Abstract

Background Colorectal cancer (CRC) is a disease of the older population. The current demographic ageing leads to more elderly patients and is expected to further increase the number of patients with CRC. The objective of the present paper is to outline incidence, mortality and prevalence from 1980 to 2012 and survival data from 1968 to 2012 in Danish CRC patients focusing on the impact of ageing.

Material and methods Data were derived from the NORDCAN database with comparable data on cancer incidence, mortality, prevalence and relative survival in the Nordic countries, where the Danish data are delivered from the Danish Cancer Registry and the Danish Cause of Death Registry with follow-up for death or emigration until the end of 2013. This study focuses on the elderly population categorized in six age groups.

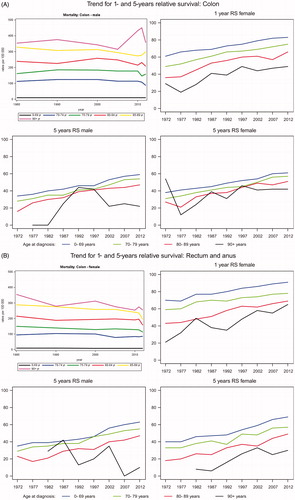

Results The incidence of CRC has increased over the past three decades. Incidence rate has increased in patients with colon cancer, but showed a decreasing trend in the oldest patients with rectal and anal cancer. Mortality has diminished in younger patients with colon cancer, but increased with increasing age. However, mortality did not increase proportionally to incidence. In rectal and anal cancer mortality has decreased, except among the oldest patients. This correlates to a decreasing incidence rate. Prevalence is widely increasing mainly because of increased incidence and longer survival, which is reflected in the increasing one- and five-year age-specific relative survival after a diagnosis of colon, rectal and anal cancer.

Conclusion The incidence of CRC is increasing, especially in older citizens, and mortality increases with older age. There is limited knowledge on how to optimize treatment in older CRC patients and future focus must be how to select and tailor the treatment for older CRC patients.

Colorectal cancer (CRC) constitutes nearly 13% of all malignancies in both males and females and with 447 000 new cases in Europe; CRC is the second most frequent cancer [Citation1]. The development of CRC is multifactorial, combining genetic susceptibility with environmental and dietary factors. Increased BMI, red meat intake, cigarette smoking, low physical activity, low vegetable consumption, and low fruit consumption are all associated with increased risk of CRC [Citation2]. Over the past two decades the survival of patients with CRC has increased constantly, not only due to a more aggressive attitude to treatment and better surgical techniques, but also due to an increased use of effective chemotherapy in the adjuvant and the metastatic situation. The median overall survival (mOS) for fit patients with metastatic CRC (mCRC) included in clinical trials has increased from six months to more than 24 months [Citation3].

CRC is a disease of the older age. There is limited knowledge about the treatment in older cancer patients, as they are under-represented in clinical trials [Citation4]. The mOS of patients included in clinical trials is longer than for patients who were not included in trials, even though they were offered similar systemic therapy [Citation5]. Older patients included in clinical trials are selected on basis of appropriate performance status and sufficient organ functions and these patients are therefore not representative of the majority of older patients who are treated in every day practice.

The present paper evaluates CRC in Denmark up to 2012 focusing on trends in incidence, mortality and prevalence among older patients.

Material and methods

Cancer of the colon was defined as ICD-10 code C18.9, rectal cancer as C20.9 and anal cancer as C21.0. A more detailed description of the materials and methods appear elsewhere [Citation6]. In brief, data were derived from the NORDCAN database with comparable data on cancer incidence, mortality, prevalence and relative survival in the Nordic countries, where the Danish data are delivered from the Danish Cancer Registry and the Danish Cause of Death Registry with follow-up for death or emigration until the end of 2013. This study focuses on the elderly population with age categorized as 0–69, 70–79, 80–89 and 90 + years.

For incidence and mortality, age group specific numbers and rates per 100 000 person years are shown in tables and graphs with calendar periods for time of diagnosis 1978–1982, 1988–1992, 1998–2002, 2003–2007, 2010, 2011 and 2012. Prevalence is defined as the number of cancer patients (including cured patients as well) with that specific diagnosis still alive and is shown in tables by the end of 1980, 1990, 2000, 2005, 2010, 2011 and 2012.

Sex- and age-specific one- and five-year relative survival proportion ratios were calculated for each of the diagnostic groups for the age groups 0–69, 70–79, 80–89 and 90 + years and for the five-year periods of diagnosis 1968–1972, 1973–1977, …, 2003–2007 and 2008–2012.

Relative survival for a group of cancer patients is calculated as the observed survival (where all causes of death are considered events) divided by the expected survival for a group from the Danish population with the same age and year of birth composition. Actuarial method is used for observed survival and Ederer II method for expected survival [Citation7]. Relative survival can be interpreted as the survival if the cancer was the only cause of death. For the most recent period, 2008–2012, not all patients can be followed up for death in five years and we used hybrid methods where we supplement with survival experience from cancer patients diagnosed earlier years. Survival was not calculated for cancer groups with less than five patients [indicated by (-) in tables and blank in the graphs]. If all patients die in the follow-up period resulting in zero survival this is indicated as 0 (-) and if calculation for a cell results in a relative survival higher than 100% the result is shown in tables, but restricted to 100% in graphs.

Results

Incidence

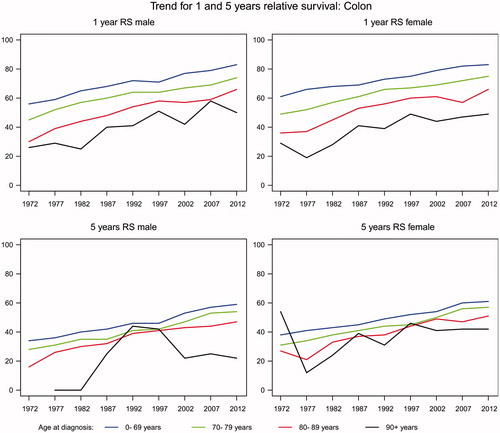

The incidence of colon cancer has increased by 62.7% from 1770 annual new cases in 1980 to 2880 new cases in 2012 (). The increase was highest for males with almost a doubling from 766 to 1386 cases, but the disease is still more frequent in women with a total 1494 of new cases in females in 2012. Between 1980 and 2012, the proportion of patients diagnosed with colon cancer after the age of 70 years remained stable at about 56% in men and 60% in women. show that the incidence rates are considerably higher in men and women aged more than 70 years compared with those aged less than 70 years. The rates have increased constantly over the period and the fluctuations seen for persons aged 90 years or more are likely to be due to a small number of patients ().

Figure 1. Incidence rates of colon cancer in Denmark, 1980–2012, by age group. A. Males, B. Females.

Table IA. Average annual number of new cases of colon cancer in Denmark.

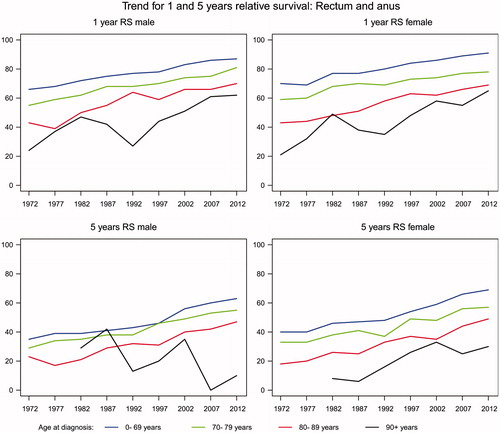

The incidence of cancer of the rectum and anus has increased by 28% from on average 1282 annual new cases in 1980 to 1642 in 2012 (). The proportion of patients diagnosed after the age of 70 years has decreased with time from about 54% in 1980 to 48% in 2012. While the incidence rates of cancer of the rectum and anus are still much higher in persons aged 70 years or more than in younger persons (), there seem to be a trend of decreasing rates with time among the elderly.

Figure 2. Incidence rates of cancer of the rectum and anus for male and female in Denmark, 1980–2012, by age group. A. Males, B. Females.

Table IB. Average annual number of new cases of cancer of the rectum and anus in Denmark.

Mortality

The average annual number of deaths from colon cancer increased by 9% from 1228 in 1980 to 1337 in 2012 () and 67–72% of these deaths occurred in patients aged 70 years or more. In patients older than 70 years the mortality has increased 14.5%. For females the mortality has decreased in all age groups among 0–84 years, but increased among 85–90 + years. The mortality of males has increased in all age groups except for 70–74 years.

Table IIA. Average annual number of deaths from colon cancer in Denmark.

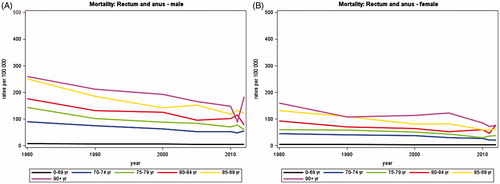

The rectal and anal cancer mortality has decreased from 755 average annual numbers of deaths in 1980 to 561 in 2012, a decrease of 25.7% (). This decrease is almost equally distributed among the two genders with 25.4% in males and 26.7% in females. Among females the decrease is larger in patients younger than 70 years, whereas the decrease is comparable in males younger and older than 70 years. In patients aged 90 + the mortality has increased in both genders.

Table IIB. Average annual number of deaths from cancer of the rectum and anus in Denmark.

The mortality rates of colon, rectal and anal cancer have decreased in all age groups and both genders ( and ). In colon cancer there is an overall decrease of 16.7% with the largest decrease seen in females in all age groups except for age group 70–74 years.

Figure 3. Mortality rates of colon cancer in Denmark, 1980–2012, by age group. A. Males, B. Females.

Figure 4. Mortality rates of cancer of the rectum and anus in Denmark, 1980–2012, by age group. A. Males, B. Females.

In rectal and anal cancer the decrease fluctuates throughout all age groups, but is almost equal among genders with 45.8% in males and 43.5% in females ().

Survival

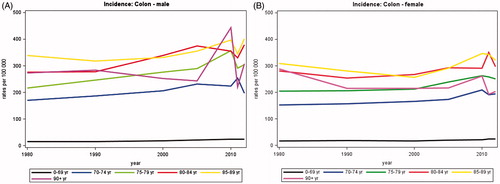

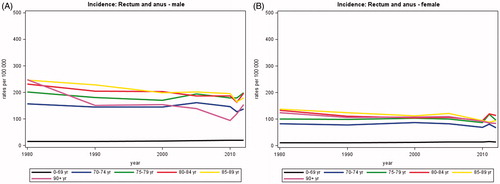

The one-year age-specific relative survival after a diagnosis of colon, rectal and anal cancer has increased in both genders and all age groups from 1968 to 2012 ( and ). In colon cancer it has increased mostly in males, with an average of 29% versus 24.5% in females. The increase is highest in both males and females aged 80–89.

In rectal and anal cancer the increase is similar in males (28%) and females (27.8%) with the highest increase in age group 90 + years in both genders.

The five-year age-specific relative survival after colon, rectal and anal cancer has also increased for both genders and in all age groups except for 90 + years female patients with colon cancer ( and ). In colon cancer the increase is higher in males (26%) than females (15%). In rectal and anal cancer the increase is higher in females (28.5%) than males (14.8%).

In the most recent period 2008–2012 both one- and five-year age-specific relative survival after colon, rectal and anal cancer is decreasing with increased age.

Prevalence

Prevalence of colon cancer has more than doubled from 7242 annual number of persons alive in Denmark by 31 December in 1980 to 18 400 persons in 2012 (). Today, 64% of men and 70% of women surviving colon cancer are over the age of 70 years and 4–9% are 90 years or older. Rectal and anal cancer prevalence has increased by 117% from 5565 persons alive in Denmark in 1980 to 12 071 persons in 2012 () of whom 58% were older than 70 years.

Table IIIA. Prevalence: Annual number of persons alive after colon cancer in Denmark by December 31.

Table IIIB. Prevalence: Annual number of persons alive after cancer of the rectum and anus in Denmark by December 31.

Discussion

The incidence of CRC has increased over the past decades, in both patients younger and older than 70 years. Incidence rate has increased in patients with colon cancer, but in patients with rectal and anal cancer a decreasing trend is found in the oldest age group. Sporadically screening 10–20 years ago may have eliminated pre-malignity resulting in a decreasing incidence rate among the oldest.

Mortality has diminished in younger patients with colon cancer, but has increased in patients >70 years and increased with increasing age. However, mortality has increased to a lesser extent than incidence. In rectal and anal cancer mortality has also decreased, except among the oldest patients. This correlates to a decreasing incidence rate. The one- and five-year age-specific relative survival after a diagnosis of colon, rectal or anal cancer has increased for both genders and in all age groups, but the survival is decreasing with increased age.

Data from the oldest age groups are influenced by large fluctuations in both genders probably due to the small amount of patients, which should be taken into account when analyzing the data. Furthermore, the analyzed data describes one large group regardless of stage. Thus, it is not possible to draw detailed conclusions about incidence, mortality and survival in the each stage, but only in CRC as a whole, focusing on gender and age.

Data on rectal and anal cancer is merged in the present material. Only adenocarcinoma will be discussed in the following.

Prolonged survival in patients with mCRC from 1980 to 2008 has been shown in a recent population-based study founded on the Nordic Cancer Registries [Citation8]. It showed both improved median- and long-term survival in the general population of patients with synchronous mCRC, however, most pronounced in patients younger than 60 years. These findings of increased incidence and survival may be due to an earlier diagnosis and improved surgery, pre- and postoperative oncological treatment and regularly checkups. Earlier diagnosis may involve stage migration which occurs when more intensive staging at initial cancer diagnosis may lead to a falsely increased survival as patients with occult metastatic disease are diagnosed earlier. For instance, clinically benign tumors of the rectum are now subjected to transanal ultrasound at advanced local en-block resection methods, which may lead to a higher number of early diagnosed rectal cancers.

The surgical techniques in the treatment of CRC have improved. In 1996, total mesorectal excision (TME) was implemented in Denmark as standard treatment in patients with rectal cancer, leading to an improved outcome primarily due to reduced local recurrence rate [Citation9]. Additionally self-expanding stents for treatment of cancer-related acute colo-rectal obstructions have been introduced, giving the opportunity to convert acute surgery into planned procedures, which is associated with prolonged survival [Citation10]. Furthermore, laparoscopic surgery is gaining ground and is found to reduce traumas significant and improve and accelerate the rehabilitation of patients after surgery. In addition, perioperative care has also improved and the access to better anesthesiology and intensive care has changed attitude of surgeons to be more aggressive especially in the older. Additionally, the hospital admissions are shortened, readmissions are fewer and the 30-day mortality after elective surgery has been reduced significantly in Denmark from 7.3% in 2001–2002 to 2.8% in 2011 [Citation11].

The evolution of chemotherapy and targeted therapy has also lead to increased survival. The backbone of medical treatment of mCRC is still 5-flourourcacil (FU), but in 2000 irinotecan and oxaliplatin were introduced in the standard therapy leading to increased efficacy with mOS approaching 24 months in selected patients included in clinical trials [Citation12]. Five years later, targeted agents with the anti-EGFR antibodies, cetuximab and panitumumab, and the anti-angiogenic agent bevacizumab were launched with further improvement in mOS [Citation12,Citation13].

Furthermore, increased use of chemotherapy may account for the increase in survival. The use of palliative chemotherapy has increased from approximately 20% to more than 60% from 1989 to 2006 in patients with mCRC aged <75 years old [Citation14,Citation15]. In the same period the use increased from 2% to 40% and from 2% to 25% in patients >75 years diagnosed with metastatic colon and rectal cancer respectively [Citation14,Citation15].

Finally, establishment of multidisciplinary teams, with participation of surgeons, pathologists, oncologists and radiologist which evaluate all patients with CRC has contributed to a better outcome [Citation16].

Prevalence is widely increased both because of the increased incidence and the better survival, which is reflected in the increasing one- and five-year age-specific relative survival. More patients will thus survive or live longer with a diagnosis of CRC, but with potentially late toxicities after multi-modality therapy [Citation17]. This raises an increased need of knowledge on late toxicities after surgery, radiotherapy and chemotherapy and for rehabilitation, which in Denmark is part of the recommendations in the third Danish Cancer Control plan from 2010 aiming to offer all patients focused rehabilitation.

Older patients with CRC

In most developed countries life expectancy has increased almost linear [Citation18] leading to a growing older population. This may explain the increasing incidence among older people shown in the present data.

Mortality among patients with colon cancer aged 0–74 years has decreased, whereas the mortality in patients >74 years has risen and continues to increase with advanced age.

Adjuvant combination chemotherapy with 5-FU and oxaliplatin after radical resection of colon cancer increases cure rate. Nevertheless, older patients are less likely to receive adjuvant chemotherapy. In a study from the Netherlands it was demonstrated that 79% of patients with colon cancer <75 years received chemotherapy in an adjuvant setting compared to only 19% of patients >75 years [Citation15]. However, efficacy of adjuvant chemotherapy in older patients is though disputed, as a recent study has shown that patients >70 years seemed to have a reduced benefit from oxaliplatin-based combination chemotherapy, but still retain efficiency when treated with oral fluoropyrimidines as monotherapy [Citation19].

The standard chemotherapy for younger fit mCRC patients includes doublet or triplet chemotherapy with or without targeted therapy [Citation20] resulting in an increase of survival. Among older patients this increase in survival has been delayed, properly due to a gradually and delayed introduction in older patients [Citation8]. Older fit patients included in clinical trials were found to tolerate combination chemotherapy and have the same benefit as younger patients [Citation21]. Targeted agents are used in the older population [Citation12] and it has been shown, that there was no significant difference in relative risk (RR) and safety profile between patients older or younger than 65 years for patients treated with cetuximab and irinotecan [Citation22]. Additionally, a randomized study, AVEX [Citation23], in older fit patients showed that addition of bevacizumab improved the efficacy of single agent capecitabine.

Nevertheless, a recent large community-based study [Citation24], demonstrated that older patients (>65 years) were less likely to receive first-line doublet chemotherapy and also less likely to receive irinotecan, oxaliplatin, and bevacizumab during the entire course of the disease. In this unselected group of patients, older patients had a shorter mOS (19.1 months vs. 24.5 months) and more toxicity-related hospitalizations (21% vs. 11%) than younger patients. Furthermore, a Scandinavian population-based study showed that 86% of younger patients (<66 years) with mCRC received palliative chemotherapy, while it was only the case in 40% of patients older than >75 years [Citation5]. In Sorbye et al.’s study, the mOS was only 10.7 months, even though the mOS in the subgroup of patients treated with combination chemotherapy in clinical trials was 21.3 months. The short mOS was primarily due to a very short survival in patients above 75 years of age and in patients not given any chemotherapy [Citation5].

It is also likely that the older patients will benefit more from the development in local resections of rectal cancers because mortality related to major surgery in the older patients is high.

Older cancer patients are under-represented in clinical trials [Citation4]. In clinical trials of patients with mCRC during the period 2001–2005 the median age was only 62 years, while the median age at diagnosis according to cancer registers was 71–74 years [Citation8]. Furthermore, older patients included in clinical trials are selected on basis of appropriate performance status and sufficient organ functions by means of strict exclusion criteria in the clinical trials. These patients are thus not representative of the majority of older patients who are treated in clinics every day and there is therefore limited knowledge on how to treat the older CRC patients. The discrepancy between the results from subgroup analyzes in randomized clinical trials and community-based studies is probably due to a higher proportion of patients with co-morbidities and poorer performance status in the unselected community-based study than in the randomized clinical trials.

Ageing causes a range of challenges due to age-related loss of function in several important organs (liver, kidney, lung, heart, bone marrow), more comorbidity, polypharmacy as well as mental and social support. These circumstances are individual from one older patient to another. Side effects will cause a different pattern than known from younger patients when treated with chemotherapy and targeted therapy. Thus older patients represent a complex heterogeneous group of patients who challenges the principles of optimal oncological and surgical procedures and the decision making ahead of surgery and the prescription of systemic therapy.

As patients with CRC often develop metastatic disease, management of mCRC in older patients is relevant. The benefit of the treatment given in a palliative setting must be compared to risk of adverse events due to toxicity and decreased quality of life [Citation25]. Thus focus is currently on how to individualize treatment strategies to older cancer patients, both through more clinical studies including frail older patients and finding the best marker/method to select older patients for chemotherapy and to predict efficacy and toxicity [Citation25].

Conclusion

The incidence of CRC has increased during the past 30 years, but mortality has decreased primarily in patients younger than 70 years. In patients older than 70 years the mortality has increased, but not equally to incidence. In both younger and older patients the relative survival has increased and thus prevalence has widely increased, leading to new challenges, i.e. rehabilitation and late toxicities.

The overall increase in survival is multifactorial and reflects earlier diagnosis, improved surgical techniques, pre- and postoperative oncological treatment and regularly checkups. The current demographic ageing leads to a rising amount of older patients. There is limited knowledge on how to treat unselected older CRC patients and future studies must explore how to select and tailor the treatment for older CRC patients.

Acknowledgements

We thank Niels Christensen and Anne Mette T. Kejs, Danish Cancer Society, Department of Documentation & Quality, for making the tabulations of incidence, mortality and prevalence, calculation of relative survival and trend graphs.

Declaration of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

References

- Ferlay J, Steliarova-Foucher E, Lortet-Tieulent J, Rosso S, Coebergh JW, Comber H, et al. Cancer incidence and mortality patterns in Europe: estimates for 40 countries in 2012. Eur J Cancer 2013;49: 1374–403.

- Johnson CM, Wei C, Ensor JE, Smolenski DJ, Amos CI, Levin B, et al. Meta-analyses of colorectal cancer risk factors. Cancer Cause Control 2013;24:1207–22.

- Kopetz S, Chang GJ, Overman MJ, Eng C, Sargent DJ, Larson DW, et al. Improved survival in metastatic colorectal cancer is associated with adoption of hepatic resection and improved chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol 2009;27:3677–83.

- Scher KS, Hurria A. Under-representation of older adults in cancer registration trials: known problem, little progress. J Clin Oncol 2012;30:2036–8.

- Sorbye H, Pfeiffer P, Cavalli-Bjorkman N, Qvortrup C, Holsen MH, Wentzel-Larsen T, et al. Clinical trial enrollment, patient characteristics, and survival differences in prospectively registered metastatic colorectal cancer patients. Cancer 2009;115:4679–87.

- Ewertz M, Christensen K, Engholm G, Hansen O, Kejs AMT, Lund L, et al. Trends in cancer in the elderly population in Denmark, 1980-2012. Acta Oncol 2015; doi: 10.3109/0284186X.2015.1114678.

- Dickman PW, Sloggett A, Hills M, Hakulinen T. Regression models for relative survival. Stat Med 2004;23:51–64.

- Sorbye H, Cvancarova M, Qvortrup C, Pfeiffer P, Glimelius B. Age-dependent improvement in median and long-term survival in unselected population-based Nordic registries of patients with synchronous metastatic colorectal cancer. Ann Oncol 2013;24:2354–60.

- Kapiteijn E, Putter H, van de Velde CJ. Impact of the introduction and training of total mesorectal excision on recurrence and survival in rectal cancer in The Netherlands. Br J Surg 2002;89:1142–9.

- Iversen LH, Kratmann M, Boje M, Laurberg S. Self-expanding metallic stents as bridge to surgery in obstructing colorectal cancer. Br J Surg 2011;98:275–81.

- Iversen LH, Ingeholm P, Gogenur I, Laurberg S. Major reduction in 30-day mortality after elective colorectal cancer surgery: a nationwide population-based study in Denmark 2001-2011. Ann Surg Oncol 2014;21:2267–73.

- Pfeiffer P, Qvortrup C, Bjerregaard JK. Current status of treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer with special reference to cetuximab and elderly patients. Onco Targets Ther 2009;2:17–27.

- Van Cutsem E, Cervantes A, Nordlinger B, Arnold D. Metastatic colorectal cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-updagger. Ann of Oncol Epub 2014;25(Suppl 3):iii1-9.

- Elferink MA, van Steenbergen LN, Krijnen P, Lemmens VE, Rutten HJ, Marijnen CA, et al. Marked improvements in survival of patients with rectal cancer in the Netherlands following changes in therapy, 1989-2006. Eur J Cancer 2010;46:1421–9.

- Van Steenbergen LN, Elferink MA, Krijnen P, Lemmens VE, Siesling S, Rutten HJ, et al. Improved survival of colon cancer due to improved treatment and detection: a nationwide population-based study in The Netherlands 1989-2006. Ann Oncol 2010;21: 2206–12.

- Adam R, Haller DG, Poston G, Raoul JL, Spano JP, Tabernero J, et al. Toward optimized front-line therapeutic strategies in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer–an expert review from the International Congress on Anti-Cancer Treatment (ICACT) 2009. Ann Oncol 2010;21:1579–84.

- Braendengen M, Tveit KM, Bruheim K, Cvancarova M, Berglund A, Glimelius B. Late patient-reported toxicity after preoperative radiotherapy or chemoradiotherapy in nonresectable rectal cancer: results from a randomized Phase III study. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2011;81:1017–24.

- Christensen K, Doblhammer G, Rau R, Vaupel JW. Ageing populations: the challenges ahead. Lancet 2009;374:1196–208.

- Mccleary NJ, Meyerhardt JA, Green E, Yothers G, de Gramont A, Van Cutsem E, et al. Impact of age on the efficacy of newer adjuvant therapies in patients with stage II/III colon cancer: findings from the ACCENT database. J Clin Oncol 2013;31:2600–6.

- Schmoll HJ, Van Cutsem E, Stein A, Valentini V, Glimelius B, Haustermans K, et al. ESMO Consensus Guidelines for management of patients with colon and rectal cancer. a personalized approach to clinical decision making. Ann Oncol 2012;23:2479–516.

- Sanoff HK, Bleiberg H, Goldberg RM. Managing older patients with colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol 2007;25:1891–7.

- Jehn CF, Boning L, Kroning H, Pezzutto A, Luftner D. Influence of comorbidity, age and performance status on treatment efficacy and safety of cetuximab plus irinotecan in irinotecan-refractory elderly patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. Eur J Cancer 2014;50: 1269–75.

- Cunningham D, Lang I, Marcuello E, Lorusso V, Ocvirk J, Shin DB, et al. Bevacizumab plus capecitabine versus capecitabine alone in elderly patients with previously untreated metastatic colorectal cancer (AVEX): an open-label, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2013;14:1077–85.

- Mckibbin T, Frei CR, Greene RE, Kwan P, Simon J, Koeller JM. Disparities in the use of chemotherapy and monoclonal antibody therapy for elderly advanced colorectal cancer patients in the community oncology setting. Oncologist 2008;13:876–85.

- Mccleary NJ, Dotan E, Browner I. Refining the Chemotherapy Approach for Older Patients With Colon Cancer. J Clin Oncol 2014;32:2570–80.