Abstract

Background The study was performed to determine the epidemiological, clinical, and histopathological characteristics and prognosis of primary mucosal melanoma of the head and neck (MMHN) in Denmark.

Material and methods This was a national retrospective multicenter study of patients diagnosed with MMHN between 1982 and 2012 in Denmark. Data were retrieved from national databases and patient records. Incidence trends were examined for the entire period. We prepared survival curves and performed univariate and multivariate analysis for the period 1992–2012 to identify possible prognostic factors. Results No significant trends in incidence were found in the study period. The three-year overall and disease-free survival rates for MMHN were 46.5% and 35.5%, respectively. Negative margins was an independent predictor of disease-free survival, and age below 65, absence of distant metastases, and low overall TNM stage were predictors of overall survival. Radiotherapy did not improve survival significantly. Recurrence rates were high, even for patients with negative margins. Conclusions MMHN remains a rare disease with a poor prognosis, particularly for patients aged over 65, those with distant metastasis, and those with advanced TNM stage. Importantly, the rate of recurrence is lowest in patients with negative margins.

Mucosal melanoma (MM) is a rare type of melanoma, and one of the most challenging cancers due to its highly aggressive nature. The well established risk factors for cutaneous melanoma, i.e. ultraviolet radiation, family history of melanoma, and multiple benign or atypical nevi, do not pertain to MM [Citation1]. Although melanocytes in the mucosal layers of the head and neck are thought to be histologically identical to melanocytes in the skin [Citation1], the pathogenesis of MM―including MMHN―is unknown. Several etiological agents have been proposed for MMHN, including the use of tobacco and occupational exposure to inhaled carcinogens, but the results are inconclusive [Citation2].

MMs account for 1% of all melanomas, and half of the tumors occur in the head and neck area. Other sites include the gastrointestinal tract, the genitourinary tract, and the meninges [Citation3]. Only a few population-based studies have examined the incidence of MMHN [Citation2–5] and no uniform trends in incidence have been found.

Different staging systems for MM have been proposed and used. This challenges comparative studies of treatment and prognosis [Citation6–8]. MMHN was reclassified in 2009 in the Seventh Edition of the International Union Against Cancer (UICC) Classification of Malignant Tumors [Citation9], in order to improve tumor staging and prognostics. Previous studies have suggested a number of prognostic factors including age, gender, anatomic location, tumor size, pigmentation, mutations, nodal status, and distant metastasis [Citation10–12].

There are few evidence-based, implemented clinical guidelines for treatment of MMHN. Surgery is the treatment of choice. Radical tumor resection verified by histological tumor-free margins is the only curative treatment, and ensures the best possible tumor control [Citation13]. However, mutilating surgical procedures for large tumors are not recommended, and even with surgical treatment recurrence rates can be more than 50% [Citation12]. Radical resection does not prevent recurrence or metastases, and there is no established standardized recommendation for safety margins.

Overall, MMHN has a poor prognosis, which is reflected in the five-year survival rate of 10–39% [Citation1,Citation5,Citation6,Citation14].

Radiotherapy―as primary treatment or combined with surgery―is still controversial, but it may have some controlling effect locally [Citation11]. To date, chemotherapy and immunotherapy have not proven to have any beneficial effect on local control or survival [Citation15].

The aim of this study was to determine the incidence, clinical characteristics, histopathology, optimal therapy, and prognosis of MMHN in Denmark using extensive population-based registries and patient records.

Material and methods

From the Danish Pathology Registry, we identified all incident cases of MMHN recorded in the period 1 January 1982 through 31 December 2012. This registry is a national database that contains information on all pathology specimens examined by all Danish public and private pathology departments. Patients were identified using the Systematized Nomenclature of Medicine (SNOMED). The MMHN cases were defined from morphology codes for all malignant melanoma and topography codes for all head and neck areas. Topography codes for ocular sites, cutaneous and subcutaneous tissue were not included in this search. In most cases, histopathological diagnoses as described in the patients’ original pathology reports were verified using immunohistochemical staining, including some of the melanoma markers (e.g. S-100, HMB-45, and/or Melan-A). All pathological data was extracted from the database and no specimens were reexamined for this study.

We identified a total of 226 patients with the above morphology and topography codes. To ensure identification of primary MMHN cases and exclude metastasis from cutaneous melanoma, we linked the cases to the nationwide Danish Cancer Registry, which has listed all the cancer cases in Denmark since 1943. Thirty-four patients with previous cutaneous melanoma or with primary topography code for skin were excluded, as was one patient with melanoma in the parotid gland, leaving 191 patients with MMHN for our incidence study.

From the medical records at several of the university hospitals in Denmark, we retrieved clinical data on MMHN patients who were diagnosed between 1992 and 2012. This included comprehensive data on 98 of 139 patients whereas the remaining 41 patients did not have sufficient clinical data available. During the period 1982–2012, the treatment of MMHN in Denmark was centralized to the university hospitals. No cancer treatment was (or is) performed in the private sector. In addition, we retrieved data from the DAHANCA, a national clinical database that records all head and neck cancers treated in Denmark. It was not possible to retrieve sufficient data from medical records between 1982 and 1991.

Clinical data included information about symptoms, anatomical location, histopathology, stage at diagnosis, treatment modality, local, regional, and/or distant recurrence, and death. Tumor staging was done retrospectively from the medical records and from computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and positron emission tomography (PET) imaging when available according to the seventh edition of the UICC Classification of Malignant Tumors. Before starting the study, we were granted permission to obtain and analyze data from the Danish Data Protection Agency.

Statistical analysis

The Mann-Whitney U-test was used to assess differences between groups of continuous variables. The relationship between two categorical variables was explored using χ2-test.

Annual incidence rates were age-adjusted according to the 2000 World Standard Population. To identify trends in MMHN incidence over time, annual percent change (APC) was estimated. The APC was calculated by fitting a least-squares regression line to the natural logarithm of the age-adjusted rates, using the calendar year as a regressor variable. The following equation was used: y = mx + b, where y = ln(age-adjusted rates) and x = calendar years. The APC was then equal to 100 × (em−1). APC was calculated separately for men and women, and for sinonasal and oral location. To estimate the significance level of incidence changes over time, we tested the hypothesis that APC was equal to zero.

We estimated three-year survival rates for overall and disease-free survival using the Kaplan-Meier model. Overall survival was defined as the time from the initial diagnosis to date of death. Disease-free survival was defined as the time from first day of treatment to the first occurrence of local, regional, or distant failure. Patients were followed until death or the last day of follow-up, whichever occurred first. Univariate comparison of survival was performed using the log-rank test. Predictor variables with p-values less than 0.05 in univariate analysis were entered into multivariate analysis using a Cox proportional hazards model with backward elimination. All results are given as two-sided values. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software version 20.0.

Results

Incidence

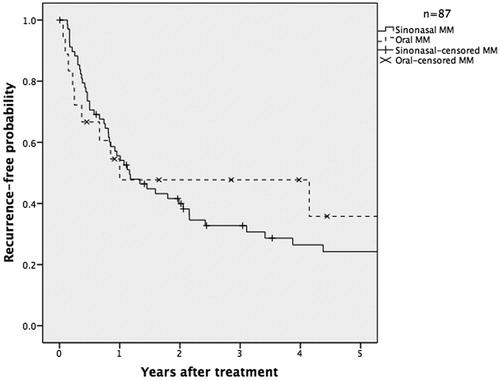

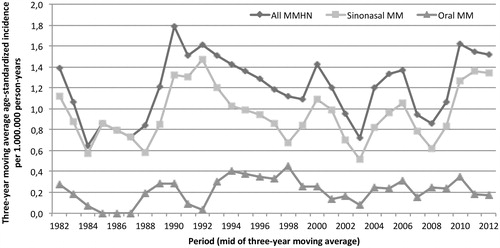

The 191 patients with primary MMHN comprised 106 women and 85 men, with an age range of 32–94 years and a median age of 72 years. The age-standardized incidence rate for MMHN overall was 1.2 per million person-years, and correspondingly, 0.9 and 0.2 per million person-years for the two dominant groups, i.e. sinonasal tumors (n = 157) and oral tumors (n = 10) (). A slight non-significant increase in incidence was found for MMHN over the entire study period (1982–2012) (APC, 0.9%; 95% CI −1.4–3.4).

Anatomical location and symptoms

Of the 98 patient records reviewed, we found 80 sinonasal melanomas and 18 oral cavity melanomas. Of the sinonasal tumors, 37 (46%) were located in the lateral nasal wall including the turbinates, nine (11%) in the nasal septum, seven (9%) in the maxillary sinuses, one (1%) in the ethmoid sinuses, one (1%) in the sphenoid sinuses, and 25 (31%) at an unspecified location within the nasal cavity. Of the oral tumors, seven (38%) involved the gingiva, five (28%) the hard palate, three (17%) the floor of the mouth, two (11%) the buccal mucosa, and one (6%) the lip mucosa.

The patients with sinonasal tumors mainly presented with epistaxis (n = 25), with nasal obstruction (n = 19), or with both symptoms (n = 25), and five patients had a combination of different symptoms.

Most patients with oral tumors presented with space occupying lesions, either alone or in combination with bleeding (n = 10), two patients presented with bleeding alone, and one patient had pain as the only symptom. Four patients (three with oral cavity MM and one with sinonasal MM) had no symptoms at diagnosis and the tumor was an incidental finding at the doctor or dentist. The symptoms were not described for seven patients. The time from first symptom to diagnosis ranged from 14 days to 49 month, with an average duration of six months.

Tumor staging

According to the current UICC TNM classification, 52 patients had T3 (53%), 28 had T4a (29%), 17 had T4b (17%), and data on one patient were unavailable. Regarding regional metastasis, 81 patients (83%) had no regional lymph node metastases at the time of diagnosis, seven had N1 (7%), and for 10 the status was unknown (Nx) (10%). Nodal metastasis at diagnosis was significantly more common for oral cavity tumors than for sinonasal tumors (22% vs. 4%; p = 0.01). For distant metastasis, 85 (87%) patients had no metastasis at presentation, eight (8%) had verified distant metastasis, and five (5%) could not be evaluated.

When we examined the clinical stage, we found that 50 cases were stage III (51%), 23 were stage IVa (24%), 12 (12%) were stage IVb, eight (8%) were stage IVc, and five were of unknown stage (5%).

Pathological findings

Problems in diagnosis were found for 24 patients (24%). Fourteen of these patients were misdiagnosed as low differentiated carcinoma, large cell carcinoma, esthesioneuroblastoma, or sarcoma and the remaining 10 patients underwent additional biopsy or histological reexamination due to uncertainty about the diagnosis. Most of these tumors had initially been biopsied and examined histopathologically at minor hospitals before referral to a university hospital, where the histopathology was reviewed. Twenty-eight patients had amelanotic tumors when examined microscopically. A small number of patients had macroscopically pigmented tumors, but did not show melanin pigment in the cytoplasm of the tumor cells or in the macrophages on histological examination. Ulceration of the tumor surface was found in 48 patients. Multifocality with tumor growth in islands was reported in 11 patients.

Treatment

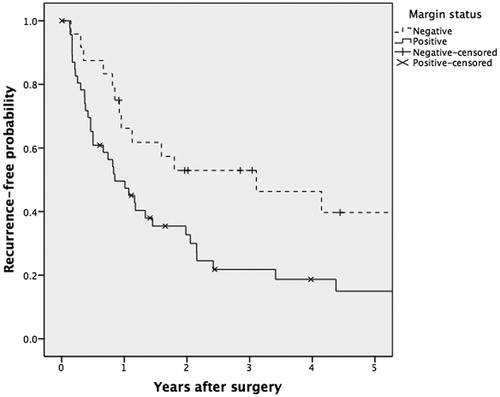

Sufficiently comprehensive treatment data were available for 93 patients (95%). Overall, 77 patients (79%) underwent surgery as part of the treatment. Twenty-four operations (31%) were microscopically with negative margins, based on a hematoxylin-eosin stained section. Negative margins were significantly more difficult to achieve for sinonasal tumors than for oral tumors (27% vs. 58%; p = 0.04). Forty-nine patients underwent surgery alone, 26 also received postoperative radiotherapy, and two received both radiotherapy and chemotherapy postoperatively. Eight patients received radiotherapy alone (with no surgery) and eight patients did not receive any treatment. Postoperative radiotherapy was used significantly more often in sinonasal MM patients than in oral MM patients (33% vs. 6%; p = 0.04). Postoperative radiotherapy did not significantly improve overall survival or disease-free survival.

Follow-up

The median follow-up time was 24.5 months. Two patients were lost to follow-up. There was recurrence in 62 patients (72%), with a median disease-free survival of 12 months (range, 54 days–16.4 years). Twelve patients were not included in the recurrence calculation due to either insufficient data or the palliative intention of treatment.

Thirty-four patients (40%) had local recurrence alone, three patients (3%) had nodal recurrence alone, five patients (6%) had distant metastases alone, and 20 patients (23%) had recurrence at more than one site.

In the patients with negative margins microscopically, 42% presented later with local recurrence. Distant metastases were found in the lungs (n = 7), bone (n = 6), and liver (n = 4), and six patients (7%) had more than one distant metastasis.

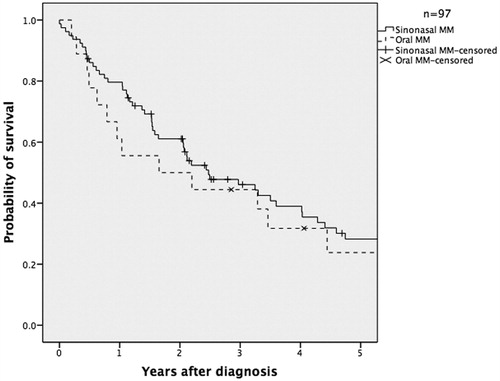

The three-year overall survival rate for MMHN was 46.5% and the disease-free survival rate was 35.5% ( and ).

Figure 1. Age-standardized incidence of mucosal melanoma of the head and neck in Denmark between 1982 and 2012.

A number of clinical and pathological variables were analyzed to assess their effect on recurrence and survival (). After univariate analysis, we found that patients with more advanced T-class, more advanced total stage, and pigmentation (as opposed to no pigmentation), and positive surgical margins (as opposed to negative margins) were more likely to experience local, regional, or distant recurrence. In multivariate analysis, only a positive surgical margin was an independent predictor of disease-free survival, with a hazard ratio of 3.3 (). Predictors of overall survival (according to univariate analysis) were age above below 65 years at diagnosis, absence of distant metastases, less advanced T-class, and less advanced overall TNM stage. In multivariate analysis, age, absence of distant metastases, and less advanced overall TNM stage remained predictors of overall survival.

Figure 4. Disease-free survival of MMHN patients with microscopically negative margins compared to positive margins in Denmark between 1992 and 2012 (p = 0.02).

Table 1. Factors influencing disease-free survival and overall survival in head and neck mucosal melanoma (n = 98).

Discussion

This study has given valuable epidemiological and clinical data for a homogenous population during a 31-year period, and is one of the most extensive studies on MMHN in an entire nation.

No significant trends in incidence were found for MMHN. The limited number of cases did not allow for a meaningful comparison of incidence trends between different gender or tumor sites. Our results are consistent with a Dutch epidemiological study from 2010 with 261 cases of MMHN obtained in the period 1989–2006, which found no significant changes in the incidence of MMHN over time [Citation16]. Two other recent studies, a Swedish study from 2013 [Citation5] and an American study from 2012 [Citation2], showed a significant increase in incidence for sinonasal MM during the study periods, which were 1960–2000 with 186 sinonasal MM cases and 1987–2009 with 452 MMHN cases, respectively. Both studies found a higher incidence of sinonasal MM in women. The increase in incidence may be explained by improved registration, improved histopathological diagnostics, and/or a true elevation due to exposure to inhaled carcinogens [Citation5]. Jangard et al. investigated a period that was earlier than our study period, which may account for the differences found in incidence trends.

Even though patients with sinonasal melanomas were older at presentation than patients with oral melanomas, we found no significant difference in disease-free or overall survival between the two groups. The age at presentation alone was as expected found to be a predictor of overall survival, with patients younger than 65 years having a significantly better overall survival than patients who were older than 65 years.

The proportion of amelanotic MMHN reported in the literature varies from 12.8% to 70.9% [Citation5,Citation17]. We found that 32% of the tumors were recorded as amelanotic, from microscopy. However, the difference between amelanotic melanoma and pigmented melanoma is not well defined in the clinical and pathological reports we had access to, or in previous studies [Citation5].

Amelanotic tumors are more problematic to detect, because they may resemble ordinary polyps. Most of the 14% of the patients who were initially misdiagnosed had (macroscopically) amelanotic tumors, and their biopsies were usually analyzed at smaller hospitals, where this diagnosis was rarely made. It is conceivable that misdiagnosis and a resultant delay in diagnosis and treatment could have influenced survival. We did not find that microscopic pigmentation influenced survival in our studies, but this may have been due to small numbers. Nevertheless, pigmentation has so far not been found to have any substantial influence on outcome [Citation12,Citation18].

The frequency of multifocality in MM has seldom been studied, but has been reported for 10–20% of cases [Citation12,Citation18]. Multifocality has not been found to be a prognostic predictor, which may have been due to small population sizes [Citation12]. In the present study, 11% of the tumors were multifocal and there tended to be poorer overall survival and disease-free survival for these patients.

The majority of patients (79%) underwent surgery, in most cases with curative intent. Negative margins were difficult to achieve for locally advanced tumors, due to vital structures in the respective area, with risk of dysfunction and esthetic disfigurement. Thirty-one percent had negative margins microscopically, which is slightly less than in previous studies [Citation14,Citation19]. Of these patients, 42% presented with local recurrence. Despite the high local recurrence rate, negative margins were an independent predictor of disease-free survival, which emphasizes the importance of radical surgery. However, it is likely that both multifocal melanoma lesions and in situ melanoma changes are more widely spread in the mucosa than previously acknowledged, and surgical resection margins evaluated in hematoxylin-eosin stained sections in most cases are not free. A recent study by Mochel et al. found that 83% of sinonasal MM had intraepithelial melanocytic proliferations, and these authors suggested that this represented precursor lesions [Citation20]. This might explain the high rate of local recurrence. To investigate this further, more rigorous histological investigation with systematic use of melanoma-specific immunohistochemical staining of the cancer fields and the resection margins is needed.

The role of postoperative radiotherapy and its impact on outcome in MMHN is controversial and has only been investigated in a few retrospective studies. We did not find that postoperative radiotherapy improved survival significantly in our study. However, two major studies have found that postoperative radiotherapy improved local control for patients with positive margins, but had no effect on survival [Citation21,Citation22]. Other studies have not found any effect on either local control or survival [Citation23]. An effect of postoperative radiotherapy is difficult to demonstrate in retrospective analyses, due to the inherent selection bias whereby patients with more advanced disease but less comorbidity are often treated more aggressively.

The guidelines on systemic therapy for MM lack consensus and most recommendations are based on retrospective studies. Though, this field is rapidly progressing [Citation24]. Recent studies of MMs have shown distinct molecular features compared to cutaneous melanoma. A considerable proportion of MMs have mutations and/or amplifications of the receptor tyrosine kinase KIT. In a study conducted by Carvajal et al. they screened 295 melanoma patients for the presence KIT mutations and amplification and found that 25% of MM patients had KIT mutations and/or amplifications [Citation25]. This has inspired further experiments on targeted therapy. Several clinical trials have shown improved progression-free and overall survival of melanomas harboring KIT mutations after treatment with imatinib, an inhibitor of multiple tyrosine kinases, including KIT [Citation25–27]. The majority of patients in one of these studies had MM [Citation27]. BRAF-inhibition of cutaneous melanoma in a phase III trial showed improved rates of overall and progression-free survival [Citation28]. However, only about 10% of patients with MM have BRAF V600 mutations and the question is whether these patients will see the same response as seen in patients with cutaneous melanoma [Citation24]. Immunotherapy has proven effective in the treatment of advanced cutaneous melanoma. Ipilimumab, an IgG antibody, has in a randomized phase III trial showed a survival advantage in melanoma patients with metastatic disease. In this particular study a few MM patients were represented [Citation29], but until now there have never been any randomized trials of ipilimumab in a population solely with MM patients [Citation24]. However, the development of targeted therapy and immunotherapy is of great clinical interest and may provide new treatment regimes for patients with MM and MMHN.

Our study has some limitations. The major weakness is that it is purely retrospective and descriptive and no pathology specimens were reexamined for this study. Furthermore, we were not able to retrieve clinical information from all identified MMHN patients in the period 1992–2012, which makes the study susceptible to selection bias. As clinical data was only obtained from university hospitals and not smaller hospitals, this population could represent the MMHN patients with more complex illnesses, more advanced tumor stages and less favorable prognoses.

In summary, we did not find any significant trends in incidence for MMHN in the Danish population during the period 1982–2012. We found that negative margins was an independent predictor of disease-free survival, and that age below 65 years, absence of distant metastases, and low total TNM stage were predictors of overall survival. The recurrence rate for MMHN was high, even for patients with negative margins. MMHN remains a rare disease with a poor prognosis. More national and multicenter investigations to identify clinical, pathological, and genetic prognostic factors and etiological factors are warranted to advance treatment of this aggressive melanotic disease.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

References

- Gavriel H, McArthur G, Sizeland A, Henderson M. Review: mucosal melanoma of the head and neck.. Melanoma Res 2011;21:257–66.

- Marcus DM, Marcus RP, Prabhu RS, Owonikoko TK, Lawson DH, Switchenko J, et al. Rising incidence of mucosal melanoma of the head and neck in the United States. J Skin Cancer 2012;2012:231693.

- Chang AE, Karnell LH, Menck HR. The National Cancer Data Base report on cutaneous and noncutaneous melanoma: a summary of 84,836 cases from the past decade. The American College of Surgeons Commission on Cancer and the American Cancer Society. Cancer 1998;83:1664–78.

- Chiu NT, Weinstock MA. Melanoma of oronasal mucosa. Population-based analysis of occurrence and mortality. Arch. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg 1996;122:985–8.

- Jangard M, Hansson J, Ragnarsson-Olding B. Primary sinonasal malignant melanoma: a nationwide study of the Swedish population, 1960-2000. Rhinology 2013;51:22–30.

- Thompson LDR, Wieneke JA, Miettinen M. Sinonasal tract and nasopharyngeal melanomas: a clinicopathologic study of 115 cases with a proposed staging system. Am J Surg Pathol 2003;27:594–611.

- Prasad ML, Patel SG, Huvos AG, Shah JP, Busam KJ. Primary mucosal melanoma of the head and neck: a proposal for microstaging localized, Stage I (lymph node-negative) tumors. Cancer 2004;100:1657–64.

- Ballantyne AJ. Malignant melanoma of the skin of the head and neck. An analysis of 405 cases. Am J Surg 1970;120:425–31.

- Sobin LH, Compton CC. TNM seventh edition: what”s new, what”s changed: communication from the International Union Against Cancer and the American Joint Committee on Cancer. Cancer 2010;116:5336–9.

- Jethanamest D, Vila PM, Sikora AG, Morris LGT. Predictors of survival in mucosal melanoma of the head and neck. Ann Surg Oncol 2011;18;2748–56.

- Krengli M, Masini L, Kaanders JHAM, Maingon P, Oei SB, Zouhair A, et al. Radiotherapy in the treatment of mucosal melanoma of the upper aerodigestive tract: analysis of 74 cases. A Rare Cancer Network study. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2006;65:751–9.

- Patel SG, Prasad ML, Escrig M, Singh B, Shaha AR, Kraus DH, et al. Primary mucosal malignant melanoma of the head and neck. Head Neck 2002;24:247–57.

- Pfister DGD, Ang K-KK, Brizel DMD, Burtness BB, Cmelak AJA, Colevas ADA, et al. Mucosal melanoma of the head and neck. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2012;10:320–38.

- McLean N, Tighiouart M, Muller S. Primary mucosal melanoma of the head and neck. Comparison of clinical presentation and histopathologic features of oral and sinonasal melanoma. Oral Oncol 2008;44:1039–46.

- Papaspyrou G, Garbe C, Schadendorf D, Werner JA, Hauschild A, Egberts F. Mucosal melanomas of the head and neck: new aspects of the clinical outcome, molecular pathology, and treatment with c-kit inhibitors.. Melanoma Res 2011;21:475–82.

- Koomen ER, de Vries E, van Kempen LC, van Akkooi ACJ, Guchelaar HJ, Louwman MWJ, et al. Epidemiology of extracutaneous melanoma in the Netherlands. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarker Prev 2010;19:1453–9.

- Bachar G, Loh KS, O'sullivan B, Goldstein D, Wood S, Brown D, et al. Mucosal melanomas of the head and neck: experience of the Princess Margaret Hospital. Head Neck 2008;30:1325–31.

- Mihajlovic M, Vlajkovic S, Jovanovic P, Stefanovic V. Primary mucosal melanomas: a comprehensive review. Int J Clin Exp Pathol 2012;5:739–53.

- Shuman AG, Light E, Olsen SH, Pynnonen MA, Taylor JMG, Johnson TM, et al. Mucosal melanoma of the head and neck: predictors of prognosis. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2011;137:331–7.

- Mochel MC, Duncan LM, Piris A, Kraft S. Primary Mucosal Melanoma of the Sinonasal Tract: A Clinicopathologic and Immunohistochemical Study of Thirty-Two Cases. Head Neck Pathol 2014;9:236--243

- Saigal K, Weed DT, Reis IM, Markoe AM, Wolfson AH, Nguyen-Sperry J. Mucosal melanomas of the head and neck: The role of postoperative radiation therapy. ISRN Oncol 2012;2012:1–7.

- Benlyazid A, Thariat J, Temam S, Malard O, Florescu C, Choussy O, et al. Postoperative radiotherapy in head and neck mucosal melanoma: a GETTEC study. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2010;136:1219–25.

- Lund VJ, Chisholm EJ, Howard DJ, Wei WI. Sinonasal malignant melanoma: an analysis of 115 cases assessing outcomes of surgery, postoperative radiotherapy and endoscopic resection. Rhinology 2012;50:203–10.

- Spencer KR, Mehnert JM. Mucosal melanoma: Epidemiology, biology and treatment. Cancer Treat Res 2016;167:295–320.

- Carvajal RD, Antonescu CR, Wolchok JD, Chapman PB, Roman R-A, Teitcher J, et al. KIT as a therapeutic target in metastatic melanoma. JAMA 2011;305:2327–34.

- Guo J, Si L, Kong Y, Flaherty KT, Xu X, Zhu Y, et al. Phase II, open-label, single-arm trial of imatinib mesylate in patients with metastatic melanoma harboring c-Kit mutation or amplification. J Clin Oncol 2011;29:2904–9.

- Hodi FS, Corless CL, Giobbie-Hurder A, Fletcher JA, Zhu M, Marino-Enriquez A, et al. Imatinib for melanomas harboring mutationally activated or amplified KIT arising on mucosal, acral, and chronically sun-damaged skin. J Clin Oncol 2013;31:3182–90.

- Chapman PB, Hauschild A, Robert C, Haanen JB, Ascierto P, Larkin J, et al. Improved survival with vemurafenib in melanoma with BRAF V600E mutation. N Engl J Med 2011;364:2507–16.

- Hodi FS, O'day SJ, McDermott DF, Weber RW, Sosman JA, Haanen JB, et al. Improved survival with ipilimumab in patients with metastatic melanoma. N Engl J Med 2010;363:711–23.