Abstract

Background Upper gastro-intestinal cancer (UGIC) includes malignancies in esophagus, stomach and small intestine, and represents some of the most frequent malignancies worldwide. The aim of the present analysis was to describe incidence, mortality and survival in UGIC patients in Denmark from 1980 to 2012 according to differences in age and time periods.

Material and methods UGIC was defined as ICD-10 codes C15-C17. Data derived from the NORDCAN database with comparable data on cancer incidence mortality, prevalence and relative survival in the Nordic countries, where the Danish data were delivered from the Danish Cancer Registry and the Danish Cause of Death Registry with follow-up for death or emigration until the end of 2013.

Results The proportion of male patients over the age of 70 years diagnosed with esophageal cancer was constant over time (around 42%) but increased in females to 49% in 2012. Incidence rates increased with time and continued to rise in all ages. Mortality rates were clearly separated by age groups with increasing mortality rates by increasing age group for both sexes. Relative survival increased slowly over time in all age groups. The proportion of older male and female patients with stomach cancer increased to 50% and 54%, respectively, in 2012. Incidence rates decreased steadily with time, especially from 1980 to 1990 but continued to decrease in all age groups. Mortality rates decreased considerably from 1980 to 90 and have been almost constant during the last decade for both women and men. Relative survival increased modest over time in both genders and all age groups. In 2012, only 1471 persons were alive after a diagnosis of stomach cancer.

Conclusion There is a need for clinical trials focusing on patients over the age of 70 years with co-existing comorbidity.

Malignancies of the digestive organs including esophagus, stomach and small intestine are a heterogeneous group of diseases often with a dismal prognosis. Gastro-esophageal cancer is the second most frequent malignancy worldwide and the second most common cause of cancer related death. Together they account for nearly 1.4 million new cases and 1.1 million deaths every year [Citation1,Citation2]. In Europe, gastro-esophageal cancer is the fourth most common cancer but the third most common cause of cancer-related deaths [Citation3]. In most developed countries, life expectancy has increased considerably [Citation4], thereby dramatically increasing the proportion of people older than 65 years. As age is the main risk factor for cancer, cancer treatment of the elderly will become a major challenge to the healthcare systems. During the last decade there has been an increasing interest in geriatric oncology leading to an improved clinical management of elderly [Citation5,Citation6]. Knowledge about efficacy and toxicity to chemotherapy, radiation and targeted therapy is primarily derived from clinical trials including highly pre-selected and fit patients. However, in several trials of patients with stomach cancer, older patients were often excluded leading to a median age of 60 years for patients included in clinical trials [Citation7]. It seems unlikely that the results obtained from such clinical trials can be applied to unselected patient populations who are 10–20 years older and may suffer from comorbidity. There is also a risk that therapy is not offered to fit elderly patients.

The aim of the present study was to describe incidence, mortality and survival in patients diagnosed with esophageal, stomach and small intestine cancer according to differences in age and time periods.

Material and methods

Cancer of the esophagus was defined as ICD-10 code C15, stomach C16 and small intestines C17. A more detailed description of the materials and methods appear elsewhere [Citation8]. In brief, data were derived from the NORDCAN database which include comparable data on cancer incidence, mortality, prevalence and relative survival in the Nordic countries, where the Danish data are delivered from the Danish Cancer Registry and the Danish Cause of Death Registry with follow-up for death or emigration until the end of 2013. This study focuses on the elderly population with age categorized as 0–69, 70–79, 80–89 and 90 + years.

For incidence and mortality, age group-specific numbers and rates per 100 000 person years are shown in tables and graphs with calendar periods for time of diagnosis 1978–1982, 1988–1992, 1998–2002, 2003–2007, 2010, 2011 and 2012. Prevalence is defined as the number of cancer patients (including cured patients as well) with that specific diagnosis still alive and is shown in tables by the end of 1980, 1990, 2000, 2005, 2010, 2011 and 2012.

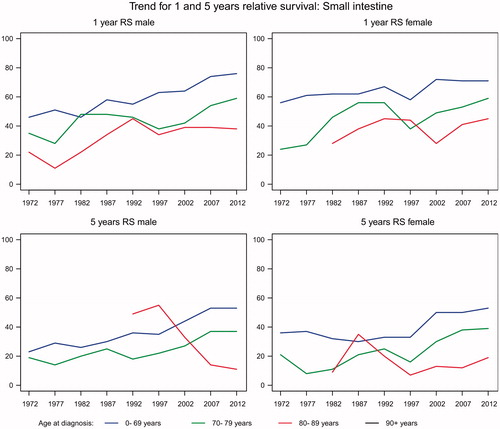

Sex- and age-specific one- and five- year relative survival proportion ratios were calculated for each of the diagnostic groups for the age groups 0–69, 70–79, 80–89 and 90 + years and for the five-year periods of diagnosis 1968–1972, 1973–1977, …, 2003–2007 and 2008–2012.

Relative survival for a group of cancer patients was calculated as the observed survival (where all causes of death are considered events) divided by the expected survival for a group from the Danish population with the same age and year of birth composition. The actuarial method was used for observed survival and the Ederer II method for expected survival [Citation9]. Relative survival can be interpreted as the survival if the cancer was the only cause of death. For the most recent period, 2008–2012, not all patients can be followed up for death in five years and we used hybrid methods where we supplement with survival experience from cancer patients diagnosed earlier years. Survival was not calculated for cancer groups with less than five patients [indicated by (-) in tables and blank in the graphs]. If all patients died in the follow-up period resulting in zero survival this is indicated as 0 (-) and if calculation for a cell results in a relative survival higher than 100% the result is shown in tables, but restricted to 100% in graphs.

Results

Esophagus

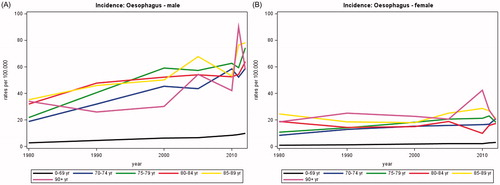

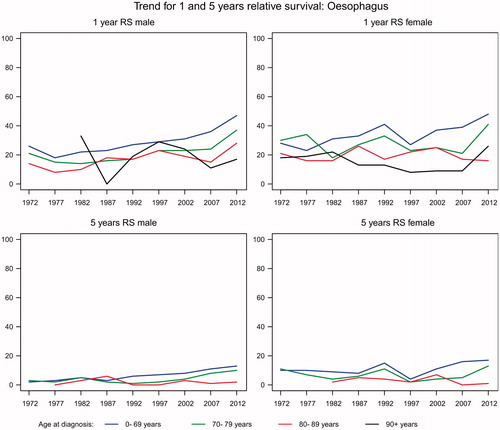

The average annual number of new cases of esophageal cancer rose from 172 in 1980 to 571 in 2012 of whom 43–49% were over the age of 70 years. The number of deaths increased in parallel to 448 in 2012. The incidence rates were about twice as high for men as for women and increased with increasing age (). Similar trends were seen for mortality rates (not shown). For both men and women the relative one-year survival increased with time for all age groups, but is still low about 48% for patients aged less than 70 years and about 40% for those aged 70–79 years (). Although also improving, the relative five-year survival barely exceeded 15% in all age groups.

Stomach

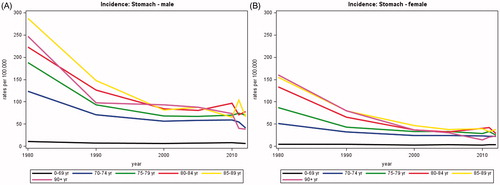

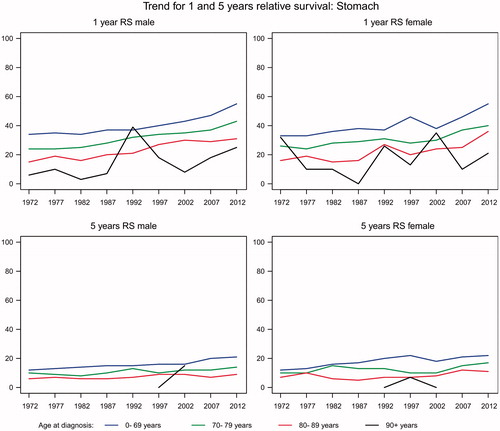

The average annual number of new stomach cancers decreased from 972 in 1980 to 500 in 2012, of whom about half were less than 70 years and half more than 70 years. There was a clear trend of decreasing incidence by age group, most pronounced for those aged 85 or more years (). The total annual number of deaths decreased considerably from 871 in 1980 to 414 in 2012. In both men and women aged less than 70 years, the relative one-year survival increased from 34% in 1980 to 55% in 2012 while the five-year relative survival increased from 12% to 22% (). Similar trends were observed in patients aged more than 70 but the relative survival decreased with increasing age. These numbers were reflected in the prevalence, with a decrease from 1777 in 1980 to 1569 in 2012.

Small intestine

Tumors of the small intestine are rare with an average annual number of new cases rising from 68 in 1980 to 142 in 2012. In patients younger than 70 years, the relative one-year overall survival increased from about 50% to about 75% and similar improvements were observed among patients over the age of 70 years though the survival was lower in this age group. The same trend was seen in the five-year survival ().

Discussion

The purpose of the present study was to examine population-based changes according to an ageing population. Up-to-date knowledge on cancer incidence, mortality and survival data are important for planning programs for cancer control at the national level. Cancers of the esophagus, stomach and small intestine represent a diverse group of cancers both according to anatomical site and histological subtypes [Citation10]. Earlier detection, centralization, introduction of chemo and/or radiotherapy for more advanced cancers may contribute to an increase in one-year survival, whereas better patient selection and staging, pre- and post-operative chemo and/or radiotherapy may contribute to improved five-year survival. Not surprisingly, increasing age was associated with a decrease in overall one- and five-year survival for all three cancer sites, despite taking background mortality into account. Compared to younger patients, the typical elderly patient has higher operative mortality and thus curative resection will not be offered to elderly patients with co-morbidity.

In patients with esophageal cancer there was an increasing incidence and mortality during the study period. The one- and five-year survival increased in both genders and among different age groups except in patients 80 + years.

In EU, the incidence and mortality rate of stomach cancer has decreased dramatically during the decades [Citation11] and this was also reflected in the present study. No clear conclusion has been drawn in this field but better food conservation, more varied diet, decreased prevalence of Helicobacter pylori and improved standard of living in the industrialized countries are important factors [Citation12]. Especially the relative one-year survival increased in patients with stomach cancer from 1998 to 2012, but one- and five-year relative survival were still below a European standard [Citation13].

Cancer of the small intestine is a rare disease only diagnosed in 142 patients in 2012. With a study period of only five years it is difficult to perform firm statistical analyzes. However, there seems to be a slight increase in incidence and survival.

For this analysis, information was not available on morphological types and histological verification. From a recent population based trial, it was shown that the majority of patients with esophageal or stomach cancer in the region of Southern Denmark had a histologically verified diagnosis [Citation14]. This might be explained by the widespread use of open-access endoscopy even in patients with dyspepsia and no alarm symptoms. Histological verification of cancers is important since different histological types might have different prognoses. Examples are gastro-intestinal stromal tumors lymphomas or neuroendocrine tumors of the stomach with a generally better prognosis leading to long-term survival. Adenocarcinoma is the far most frequent histological subtype of cancers in the stomach often with a dismal prognosis. However, also adenocarcinomas present in different subtypes: diffuse, intestinal or with the overexpression of the human epidermal growth factor receptor-2 (HER2) protein [Citation15]. The EUROCARE-4 program estimated the age- and area-adjusted five-year relative survival to be 42% for small intestine, 25% for stomach cancer and lowest for esophageal cancer with only 11% [Citation16]. This correlated well with the finding of the Nordic cancer registries with five-year survival of esophageal cancer of 12% and small intestine cancer of 44%. In patients with stomach cancer the five-year relative survival was slightly lower with 16% [Citation13].

Study limitations

First, we had no data on cancer stage and thus were unable to evaluate whether the improvements in survival in patients were due to better treatment or diagnosis at an earlier stage. Second, it is not possible to comment on whether improvements in both one- and five-year overall survival relates to improved staging, better surgery with reduced post-operative mortality or to more effective chemotherapy and radiotherapy. Increased survival in the recent time period may relate to the use of improved imaging strategies. As an example, the inclusion of either EUS or CT-PET alone in esophageal cancer patients ≥66 years old was associated with improved one-, three- and five-year survival [Citation17]. Similarly, preliminary data suggests that older patients may benefit from minimally invasive surgery. In esophageal cancer patients older than 70 years, minimally invasive esophagectomy was associated with lower rates of morbidity and pulmonary complications as well as longer disease-specific survival time than open esophagectomy [Citation18].

Furthermore, we lack information on cigarette use, alcohol consumption and comorbidity factors that might influence treatment decisions. Unplanned hospitalization in old patients with GI cancer is a substantial problem [Citation19], and therefore geriatric assessments and better pretherapeutic comorbidity stratification are essential in selecting the optimal therapy in older cancer patients.

A potential positive effect of chemoradiation therapy, national cancer plans, centralization and multidisciplinary teams may also play a role in the overall prognosis of patients with upper GI tract cancer. In patients with esophageal, stomach or small intestine cancer chemotherapy and radiotherapy were not used routinely in Denmark before the beginning of the 2000s. Several trials have investigated the survival benefit of chemotherapy in patients with stomach cancer and a meta-analysis concluded that in patients with advanced disease chemotherapy prolongs survival and improves quality of life [Citation20]. In patients with squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus the evidence for palliative chemotherapy is still lacking but often patients are offered either radiotherapy or chemotherapy hoping to reduce cancer-specific symptoms like dysphagia. Several initiatives have been launched during the last decade to improve survival in Danish cancer patients. Among them, the implementation of the National Cancer Plan introduced in 2000 and redefined in 2005, aiming to minimize diagnostic and treatment delay. Multidisciplinary teams comprising specialized surgeons, oncologists, radiologists and pathologists have been established giving the opportunity to discuss the most optimal treatment strategy “up front”. Furthermore, both surgical and oncologic treatment of upper gastro-intestinal cancer (UGIC) has been centralized to high volume hospitals. Based on randomized trials in patients with stomach cancer [Citation21,Citation22] perioperative chemotherapy was introduced and has been a standard of care in Denmark since 2008 in patients with resectable stomach cancer [Citation23]. The peri-operative strategy is feasible in a standard population with promising short-term results (two-year survival 53%).

In conclusion, the incidence and mortality increased for both esophagus and small intestine cancer while the incidence and mortality of stomach cancer has decreased. For all three cancers one-year relative survival increased during the study period irrespective of age. As the population of people aged 70 + years will increase during the next decade’s knowledge about cancer directed therapy of elderly is urgently needed. Hopefully, trials investigating toxicity and efficacy in elderly patients might help us to establish effective and safe geriatric oncology treatment, – also in UGIC patients.

Acknowledgement

We thank Niels Christensen and Anne Mette T. Kejs, Danish Cancer Society, Department of Documentation & Quality, for making the tabulations of incidence, mortality and prevalence, calculation of relative survival and trend graphs.

References

- Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, Ferlay J, Ward E, Forman D. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin 2011;61:69–90.

- Parkin DM, Bray F, Ferlay J, Pisani P. Global cancer statistics, 2002. CA Cancer J Clin 2005;55:74–108.

- Ferlay J, Steliarova-Foucher E, Lortet-Tieulent J, Rosso S, Coebergh JW, Comber H, et al. Cancer incidence and mortality patterns in Europe: estimates for 40 countries in 2012. Eur J Cancer 2013;49:1374–403.

- Christensen K, Doblhammer G, Rau R, Vaupel JW. Ageing populations: the challenges ahead. Lancet 2009;374:1196–208.

- Bernardi D, Errante D, Tirelli U, Salvagno L, Bianco A, Fentiman IS. Insight into the treatment of cancer in older patients: developments in the last decade. Cancer Treat Rev 2006;32:277–88.

- Monfardini S. Geriatric oncology: a new subspecialty? J Clin Oncol 2004;22:4655

- Shitara K, Ikeda J, Kondo C, Takahari D, Ura T, Muro K, et al. Reporting patient characteristics and stratification factors in randomized trials of systemic chemotherapy for advanced gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer 2012;15:137–43.

- Ewertz M, Christensen K, Engholm G, Kejs AMT, Lund L, Matzen LE, et al. Trends in cancer in elderly population in Denmark, 1980-2012. Acta Oncol 2015; doi: 10.3109/0284186X.2015.1114678.

- Dickman PW, Sloggett A, Hills M, Hakulinen T. Regression models for relative survival. Stat Med 2004;23:51–64.

- Pennathur A, Gibson MK, Jobe BA, Luketich JD. Oesophageal carcinoma. Lancet 2013;381:400–12.

- Bosetti C, Bertuccio P, Malvezzi M, Levi F, Chatenoud L, Negri E, et al. Cancer mortality in Europe, 2005-2009, and an overview of trends since 1980. Ann Oncol 2013;24:2657–71.

- Fock KM. Review article: the epidemiology and prevention of gastric cancer. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2014;40:250–60.

- Gavin AT, Francisci S, Foschi R, Donnelly DW, Lemmens V, Brenner H, et al. Oesophageal cancer survival in Europe: A EUROCARE-4 study. Cancer Epidemiology 2012;36:505–12.

- Schønnemann KR, Mortensen MB, Bjerregaard JK, Fristrup C, Pfeiffer P. Characteristics, therapy and outcome in an unselected and prospectively registered cohort of patients with gastro-oesophageal cancer. Acta Oncol 2014;53:385–91.

- Lauren P. The two histological main types of gastric carcinoma: Diffuse and so-called intestinal-type carcinoma. An attempt at a histo-clinical classification.. Acta Pathol Microbiol Scand 1965;64:31–49.

- Sant M, Allemani C, Santaquilani M, Knijn A, Marchesi F, Capocaccia R. EUROCARE-4. Survival of cancer patients diagnosed in 1995-1999. Results and commentary. Eur J Cancer 2009;45:931–91.

- Wani S, Das A, Rastogi A, Drahos J, Ricker W, Parsons R, et al. Endoscopic ultrasonography in esophageal cancer leads to improved survival rates: Results from a population-based study. Cancer 2015;121:194–201.

- Li J, Shen Y, Tan L, Feng M, Wang H, Xi Y, et al. Is minimally invasive esophagectomy beneficial to elderly patients with esophageal cancer? Surg Endosc 2015;29:925–30.

- Manzano JG, Luo R, Elting LS, George M, Saurez-Almazor ME. Patterns and Predictors of Unplanned Hospitalization in a Population-Based Cohort of Elderly Patients With GI Cancer. J Clin Oncol 2014;32:3527–33.

- Wagner AD, Unverzagt S, Grothe W, et al. Chemotherapy for advanced gastric cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010 Mar 17;(3):CD004064. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004064.pub3.

- Cunningham D, Allum WH, Stenning SP, Thompson JN, Van de Velde CJH, Nicolson M, et al. Perioperative Chemotherapy versus Surgery Alone for Resectable Gastroesophageal Cancer. N Engl J Med 2006;355:11–20.

- Ychou M, Boige V, Pignon JP, Conroy T, Bouche O, Lebreton G, et al. Perioperative chemotherapy compared with surgery alone for resectable gastroesophageal adenocarcinoma: an FNCLCC and FFCD multicenter phase III trial. J Clin Oncol 2011;29:1715–21.

- Larsen AC, Holländer C, Duval L, Achiam M, Pfeiffer P, Yilmaz MK, et al. A Nationwide retrospective study of perioperative chemotherapy for gastroesophageal adenocarcinoma: tolerability, outcome, and prognostic factors. Ann Surg Oncol 2015;22:1540–47.