Abstract

Background The improved survival after breast cancer has prompted knowledge on the effect of a breast cancer diagnosis on health-related quality of life (HQoL). This study compared changes in HQoL among women from before to after breast cancer diagnosis with longitudinal changes among women who remained breast cancer-free.

Material and methods The Danish Diet, Cancer and Health study included 57 053 cancer-free persons aged 50–64 years at baseline (1993–1997). We used data from first follow-up (1999–2002) and second follow-up (2010–2012) on HQoL [Medical Outcomes Survey, short form (SF-36)] obtained from 542 women aged 64–82 years with primary breast cancer (stages I–III) and a randomly matched sample of 729 women who remained breast cancer-free. Linear regression models were used to estimate the differences in changes in HQoL between women with and without breast cancer; the analyses were repeated with stratification according to age, comorbidity, partner support and time since diagnosis.

Results Women with breast cancer reported significantly larger decreases in HQoL from before to after diagnosis than those who remained breast cancer-free (physical component summary, −2.0; 95% CI −2.8; −1.2, mental component summary, −1.5, 95% CI −2.3; −0.6). This association was significantly modified by comorbidity and time since diagnosis.

Conclusions Women with breast cancer reported significantly larger HQoL declines than breast cancer-free women. Breast cancer diagnosis seems to have the greatest impact on HQoL closest to diagnosis and in women with comorbidity indicating that this group should be offered timely and appropriate follow-up care to prevent HQoL declines.

An increasing number of breast cancer survivors live beyond treatment and may experience physical and mental consequences of disease and treatment that affect their health-related quality of life (HQoL) [Citation1–3]. Comorbidity, which is common in women over the age of 60 [Citation4], and social support may however, also play important roles and interact with the impact of a breast cancer diagnosis on HQoL [Citation5–8].

The Medical Outcomes Study, short form (SF-36) has often been used to evaluate changes in HQoL attributable to breast cancer from general changes in HQoL over time when compared with cancer-free controls [Citation9–12] and studies have suggested long lasting negative effects on HQoL [Citation9,Citation10], even when adjusted for comorbidity [Citation10]. The negative effects of breast cancer seem to decrease with time, and HQoL may reach the level of breast cancer-free controls 5–10 years after diagnosis [Citation10–12]. None of these studies, however, included information on pre-illness levels of HQoL that may influence post-diagnosis HQoL [Citation4,Citation8].

To our knowledge, only two prospective studies of sufficient size (n > 20) have compared changes in HQoL assessed with the SF-36 among women with and without breast cancer and confirmed greater declines in HQoL among women with breast cancer [Citation13,Citation14]. Both studies are, however, prone to potential lack of generalizability due to inclusion of nurses only, who per se know more about disease and treatment and how to navigate the healthcare system, which may positively influence HQoL [Citation13,Citation14]. In addition, the studies used self-reported information on comorbidity, which may be subject to recall and information bias. Thus, we still need knowledge of the consequences of breast cancer on HQoL from large prospective and population-based studies taking pre-illness levels of HQoL into account.

In this prospective study based on data from the Diet, Cancer and Health (DCH) study and registry data on cancer and comorbidity, we had the unique opportunity to compare longitudinal changes in HQoL in middle-aged to elderly women with and without breast cancer after adjustment for potential confounding factors. We hypothesized that women would report larger decreases in HQoL from before to after a breast cancer diagnosis than women who remained breast cancer-free. Further, we examined differences in changes in HQoL by breast cancer status according to age, comorbidity, partner support and time since diagnosis. We expected greater decreases after breast cancer with increasing age due to age-related physical decline, in women with comorbid conditions, in women without partner support and in women closer to diagnosis.

Material and methods

The Diet, Cancer and Health study

We used prospective questionnaire data completed for the DCH study, which has been described in detail elsewhere [Citation15]. Briefly, between 1993 and 1997, 57 053 cancer-free persons aged 50–64 years filled out a baseline questionnaire (response rate, 37%). We used data on women from the first follow-up (1999–2002) as well as from the second follow-up (2010–2011), inviting all first follow-up participants (excluding women who had emigrated, died or did not wish to be contacted again) in whom breast cancer had been diagnosed as a first cancer after the first follow-up (n = 995) and a random sample of breast cancer-free women matched in five-year age intervals (n = 1401). The second follow-up questionnaire was returned by 67% (n = 662) of women with breast cancer and 61% (n= 861) of those without breast cancer.

Health-related quality of life

HQoL was measured with the SF-36 (version 2) [Citation16] at the first and second follow-up assessments. The SF-36 is a well validated, generic instrument for measuring eight domains of HQoL: physical functioning, role-physical, bodily pain, vitality, social functioning, role-emotional, mental health and general health. Each subscale is scored from 0 (poorest health) to 100 (best health) [Citation16]. The global physical and mental summary components are calculated from all eight subscales. Mean scores on the two summary scales and the eight subscales were computed by the ‘full missing data estimation’ procedure, allowing estimation of scale scores from a minimum of one answer per scale [Citation16]. Differences of 2–3 points on the norm-based physical component summary scale and three points on the mental component summary scale were suggested in previous reports to represent minimally important clinical differences between group means [Citation16].

Demographic characteristics

We obtained information on education length (≤7, 8–10, >10 years) from the DCH baseline questionnaire and date of diagnosis from the Danish Cancer Registry [Citation17] or the Danish Pathology Registry [Citation18] depending on the date of tissue retrieval.

Clinical and treatment characteristics

Information on disease and treatment including disease stage (I–III), tumor size (≤20, >20 mm), number of lymph nodes with metastases (0, ≥1), type of surgery (mastectomy, lumpectomy), radiation therapy (yes, no), chemotherapy (yes, no) and endocrine treatment (yes, no) was retrieved from the Danish Breast Cancer Cooperative Group, which holds information on approximately 95% of Danish women under 75 years with breast cancer [Citation19].

Comorbidity

To assess physical comorbidity, data on hospital admissions and outpatient contacts (registered since 1977 and 1995, respectively) were obtained from the Danish National Patient Register [Citation20]. The Charlson comorbidity index (CCI) [Citation21] was calculated from the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-7 and ICD-10 codes), registered for each woman between 1977 and first follow-up. The CCI was designed to estimate the risk for death due to a comorbid condition in survival studies and comprises 19 conditions, ranging from heart disease, diabetes to cancer and AIDS, which are assigned values of 1–6 according to their association with mortality. We excluded cancer diagnoses and categorized comorbidity as 0, 1 or ≥2 at first follow-up.

Partner support

Social support, defined as the individuals’ perception of how often they could talk to their spouses or partners when they needed it (‘always’, ‘often’, ‘now and then’, ‘rarely’, ‘never’ and ‘have none’), was measured from responses to a single item at the first follow-up and categorized into ‘high partner support’ (combining the original response categories ‘always’, ‘often’), ‘low partner support’ (‘now and then’, ‘rarely’, ‘never’) and ‘no partner’. The item was part of a social support questionnaire, which has previously been shown to be valid and have fair-to-excellent eight-day test–retest agreement but which does not yield a summary score [Citation22].

Study sample

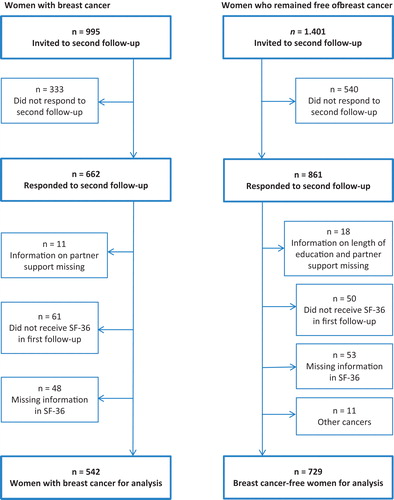

Of the 662 women with and 861 without breast cancer who responded to the second follow-up questionnaire, we excluded women with missing information on education (n = 1), partner support (n = 28), HQoL at the first or second follow-up (n = 101) and women who had another cancer beside the breast cancer (n = 11), or who did not receive the SF-36 scale in the first follow-up questionnaire (n = 111), leaving 1271 women for the analyses. Breast cancer was diagnosed in 542 of these women between the first and second follow-up and 729 women remained cancer-free ().

Statistical analysis

Descriptive analyses (χ2- and t-tests) were conducted of differences in sociodemographic and clinical characteristics and mean HQoL on each of the eight subscales and the two component summaries between the 542 women with breast cancer and the 729 who remained breast cancer-free ().

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of 542 women with breast cancer and 729 women who remained breast cancer-free.

For each of the eight subscales and the two summary scales, a linear regression model was used to estimate the association between a breast cancer diagnosis and the change in HQoL score from first to second follow-up. The mean differences in change scores (with 95% CIs) between women with breast cancer and matched controls were estimated after adjustment for age at first follow-up (continuous), education at baseline (≤7, 8–10, >10 years), comorbidity (0, 1, ≥2), partner support (no, low, high) and score at first follow-up for the given HQoL scale score (continuous), all considered potential confounders of the association. The assumption of normal distribution of change scores was confirmed from Q-Q plots, while the assumption of linearity of the association with the continuous variables (score value and age at first follow-up) was tested by adding quadratic terms to the model. For age at first follow-up, no deviations from linearity were observed (smallest p > 0.13); whereas the quadratic term of the score value for the two subscales role-physical and role-emotional at first follow-up added significantly (p = 0.0004 and p < 0.0001, respectively) to the model; therefore, adjustment including a quadratic term was made ().

Table 2. Mean changes between first (fu1) and second (fu2) follow-up and differences in changes in health-related quality of life with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) among women with a diagnosis of breast cancer (n = 542) and women who remained breast cancer-free (n = 729) between the first and second follow-up.

To investigate whether the association between breast cancer status and change in HQoL differed by age (≤60, >60 years), comorbidity (0, ≥1), partner support (no/low, high) and time since diagnosis (≤5, >5 years), we added an interaction term between breast cancer status and each of the four potential modifiers, one at a time. The mean change differences in HQoL by these variables were estimated, and effect modification was tested using F tests ().

Table 3. Differences in changes in health-related quality of life for 542 women with breast cancer and 729 who remained free of breast cancer, stratified by age, comorbidity, partner support and time since diagnosis (n = 1271).

We compared participants who did not respond to the second follow-up questionnaire or for whom information was missing (453 women with breast cancer, 672 without) with those who responded to all questionnaires (breast cancer n = 542, breast cancer-free n = 729) on age, education, comorbidity, partner support, clinical and treatment characteristics and SF-36 mean component summary scores, using a χ2-test for categorical and a t-test for continuous variables. The SAS statistical software package release 9.3 was used for the analyses.

Results

Irrespective of a breast cancer diagnosis, all women experienced decreases in HQoL between the first and second follow-up. Women diagnosed with breast cancer had significantly lower mean HQoL scores in physical and role-physical functioning and more comorbidity at first follow-up than women who remained breast cancer-free (). Significantly larger decreases in HQoL were found among women diagnosed with breast cancer than among those who remained breast cancer-free in the physical component summary (−2.0; 95% CI −2.8; −1.2), the mental component summary (−1.5; 95% CI −2.3; −0.6) and the subscales physical functioning (−2.2; 95% CI −4.0; −0.4), role-physical (−3.0; 95% CI −5.4; −0.6), vitality (−3.0; 95% CI −4.9; −1.1), role-emotional (−2.8; 95% CI −5.0; −0.6) and general health (−2.1; 95% CI −4.0; −0.2) ().

Significantly larger decreases in HQoL for women with breast cancer relative to those who remained breast cancer-free were seen among women with comorbidity [physical component summary (−4.1; 95% CI −6.0; −2.2 vs. −1.6; 95% CI −2.4; −0.7), general health (−7.9; 95% CI −12.0; −3.5 vs. −1.1; 95% CI −3.1; 1.0)] and for women closer to the time of diagnosis (≤5 years) rather than further from diagnosis (>5 years) ().

Even though age and partner support at first follow-up did not significantly modify the effect of a breast cancer diagnosis on all HQoL scales, greater decreases were seen in the physical component summary for women aged >60 years and for women with high partner support, while greater declines in the mental component summary were observed in women aged ≤60 years and among women with high partner support ().

Participants independent of breast cancer status who responded only to the baseline and first follow-up questionnaires or for whom information was missing were significantly younger, had shorter education, more comorbidity and lower scores on the physical and mental component summary scales than participants who responded to all questionnaires (Supplementary information S1 and S2, available online at http://www.informahealthcare.com).

Discussion

In this large population-based study, women with breast cancer reported greater decreases in HQoL from before to after breast cancer diagnosis than women who remained breast cancer-free. Significantly, larger decreases in HQoL for women with breast cancer relative to women who remained breast cancer-free were found closest to time of diagnosis and in women with comorbidity.

Our results support the previous two larger prospective studies reporting greater decreases in HQoL for breast cancer survivors than for breast cancer-free women [Citation13,Citation14]. Michael et al. estimated the relative risk for decreased functional health among women with and without breast cancer and found persistent declines in multiple dimensions of functional health status after breast cancer [Citation14]. Kroenke et al. estimated mean changes in SF-36 scores and report results directly comparable with ours [Citation13]. They found slightly larger decreases in HQoL among 226 elderly women with breast cancer than in an age-appropriate comparison group within the first five years after diagnosis compared to our findings in: role-physical, −7.5 versus −5.2; bodily pain, −2.7 versus −2.6; social functioning, −4.4 versus −3.3; and role-emotional, −5.5 versus −4.3. These slightly larger differences may reflect that their study population was closer to diagnosis than our population. The mean time between diagnosis and follow-up was five years (range 0.5–10.0 years) in our study and 2.1 years in the study by Kroenke et al. Previous studies have shown [Citation10–12] that differences in decreases in HQoL wane over time and we also found the strongest association between breast cancer and decreases in HQoL within the first five years of diagnosis ().

Although we found significantly larger differences in changes in both the physical and the mental health component summary among women with breast cancer compared with breast cancer-free women, the declines were modest and only in the physical component summary the differences between group means reached the lower level of the suggested minimally important clinical difference [Citation16] (). Limitations in physical and mental function after breast cancer are likely related to the breast cancer disease, but especially to the treatment including surgery, chemotherapy and for some radiotherapy causing upper limb morbidities and pain, swelling of the arm, sensory disturbances, fatigue, cognitive impairment, anxiety, depression, changed body image, and sexual problems [Citation23]. Most women in our study, however, were diagnosed at an early disease stage and received less aggressive treatment (57% of the women were treated with breast conserving therapy, 11% received chemotherapy and 57% received endocrine treatment) (), which may have contributed to the moderate HQoL declines observed in our study [Citation12,Citation24,Citation25].

Concerning the physical declines, we found that all women irrespective of breast cancer status reported declines in HQoL physical function over time. This indicates that the observed declines in physical function are partly related to physical changes and perhaps minor morbidities occurring with increasing age. Comorbidity may in itself influence HQoL due to the unique physical impact of the specific health condition and may thus play an important role for the association between breast cancer and HQoL [Citation4,Citation7,Citation8]. We observed a significantly higher prevalence of comorbidity among women with breast cancer before diagnosis (). The presence of comorbidity before breast cancer diagnosis may already have caused decrements in HQoL and continue to impact HQoL during the breast cancer trajectory, as it may exacerbate breast cancer symptoms, influence the types of cancer treatments offered, the success of treatment, and the recovery over time [Citation4]. Our study confirmed a significant effect of comorbidity on the association between breast cancer and HQoL and we observed significantly larger decreases in the physical component summary according to breast cancer status, which is also in agreement with previous studies [Citation4,Citation7,Citation8] ().

Although age and partner support did not modify the effect of a breast cancer diagnosis on physical functioning, we found moderate, larger decreases in the physical component summary according to breast cancer status among women over 60 years than those who were 60 years or younger and among women with high partner support than those with no/low partner support (). The slightly stronger association with older age is in line with previous research [Citation8,Citation13,Citation25] and may suggest residual confounding from comorbidity or poorer biological ability to compensate for the adverse effects of cancer treatment. With regard to the slightly larger decreases observed in physical functioning according to breast cancer status among women with high partner support, we have no immediate explanation and further investigation is warranted.

Only minor declines in mental HQoL were observed and the advanced age (median 66 years) at time of diagnosis of our population may play an important role. Previous studies have shown that while older women with breast cancer may experience greater declines in physical functioning, they tend to report better mental functioning when compared with younger women with breast cancer [Citation8,Citation13,Citation26]. The differences in mental health declines among younger versus older women are suggested to be related to the greater impact of a breast cancer diagnosis in younger women in areas of educational, career and family plans, including raising children [Citation26]. Supporting previous study findings [Citation8,Citation13,Citation26], we observed a similar trend and found a slightly stronger, but non-significant association between breast cancer status and declines in the mental health component summary among younger (≤60 years) women.

Comorbidity and partner support did not modify the association between breast cancer and mental HQoL. However, we found slightly larger decreases in the mental component summary according to breast cancer status among women with comorbidity compared to those without and among women with high partner support than those with no/low partner support (). In line with a previous study among breast cancer patients, this suggests that chronic disease burden is primarily associated with deficits in physical functioning and not highly correlated to emotional domains [Citation4]. Contrary to previous studies [Citation5,Citation6,Citation12] our study indicates that women with breast cancer who have no or unsupportive partners are not at a particular disadvantage when compared with women with a partner who provides reliable emotional support. An explanation might be that we measured social support only in relation to the emotional support provided by a partner when needed. Women tend to possess extensive and robust social networks [Citation6], but we did not include support from family and friends, which has shown to help decrease the negative effects of symptoms on HQoL [Citation27]. It could also be speculated, that although women perceive support from a partner to be highly available, they may engage in protective buffering, i.e. protect their partner from their cancer worries and concerns, which has been linked to increased distress among patients in satisfactory relationships [Citation28].

This study adds to the existing knowledge by describing prospective changes in the HQoL of women with and without breast cancer in a large population-based sample. The strengths of the study include its prospective design with the evaluation of changes in HQoL from before to after a breast cancer diagnosis in a random sample of the Danish population. Inclusion of an age-appropriate comparison group of breast cancer-free women enabled us to take into account life-stage physical functioning and mental health in evaluating the impact of breast cancer and its treatment on HQoL. Further, we used the SF-36, which is a well validated, non-disease-specific measure for assessing HQoL [Citation16]. To our knowledge, this is the first study to use unbiased registry-based data collected independently of the hypothesis under study on breast cancer characteristics and comorbidity, thus avoiding information and recall bias.

Excluding women with missing information on HQoL items could result in bias, as persons who do not provide full item scores may differ from responders in important ways [Citation16] and we thus used the ‘full missing data estimation’ procedure to minimize this bias. The CCI does not include psychiatric disorders and this may introduce misclassification, but as hospitalization for affective disorders, schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders is rare (2–3% of the general population), we expect that exclusion of psychiatric disorders affected the results minimally [Citation29]. Finally, the item on social support showed good face validity in a qualitative study [Citation22], but was confined to the perceived availability of good conversations with spouses or partners and has not been validated against other social support measures. This limits conclusions that can be drawn about the importance of social support and confines them to this particular function and source of support.

The participants in the DCH cohort comprised only one third of those invited and differed from the general population in terms of sociodemographic factors, health consciousness, use of the healthcare system [Citation25] and overall mortality [Citation30]. In addition, the participants in the current study responded to a second follow-up questionnaire and attrition analyses showed that women who were excluded were significantly younger, had shorter education, less partner support and lower HQoL. The healthy condition of the participants in this study might have attenuated the effect of breast cancer diagnosis on HQoL, however, we have no reason to believe that this would have affected the internal validity of our study findings. Still, the absolute estimated effects found in cohort studies should be generalized with caution.

Conclusions

Women with breast cancer had significantly greater, but modest decreases in HQoL compared to those who remained breast cancer-free. Stronger associations between breast cancer status, physical functioning and general health perception were seen among women with comorbid conditions. Also, the strongest association between breast cancer status and decreased HQoL was seen within the first five years of diagnosis. Based on this study, the message to cancer clinicians is that middle-aged and elderly women with breast cancer do experience larger decreases in HQoL than breast cancer-free women of the same age. Especially, women with breast cancer and other chronic conditions might require more intensive follow-up care to prevent decreases in physical function.

Ethical approval

The DCH study was approved by the regional ethical committees on human studies in Copenhagen and Aarhus and by the Danish Data Protection Agency.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and the writing of the paper. This study was funded by the Danish Cancer Society. We thank Katja Boll for Technical support.

References

- Cancer Facts & Figures. American Cancer Society 2011. Available from: http://www.cancer.org/acs/groups/content/@epidemiologysurveilance/documents/document/acspc-029771.pdf

- Jensen AR, Madsen AH, Overgaard J. Trends in breast cancer during three decades in Denmark: stage at diagnosis, surgical management and survival. Acta Oncol 2008;47:537–44.

- Cancerregisteret 2010. SST 2010Available from: URL: http://www.sst.dk/publ/Publ2011/DAF/Cancer/Cancerregisteret2010.pdf

- Deshpande AD, Sefko JA, Jeffe DB, Schootman M. The association between chronic disease burden and quality of life among breast cancer survivors in Missouri. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2011;129:877–86.

- Michael YL, Berkman LF, Colditz GA, Holmes MD, Kawachi I. Social networks and health-related quality of life in breast cancer survivors: a prospective study. J Psychosom Res 2002;52:285–93.

- Leung J, Pachana NA, McLaughlin D. Social support and health-related quality of life in women with breast cancer: a longitudinal study. Psycho Oncol 2014;23:1014–20.

- Smith AW, Reeve BB, Bellizzi KM, Harlan LC, Klabunde CN, Amsellem M, et al. Cancer, comorbidities, and health-related quality of life of older adults. Health Care Financ Rev 2008;29:41–56.

- Schoormans D, Czene K, Hall P, Brandberg Y. The impact of co-morbidity on health-related quality of life in breast cancer survivors and controls. Acta Oncol 2015;54:727–34.

- Helgeson VS, Tomich PL. Surviving cancer: a comparison of 5-year disease-free breast cancer survivors with healthy women. Psychooncology 2005;14:307–17.

- Klein D, Mercier M, Abeilard E, Puyraveau M, Danzon A, Dalstein V, et al. Long-term quality of life after breast cancer: a French registry-based controlled study. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2011;129:125–34.

- Hsu T, Ennis M, Hood N, Graham M, Goodwin PJ. Quality of life in long-term breast cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol 2013;31:3540–8.

- Peuckmann V, Ekholm O, Rasmussen NK, Moller S, Groenvold M, Christiansen P, et al. Health-related quality of life in long-term breast cancer survivors: nationwide survey in Denmark. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2007;104:39–46.

- Kroenke CH, Rosner B, Chen WY, Kawachi I, Colditz GA, Holmes MD. Functional impact of breast cancer by age at diagnosis. J Clin Oncol 2004;22:1849–56.

- Michael YL, Kawachi I, Berkman LF, Holmes MD, Colditz GA. The persistent impact of breast carcinoma on functional health status: prospective evidence from the Nurses' Health Study. Cancer 2000;89:2176–86.

- Tjonneland A, Olsen A, Boll K, Stripp C, Christensen J, Engholm G, et al. Study design, exposure variables, and socioeconomic determinants of participation in Diet, Cancer and Health: a population-based prospective cohort study of 57,053 men and women in Denmark. Scand J Public Health 2007;35:432–41.

- Ware JE, Jr, Kosinski M, Bjorner JB, Turner-Bowker DM, Gandek B, Maruish ME. User's Manual for the SF-36v2® Health Survey. 2nd ed. Lincoln, RI: QualityMetric Incorporated; 2007.

- Gjerstorff ML. The Danish Cancer Registry. Scand J Public Health 2011;39:42–5.

- Bjerregaard B, Larsen OB. The Danish Pathology Register. Scand J Public Health 2011;39:72–4.

- Moller S, Jensen MB, Ejlertsen B, Bjerre KD, Larsen M, Hansen HB, et al. The clinical database and the treatment guidelines of the Danish Breast Cancer Cooperative Group (DBCG); its 30-years experience and future promise. Acta Oncol 2008;47:506–24.

- Lynge E, Sandegaard JL, Rebolj M. The Danish National Patient Register. Scand J Public Health 2011;39:30–3.

- Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis 1987;40:373–83.

- Lund R, Nielsen LS, Henriksen PW, Schmidt L, Avlund K, Christensen U. Content validity and reliability of the Copenhagen social relations questionnaire. J Aging Health 2014;26:128–50.

- Ewertz M, Jensen AB. Late effects of breast cancer treatment and potentials for rehabilitation. Acta Oncol 2011;50:187–93.

- Arndt V, Stegmaier C, Ziegler H, Brenner H. Quality of life over 5 years in women with breast cancer after breast-conserving therapy versus mastectomy: a population-based study. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 2008;134:1311–18.

- Fehlauer F, Tribius S, Mehnert A, Rades D. Health-related quality of life in long term breast cancer survivors treated with breast conserving therapy: impact of age at therapy. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2005;92:217–22.

- Ganz PA, Desmond KA, Leedham B, Rowland JH, Meyerowitz BE, Belin TR. Quality of life in long-term, disease-free survivors of breast cancer: a follow-up study. J Natl Cancer Inst 2002;94:39–49.

- Manning-Walsh J. Social support as a mediator between symptom distress and quality of life in women with breast cancer. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs 2005;34:482–93.

- Manne SL, Norton TR, Ostroff JS, Winkel G, Fox K, Grana G. Protective buffering and psychological distress among couples coping with breast cancer: The moderating role of relationship satisfaction. J Fam Psychol 2007;21:380–8.

- Dalton SO, Steding-Jessen M, Gislum M, Frederiksen K, Engholm G, Schuz J. Social inequality and incidence of and survival from cancer in a population-based study in Denmark, 1994-2003: Background, aims, material and methods. Eur J Cancer 2008;44:1938–49.

- Larsen SB, Dalton SO, Schuz J, Christensen J, Overvad K, Tjonneland A, et al. Mortality among participants and non-participants in a prospective cohort study. Eur J Epidemiol 2012;27:837–45.