Abstract

Background: Several studies have documented an association between socioeconomic position and survival from gynaecological cancer, but the mechanisms are unclear. Objective: The aim of this study was to examine the association between level of education and survival after endometrial cancer among Danish women; and whether differences in stage at diagnosis and comorbidity contribute to the educational differences in survival. Methods: Women with endometrial cancer diagnosed between 2005 and 2009 were identified in the Danish Gynaecological Cancer Database, with information on clinical characteristics, surgery, body mass index (BMI) and smoking status. Information on highest attained education, cohabitation and comorbidity was obtained from nationwide administrative registries. Logistic regression models were used to determine the association between level of education and cancer stage and Cox proportional hazards model for analyses of overall survival. Results: Of the 3638 patients identified during the study period, 787 had died by the end of 2011. The group of patients with short education had a higher odds ratio (OR) for advanced stage at diagnosis, but this was not statistically significant (adjusted OR 1.20; 95% CI 0.97–1.49). The age-adjusted hazard ratio (HR) for dying of patients with short education was 1.47 (CI 95% 1.17–1.80). Adjustment for cohabitation status, BMI, smoking and comorbidity did not change HRs, but further adjustment for cancer stage yielded a HR of 1.36 (1.11–1.67). Conclusion: Early detection in all educational groups might reduce social inequalities in survival, however, the unexplained increased risk for death after adjustment for prognostic factors, warrants increased attention to patients with short education in all age groups throughout treatment and rehabilitation.

Several studies have documented associations between socioeconomic position and cancer outcomes [Citation1,Citation2]. Although the Danish tax-financed health system offers all citizens free access to health care, social inequality in survival after cancers at several sites has been shown [Citation3,Citation4]. The mechanisms by which socioeconomic position influences cancer survival must be understood so that targeted interventions can be designed.

Endometrial cancer is the sixth commonest cancer among Danish women, with a yearly incidence of 60 per 100 000, corresponding to about 750 cases diagnosed each year. The number has been increasing due to the ageing of the population [Citation4]. The association between socioeconomic position and endometrial cancer outcomes has been investigated in a few studies, and social inequality in incidence has been observed [Citation5–8]. Two nationwide register-based studies conducted in Denmark and Sweden found decreased mortality with increasing level of education after adjustment for age and period of diagnosis, but neither study included information on stage or treatment [Citation5,Citation6]. In two studies in the USA showing disparities in survival after endometrial cancer, area-based measures of socioeconomic position or race were used as proxies for socioeconomic position [Citation7,Citation8]. Patients with lower socioeconomic position might tend to ignore early symptoms of disease, experience delay in referral for specialist care, have more comorbidity or have an unhealthier lifestyle [Citation2]. These factors might influence the timing of a cancer diagnosis or affect its prognosis and thereby mediate the association between socioeconomic position and survival after endometrial cancer.

The aim of this register-based study was to determine whether socioeconomic position, measured by level of education, is associated with survival after endometrial cancer among Danish women and whether differences in stage at diagnosis, comorbidity, smoking and body mass index (BMI) explain any social differences in survival.

Material

Study population

Women born between 1920 and 1980 with endometrial cancer diagnosed in 2005–2009 were identified in the Danish Gynaecological Cancer Database (DGCD), with information on date of treatment plan (in this study defined as date of diagnosis), cancer characteristics, BMI and smoking status at the time of diagnosis. The DGCD was established in 2005 and covers 96% of all gynaecological cancers in Denmark [Citation9]. Of the 3655 cases identified, we excluded five who had migrated to or from Denmark during the two years before cancer diagnosis and 12 patients with no recorded information about education. The study population thus consisted of 3638 patients.

Cancer characteristics and treatment

Staging was carried out according to the recommendations of the Fédération Internationale des Gynécologistes et Obstétristes (FIGO). Cancer stage was divided into early stage (stages I + II), in which the cancer is limited to the corpus uterus, and advanced stage (stages III + IV), in which the cancer has either invaded other tissues or has metastasised [Citation9].

Treatment for endometrial cancer consists of surgery, surgery and supplementary chemotherapy or palliative treatment for advanced-stage (IV) disease, when recovery is not an option. As information on oncological treatment in the DGCD was insufficient, this variable could not be included in the final analysis.

Socioeconomic indicators

Data on highest attained education and cohabitation status were retrieved by linking the study population to the social registers in Statistics Denmark by means of the unique 10-digit personal identification number that is assigned to all residents of Denmark [Citation10–12]. We used information on educational level and cohabitation status two years before the endometrial cancer diagnosis to reduce any effects of early disease symptoms on these social factors. Highest attained education was categorised into short (mandatory education for seven and nine years for patients born before and after 1 January 1958, respectively), medium (between 8–10 and 12 years, i.e. youth education and vocational education) and higher education (>12 years).

Cohabiting was defined as two people of the opposite sex, over the age of 16 years with a maximum of 15 years difference in age, living at the same address with no other adult in residence, in the absence of marriage. Cohabitation status was categorised as living with a partner (married or cohabiting) or without a partner (single, widowed or divorced).

Comorbidity

Information on all somatic diagnoses other than endometrial cancer was obtained from the National Hospital Discharge Registry, which contains information on all admissions to hospitals in Denmark since 1978 and from 1994 also includes outpatient visits [Citation13]. All contact diagnoses were coded into the Charlson comorbidity index, which consists of 19 somatic conditions scored from 1 to 6 by degree of severity [Citation14]. The scores were summed until one year before the endometrial cancer diagnosis and grouped into 0 (none), 1, 2 and ≥3 for the analysis.

Lifestyle factors

The DGCD database contains information on lifestyle factors obtained from questionnaires filled in by patients before surgery. We used information on smoking status (current smoker, ex-smoker, never smoker), height and weight. BMI was classified according to the definitions of the World Health Organization [Citation15] into underweight (BMI <18.5), normal weight (18.5–25), overweight (25–30) and obese (BMI ≥30). Information on smoking status was missing for 18.5% of patients and on height or weight for <3%. Missing information was grouped as unknown.

The distribution of cancer characteristics, treatment, comorbidity and lifestyle factors by level of education is presented in .

Table 1. Descriptive characteristics of 3638 women with endometrial cancer diagnosed in 2005–2009 in Denmark

End-points

Death from all causes was the outcome of the Cox analysis. Patients were followed from the date of diagnosis until death, emigration or the end of 2011, whichever came first.

Stage of cancer was the outcome of the logistic regression analysis.

Method

Statistical analysis

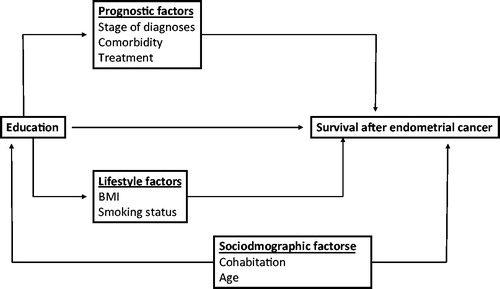

Before we analysed the data, we drew a simplified causal diagram of the associations between length of education and survival after endometrial cancer (), the direction of the arrows distinguishing between confounders and intermediates.

Figure 1. Hypothesized causal relations between education, sociodemographic factors, clinical prognostic factors, lifestyle factors and survival after endometrial cancer.

Logistic regression was used to analyse the association between level of education and cancer stage (). Model 1 was adjusted for age, and Model 2 was further adjusted for comorbidity. The association between level of education and death from all causes was analysed in multivariate analyses with Cox proportional hazards regression models, with calendar time as the underlying time scale (). The proportionality assumption was tested graphically, and possible interactions between BMI and smoking status, BMI and comorbidity, smoking status and comorbidity, education and age, education and comorbidity, cohabitation and age and cohabitation and comorbidity were also tested. Significance was evaluated by χ2 testing. No significant interactions were found. Model 1 was adjusted for age, Model 2 for age and cohabitation, Model 3 with the addition of BMI and smoking, Model 4 with the further addition of comorbidity and Model 5 with the further addition of stage. The analyses were carried out in SAS 9.2, and p < 0.05 was considered significant.

Table 2. Odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for advanced stage at diagnosis among 3638 Danish women with endometrial cancer diagnosed in 2005–2009.

Table 3. Hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for death from all causes among 3638 Danish patients with endometrial cancer diagnosed in 2005–2009.

Results

The median age at diagnosis of endometrial cancer in the 3638 patients was 65.5 years, and the median follow-up time was 3.5 years. About a third (34%) had short education, 45% had medium education, and 21% had higher education. The women with short education had the highest proportion of stage IV disease, more were over the age of 75 years, more had unknown BMI and a Charlson score of ≥3 (). shows that women with short education had an age-adjusted odds ratio (OR) of 1.19 (95% CI 0.96–1.48) for advanced-stage endometrial cancer at diagnosis when compared with women with higher education. The OR for advanced-stage endometrial cancer increased with age. The OR for women with short education was unchanged by adjustment for comorbidity (OR 1.20, 95% CI 0.97–1.49).

Women with short education had an increased age-adjusted hazard ratio (HR) for all-cause mortality (1.47, 95% CI 1.17–1.80) and women with medium education a non-significantly increased HR of 1.10, 95% CI 0.90–1.35 when compared with women with higher education (, Model 1). A trend was found between living alone and increased all-cause mortality (HR 1.15, 95% CI 0.99–1.34) (, Model 2).

Women for whom information on BMI was missing, who were smokers or of unknown smoking status, who had comorbidity or an advanced cancer stage at diagnosis had significantly higher HRs for death. Stepwise inclusion of the potential mediating factors BMI, smoking status and comorbidity did not influence the estimates, whereas adjustment for stage attenuated the HR for women with short education to 1.36 (95% CI 1.11–1.67) and that for women living alone to 1.02 (95% CI 0.88–1.18) (, Model 5).

Discussion

Main findings

In this study of all women with endometrial cancer diagnosed in Denmark in 2005–2009, a significant association was found between level of education and overall survival after endometrial cancer, short education being associated with a higher HR for death. There was also a tendency to a more advanced cancer stage at diagnosis among women with shorter education, although this was not statistically significant. Stage appeared to explain part of the difference in survival by education, however, a 36% increased risk of dying persisted among women with short education after adjustment for confounders and mediators, including stage.

Education and stage at diagnosis

A study in the USA (N = 3556) in which an area-based measure of income was used found that women in the highest family income quartile had a lower risk for advanced-stage endometrial cancer than those in the lowest family income quartile, after adjustment for age, tumour grade and histology (OR 0.83, 95% CI 0.69–0.99) [Citation7–9]. Recent Danish studies found associations between individually measured level of education and advanced stage at diagnosis of breast, lung, rectal and cervical cancers and non-Hodgkin lymphoma, but not for colon cancer [Citation16–20]. We also found a trend of an association between level of education and stage at diagnosis. As education has been linked to an individual’s level of resources, cognitive function and perception of health education messages [Citation21,Citation22], better educated women may be more aware of symptoms and react accordingly. Thus, the indication of an association between educational level and stage at diagnosis might be due to differences in knowledge about unexpected post-menopausal bleeding or in the ability to communicate symptoms to a general practitioner or other medical specialist [Citation19].

Education and survival after endometrial cancer

In the present study, the statically non-significantly increased risk for death after endometrial cancer among women living alone was eliminated after adjustment for stage, indicating that the effect of having a partner is mediated by stage at diagnosis. Underweight women persistently had twice the risk for death as that of women of normal weight. After adjustment for smoking status, comorbidity and stage, very low BMI was an indicator of low general health status and a prognostic factor for survival. The risk for reverse causation remains, however, even after adjustment for stage, as low BMI might be a sign of undiagnosed progression of disease. In line with other studies, we found that age was associated with advanced-stage disease and a prognostic factor [Citation4,Citation23–25] and that the risk for death increases with increasing comorbidity [Citation5,Citation26–28]. The possibility of surgery and tolerance of oncological treatment might be reduced in patients with severe comorbidity, however, adjustment for comorbidity did not change the association between educational level and overall survival. The influence of comorbidity might nevertheless be underestimated, as the Charlson comorbidity index was calculated on the basis of all admissions and outpatient contacts, with no distinction between moderate and severe cases of disease. Further, the treatment opportunities for some conditions have changed since the Charlson weights were constructed [Citation14]. The index has, however, frequently been used in cancer research, and our descriptive results show a clear stepwise relation between the scores and survival, indicating that the Charlson Comorbidity Index is a valid measure of the burden of disease in this patient group.

Strengths of the study

Our study is based on a well defined study population of women with endometrial cancer registered in a clinical database with a high degree of completeness and validity and which fulfils the national standards for clinical quality databases [Citation9]. The use of nationwide administrative registries reduces selection bias and information bias because all the data were collected prospectively independently of study hypotheses. Misclassification of socioeconomic position was reduced by access to individual data on education and cohabitation status in administrative registers.

Limitations of the study

The missing data on lifestyle factors, especially smoking status, is a limitation of this study. As patients who are severely ill with advanced-stage endometrial cancer might not be measured properly because of other, more exigent issues, misclassification of BMI is a possibility. The mortality rates of women with unknown smoking status were similar to those of smokers, indicating that a high percentage may have been smokers or that they were in a generally poor health.

Inclusion of stage at diagnosis and comorbidity did not fully eliminate the association between education and overall survival, indicating the presence of other mediating factors or unmeasured confounding. We used education as a proxy measure for socioeconomic position. Inclusion of more detailed information on socioeconomic indicators might have added to the definition of social groups, however, for the purpose we a priori chose to focus on education. Education is to some degree correlated with income which is, i.e. to some degree associated with job status. Both income and job status may change over the life time, we chose education as our main social indicator, which is less influenced by age in adult life. Most women in this study underwent surgery (>92%); however, they may have had different subsequent treatment, such as adjuvant therapy or palliative care. We could not evaluate this possibility in the present dataset because of missing data on oncological treatment in the clinical database.

Conclusion

Short education and older age were associated with lower overall survival after endometrial cancer in this nationwide population-based study, pointing to a group of women who do not have the same outcomes as women with higher educational level and younger women, in spite of free access to health care in Denmark. As the stage of cancer partly explained the differences in survival, it is important to reach all social groups to ensure early detection of cancer. As some unexplained differences in survival were seen by educational level after adjustment for important prognostic factors, we suggest that more attention be paid to women in all age groups and vulnerable patients who enter the health care system and also during treatment and rehabilitation.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

References

- Faggiano F, Partanen T, Kogevinas M, Boffetta P. Socioeconomic differences in cancer incidence and mortality. IARC Sci Publ 1997;138:65–176.

- Woods LM, Rachet B, Coleman MP. Origins of socio-economic inequalities in cancer survival: a review. Ann Oncol 2006;17(1):5–19.

- Dalton SO, Schuz J, Engholm G, Johansen C, Kjaer SK, Steding-Jessen M, et al. Social inequality in incidence of and survival from cancer in a population-based study in Denmark, 1994-2003: summary of findings. Eur J Cancer 2008;44(14):2074–85.

- Engholm G, Ferlay J, Christensen N, Bray F, Gjerstorff ML, Klint A, et al. NORDCAN–a Nordic tool for cancer information, planning, quality control and research. Acta Oncol 2010;49(5):725–36.

- Jensen KE, Hannibal CG, Nielsen A, Jensen A, Nohr B, Munk C, et al. Social inequality and incidence of and survival from cancer of the female genital organs in a population-based study in Denmark, 1994-2003. Eur J Cancer 2008;44(14):2003–17.

- Hussain SK, Lenner P, Sundquist J, Hemminki K. Influence of education level on cancer survival in Sweden. Ann Oncol 2008;19(1):156–62.

- Hicks ML, Kim W, Abrams J, Johnson CC, Blount AC, Parham GP. Racial differences in surgically staged patients with endometrial cancer. J Natl Med Assoc 1997;89(2):134–40.

- Madison T, Schottenfeld D, James SA, Schwartz AG, Gruber SB. Endometrial cancer: socioeconomic status and racial/ethnic differences in stage at diagnosis, treatment, and survival. Am J Public Health 2004;94(12):2104–11.

- The Danish Gynecological Cancer Group. Landsdækkende klinisk database for kræft I æggestokke, livmoder og livmoderhals. National Årsrapport 2013/2014 [in Danish].

- Pedersen CB. The Danish Civil Registration System. Scand J Public Health 2011;39(7 Suppl):22–5.

- Pedersen CB, Gøtzshe H, Møller JØ, Mortensen PB. The Danish Civil Registration System. Dan Med Bull 2006;53:441–9.

- Jensen VM, Rasmussen AW. Danish education registers. Scand J Public Health 2011;39(7 Suppl):91–4.

- Helweg-Larsen K. The Danish Register of Causes of Death. Scand J Public Health 2011;39(7 Suppl):26–9.

- Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis 1987;40(5):373–83.

- World Health Organization. Physical status: the use and interpretation of anthropometry. Report of a WHO expert committee (WHO Tech Rep Ser 854). Geneva; 1995.

- Dalton SO, During M, Ross L, Carlsen K, Mortensen PB, Lynch J, et al. The relation between socioeconomic and demographic factors and tumour stage in women diagnosed with breast cancer in Denmark, 1983-1999. Br J Cancer 2006;95(5):653–9.

- Dalton SO, Frederiksen BL, Jacobsen E, Steding-Jessen M, Osterlind K, Schuz J, et al. Socioeconomic position, stage of lung cancer and time between referral and diagnosis in Denmark, 2001-2008, Br J Cancer 2011;105(7):1042–8.

- Frederiksen BL, Osler M, Harling H, Jorgensen T. Social inequalities in stage at diagnosis of rectal but not in colonic cancer: a nationwide study. Br J Cancer 2008;98(3):668–73.

- Ibfelt E, Kjaer SK, Johansen C, Hogdall C, Steding-Jessen M, Frederiksen K, et al. Socioeconomic position and stage of cervical cancer in Danish women diagnosed 2005 to 2009, Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2012;21(5):835–42.

- Frederiksen BL, Dalton SO, Osler M, Steding-Jessen M, de Nully BP. Socioeconomic position, treatment, and survival of non-Hodgkin lymphoma in Denmark–a nationwide study, Br J Cancer 2012;106(5):988–95.

- Louwman WJ, Aarts MJ, Houterman S, van Lenthe FJ, Coebergh JW, Janssen-Heijnen ML. A 50% higher prevalence of life-shortening chronic conditions among cancer patients with low socioeconomic status. Br J Cancer 2010;103(11):1742–8.

- Galobardes B, Shaw M, Lawlor DA, Lynch JW, Davey SG. Indicators of socioeconomic position (part 1). J Epidemiol Community Health 2006;60(1):7–12.

- American Society of Clinical Oncology. Cancer in Older Adults. Alexandria, Virginia; 2012.

- Mahboubi E, Eyler N, Wynder EL. Epidemiology of cancer of the endometrium. Clin Obstet Gynecol 1982;25(1):5–17.

- Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, Ferlay J, Ward E, Forman D. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin 2011;61(2):69–90.

- Andersen ZJ, Lassen CF, Clemmensen IH. Social inequality and incidence of and survival from cancers of the mouth, pharynx and larynx in a population-based study in Denmark, 1994-2003. Eur J Cancer 2008;44(14):1950–61.

- Eriksen KT, Petersen A, Poulsen AH, Deltour I, Raaschou-Nielsen O. Social inequality and incidence of and survival from cancers of the kidney and urinary bladder in a population-based study in Denmark, 1994-2003. Eur J Cancer 2008;44(14):2030–42.

- Roswall N, Olsen A, Christensen J, Rugbjerg K, Mellemkjaer L. Social inequality and incidence of and survival from Hodgkin lymphoma, non-Hodgkin lymphoma and leukaemia in a population-based study in Denmark, 1994-2003. Eur J Cancer 2008;44(14):2058–73.