diagnosis of another cancer within 10 years. The baseline characteristics of the eligible patients that allow evaluation of the external validity of the MICA trial have been presented elsewhere [Citation12]. Usual care control included no specific psychosocial intervention. Both study groups received standard clinical care, surgery, and adjuvant treatment as indicated by the relevant protocol or clinical guideline [Citation13], as the tax-financed Danish healthcare system gives all residents free access to hospital in- and outpatient care.

MBSR

The intervention group was assigned to MBSR courses based on the original manual, i.e. eight weekly 2-h group sessions of training, including guided meditation, yoga and psycho-educational advice on stress and stress reactions, group dialogue on integration of mindfulness practice into daily life and a 5-h silent retreat [Citation14]. The course instructor scheduled pre-course personal interviews with each participant to introduce mindfulness, present the course outline, explain training recommendations, and answer questions. A yoga mat, four audio CDs of guided meditation, and a course folder containing assignments and didactic material on stress and yoga were provided at the first session. During the intervention period from March 2008 up until November 2009 a total of seven MBSR courses were delivered. Courses were administered among 12–30 participants by one of three clinical psychologists all with through training as mindfulness instructors. One instructor delivered one course and another three courses. A senior instructor (AS) delivered three courses, and also supervised the other instructors to ensure fidelity to the MBSR curriculum.

Outcomes were measured on validated psychometric scales scored according to manuals. The 30-item Breast Cancer Prevention Trial eight-symptom checklist (BCPT) [Citation15,Citation16] was used to assess somatic symptoms related to breast cancer and its treatment (cognitive symptoms, pain, vasomotor symptoms, nausea, sexual or bladder problems, body image, and vaginal symptoms). Here, we report the symptom burden index calculated from all items, which is a measure of the individuals’ total symptom burden, higher scores indicating more burden. Distress was measured on the Danish version of the Symptom Checklist 90-r (SCL-90r) [Citation17], which has nine subscales or indexes; scores for the general stress index, which contains 90 items indicating level of distress, are reported here. We report scores on the 37-item ‘five facet mindfulness questionnaire’ (FFMQ), with a total score summarizing scores on the five subscales for central mindfulness skills (observing, describing, acting with awareness, non-judging and non-reactivity to inner experience), higher scores reflecting greater ability [Citation18]. To account for missing items, we report a mean FFMQ score (sum total of non-missing items/number of non-missing items) was calculated at each time point [Citation19]. We measured spiritual wellbeing by use of FACIT-Sp, a 12-item measure of spiritual wellbeing, higher scores indicating greater levels of peace, meaningfulness and faith [Citation20].

Sample size was determined as a minimal detectable difference of 10%, a power of 0.80 and an alpha of 0.05, and we aimed to include 300 patients with follow-up after 12 months. On the basis of previous findings on participant attrition [Citation21], we included 336 patients.

Enrolment of eligible women was initiated by mailed invitation to participate in the study, including an information letter, the study questionnaire, a consent form, and a pre-stamped return envelope. When a filled-in questionnaire and written consent were returned to the study group, the participant was telephoned by a research assistant, who provided oral information and obtained oral consent. Consenting patients were randomized (1:1) via a web interface by use of computer-generated sequences of 10 patients. Intervention participants were consecutively allocated to one of 10 MBSR courses. Allocation to courses, and thus the care provider, was pragmatic and based on the rate of randomization of patients to the intervention group, with 12–30 patients assigned to each course.

Follow-up questionnaires were mailed to participants according to the time of intervention of each participant two, six and 12 months after the start of the intervention. The timing of sending questionnaires to controls was determined by linking each control patient to the next patient randomized to MBSR. Follow-up questionnaires (and up to two written reminders) were sent to all participants, unless the patient or a relative sent a message of no interest (withdrawal) ().

Statistical methods

All psychometric scales were scores according to convention and missing data were imputed for the conduct of the mixed procedures by last observation carried forward.

Mean values and standard deviations were calculated for continuous variables and counts and proportions for categorical ones. Differences between the study groups for all baseline characteristics and outcomes were analyzed separately. A general linear regression model was used to analyze differences in the group mean change between baseline and immediately after the intervention, after six months’ follow-up and after 12 months’ follow-up. To evaluate the effect of the study group on the level of outcome (symptom burden, distress, mindfulness skills and spiritual wellbeing), mixed effect models for repeated measures of continuous outcomes were fitted. This analytic approach can be applied to longitudinal data with missing observations in time and inherently accounts for correlations associated with repeated measurements. The regression approach was performed for each outcome in an intention-to-treat analysis of the total sample, regardless of missing data, as an intention-to-treat analysis including participants with full follow-up, and as a sensitivity analysis by the last-observation-carried-forward procedure [Citation22]. Study center, time since diagnosis and baseline levels of outcomes were included as covariates in the model.

To evaluate clinical significance size of the effect of MBSR on somatic symptoms, distress, mindfulness and spiritual wellbeing Cohen's d was calculated for the intervention group as the difference between baseline mean score and mean score after 12 months divided by the pooled standard deviation with regard to each outcome.

To evaluate modification of the effect of MBSR on the burden of symptoms by type of adjuvant therapy (chemo-, radiation or hormonal), baseline values of distress, mindfulness skills and spiritual wellbeing, interactions between study group and these variables were included in all three intention-to-treat analyses. Statistical analyses were pre-specified by registration of the trial and performed with SAS, version 9.1.

Results

Within the inclusion period (June 2007–February 2009) a total of 336 women were randomized to MBSR (N = 168) or treatment as usual (N = 168). No harm was identified and the trial was ended according to plan. Questionnaires and/or reminders were mailed to participants up until 14 months after last MBSR session. As analysis of baseline characteristics revealed no significant between-group differences, the randomization was deemed to be balanced (). Descriptive analysis revealed a statistically significant mean decrease in the burden of somatic symptoms between baseline and immediately after the intervention among MBSR participants and a mean increase among control participants (p = 0.01). This difference was maintained at the six months’ follow-up (p = 0.002). After 12 months, no significant between-group difference was seen (p = 0.22) ().

Table I. Baseline characteristics of 336 women enrolled in a randomized controlled trial of mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR), Copenhagen, 2008–2010 (the MICA trial).

Table II. Effect of mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) on burden of somatic symptoms, distress, mindfulness skills and spiritual wellbeing, Copenhagen, 2008–2010 (the MICA trial).

A statistically significant greater reduction in distress was found among MBSR participants immediately (p = 0.01) and after six (p < 0.001) and 12 months’ follow-up (p = 0.04). Statistically significantly higher levels of mean mindfulness skills were observed only after six months (p = 0.01 (). Both study groups reported a mean increase in spiritual wellbeing, with a statistically significant difference after six months (p = 0.02) but no significant difference was seen after 12 months of follow-up (p = 0.11) ().

Clinical significance of the MBSR intervention was explored by use of Cohen's d and small effects were identified with regard to burden of somatic symptoms (0.25), mindfulness skills (0.21) and spiritual wellbeing (0.22), while a medium effect (0.43) was identified with regard to distress ().

To evaluate the longer term effect of MBSR, mixed models were fitted. Statistically significant differences in levels of distress were identified in models that included all the available data (p = 0.003), data from participants after 12 months’ follow-up (p = 0.003), and with the last-observation-carried-forward procedure (p = 0.03). No statistically significant effect on the burden of somatic symptoms, mindfulness skills (mean or overall) or spiritual wellbeing was found (p = 0.1–0.9) (). No modification of effect of MBSR on somatic symptoms by adjuvant therapy or baseline levels of distress, mindfulness or spiritual wellbeing was identified ().

Table III. Effect of mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) on burden of somatic symptoms, distress, mindfulness and existential wellbeing among Danish women operated on for breast cancer, Copenhagen, 2008–2010 (the MICA trial).

Table IV. Modification of effect of mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) on burden of somatic symptoms after 12 months’ follow-up by adjuvant therapy and baseline levels of, distress, mindfulness and existential wellbeing among Danish women operated on for breast cancer, Copenhagen, 2008–2010 (the MICA trial).

Discussion

While statistically significant effect of MBSR on level of distress was identified after 12 months follow-up in this study of Danish women with breast cancer randomized to MBSR or usual treatment there was no statistically significant effect on burden of somatic symptoms at this time-point. Regression analyses at six months follow-up did however identify a difference in mean change since baseline between groups on somatic symptom burden, distress, mindfulness skills and spiritual wellbeing.

Our findings of an effect of MBSR on somatic symptom burden post-intervention and at six months are in line with that of a recent waiting-list-controlled randomized trial of MBSR in 229 women with breast cancer [Citation23], which showed statistically significantly more improvement in physical wellbeing, as a secondary outcome, among MBSR participants than wait-list controls in a per-protocol analysis after three months’ follow-up. As noted by the authors, this study included only women with a self-identified need for psychosocial care, who had sought out psychological services outside the clinical setting. Thus, our findings based on intention-to-treat analyses give new support for use of MBSR to alleviate the burden of highly prevalent breast cancer-related somatic symptoms. Analysis of the effects of MBSR on women with the greatest burden of physical symptoms would violate the randomized design and was thus not done. To obtain more insight into the effect of MBSR on levels of somatic symptoms after longer follow-up, future studies should establish cut-off baseline levels of somatic symptoms or stratify randomized participants by burden of symptoms [Citation24].

This is, to the best of our knowledge, the first randomized controlled trial of MBSR among breast cancer patients in which levels of mindfulness skills are reported. We identified statistically significant between-group differences in mindfulness skills after six months’ follow-up by use of the FFMQ. A recent meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials of mindfulness-based therapy (including MBSR) among breast cancer patients (including the current sample) showed a statistically significant greater increase in mindfulness in the intervention groups than in control groups (waiting-list or treatment as usual) in per-protocol analyses, and an increase in mindfulness (overall) was found to predict the effects of mindfulness-based interventions on levels of anxiety and depression [Citation6].

We found no effect modification by the baseline level of mindfulness (mean) of the effect of MBSR on the burden of somatic symptoms after 12 months, i.e. the effect of MBSR on somatic symptoms did not differ between participants with a high potential for increased mindfulness and those who already scored high on mindfulness before the intervention [Citation25]. With regard to mindfulness skills no effect of the MBSR-program was identified after 12 months in this trial. While this finding with regard to mindfulness skills might suggest that mindfulness is not the decisive ingredient it also might support the suggestion made by others that current mindfulness scales (including FFMQ) are less good predictors of symptom severity and quality of life among patients with anxiety and depression [Citation26,Citation27]. These authors have found that self-compassion related to both the theoretical and practical components of mindfulness-based interventions (including MBSR) is a better predictor of these outcomes.

One randomized controlled trial (N = 172) of the effect of the MBSR program extended by booster sessions (of support, sharing and practice) as compared with active control (nutrition intervention) or usual care showed statistically significantly longer term effects of MBSR on quality of life [Citation28]. This study also showed effects on other outcomes (e.g. coping) until 12 months after the intervention, while only anxiety (not significant at 12 months) and emotional control (significant at four months) were significantly improved after 24 months. These findings indicate a need for studies controlling for the effect of support and attention while evaluating the effect of home practice beyond the intervention period [Citation29].

In the above study [Citation28], levels of spiritual wellbeing were included in the reported general quality of life scores, which were statistically significantly better in the MBSR group after four months’ follow-up (compared with usual care) and after 12 months’ follow-up (compared with active control). In our trial, statistically significant between-group mean differences were found in spiritual wellbeing after six months’ follow-up, parallel to the effect observed on somatic symptom burden. We did not, however, find any effect modification of spiritual wellbeing when we analyzed the effect of MBSR on the burden of somatic symptoms after 12 months’ follow-up. We speculate that these six-month findings point to an effect of group support, rather than MBSR, on both the reported burden of somatic symptoms and levels of spiritual wellbeing.

The length of time after diagnosis at inclusion in our study might be a limitation, in that patients were at different stages of treatment; thus, although the results were adjusted for time since diagnosis, any effect of MBSR might have been modified by adjuvant treatment. Nevertheless, no effect modification was observed. Other potential limitations include lack of stratification of participants by baseline symptoms, the non-active control condition as well as the lack of valid data on mindfulness practice at home hindering analysis of the effect of amount of home training.

Conclusions

The trial is the first to evaluate the longer term effect of MBSR on the burden of breast cancer-related symptoms. We identified a statistically significantly effect of MBSR on the level of symptom burden immediately after the intervention and after six months’ follow-up and on distress throughout the 12-month follow-up. Our results indicate the need for further randomized controlled trials in which the effect of group support processes is controlled by comparing MBSR with an active control condition. In future trials, valid information should be collected on the degree of mindfulness practice, in order to determine adherence to and the effect of mindfulness practice during follow-up and to establish whether mindfulness is the active ingredient of MBSR among women with breast cancer.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to all the women who participated in the MICA trial and acknowledge the ‘mindfulness’ instructors Eva Broby Johansen (M.Sc. Psych) and Robert Jørgensen (M.Sc. Psych) for their skilled work with the participants. We also thank the staff of the participating clinical departments for their contributions to the conduct of the trial. Data manager Niels Christiansen and (Ph.D., M.Sc. Psych) Jacob Piet are acknowledged for important contributions. This work was funded by the Danish Cancer Society; the Psychosocial Research Committee (Grant number R13-A640-09-S3) and the CAM Research Committee (Grant number UP7001), University of Copenhagen; Multidisciplinary CAM- research (Grant number 603-44-204/SD), Danish Cancer Research Foundation (Grant number 50-08-2008) and the Danish Cancer Society Research Centre.

Declaration of interest: The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

References

- Ganz PA, Kwan L, Stanton AL, Bower JE, Belin TR. Physical and psychosocial recovery in the year after primary treatment of breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 2011;29:1101–9.

- Novack DH, Cameron O, Epel E, Ader R, Waldstein SR, Levenstein S, et al. Psychosomatic medicine: the scientific foundation of the biopsychosocial model. Acad Psychiatry 2007;31:388–401.

- Hunter MS, Coventry S, Hamed H, Fentiman I, Grunfeld EA. Evaluation of a group cognitive behavioural intervention for women suffering from menopausal symptoms following breast cancer treatment. Psychooncology 2009;18:560–3.

- Visser A, Garssen B, Vingerhoets A. Spirituality and well-being in cancer patients: A review. Psychooncology 2010;19: 565–72.

- Kabat-Zinn J, Chapman-Waldrop A. Compliance with an outpatient stress reduction program: Rates and predictors of program completion. J Behav Med 1988;11:333–52.

- Piet J, Würtzen H, Zachariae R. The effect of mindfulness-based therapy on symptoms of anxiety and depression in adult cancer patients and survivors: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Consult Clin Psychol 2012;80:1007–20.

- Bohlmeijer E, Prenger R, Taal E, Cuijpers P. The effects of mindfulness-based stress reduction therapy on mental health of adults with a chronic medical disease: A meta-analysis. J Psychosom Res 2010;68:539–44.

- Goyal M, Singh S, Sibinga EM, Gould NF, Rowland-Seymour A, Sharma R, et al. Meditation programs for psychological stress and well-being: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med 2014;174:357–68.

- Zainal NZ, Booth S, Huppert FA. The efficacy of mindfulness-based stress reduction on mental health of breast cancer patients: A meta-analysis. Psychooncology 2013;22:1457–65.

- Würtzen H, Dalton SO, Elsass P, Sumbundu AD, Steding-Jensen M, Karlsen RV, et al. Mindfulness significantly reduces self-reported levels of anxiety and depression: Results of a randomized controlled trial among 336 Danish women treated for stage I-III breast cancer. Eur J Cancer 2013;49:1365–73.

- Matousek RH, Dobkin PL. Weathering storms: A cohort study of how participation in a mindfulness-based stress reduction program benefits women after breast cancer treatment. Curr Oncol 2010;17:62–70.

- Lengacher CA, Reich RR, Post-White J, Moscoso M, Shelton MM, Barta M, et al. Mindfulness based stress reduction in post-treatment breast cancer patients: An examination of symptoms and symptom clusters. J Behav Med 2012;35:86–94.

- Würtzen H, Dalton SO, Andersen KK, Elsass P, Flyger HL, Sumbundu A, et al. Who participates in a randomized controlled trial of mindfulness based stress reduction (MBSR) after breast cancer? A study of factors associated with enrolment among Danish breast cancer patients. Psychooncology 2013;22:1180–5.

- Mouridsen HT, Bjerre KD, Christiansen P, Jensen MB, Moller S. Improvement of prognosis in breast cancer in Denmark 1977–2006, based on the nationwide reporting to the DBCG Registry. Acta Oncol 2008;47:525–36.

- Kabat-Zinn J. Full catastrophe living: Using the wisdom of your body and mind to face stress, pain and illness. London: Piatkus; 1990.

- Cella D, Land SR, Chang CH, Day R, Costantino JP, Wolmark N, et al. Symptom measurement in the Breast Cancer Prevention Trial (BCPT) (P-1): Psychometric properties of a new measure of symptoms for midlife women. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2008;109:515–26.

- Terhorst L, Blair-Belansky H, Moore PJ, Bender C. Evaluation of the psychometric properties of the BCPT Symptom Checklist with a sample of breast cancer patients before and after adjuvant therapy. Psychooncology 2011;20:961–8.

- Olsen LR, Mortensen EL, Bech P. The SCL-90 and SCL-90R versions validated by item response models in a Danish community sample. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2004;110:225–9.

- Baer RA, Smith GT, Lykins E, Button D, Krietemeyer J, Sauer S, et al. Construct validity of the five facet mindfulness questionnaire in meditating and nonmeditating samples. Assessment 2008;15:329–42.

- Jacobs TL, Epel ES, Lin J, Blackburn EH, Wolkowitz OM, Bridwell DA, et al. Intensive meditation training, immune cell telomerase activity, and psychological mediators. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2012;36:664–81.

- Peterman AH, Fitchett G, Brady MJ, Hernandez L, Cella D. Measuring spiritual well-being in people with cancer: The functional assessment of chronic illness therapy – Spiritual Well-being Scale (FACIT-Sp). Ann Behav Med 2002;24:49–58.

- Dolbeault S, Cayrou S, Bredart A, Viala AL, Desclaux B, Saltel P, et al. The effectiveness of a psycho-educational group after early-stage breast cancer treatment: Results of a randomized French study. Psychooncology 2009;18:647–56.

- Shao J, Zhong B. Last observation carry-forward and last observation analysis. Stat Med 2003;22:2429–41.

- Hofmann SG, Sawyer AT, Witt AA, Oh D. The effect of mindfulness-based therapy on anxiety and depression: A meta-analytic review. J Consult Clin Psychol 2010;78:169–83.

- Jacobsen PB, Jim HS. Psychosocial interventions for anxiety and depression in adult cancer patients: Achievements and challenges. CA Cancer J Clin 2008;58:214–30.

- Shapiro SL, Brown KW, Thoresen C, Plante TG. The moderation of mindfulness-based stress reduction effects by trait mindfulness: Results from a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Psychol 2011;67:267–77.

- Van Dam NT, Hobkirk AL, Danoff-Burg S, Earleywine M. Mind your words: Positive and negative items create method effects on the five facet mindfulness questionnaire. Assessment 2012;19:198–204.

- Van Dam NT, Sheppard SC, Forsyth JP, Earleywine M. Self-compassion is a better predictor than mindfulness of symptom severity and quality of life in mixed anxiety and depression. J Anxiety Disord 2011;25:123–30.

- Henderson VP, Clemow L, Massion AO, Hurley TG, Druker S, Hebert JR. The effects of mindfulness-based stress reduction on psychosocial outcomes and quality of life in early-stage breast cancer patients: A randomized trial. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2012;131:99–109.

- Floyd A, Moyer A. Group vs. individual exercise interventions for women with breast cancer: A meta-analysis. Health Psychol Rev 2009;4:22–41.