Abstract

Background: Several biomarkers of treatment efficacy have been associated with a better prognosis in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC). The prognostic significance of biomarkers in the early treatment phase is unclear.

Material and methods: In a complete national cohort of mRCC patients receiving first-line tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKI) or interleukin-2 based immunotherapy (IT) from 2006 to 2010, overall survival (OS) was analysed for baseline International mRCC Database Consortium (IMDC) classification factors and on-treatment time-dependent biomarkers obtained day 1 each cycle week 4–12 after treatment initiation with multivariate analysis and bootstrap validation.

Results: A total of 735 patients received first-line TKI (59%) or IT (41%). Median OS was overall 14.0 months and 33.4, 18.5, and 5.8 months for baseline IMDC favourable, intermediate, and poor risk groups, respectively (p < 0.0001). Systolic blood pressure ≥140 mmHg, neutrophils < lower level of normal (LLN), platelets < LLN, sodium ≥ LLN, and LDH ≤1.5 times upper level of normal after treatment initiation were significantly associated with favourable OS independent of baseline IMDC risk group in multivariate analyses stratified for TKI and IT (p ≤ 0.04). Concordance (C)-index for IMDC classification alone was 0.625 (95% CI 0.59–0.66) and combined with the five-factor biomarker profile 0.683 (95% CI 0.64–0.72). For patients with good (3–5 factors) and poor (0–2 factors) biomarker profile median OS were 23.5 and 9.6 months, respectively (p < 0.0001). Adding the five-factor biomarker profile significantly improved prognostication in IMDC intermediate (25.7 vs. 12.0 months, p < 0.0001) and poor (12.8 vs. 6.4 months, p < 0.0001) risk groups. A trend was seen in IMDC favourable risk group (38.9 vs. 28.7 months, p = 0.112).

Conclusion: On-treatment hypertension, neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, LDH below 1.5 times upper level of normal, and normal sodium, obtained week 4–12 of treatment, are independent biomarkers of favourable outcome in mRCC, independent of treatment type.

The introduction of tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKI) has resulted in a major change in the treatment of patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC). Overall survival (OS) has been improved and a higher number of patients are now able to receive treatment compared with the cytokine era [Citation1]. However, mRCC is a heterogeneous disease where patients vary with regard to their disease course and many real-life patients still have a poor outcome. An early identification of patients with a higher probability to benefit from treatment would aid the clinical decision whether to keep these patients on treatment or consider alternative treatment options. Biomarkers to improve prognostication or to predict responsiveness to a particular treatment are therefore highly needed.

For patients treated with TKI, the development of hypertension [Citation2–4], hypothyroidism [Citation5], or thrombocytopenia [Citation4] during treatment have independently been associated with improved OS. The development of neutropenia [Citation4] during treatment or normal baseline sodium [Citation6–8] have independently been associated with favourable outcome both for patients treated with TKI or immunotherapy. However, adding these biomarkers to established prognostic models [Citation9–13] have not been attempted and the clinical implication of the biomarkers restricted to the early treatment phase is unknown.

The aim of this study was to assess paraclinical data obtained week 4–12 after treatment initiation in a complete national cohort of mRCC patients and to integrate independent biomarkers in an established prognostic model in order to improve prognostication.

Patients and methods

This population-based analysis comprised a complete national cohort of Danish patients who received TKI (sorafenib and sunitinib) or interleukin-2 (IL2)-based immunotherapy (subcutaneous low-dose IL2 mainly administered as a two-week on/two-week off schedule and interferon-alpha given four weeks on) as first-line treatment from 1 January 2006 to 31 December 2010. The clinical results have previously been published [Citation1]. A central pathology review confirmed mRCC. Baseline patient characteristics, outcome data, and paraclinical data were collected retrospectively with uniform data collection templates. Blood pressure (BP) and blood samples (BS) were measured on day 1 in each cycle for the first 12-week on treatment (week 4–12). BS were standardised to upper (ULN) and lower level of normal (LLN) for the treating hospital. If neutrophils or platelets were measured below LLN, haemoglobin or sodium at or above LLN, calcium at or below ULN, LDH at or below 1.5 × ULN, and thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) above ULN at any time after baseline but within or equal to 12 week (week 4–12) after treatment initiation the patient would remain in the category despite subsequent reversal of values. Hypertension was defined as systolic BP (SBP) above or equal to 140 mmHg or diastolic BP (DBP) above or equal to 90 mmHg.

Statistical analysis

OS was defined from start of first-line treatment to death of any cause. Patients alive were censored at time of last follow-up. Data were right-censored. Patients who emigrated (n = 4) were censored at time of last contact. OS was calculated with Kaplan-Meier method and median follow-up with the reverse Kaplan-Meier method. All analyses were complete cases.

BS and BP within 12 weeks (week 4–12) after treatment initiation were analysed as binary time-dependent covariates along with baseline IMDC risk groups in a univariate Cox proportional hazard model. A multivariable time-dependent Cox regression analysis with time-dependent covariates and baseline IMDC risk groups including covariates with a univariate p ≤ 0.1 was performed. The model was then reduced retaining covariates with two-sided p < 0.05. The model was stratified for TKI and IL2-based therapies after prior test for interaction between drug and time-dependent covariates and analysed separately for TKI and IL2-based therapy.

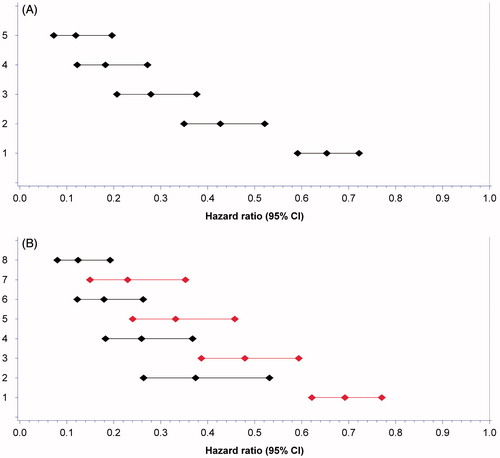

A prognostic index was constructed based on all significant time-dependent covariates from the stratified multivariate model. A forest plot was created to demonstrate the effect of adding covariates to the index by assigning all significant time-dependent variables 1 point each except LDH and then scored by the sum. The multivariate model was validated internally with bootstrap analysis with 300 random samples. Concordance (C)-index was used to evaluate both the original and the bootstrap models predictive accuracy where a value of 0.5 represents no predictive accuracy and 1 represents complete accuracy that is patients predicted to survive will actually survive [Citation14].

Database management and statistical calculations were performed using SAS (v9.3, SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) and R [R Core Team (2013)].

Ethics

The study was approved by the Danish Health Authorities, the Danish Research Ethics Committee and the Danish Data Protection Agency. The study was registered with ClinicalTrials.gov NCT01339962.

Results

Patients

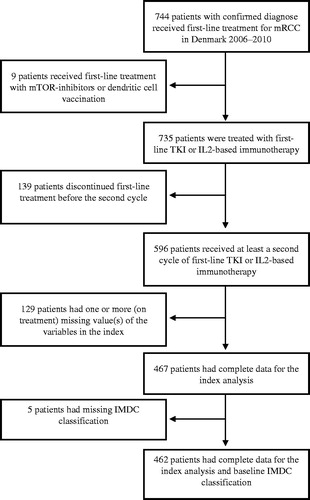

Patient characteristics are summarised in . A total of 735 patients started first-line treatment; 431 patients received TKI (sunitinib, n = 364; sorafenib, n = 67) and 304 patients received IL2-based immunotherapy. A flowchart is shown in . In total 596 (81%) of the 735 patients received at least a second cycle and were evaluable for time-dependent analyses. After initiation but within 12-week (week 4–12) treatment 451 (82%), 88 (16%), and 153 (28%) patients had sodium ≥ LLN, platelets < LLN, and neutrophils < LLN, respectively. A total of 224 (56%) patients had SBP ≥140 mmHg () of which 50 patients were treated with IL2-based immunotherapy.

Figure 1. Flowchart of first-line patients with mRCC treated with TKI or IL2-based immunotherapy. IL2, interleukin-2; IMDC, International mRCC Database Consortium; mRCC, metastatic renal cell carcinoma; mTOR, mammalian target of rapamycin; TKI, tyrosine kinase inhibitor.

Table I. Baseline characteristics of patients receiving first-line TKI and IL2-based immunotherapy for metastatic renal cell carcinoma.

Table II. Univariate analyses of time-dependent covariates after the first cycle but within the first 12 weeks (week 4–12) on first-line treatment of patients with mRCC stratified by TKI and IL2-based immunotherapy.

Median OS for all patients was 14.0 months [95% confidence interval (CI) 12.4–15.5] and 33.4, 18.5, and 5.8 months for IMDC favourable, intermediate, and poor risk group (p < 0.0001), respectively, with a median follow-up of 50.2 months (range 1.9–81.8). Median OS was 2.5 months (95% CI 1.9–3.6) for the 139 patients who did not start a second cycle of treatment.

Univariate analyses

Univariate analyses were stratified for TKI and IL2-based immunotherapy. The time-dependent variables obtained within 12 weeks (week 4–12) after treatment initiation that were significantly associated with longer OS are given in . SBP ≥140 mmHg and DBP ≥90 mmHg were both significantly associated with favourable OS but these were highly correlated (data not shown). SBP was therefore included in the multivariate analyses as the association with OS was the strongest.

Patients with SBP ≥140 mmHg within 12 weeks (week 4–12) treatment had a median OS of 18.4 (95% CI 15.3–22.3) versus 15.1 (95% CI 11.2–20.1) months for patients with SBP < 140 mmHg (p = 0.0206). Patients treated with IL2-based immunotherapy and SBP ≥140 mmHg had a median OS of 34.5 (95% CI 18.9–31.4) versus 22.7 (95% CI 24.0–NA) months for patients with SBP <140 mmHg (p = 0.0274). Patients with sodium ≥ LLN had a median OS of 19.8 (95% CI 18.0–22.4) versus 8.3 (95% CI 6.5–13.5) months for sodium < LLN (p < 0.0001).

Few patients had complete data to examine changes from baseline to on-treatment, however, OS for 53 patients with normalisation of sodium (≥LLN) from baseline < LLN was 11.5 (95% CI 10.6–20.1) compared to 6.5 months (95% CI 4.9–11.2) for 56 patients with unchanged sodium < LLN (p = 0.0039). Only 41 of 72 patients with baseline LDH >1.5 times ULN started a second cycle of first-line treatment. Twelve patients obtained LDH ≤1.5 times ULN within 12 weeks (week 4–12) of treatment resulting in almost doubling OS to 7.7 (95% CI 6.5–NA) compared to 4.1 (95% CI 3.6–8.1) months for 20 patients with unchanged LDH levels >1.5 times ULN (p = 0.0481).

Multivariate analysis

There was an interaction between haemoglobin and treatment type; demonstrating an OS benefit for patients treated with IL2-based immunotherapy with normal haemoglobin values during therapy while there was no effect for TKI-treated patients. No other interactions between type of treatment and time-dependent covariates in the multivariate analyses were found (data not shown). Removal of haemoglobin from the multivariate analysis enabled stratification for TKI and IL2-based immunotherapy (). Eight patients were excluded due to missing values.

In multivariate analysis, LDH ≤1.5 times ULN within 12 weeks (week 4–12) after treatment initiation was the strongest predictor of OS among the five significant time-dependent covariates with a hazard ratio (HR) of 0.45 (95% CI 0.31–0.66, p < 0.0001). Sodium ≥ LLN was independently associated with improved OS with HR of 0.63 (95% CI 0.49–0.80, p = 0.0002). Similar significant HRs for OS were observed for SBP ≥140 mmHg, and neutrophils or platelets < LLN. These time-dependent covariates were significantly associated with OS independent of baseline IMDC risk group status. Comparable results were seen if DBP was used instead of SBP (data not shown). The C-index for baseline IMDC risk group alone in this heterogeneous cohort was 0.625 (CI 0.59–0.66) and increased to 0.683 (CI 0.64–0.72) when baseline IMDC risk group was combined with the five time-dependent covariates. HRs were almost similar when multivariate analyses were restricted to patients treated with TKI and IL2-based therapy separately, but did not reach similar significance levels for all variables probably due to low patient numbers in subgroups (Supplementary Table I, available online at http://www.informahealthcare.com).

Table III. Multivariate analyses with bootstrap analysis of time-dependent covariates after the first cycle but within the first 12 weeks (week 4–12) on first-line treatment of patients with mRCC stratified by TKI and IL2-based immunotherapy. N = 588.

More extreme values within the first 12-weeks of treatment (week 4–12), such as neutropenia grade 2 (<1.5 × 109/L) or higher levels of sodium than LLN were associated with even longer OS [HR 0.60 (95% CI 0.40–0.91, p = 0.0151 using cut-off for neutrophils of <1.5 × 109/L]. Cut-offs with LLN and ULN were chosen because they are practical and easy-to-use in the routine clinic. It also illustrates that less extreme values are sufficient to predict outcome.

Bootstrap validation

The multivariate analysis was internally validated with 300 random bootstrap samples (). The mean HRs were similar to the original model. The C-index from the bootstrap analysis with combined five covariates and IMDC risk groups was 0.685.

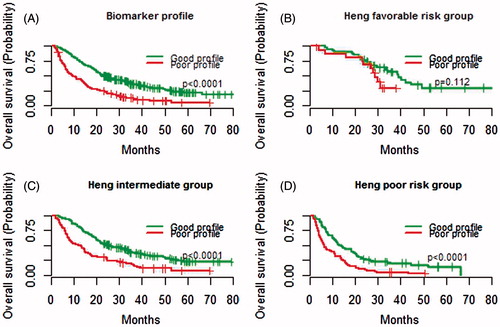

Biomarker index

All significant time-dependent variables were assigned 1 point each: LDH ≤1.5 times ULN, SBP ≥140 mmHg, sodium ≥ LLN, neutrophils or platelets < LLN. Any combinations of 1–5 biomarkers in a constructed biomarker index gradually reduced the HR for death with the lowest HR seen in the index comprising all five biomarkers (). LDH had higher weight than the other covariates (black bars in ) but was still assigned 1 point to create a feasible and easy-to-use tool. Of 596 patients that received at least two cycles of treatment, 467 patients had complete data available. Patients were assigned a biomarker profile based on numbers of favourable features; good biomarker profile (3–5 biomarkers) and poor biomarker profile (0–2 biomarkers) with median OS from baseline of 23.5 (95% CI 20.8–28.0) and 9.6 (95% CI 7.2–13.8) months (p < 0.0001), respectively (, ). For the 462 patients with complete baseline and biomarker data, OS for IMDC favourable, intermediate, and poor risk group was 33.4 (95% CI 28.7–44.7), 19.8 (95% CI 17.4–23.8), and 9.0 (95% CI 7.4–11.4) months, respectively. OS for patients with good versus poor biomarker profile in IMDC poor prognostic group was 12.8 (95% CI 10.7–19.8) and 6.4 (95% CI 5.2–10.8) months, respectively, and for patients in IMDC intermediate risk group 25.7 (95% CI 20.9–33.6) and 12.0 (95% CI 7.9–16.5) months (both p < 0.0001), respectively ( and ). A separation of OS per biomarker profile was observed for patients in IMDC favourable risk group [38.9 (95% CI 29.7–NA) and 28.7 (95% CI 23.4–NA) months, p = 0.112], though not significant probably due to the low number of patients (n = 57).

Figure 2. Forest plot of hazard ratio’s (HR) for survival from combining biomarkers stratified for first-line treatment with tyrosine kinase inhibitors and interleukin-2 based immunotherapy. (A) HR for adding a favourable biomarker to the index adjusted for Heng risk group status. Combining all 5 favourable biomarkers resulted in the lowest HR compared to an index consisting of only two, three or four favourable biomarkers. 1. Any biomarker. 2. Any two biomarkers. 3. Any three biomarkers. 4. Any four biomarkers. 5. All five biomarkers. (B) HR of adding a biomarker to the index with (black bars) or without (red bars) LDH to assess the impact of LDH on the index. 1. Any biomarker not containing LDH. 2. LDH alone. 3. Any two biomarkers not containing LDH. 4. LDH and any biomarker. 5. Any three biomarkers not containing LDH. 6. LDH and any two biomarkers. 7. All four biomarkers not containing LDH. 8. LDH and any three biomarkers.

Figure 3. Kaplan-Meier estimates of median overall survival (OS) per biomarker profile and combined with baseline International Metastatic renal cell carcinoma Database Consortium (IMDC) risk group status. A good biomarker profile comprised 3–5 biomarkers within 12-weeks after treatment initiation and a poor profile 0–2 biomarkers. (A) OS for patients with a good versus poor biomarker profile. (B) OS for patients in IMDC favourable risk group with a good versus poor biomarker profile. (C) OS for patients in IMDC intermediate risk group with a good versus poor biomarker profile. (D) OS for patients in IMDC poor risk group with a good versus poor biomarker profile.

Table IV. Biomarker index.

Table V. Overall survival per biomarker profile per IMDC risk group for patients with mRCC stratified by TKI and IL2-based immunotherapy.

Discussion

This study is to our knowledge the first to demonstrate that systolic hypertension, neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, LDH ≤1.5 times ULN, and normal sodium assessed week 4–12 after treatment initiation are independent prognostic biomarkers associated with improved OS for patients with mRCC. These five biomarkers were able to predict OS independent of baseline IMDC variables and irrespectively of treatment type and may therefore be considered as true prognostic factors. Adjusted for baseline IMDC classification the biomarker index provided additional significant prognostic information for patients in IMDC intermediate and poor prognostic groups and also provided prognostic information in IMDC favourable group, albeit not statistically significant, probably due to the low number of patients. Our findings may reflect treatment-induced tumour biology alterations suggesting that prognostic risk features are dynamic variables – instead of static – that need readjustment during treatment.

Along with the detection of new biomarkers [Citation15] inclusion of biomarkers in established prognostic models [Citation9–13] is needed for improved prognostication and individualised therapies for patients [Citation16]. Our biomarker index is readily available, easily obtained, and routinely measured during clinical visit. Importantly, the biomarker index provide clinically meaningful information by adjusting prognosis and early counselling especially for poor and intermediate risk patients before the first computed tomography assessment routinely obtained at a three-month time point on top of baseline IMDC prognostic stratification.

Low sodium at baseline has been shown to predict poor OS for both targeted therapy and immunotherapy [Citation6–8] but the significance of reversal to normal sodium during treatment has until now been unknown. The mechanism behind hyponatraemia is not clearly understood but a relation to chronic inflammation caused by elevated interleukin-6 has been suggested [Citation7,Citation17]. Hyponatraemia could also be caused by renal impairment though both Jeppesen et al. [Citation6] and Kawashima et al. [Citation7] could not find a correlation between hyponatraemia and estimated glomerular filtration rate, adrenal metastases, or nephrectomy. Similarly, Marfarlane et al. [Citation18] found that impaired renal function did not impact objective response or OS for patients treated with vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)-targeted therapy. Other factors, such as co-morbidity or diuretics [Citation19,Citation20] could influence the development of hyponatraemia and this area needs further research.

Elevated LDH at baseline has been shown to predict poor OS in patients with mRCC [Citation9,Citation11,Citation12,Citation16] but the significance of LDH below 1.5 times ULN during treatment has not been analysed previously. In our analysis LDH had higher weight with HR of 0.45 compared to other biomarkers. However, to establish a simple and easy-to-use tool all variables were assigned 1 point each in the biomarker index.

Elevated TSH has been associated with improved outcome by others [Citation3,Citation5,Citation21,Citation22] but was not associated with OS in our study. Many of our patients did not have TSH measured prior to each treatment cycle which resulted in a high amount of missing values and this may have influenced our results.

Several studies have shown that adverse events, such as hypertension, thrombocytopenia and neutropenia are biomarkers of efficacy in patients treated with targeted therapy [Citation2–5]. We validated these findings and also extended the findings to be evident during the early treatment phase independent of type of therapy. However, it is counterintuitive that hypertension is a biomarker of efficacy in IL2-based immunotherapy as it often results in hypotension when administered. Both activation of the endothelin-1 axis [Citation23] and inhibition of vascular relaxation due to decreased production of nitric oxide have been mentioned to lead to hypertension which is a group effect of VEGF inhibitors [Citation24]. Whether hypertension between IL-2 courses is due to the same mechanism is unclear. BP values were obtained at every cycle initiation after a two-week treatment break from IL2 which may explain our findings as it could be related to baseline hypertension [Citation2]. Multivariate analyses looking at changes from baseline to on-treatment values were not possible due to a high amount of missing values.

We have recently shown that implementation of targeted therapy did not lead to an increase in total health care costs per patient per treatment year compared with a pre-TKI era [Citation25]. However, we have also previously shown that patients in IMDC poor prognostic group had limited OS benefit from treatment [Citation1]. The implication of our present study is that baseline adverse prognostic features established by Motzer and IMDC [Citation9,Citation10] can be supplemented with early on-treatment biomarkers for improved prognostication thereby better identifying patients that will benefit from treatment. Adding the prognostic index to IMDC poor risk group adjusted prognostication as patients with a good biomarker profile during early treatment had doubled OS compared to patients with a poor biomarker profile. Similar separation was observed for IMDC intermediate prognostic group and a trend was seen in the favourable group. Thus, the biomarker index identifies a subgroup of IMDC patients that achieve clear survival benefit from treatment. This tool may therefore aid clinicians with supplementary prognostic information to guide treatment counselling with the patient. However, our index needs validation in another cohort and further testing of the relation to outcome in patients treated with mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR)-inhibitors is needed as well as prospective testing.

Limitations are the retrospective design, missing data and low number of patients in IMDC favourable risk. Not all available published baseline prognostic factors were included in the multivariate model. However, we controlled for IMDC status as no other prognostic models have shown improved accuracy [Citation13]. Also, the effect of the biomarkers may have been underestimated as they were measured day 1 each cycle after a treatment break for sunitinib and IL-2.

Conclusion

On-treatment hypertension, neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, LDH below 1.5 times upper level of normal, and normal sodium, obtained week 4–12 of treatment, are independent biomarkers of favourable outcome in mRCC, independent of treatment type.

Supplementary Material available online. Supplementary Table I

Suppl.zip

Download Zip (17.2 KB)Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Pfizer; Axel Muusfeldts fund; Christian Larsen and judge Ellen Larsens fund; Else and Mogens Wedell-Wedellsborgs Fund; Timber merchant Johannes Fogs Fund; Svend H.A. Schroeder and wife Ketty K. Larsen Fund; Novartis grant and the Department of Oncology and Research Fund at Herlev University Hospital. Results of this study were presented at the 2014 ESMO conference September 26–30, 2014, Madrid, Spain (poster presentation).

Declaration of interest

A.V. Soerensen has received travel grants to conferences and research grants from Pfizer and Novartis. F. Donskov has received research grants from the research fund of central Denmark Region, Novartis and GSK. R. Sandin is an employee at Pfizer and has stockownership in Pfizer. All remaining authors have no conflict of interest.

References

- Soerensen AV, Donskov F, Hermann GG, Jensen NV, Petersen A, Spliid H, et al. Improved overall survival after implementation of targeted therapy for patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma: Results from the Danish Renal Cancer group (DARENCA) study-2. Eur J Cancer 2014;50:553–62.

- Rini BI, Cohen DP, Lu DR, Chen I, Hariharan S, Gore ME, et al. Hypertension as a biomarker of efficacy in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma treated with sunitinib. J Natl Cancer Inst 2011;103:763–73.

- Bono P, Rautiola J, Utriainen T, Joensuu H. Hypertension as a predictor of sunitinib treatment outcome in metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Acta Oncol 2011;50:569–73.

- Rautiola J, Donskov F, Peltola K, Joensuu H, Bono P. Sunitinib-induced hypertension, neutropenia and thrombocytopenia as predictors of good prognosis in metastatic renal cell carcinoma patients. BJU Int Epub 2014 Sep 23.

- Schmidinger M, Vogl UM, Bojic M, Lamm W, Heinzl H, Haitel A, et al. Hypothyroidism in patients with renal cell carcinoma: Blessing or curse? Cancer 2011;117:534–44.

- Jeppesen AN, Jensen HK, Donskov F, Marcussen N, von der Maase H. Hyponatremia as a prognostic and predictive factor in metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Br J Cancer 2010;102:867–72.

- Kawashima A, Tsujimura A, Takayama H, Arai Y, Nin M, Tanigawa G, et al. Impact of hyponatremia on survival of patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma treated with molecular targeted therapy. Int J Urol 2012;19:1050–7.

- Schutz FA, Xie W, Donskov F, Sircar M, McDermott DF, Rini BI, et al. The impact of low serum sodium on treatment outcome of targeted therapy in metastatic renal cell carcinoma: Results from the International Metastatic Renal Cell Cancer Database Consortium. Eur Urol 2014;65:723–30.

- Motzer RJ, Mazumdar M, Bacik J, Berg W, Amsterdam A, Ferrara J. Survival and prognostic stratification of 670 patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol 1999;17:2530–40.

- Heng DY, Xie W, Regan MM, Warren MA, Golshayan AR, Sahi C, et al. Prognostic factors for overall survival in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma treated with vascular endothelial growth factor-targeted agents: Results from a large, multicenter study. J Clin Oncol 2009;27:5794–9.

- Motzer RJ, Bacik J, Murphy BA, Russo P, Mazumdar M. Interferon-alfa as a comparative treatment for clinical trials of new therapies against advanced renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol 2002;20:289–96.

- Manola J, Royston P, Elson P, McCormack JB, Mazumdar M, Négrier S, et al. Prognostic model for survival in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma: Results from the international kidney cancer working group. Clin Cancer Res 2011;17:5443–50.

- Heng DY, Xie W, Regan MM, Harshman LC, Bjarnason GA, Vaishampayan UN, et al. External validation and comparison with other models of the International Metastatic Renal-Cell Carcinoma Database Consortium prognostic model: A population-based study. Lancet Oncol 2013;14:141–8.

- Harrell FE Jr, Lee KL, Mark DB. Multivariate prognostic models: Issues in developing models, evaluating assumptions and adequacy, and measuring and reducing errors. Stat Med 1996;15:361–87.

- Tran HT, Liu Y, Zurita AJ, Lin Y, Baker-Neblett KL, Martin AM, et al. Prognostic or predictive plasma cytokines and angiogenic factors for patients treated with pazopanib for metastatic renal-cell cancer: A retrospective analysis of phase 2 and phase 3 trials. Lancet Oncol 2012;13:827–3.

- Donskov F, von der Maase H. Impact of immune parameters on long-term survival in metastatic renal cell carcinomas. J Clin Oncol 2006;24:1997–2005.

- Hashizume M, Higuchi Y, Uchiyama Y, Mihara M. IL-6 plays an essential role in neutrophilia under inflammation. Cytokine 2011;54:92–9.

- Marfarlane R, Heng DY, Xie W, Knox JJ, McDermott DF, Rini BI, et al. The impact of kidney function on the outcome of metastatic renal cell carcinoma treated with vascular endothelial growth factor-targeted therapy. Cancer 2012;118:365–70.

- Spital A. Diuretic-induced hyponatremia. Am J Nephrol 1999;19:447–52.

- Gankam-Kengne F, Ayers C, Khera A, de Lemos J, Maalouf NM. Mild hyponatremia is associated with increased risk of death in an ambulatory setting. Kidney Int 2013;83:700–6.

- Riesenbeck LM, Bierer S, Hoffmeister I, Köpke T, Papavassilis P, Hertle L, et al. Hypothyroidism correlates with a better prognosis in metastatic renal cell cancer patients treated with sorafenib and sunitinib. World J Urol 2011;29:807–13.

- Franzke A, Peest D, Probst-Kepper M, Buer J, Kirchner GI, Brabant G, et al. Autoimmunity resulting from cytokine treatment predicts long-term survival in patients with metastatic renal cell cancer. J Clin Oncol 1999;17:529–33. Erratum in J Clin Oncol 1999;17:1330.

- Lankhorst S, Kappers MH, van Esch JH, Danser AH, van der Meiracker AH. Hypertension during vascular endothelial growth factor inhibition: Focus on nitric oxide, endothelin-1, and oxidative stress. Antioxid Redox Signal 2014;20:135–45.

- Klümpen HJ, Samer CF, Mathijssen RH, Schellens JH, Gurney H. Moving towards dose individualization of tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Cancer Treat Rev 2011;37:251–60.

- Soerensen AV, Donskov F, Kjellberg J, Ibsen R, Hermann GG, Jensen NV, et al. Health economic changes as a result of implementation of targeted therapy for metastatic renal cell carcinoma: National results from Darenca study 2. Eur Urol 2014;68:516–22.