Abstract

Purpose. To test the hypothesis that head and neck cancer (HNC) patients are in need of specialized follow-up (FU). This was done by an evaluation of the FU activities in a cohort of patients followed longitudinally for five years with focus on optimal duration and interval of post-therapeutic follow-up.

Methods. The study evaluated a cohort consisting of 197 consecutive patients with HNC treated at Aarhus University Hospital from 1 January to 31 December 2009. The inclusion criteria was that patients should be deemed free of disease two months after completed primary curative intended treatment or after primary curative salvage. It left 141 patients available for analysis. Data were collected through a medical chart review and from the Danish Head and Neck Cancer Group (DAHANCA) database. Parameters recorded were: regular or extraordinary visit, alarm symptoms, late morbidity and the consequences of these.

Results. The 141 patients underwent 1408 FU visits. Only 15 of the 141 patients had no tumor problems or morbidity issues raised at any FU visit. Suspicion of recurrent disease was observed at 207 of the 1408 FU visits, involving 97 patients and resulted in a total of 370 diagnostic procedures; 170 (82%) visits with suspicion of recurrence occurred within 3½ years after end of treatment. A recurrence was verified in 30 patients. Additionally four new primary head and neck cancer was diagnosed during follow-up. There were 1150 visits (82%) involving 135 patients in which late treatment-related morbidity was recorded. Actions taken related to morbidity happened in 71 patients, but no new problems appeared after three years.

Conclusion. The study document the need of specialized FU, as 86% of all HNC survivors have tumor or severe morbidity issues during FU. The data suggest that 3½-year FU after ended therapy may be sufficient for the majority of patients.

Danish head and neck cancer (HNC) patients are offered a five-year follow-up (FU) program according to the DAHANCA guidelines (www.dahanca.dk). This strategy was partly tailored to enable early detection of recurrent disease, as more than 80% of all recurrences appear within three years after treatment [Citation1], and with the underlying assumption that early detection provides a better chance of a cure. Despite the lack of evidence towards this practice, both regarding detection of recurrences and diagnosing new primary tumors, many patients are enrolled in FU programs at potentially high costs each year [Citation2,Citation3]. Follow-up strategies in HNC differ worldwide in the recommended frequency of FU visits and duration of the FU, but no strategy has been proven superior to detect recurrence of disease or new primary tumors [Citation2,Citation3]. Other significant reasons for scheduled FU are evaluation of treatment response, monitoring and management of complications, optimization of rehabilitation, promotion of smoking and excessive alcohol cessation, provision of support, counseling and patient education.

We hypothesize that curatively treated HNC patients benefits from scheduled FU visits as this strategy detects recurrences timely for successful salvage. Furthermore, HNC patients are in need of continued management of morbidity which is handled at the same occasion. To test this hypothesis we evaluated the FU activities performed in a cohort of patients with HNC longitudinally followed for five years. The aim was to identify the optimal duration and frequency of post-therapeutic follow-up. To our knowledge no other study has, approached this topic considering all problems in a longitudinal manner.

Methods

The study evaluated a cohort of 197 consecutive new patients with carcinoma of the head and neck treated at Aarhus University Hospital between 1 January and 31 December 2009. Included patients should be deemed free of disease two months after ended primary curative intended treatment or after primary curative salvage. This left 141 patients eligible for this study (Supplementary Figure 1, to be found online at http://informahealthcare.com/doi/abs/10.3109/0284186X.2015.1028591). The patients’ first FU visit after the two months post-treatment evaluation was included in the analysis. For the majority of patients this took place approximately five months after finalized treatment whereas a few patients had their visit brought forward due to symptoms. At each FU all patients underwent a full clinical examination of the head and neck.

Data were extracted from medical records and recorded in the DAHANCA database. This database contains a wide range of prospectively recorded information regarding patient and tumor characteristics, treatment and outcome. We added supplementary information concerning the FU visits: Was it a regular or extraordinary visit?; Did the patient/physician report any acknowledged alarm symptoms or signs of recurrence ()?; Did the patient suffer from late treatment-related morbidity, and if so what type of morbidity and degree of severity (www.dahanca.dk) [Citation5]? Finally, we recorded further diagnostic work-up initiated on suspicion of recurrent disease or late morbidity, and the type of management/referrals performed.

Table I. Patient and visit characteristics.

Statistical analysis was mainly of descriptive character. The outcome of the consultations were illustrated by Kaplan-Meier failure curves for potential explanatory variables. In addition, potential explanatory variables were expressed by odd ratios (OR). The following variables were included in the analysis: Alarm symptoms, primary treatment, primary tumor site and type of FU visit in terms of scheduled or acute visits. Outcome of consultations were calculated from the date of ended primary treatment until the date of first recurrence or suspicion of recurrence, time of first referral to management of morbidity or first registration of moderate to severe morbidity.

All analysis was performed by STATA 12 software package. The Regional Ethics Committee concluded that the study was a quality assurance project, and as such did not need formal approval.

Results

shows the 141 patients characteristics and the recoded alarm symptoms at 1408 FU visits and their association with recurrences. The median follow-up period was 4.8 years (0.4–5.6) calculated from the end of treatment. Most follow-up visits were according to schedule (n = 1218), or doctor (n = 32) or patient requested (n = 84). The remainder were in response to diagnostic work-up (n = 74). Median FU frequency was 4 (range 1–10) in the first year, 3 (1–7) in the second year, 2 (1–8) in the third year, 2 (1–5) in the fourth year and 1 (1–4) in the fifth year. Overall the median number of visits per patient was 11 (1–19). Additional 434 extra visits were performed outside the FU clinic for diagnostic procedures. These visits were not included in the analysis.

Recurrence of disease

Alarm symptoms and signs of recurrent disease were recorded at 285 visits (, , Supplementary Figure 3A, available online at to be found online at http://informahealthcare.com/doi/abs/10.3109/0284186X.2015.1028591). In 177 FU visits the alarm symptoms consisted of subjective symptoms alone; and in 58 FU visits they were combined with objective signs. Signs alone occurred at 50 FU visits. In 73% (207/285) of the FU visits involving 94 patients (and occurring from 1 to 11 times), the doctor raised a suspicion of recurrence. The rate of FU visit with doctor's suspicion of recurrent disease was 15% (207/1408). Suspicion was most commonly seen in cancer of the pharynx (n = 34) followed by larynx (n = 22) and oral cavity (n = 21). Most FU visits which gave rise to suspicion of recurrent disease, 64% (n = 132) happened on regular follow-up and 25% (n = 53) were extra visits brought forward by the patients. If patients were symptomatic 35% requested an acute visit. The risk of being suspected of recurrence was higher when the FU visit was brought forward by the patient [OR 12.9 (95% CI 8.1–20.9)] compared with scheduled FU visits. Likewise, the risk of being suspected of recurrence was significantly higher if the alarm symptom was pain [OR 22.7 (95% CI 15.1–33.9)].

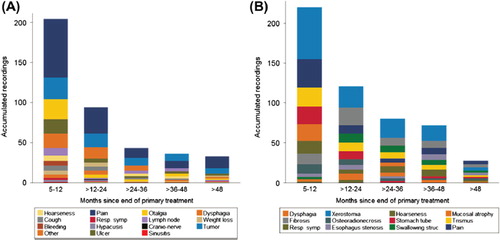

Figure 1. Recordings of the frequency of alarm symptoms (A) and the frequency of all the recordings of moderate-severe morbidity (B) during the five-year FU. Most recordings took place in the early FU.

A recurrence was verified in 30 patients, and the risk of a true recurrence was significantly related to pain as a presenting symptom [OR 11.4 (95% CI 5.4–23.8)]. Five (17%) were asymptomatic. A total of 370 procedures were performed to verify or dismiss the suspicion. The median number of procedures (per patient) performed was 2 (1–21). As shown in most procedures and verifications happened within 31/2-year after completed treatment. The median time from suspicion to verification or dismission was 14 (3–106) and 15 (0–131) days, respectively. The pattern of failure of was in T site (n = 16), N-site (n = 4), M site (n = 8), T and N site (n = 1), N and M site (n = 1), respectively. The most common site of recurrence was pharynx (n = 17) followed by the oral cavity (n = 8). In fact, the hazard ratio for getting a recurrence was much higher for patients with pharynx carcinoma when compared with other tumor sites [OR 3.4 (95% CI 1.6–7.1)].

Figure 2A. Shows the accumulated FU visits during the five-year FU. The distribution of the 285 consultations with alarm symptoms, the 207 visits in which suspicion of recurrent disease, the distribution of the 370 diagnostic procedures and the 169 referrals conducted during FU in regard to management of morbidity. hows “time to first recording” of suspicion of recurrent disease, referral to management of morbidity and registration of moderate to severe morbidity. It illustrates that only few new problems occurred after 3½ years of FU.

Distant metastases were mostly diagnosed in other departments (6/9). Salvage treatment with curative intent was offered to 16 patients and was successful in 7. Overall 28 patients have died and 18 of them of the primary HNC.

A total of 23 new primary tumors were recorded, but only four were in the head and neck area (1 oral cavity, 2 larynx and 1 pharynx). Only two of the latter were identified in the FU clinic; the remaining 21 tumors were diagnosed in other departments.

Morbidity

Data regarding late morbidity and management are listed in and Supplementary Table I (to be found online at http://informahealthcare.com/doi/abs/10.3109/0284186X.2015.1028591). Totally 4262 recordings of any morbidity were conducted. A total of 135 (96%) of the patients were diagnosed with any late treatment-related morbidity. The management of morbidity largely consisted of medical prescription or referrals to an otolaryngologist or maxillofacial surgeon. Such action occurred at 10% of all FU visits (n = 144/1408) (Supplementary Table I to be found online at http://informahealthcare.com/doi/abs/10.3109/0284186X.2015.1028591). Instructions about the importance of smoking cessation [Citation8,Citation9] were equally distributed throughout the FU course. Smokers or former smokers constituted 121 (86%) of all included patients. Of the smokers, 45 had stopped before the diagnosis of cancer and 24 at the time of diagnosis or during FU, but 52 patients continued smoking despite advice of cessation.

Table II. Any recordings of morbidity and the distribution between the different treatment modalities.

Supplementary Figures 2 and 3B (to be found online at http://informahealthcare.com/doi/abs/10.3109/0284186X.2015.1028591) show that moderate to severe morbidity was observed in 335 visits involving 68 patients. About half had sustaining symptoms throughout the five years. They had all (except one) received radiotherapy (RT) as a part of their primary treatment. Among those treated with surgery alone the main problems was speech and eating trouble due to decreased mobility of the tongue. A minor part suffered from tissue defects and aspiration tendency due to velopalatal insufficiency.

Referrals for further management of morbidity were assigned to 71 patients (1–10 referrals per patient). shows that after 3½ year post-treatment only one patient developed a new recording of moderate to severe morbidity. The hazard ratio of recordings of moderate-severe morbidity was significantly increased if the patients had RT as part of their treatment [OR 5.8 (95% CI 2.8–9.2)]. Furthermore, it shows that no new patients had a first time referral for management of morbidity after that same time point. Supplementary Figure 4 (to be found online at http://informahealthcare.com/doi/abs/10.3109/0284186X.2015.1028591) shows all distribution over time of all interventions towards either tumor or morbidity problems. Interventions were prescribed in 373 visits. The distribution of these visits ranged between 17% and 31% each year. In the fifth year, only four patients (at 5 visits) had management towards previously detected morbidity corresponding to 3% of all patients.

Only 15 (11%) patients completed all FU visits with no tumor problems or morbidity issues raised at any time. Further five (4%) patients had no problems, but did not complete FU due to death of other causes.

Discussion

The study was undertaken to evaluate the structure and timing of the current FU practice in HNC patients. Two groups [Citation2,Citation3] have recently reviewed the literature regarding optimal duration and interval of post-therapeutic FU, and both concluded, that specialist FU should be maintained with frequent visits in the first two years and thereafter with declining frequency. However, they both acknowledged that only low level of evidence exists. Boysen et al. [Citation10] made the assertion that follow-up clinic appointments could be cut “by a modest estimate of one-third” with no negative consequences for patient outcome. This is in tune with our results where only very few new patients presented problems after 3½ years of FU.

It appears that there is very little survival benefit of FU [Citation5,Citation6,Citation10–14]. Despite this, most authors stated that the five-year FU period cannot be reduced due to the high risk of developing new primaries, management of late treatment-related morbidity as well as psychosocial tasks [Citation5,Citation6,Citation15–17]. In the present study we found that only very few new primary tumors were detected in the FU clinic, and that no patients were offered management of new morbidity after the completed 3½ years. A risk assessment before terminating the ordinary FU will identify the group of patients who need continued management of existing morbidity. In our cohort, only four patients (3%) had management of previously detected morbidity in the fifth year of follow up. This corresponds well with the 2% seen in our former study [Citation4]. We did not record guidance of patients in relation to morbidity, as the medical charts were incomplete in this regard. However, in our former study we observed that 49% of the patients received guidance for existing morbidity, and that this happened both early or late in the FU [Citation4].

Our study confirmed the hypothesis that head and neck cancer patients are in need of specialized follow-up. This supports the current and planned strategy of DAHANCA (www.DAHANCA.dk) with a higher frequency of FU visits in the first two years followed with a decreasing frequency in the following years as the risk of recurrence is declining, as are the visits with symptomatic patients. Only few patients were suspected of recurrence of disease late in the FU, and only two patients had proven late recurrences (4.5 and 5 years after ended primary treatment). For patients with alarm symptoms of recurrent disease it is important to have a quick access to medical attention. In order to ensure an adequate patient awareness of the symptoms should patient education be incorporated into the FU program. In a recent evaluation of the Danish HNC FU program among 619 patients we found that appearance of new symptoms between visits generally did not result in the patient requesting an earlier visit, indicating the necessity of patient education [Citation4]. Furthermore our present study also indicate that patients are reluctant in bringing the FU visit forward, as only 35% of symptomatic patients did that. Focus should be placed on appearance of pain, lump/tumor, ulcer, weight loss and enlarged lymph nodes. Pain was the most frequent alarm symptom among the verified recurrences (53%). In order to increase patient awareness of these alarm symptoms, we believe implementation of a self-reporting system, as for an example, a questionnaire on “patient reported outcome measures”, could be useful (PROM) [Citation18]. However, any changes to the current structure of scheduled visits are best evaluated in a randomized trial design.

Conclusion

Our data support the usefulness of specialized FU, as 86% of all HNC survivors have tumor or moderate to severe morbidity issues during FU. For the majority of patients it was sufficient with a 3½ year FU after completed therapy. After that time resources should be allocated for individualized FU for those patients, who continue to have severe problems.

Supplementary material available online

Supplementary Figures 1–4 and Table I available online at to be found online at http://informahealthcare.com/doi/abs/10.3109/0284186X.2015.1028591

ionc_a_1028591_sm7151.pdf

Download PDF (867.5 KB)Acknowledgments

Supported by: CIRRO – The Lundbeck Foundation Center for Interventional Research in Radiation Oncology, The Danish Council for Strategic Research, Aarhus University, and Danish Cancer Society

Declaration of interest: The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

References

- Overgaard J, Hansen HS, Specht L, Overgaard M, Grau C, Andersen E, et al. Five compared with six fractions per week of conventional radiotherapy of squamous-cell carcinoma of head and neck: DAHANCA 6 and 7 randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2003;362:933–40.

- Manikantan K, Dwivedi RC, Sayed SI, Pathak KA, Kazi R. Current concepts of surveillance and its significance in head and neck cancer. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 2011;93:576–82.

- Digonnet A, Hamoir M, Andry G, Haigentz M, Jr, Takes RP, Silver CE, et al. Post-therapeutic surveillance strategies in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 2013;270:1569–80.

- Pagh A, Vedtofte T, Lynggaard CD, Rubek N, Lonka M, Johansen J, et al. The value of routine follow-up after treatment for head and neck cancer. A national survey from DAHANCA. Acta Oncol 2013;52:277–84.

- Kothari P, Trinidade A, Hewitt RJ, Singh A, O’Flynn P. The follow-up of patients with head and neck cancer: An analysis of 1,039 patients. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 2011;268:1191–200.

- Agrawal A, deSilva BW, Buckley BM, Schuller DE. Role of the physician versus the patient in the detection of recurrent disease following treatment for head and neck cancer. Laryngoscope 2004;114:232–5.

- Mortensen HR, Overgaard J, Specht L, Overgaard M, Johansen J, Evensen JF, et al. Prevalence and peak incidence of acute and late normal tissue morbidity in the DAHANCA 6 & 7 randomised trial with accelerated radiotherapy for head and neck cancer. Radiother Oncol 2012;103: 69–75.

- Hoff CM. Importance of hemoglobin concentration and its modification for the outcome of head and neck cancer patients treated with radiotherapy. Acta Oncol 2012;51:419–32.

- Hoff CM, Grau C, Overgaard J. Effect of smoking on oxygen delivery and outcome in patients treated with radiotherapy for head and neck squamous cell carcinoma – a prospective study. Radiother Oncol 2012;103:38–44.

- Boysen M, Lovdal O, Tausjo J, Winther F. The value of follow-up in patients treated for squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Eur J Cancer 1992;28:426–30.

- Manikantan K, Khode S, Dwivedi RC, Palav R, Nutting CM, Rhys-Evans P, et al. Making sense of post-treatment surveillance in head and neck cancer: When and what of follow-up. Cancer Treat Rev 2009;35:744–53.

- Lester SE, Wight RG. ‘When will I see you again?‘ Using local recurrence data to develop a regimen for routine surveillance in post-treatment head and neck cancer patients. Clin Otolaryngol 2009;34:546–51.

- Ritoe SC, Krabbe PF, Kaanders JH, van dH, Verbeek AL, Marres HA. Value of routine follow-up for patients cured of laryngeal carcinoma. Cancer 2004;101:1382–9.

- Schwartz DL, Barker J, Jr., Chansky K, Yueh B, Raminfar L, Drago P, et al. Postradiotherapy surveillance practice for head and neck squamous cell carcinoma – too much for too little? Head Neck 2003;25:990–9.

- Haas I, Hauser U, Ganzer U. The dilemma of follow-up in head and neck cancer patients. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 2001;258:177–83.

- O’Meara WP, Thiringer JK, Johnstone PA. Follow-up of head and neck cancer patients post-radiotherapy. Radiother Oncol 2003;66:323–6.

- Snow GB. Follow-up in patients treated for head and neck cancer: How frequent, how thorough and for how long? Eur J Cancer 1992;28:315–6.

- Chera BS, Eisbruch A, Murphy BA, Ridge JA, Gavin P, Reeve BB, et al. Recommended patient-reported core set of symptoms to measure in head and neck cancer treatment trials. J Natl Cancer Inst 2014;106:10.1093/jnci/dju127.

- de Visscher AV, Manni JJ. Routine long-term follow-up in patients treated with curative intent for squamous cell carcinoma of the larynx, pharynx, and oral cavity. Does it make sense? Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1994;120:934–9.

- Nisa L, La Macchia R, Boujelbene N, Sandu K, Khanfir K, Giger R. Correlation between subjective evaluation of symptoms and objective findings in early recurrent head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2013;139:687–93.

- Mukherji SK, Mancuso AA, Kotzur IM, Mendenhall WM, Kubilis PS, Tart RP, et al. Radiologic appearance of the irradiated larynx. Part II. Primary site response. Radiology 1994;193:149–54.