Abstract

Purpose. Before, during and after autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HD-ASCT) patients suffer from significant loss of physical function, and experience multiple complications during and after hospitalization. Studies regarding safety and feasibility of physical exercise interventions for patients undergoing treatment with HD-ASCT are missing.

Methods. Forty patients referred to HD-ASCT treatment, suffering from multiple myeloma, lymphoma or amyloidosis aged 23–70 years were enrolled in a prospective longitudinal study. The study consisted of a home-based exercise program for use in the ambulatory setting and supervised exercise sessions Monday to Friday for 30–40 minutes during admission. Safety of the exercise program and physical tests were assessed by using a weekly questionnaire and report of inadvertent incidences. Adherence to the home-based exercise program was reported by using a patient diary, weekly questionnaire and count of daily attendance in supervised sessions during hospital stay. Data collection was scheduled shortly after diagnosis, admission, discharge and eight weeks after discharge. Success criteria were: no severe adverse events in relation to exercise program and assessments; performance of three days of physical exercises during ambulatory period and hospital stay and 150 minutes of weekly physical activity.

Results. Of the 25 patients who completed the exercise program during the ambulatory period prior to HD-ASCT a mean weekly attendance to home exercises of 5.3 (± 2.8) days and a median weekly physical activity of 240 (± 153.8) minutes was found. During hospital stay the median attendance was 9 (± 3.9) days of 10 (± 6.9) possible. Two months after discharge the patients reported a median weekly physical activity of 360 (2745.5) minutes. No severe adverse events in relation to the exercise program or assessments were reported.

Conclusion. Based on the enrolled number of patients the physical exercise intervention for patients undergoing HD-ASCT seems promising regarding feasibility and safety.

High-dose chemotherapy and autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HD-ASCT) is a treatment of malignant hematological diseases, such as lymphoma, multiple myeloma and amyloidosis. Prior to the HD-ASCT the patients receive initial treatment for 10–12 weeks in an ambulatory setting. The treatment trajectory varies widely depending on disease, individual and dose response. Infections, pain, oral mucositis, nausea and diarrhea are common side effects during the procedure. Along with loss of physical function the complications and side effects of the therapeutic treatment present a severe burden that may limit rehabilitation to daily life and return to work.

It has been shown, that physical activity amongst Non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) patients declines after being diagnosed and that the patients have difficulty in regaining their habitual levels of physical activity after treatment [Citation1]. Courneya et al. investigated the levels of physical activity amongst 88 multiple myeloma patients and found that only 6.8% of the patients during treatment and 20.4% after treatment met the physical activity recommendations from American College of Sports Medicine [Citation2]. Several physical exercise intervention studies with cancer patients show a positive effect on aerobic capacity, strength, body composition, physical function, emotions, immune system, fatigue and health-related quality of life [Citation3–10]. Studies suggest that physical exercise should be introduced as early as possible after diagnosis [Citation1,Citation11].

Multimodal fast-track recovery programs have been implemented with great success in the fields of surgery. The concept aims to improve patient trajectories by optimization of patient information, logistics, pain treatment, and postoperative physical rehabilitation [Citation12]. This multidisciplinary action including physicians, nurses, physiotherapists and dieticians provide a faster rehabilitation of patients following a surgical procedure, improve the quality of treatment, shorten the admission period and reduce costs of hospital stay [Citation12].

The aim of this study was to investigate whether an exercise intervention, as part of a fast-track trajectory, before, during and after HD-ASCT, was feasible and safe for patients. Further, to investigate whether the patients were able to comply and adhere to the exercise intervention.

Material and methods

Recruitment of participants

The study was a single-center prospective longitudinal feasibility study with consecutive inclusion of patients diagnosed with different types of lymphoma, relapse of lymphoma, multiple myeloma or amyloidosis undergoing treatment with high-dose chemotherapy and autologous stem cell transplantation. Patients were referred to the University Hospital of Copenhagen, Rigshospitalet (UCR), from the Capital Region, southern parts of Zealand, Lolland, Falster, Bornholm, the Faroe Islands, and Greenland. The physical exercise intervention was part of a new treatment regimen for patients undergoing HD-ASCT at UCR. Therefore patients did not sign an informed consent and ethical approval was not obtained.

Patients were enrolled by hematologists at the UCR from June 2013 to July 2014. Before participation in the exercise intervention and physical tests, the patients were screened for osteolytic foci or other precautions by the consulting hematologist, who informed the patient about the optimized patient-trajectory for patients undergoing HD-ASCT.

Criteria for inclusion: age ≥ 18 years; diagnosis of different types of lymphoma, relapse of lymphoma, multiple myeloma or amyloidosis and referral to HD-ASCT.

Patients were excluded from the study upon refusal to participate in the physical exercise intervention or if HD-ASCT was cancelled due to progression of disease or other severe co-morbidity.

Osteolytic foci were not exclusion criteria. Exercises were individually tailored and exercises and tests straining fragile bone were omitted.

Demographic data, physical activity levels and anthropometric data were collected at each test session.

Baseline assessment and follow-up

Data collection was scheduled at baseline shortly after diagnosis, admission, discharge and eight weeks after discharge.

Data analyses

Sample size

The study is ongoing. Preliminary results regarding 25 patients are reported.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics was used to demonstrate feasibility and safety. Number of adverse events related to physical exercises, days of physical exercise performed before, during and two months after HD-ASCT treatment were recorded as well as median weekly performed minutes of physical activity. Socio-demographic and clinical characteristics was attained through the patient's medical journal.

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 19.0.

Primary endpoints

Feasibility

Adherence to the intervention was assessed by a patient reported exercise diary issued to the patients at test session 1 and weekly telephone calls from a physiotherapist. The patients were asked to fill in an exercise diary during the weeks of initial outpatient treatment (Supplementary Table I, to be found online at http://informahealthcare.com/doi/abs/10.3109/0284186X.2014.999872). The participants were instructed to mark the performed type of exercise and fill in minutes spent, perceived rate of exertion, number of intervals, repetitions and sets. If the diaries were not handed in, the patients were contacted by phone and asked the same questions concerning exercises performed the last week.

During hospital stay, attendance to supervised sessions was recorded by a physiotherapist (Supplementary Table II, to be found online at http://informahealthcare.com/doi/abs/10.3109/0284186X.2014.999872). Performance of three days per week of physical exercises during the ambulatory period and hospital stay and 150 minutes of weekly physical activity at moderate intensity before, during and after treatment was considered to be a success. Attrition was assessed by the number/percentage of patients who dropped out of the study and the reasons for dropping out.

Safety.

Another success criterion was no severe adverse events in relation to the exercise program and assessments such as heart failure, bone fractures and bleeding.

Prior to assessment 1, the patients were scored by the physician in relation to osteolytic lesions or foci verified by whole body x-ray and clinical signs. If needed, the physician ordered a positron emission tomography-computed tomography (PET-CT) scan or CT-scan for further screening. The patient's bone status was scored by the physician ().

Table I. Risk of fractures scoring system.

Patients with osteolytic foci or bone metastasis exercised with reduced intensity and followed a specific exercise program with exercises designed for osteopenic patients. Patients were instructed to discontinue the exercise session and contact the physiotherapist in case of acute pain related to exercises.

Contraindications for physical testing or participa-ting in an exercise session were platelet count < 15 × 109/l, hemoglobin < 5.0 mmol/l and systolic blood pressure < 95 mmHg. Fever was only a contraindication if the patient was affected in a general way.

The patients and staff were instructed to report any adverse events such as petechiae, hemorrhage, breast pain, musculoskeletal soreness or direct pain related to the exercise program (Supplementary Table III, to be found online at http://informahealthcare.com/doi/abs/10.3109/0284186X.2014.999872).

Exercise intervention and physical assessment

Ambulatory period

One to two weeks after diagnosis, the patients were instructed in a self-training program covering strength- and cardiovascular exercise for use in the outpatient setting. They received an exercise diary to fill in and hand back at weekly outpatient controls.

We constructed two different exercise programs for the intervention; one regular exercise program for patients without osteolytic foci or bone metastasis. Patients without bone malignancy or osteolytic foci were instructed to perform aerobic exercise at Borg RPE 12–18 and strength training exercises at 6–12 RM.

Patients at risk of fracture were instructed in an exercise program fit for osteopenic patients, and were instructed to perform aerobic exercise at Borg RPE 12–16 and strength training exercises at 18–25 RM. Patients were instructed to progress their aerobic exercise program with interval training.

Strength exercises were consistently used throughout the trajectory, six exercises for upper- and lower extremities and the core. Each exercise had four variables allowing the exercise to progress or regress depending on the daily status of the patient.

In the ambulatory setting the aerobic exercise was individually matched to the participants’ capabilities and possibilities at home or in the surroundings, e.g. walking, Nordic walking, jogging or bicycling. Warm-up and cool-down periods were 5–10 minutes of light aerobic exercise, e.g. bicycling (Borg RPE 10).

The patients received a telephone number to the physiotherapist in case of questions.

Hospital stay

Monday to Friday during admission the patients participated in supervised group exercise or they were supervised individually for 30–45 minutes. The nurses screened the patients’ blood tests and vital values every morning before the patients were allowed to participate in the exercise program and if necessary, the patients received blood transfusions.

During admission aerobic exercise consisted mostly of bicycling on regular fitness bike or in cases of patients being bed-ridden by the use of bed-bike. The intervention consisted of cardiovascular exercise three days a week. Karvonen's formulae was used [max pulse (HRmax): 208–(0.7 × age)] and target rate was estimated by [(HRmax–HRrest)×% intensity]+ HRrest. Starting at 50% and increasing up to 80%. Strength training exercises twice a week.

Warm-up and cool-down periods were 5–10 minutes of light aerobic exercise, e.g. bicycling (Borg RPE 10).

Besides the group exercise session physical activity during the rest of the day were facilitated with an increased focus on basic mobility administered by nurses. The aim was to keep the patient out of bed 4–8 hours daily.

Physical assessments

| 1) | The six-minute walk test (SMWT) from the American Thoracic Society was used to measure aerobic capacity [Citation13]. Perceived rate of exertion was noted shortly upon completion of the test. | ||||

| 2) | Maximal isometric voluntary contraction was measured with a handheld dynamometer for knee extensors bilaterally (PowerTrackIITM Commander, JTECH Medical, Salt Lake City, USA). Test positions were standardized and rigorously tested prior to the intervention by two physiotherapists. The patients were instructed to recruit maximal voluntary contraction for five seconds at a time. Each leg was tested four times with a one minute interval in between trials. The highest score on each leg was registered. | ||||

| 3) | 30 seconds Sit To Stand test (STS) for lower body strength. | ||||

| 4) | Aastrand-Rhyming cycle ergometer test for changes in aerobic capacity over time. | ||||

Results

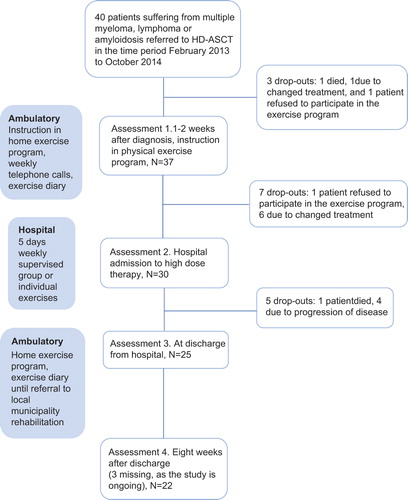

Of the 40 patients enrolled in the study, one refused to participate in the exercise intervention, one patient died and one patient was withdrawn due to changed treatment before entering the study. After the first assessment, 10 patients were withdrawn because of change in treatment and disease progression, one patient died and one patient refused to participate in the exercise intervention. In all 25 patients participated in the exercise intervention and 22 have completed all four test sessions ().

Socio-demographic and clinical characteristics of the 25 patients completing the treatment trajectory are shown in .

Table II. Socio-demographic and clinical characteristics of the HD-ASCT study population.

Preliminary results of the 25 patients who completed the home-based exercise program prior to HD-ASCT and the supervised exercise sessions during hospital stay, showed a mean weekly attendance to home exercises of 5.3 (± 2.8) days and a median weekly physical activity of 240 (± 153.8) minutes during the ambulatory period (). Only 10 of the 25 patients completing the ambulatory period prior to HD-ASCT handed in an exercise diary. The other 15 patients answered questions regarding adherence to exercise program by weekly telephone calls from the physiotherapist. Four patients performed less than the prescribed 150 minutes of physical activity per week during the ambulatory setting. One patient performed 30 minutes of physical activity per week, one patient performed 75 minutes and 2 patients 90 minutes. All 25 patients reported that they performed aerobic exercises with a median Borg RPE scale ranging between 10 and 16 during the ambulatory period. Only 11 patients reported that they performed the strength training program.

Table III. Patient reported performed physical exercises during the ambulatory treatment period, during admission and 2 months after discharge.

During hospital stay the median attendance was 9 (± 3.9) days of 10 (± 6.9) possible. All patients attended both the aerobic and the strength training supervised sessions. Eight patients had to have individual supervised sessions, due to infections. Two months after discharge, the median patient reported physical activity was 360 (2745.5) minutes per week.

Of the 22 patients completing all exercise periods, one patient developed hematoma in the groin in relation to aerobic training and two patients complained about muscle soreness, but none discontinued the exercise program due to this (). No other adverse events in relation to the exercise program or physical assessments were reported or registered.

The SMWT could not be used in assessment 1 in relation to a patient who had hip-pain ().

Table IV. Performed physical assessments, adverse events related to assessments and reasons for missing assessments.

The isometric strength test was omitted 22 times due to risk of bone fracture and twice due to hip pain and low-back pain.

Two patients could not carry out the 30 seconds STS assessment due to hip pain and low-back pain.

The Aastrand Rhyming test was omitted nine times due to low pulse or low aerobic capacity and once by a patient suffering from low-back pain.

Discussion

As other studies show that patients diagnosed with lymphoma and multiple myeloma experience a decline in their physical performance, one of the aims of the optimized patient trajectory was to intercept the patients before decline in physical function [Citation1,Citation2].

Only two (5%) of the 40 patients, were not interested in participating in the exercise program.

Our criteria of success, was a performance of exercises three days per week and a mean of 150 minutes of physical activity per week. Of the 25 patients who completed the ambulatory exercise program prior to HD-ASCT, a mean of 5.28 days of weekly exercises and a median of 240 minutes of physical activity per week were performed. Two months after discharge, the reported performance of weekly physical activity exceeded the period prior to HD-ASCT.

We therefore consider the results of attrition and adherence in this study to be promising compared to other studies that have shown low compliance to home-based exercise programs [Citation14].

Some patients had 11 weeks of ambulatory treatment prior to HD-ASCT and for some of these patients it might have been difficult to maintain motivation for continuous physical activity. We believe that the interdisciplinary approach has been crucial in order to secure the high level of adherence to the exercise intervention. The early intervention with the physician initially informing the patient about the exercise intervention may be important. A study of 450 cancer survivors showed that a simple recommendation from the physician to exercise resulted in significant increases in physical activity [Citation15]. The test-session with the physiotherapist may further have induced motivation and goal setting for the individual in order to maintain physical function and performance. Finally, the exercise diary and weekly telephone calls from the physiotherapists may also have contributed to the high adherence to the exercise program as shown in other studies [Citation16].

However, the adherence to strength training exercises during the ambulatory period was low. Only 11 of the 25 patients performed the prescribed strength training exercises. One could argue that the strength training exercises were too onerous. Although only six exercises were introduced, it may have been easier to go for a walk or bicycle ride, which in this study was the preferred physical activity.

The study has some weaknesses. The total physical activity registered during admission has not yet been analyzed. This makes it difficult to compare the time spent on physical activity during admission with the out-patient period. However, attendance to supervised exercise sessions during admission was higher than the expected three days per week. Furthermore, the physical activity and exercises performed during the out-patient periods relied on self-reported data, and could have led to recall/information bias.

When we first designed this study the idea was to implement progression of patients` exercise intensity both during the out-patient and the in-patient periods. However, it was difficult to administer the progression of exercises during the out-patient period. It might in future studies be a good idea to see the patient during the out-patient period to secure the progression. During the in-patient period the exercise sessions and intensity of aerobic exercise were adjusted daily according to the wellbeing of the patient. Progression of patients’ exercise performance was to some extent affected by nausea, as the intensity had to be lowered.

One could argue that the choice of physical assessments was too strenuous. Several patients were unable to bike at the required 50 watt and some had too low pulse. In future studies, it might be sufficient to use the SMWT where compliance was high.

The isometric strength test was not a good choice for patients suffering from malignancy in the spine or at risk of bone fractures in the proximal parts of femur. Instead the 30 seconds STS test might be sufficient to give an assessment of lower body strength. Only a few patients did not comply with the 30 seconds STS test.

Multiple myeloma reduces bone mineral density over time with the risk of pathological fractures, and most exercise studies exclude patients due to this. However, in this study including patients with ostelytic foci and bone metastasis, we encountered no bone fractures or osseous pain associated with the exercise interventions.

We do not know, if the implications of muscle soreness or other not reported incidences experienced by patients during the out-patient period, may have had an influence on the exercise intensity and number of days exercised. One patient, who had had excision of a lipoma in the groin, developed a hematoma after performing the exercise program. However the patient continued the exercise program without further incidences.

The group exercise sessions during hospital stay varied regarding number of participants on a daily basis from one to five. The patients’ capability to exercise, and the length of exercise sessions varied from patient to patient mainly depending on the treatment-associated side effects. The individual difference in physical performance at group exercise sessions did not seem to represent a barrier for the flow and dynamics of the group. The patients seemed to benefit socially from the exercise sessions, and were able to share their experiences with fellow HD-ASCT patients and were supportive to each other. If patients were unable to attend the group exercise sessions, it did not affect their adherence to the phy-sical exercise intervention. They exercised individually supervised by a physiotherapist and the nurses and physicians supported the patient in additional exercise, mobilization or use of bed-bike.

In summary, a physical exercise intervention as part of a fast-track trajectory as known from the surgery arena seems applicable in the medical field and may therefore show the same benefits regarding duration of hospital stay, complications and physical function thus facilitating patients return to daily life.

Data concerning physical function and patient motivation will be presented in a future article.

Acknowledgments

The current project was financially supported by The Capital Region of Denmark and Roche pharmaceuticals. The authors report no conflicts of interest. All the authors are responsible for the content and writing of the article.

Supplementary material available online

Supplementary Tables I–III, to be found online at http://informahealthcare.com/doi/abs/10.3109/0284186X.2014.999872.

ionc_a_999872_sm6569.pdf

Download PDF (91.7 KB)Declaration of interest: The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

References

- Vallance JKH, Courneya KS, Jones LW. Differences in quality of life between non-Hodgkin's lymphoma survivors meeting and not meeting public health exercise guidelines. Psychooncology 2005;14:979–91.

- Jones LW, Courneya KS, Vallance JKH. Association between exercise and quality of life in multiple myeloma cancer survivors. Support Care Cancer 2004;12:780–8.

- Dimeo F, Fetscher S, Lange W, Mertelsmann R, Keul J. Effects of aerobic exercise on the physical performance and incidence of treatment-related complications after high-dose chemotherapy. Blood 1997;90:3390–4.

- Jarden M, Baadsgaard MT, Hovgaard DJ. A randomized trial on the effect of a multimodal intervention on physical capacity, functional performance and quality of life in adult patients undergoing allogeneic SCT. Bone Marrow Transplant 2009;43:725–37.

- Baumann FT, Zopf EM, Nykamp E, Krauet L, Schüle K, Elter T, et al. Physical activity for patients undergoing an allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: Benefits of a moderate exercise intervention. Eur J Haematol 2011;87:14.

- Wiskemann J, Dreger P, Schwerdtfeger R, Bondong A, Huber G, Kleindienst N, et al. Effects of a partly self-administered exercise program before, during, and after allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Blood 2010;117:26042613.

- Knols RH, de Bruin ED, Uebelhart D, Aufdemkampe G, Schanz U, Stenner-liewen F, et al. Effects of an outpatient physical exercise program on hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation recipients: A randomized clinical trial. Bone Marrow Transplant 2011;46:1245–55.

- Courneya KS, Sellar CM, Stevinson C, McNeely ML, Peddle CJ, Friedenreich CM, et al. Randomized controlled trial of the effects of aerobic exercise on physical functioning and quality of life in lymphoma patients. J Clin Oncol 2009;27:4605–12.

- Hayes S, Davies PSW, Parker T, Bashford J, Newman B. Quality of life changes following peripheral blood stem cell transplantation and participation in a mixed-type, moderate-intensity, exercise program. Bone Marrow Transplant 2004;33:553–8.

- Adamsen L, Quist M, Andersen C, Møller T, Herrstedt J, Kronborg D, et al. Effect of a multimodal high intensity exercise intervention in cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy: Randomised controlled trial. Br Med J 2009; 13:339:b3410.

- Wiskemann J, Huber G. Physical exercise as adjuvant therapy for patients undergoing hematopoetic stem cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant 2008;41:321–9.

- Holm B, Kristensen MT, Husted H, Kehlet H, Bandholm T. Thigh and knee circumference, knee-extension strength, and functional performance after fast-track total hip arthroplasty. PM & R 2011;3:117–24.

- American Thoracic Society. ATS statement: Guidelines for the six-minute walk test. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2002;166:111–7.

- Quist M, Rørth M, Langer S, Jones LW, Laursen JH, Pappot H, et al. Safety and feasibility of a combined exercise intervention for inoperable lung cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy: A pilot study. Lung Cancer 2012;75: 203–8.

- Jones LW, Courneya KS, Fairey AS, Mackey JR. Effects of an oncologist's recommendation to exercise on self-reported exercise behavior in newly diagnosed breast cancer survivors: A single-blind, randomized controlled trial. Ann Behav Med 2004;28:105–13.

- Rock CL, Doyle C, Demark-Wahnefried W, Meyerhardt J, Courneya KS, Schwartz AL et al. Nutrition and physical activity guidelines for cancer survivors. CA Cancer J Clin 2012;62:242–74.