Abstract

Background The outcome of axillary ultrasound (AUS) with fine-needle aspiration biopsy (FNAB) in the diagnostic work-up of primary breast cancer has an impact on therapy decisions. We hypothesize that the accuracy of AUS is modified by nodal metastatic burden and clinico-pathological characteristics. Material and methods The performance of AUS and AUS-guided FNAB for predicting nodal metastases was assessed in a prospective breast cancer cohort subjected for surgery during 2009–2012. Predictors of accuracy were included in multivariate analysis. Results AUS had a sensitivity of 23% and a specificity of 95%, while AUS-guided FNAB obtained 73% and 100%, respectively. AUS-FNAB exclusively detected macro-metastases (median four metastases) and identified patients with more extensive nodal metastatic burden in comparison with sentinel node biopsy. The accuracy of AUS was affected by metastatic size (OR 1.11), obesity (OR 2.46), histological grade (OR 4.43), and HER2-status (OR 3.66); metastatic size and histological grade were significant in the multivariate analysis. Conclusions The clinical utility of AUS in low-risk breast cancer deserves further evaluation as the accuracy decreased with a low nodal metastatic burden. The diagnostic performance is modified by tumor and clinical characteristics. Patients with nodal disease detected by AUS-FNAB represent a group for whom neoadjuvant therapy should be considered.

Axillary nodal status remains an important prognostic factor in primary breast cancer [Citation1] despite the implementation of novel genomic analysis and advances in routine pathology. The method used for axillary staging has evolved from axillary lymph node dissection (ALND) to the sentinel node biopsy technique (SLNB) for clinically node-negative patients [Citation2,Citation3]. For patients with a benign SLNB or a minor tumor burden in the form of isolated tumor cells (ITCs) or micro-metastases [Citation4,Citation5], no further axillary surgery is recommended. The ACoSOG Z0011 randomized trial suggested that not performing ALND in patients with two or fewer macro-metastases did not negatively influence survival compared with that of patients in whom axillary clearance was performed [Citation6], and thus the value of ALND has been questioned in these patients. For patients with three or more positive SLNBs, ALND is still recommended; this is also a group of patients for whom neoadjuvant therapy is recommended [Citation6,Citation7].

The diagnostic work-up for primary breast cancer ideally includes routine axillary ultrasound (AUS), in which the nodes are evaluated according to established criteria for metastatic involvement, including nodal size and morphology [Citation8,Citation9]. For patients in whom the AUS indicates metastatic nodal involvement, complementary fine-needle aspiration biopsy (FNAB) or core needle biopsy (CB) is performed. A major concern, however, is that nodal metastases that are diagnosed by ultrasound may be indicative of a high tumor burden [Citation7,Citation10]. Recent studies have examined the accuracy of methods for the detection of limited disease in the axilla [Citation11]. Other studies have been conducted to investigate whether preoperative axillary ultrasonography with or without fine-needle aspiration can reduce the number of sentinel lymph node procedures [Citation9] and whether worrisome macro-metastases can be detected by preoperative AUS [Citation12]. The clinical utility of preoperative ultrasound and cytology has been questioned [Citation13–15], including whether the technique can distinguish between patients in whom ALND is recommended and those in whom it can be omitted. Of particular research interest is whether the accuracy of the method is modulated by factors including metastatic burden in the axilla, tumor size, histological grade, and obesity; results in this regard have been equivocal [Citation16–18].

The aim of the present study was to assess the accuracy of AUS alone and in combination with FNAB in relation to nodal metastatic burden, particularized by number and size in mm of metastatic nodes, and compare axillary metastatic load in patients diagnosed by AUS and FNAB with patients diagnosed by SLNB. An additional aim was to explore putative modifying factors, such as body mass index (BMI) and tumor biology, on the diagnostic outcome in a population-based prospective cohort.

Material and methods

Study population

Patients who underwent surgery and axillary nodal staging for primary invasive breast cancer between January 2009 and December 2012 at Skåne University Hospital, Lund, Sweden, were identified in a prospectively maintained pathology-based registry. The exclusion criteria were a history of previous ipsilateral axillary surgery, neoadjuvant chemotherapy regimens, and bilateral tumors. The study was approved by the regional ethical review board of Lund University (reference EPN 2012/340).

Algorithm design

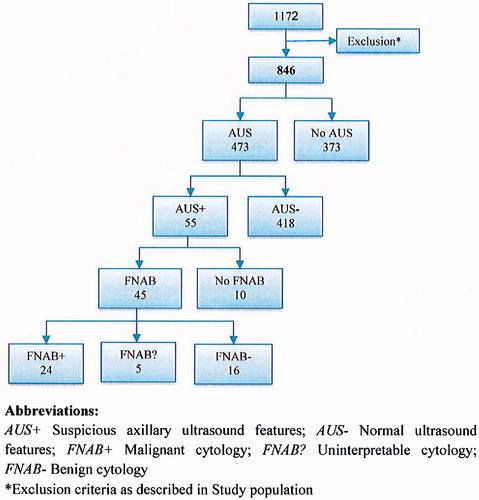

Routine preoperative axillary ultrasonography in patients with a suspicious breast malignancy was introduced in 2009 at Lund University Hospital and implemented over the following years. Surgeons of the Breast Surgery Unit performed the clinical breast and axillary examinations. Patients who presented with clinical lymphadenopathy underwent further preoperative staging of the axilla by either AUS-guided or freehand FNAB. Those with clinically negative axilla and suspicious AUS features then underwent AUS-guided FNAB, thus bypassing SLNB when nodal disease was confirmed by malignant cytology. When FNAB was contraindicated, proven inadequate cellular content despite repeat aspiration, or a benign cytological evaluation, SLNB became the diagnostic method of choice as displayed in . The presence of macro- as well as micro-metastases on SLNB indicated axillary node-positive patients; these patients were offered completion axillary node clearance according to the current Swedish National Guidelines [Citation5].

Clinical and histopathological data

Medical records were retrieved and retrospectively reviewed for mode of detection (dichotomized as screening or symptomatic presentation), age, clinical axillary status, and BMI. The Swedish national quality registry for breast cancer was reviewed for data on previous surgery on the breast and axilla. A breast pathologist (DG) extracted the following histopathological variables: tumor size, histopathological subtype, Nottingham histological grade, estrogen (ER) and progesterone receptor (PR) status, human epidermal growth factor 2 (HER2) status based on immunohistochemistry and in situ hybridization, Ki67 status, and evidence of vascular invasion. Axillary nodal characteristics based on FNAB, SLNB, and ALND included the total number of examined nodes, number of metastatic nodes, and size of the largest metastases (in mm and categorized into micro-/macro-metastases). ITCs were classified as node-negative.

Ultrasonography and FNAB

A radiology database at Skåne University Hospital Lund was reviewed for AUS results. Imaging was performed using the Toshiba Aplio XG US system (San Jose, CA, USA). A high-resolution multidimensional linear array transducer (7.2–14 MHz; PLT-1204AX) was used. Morphological sonographic features of the lymph nodes were determined to be normal or aberrant by a breast radiologist. The criteria for categorization of a lymph node as suspicious included cortical thickening, cortical eccentricity, absence of a fatty hilum, and hypoechoic nodes with an altered shape.

AUS-guided FNAB was accomplished by direct aspiration using a 10-ml plastic syringe attached to a conventional 21-gauge 50 mm needle (Braun Sterican®, Kruuse Svenska AB, Sweden) and aspiration device. The aspirated material was immediately mounted onto glass slides and alcohol-fixed. The smears were stained using a hematoxylin and eosin protocol. A specimen was considered adequate if there were a sufficient number of representative cells present in the target lymph node. The cytological diagnosis was categorized as C1-C5 according to the European guidelines for screening [Citation19].

Statistical analysis

The diagnostic performance of AUS and AUS-guided FNAB for the prediction of pathological nodal status was assessed with respect to sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, and negative predictive value. These primary outcomes were analyzed in subgroups of patients with a normal BMI and obesity. Mann-Whitney and χ2-tests were used to evaluate nodal involvement in patients with normal AUS features but a positive sentinel lymph node biopsy (AUS-SLNB+) compared with those with a positive ultrasound-guided biopsy (AUS + FNAB+). Significant and clinically relevant predictors were included in a multivariate analysis using logistic regression.

All statistical analyses were completed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 21.0 (IBM Corp. Armonk, NY, USA). All tests were two-tailed and p < 0.05 was used to indicate statistical significance.

Results

Study population

The search of medical and pathological records yielded 1172 cases of suspected breast malignancy. A total of 846 patients met the inclusion criteria by having an invasive breast malignancy without any pre-planned ALND; these individuals constituted the overall study population. AUS was performed in 473 patients, as shown in . Detailed patient and tumor characteristics in the overall study population and in patients who underwent AUS are listed in .

Table 1. Baseline patient and tumor characteristics.

Axillary ultrasound examination and fine-needle aspiration

AUS identified suspicious features in 55 patients; FNAB was performed in 45 of these individuals, while it was omitted in the remaining 10. All 24 patients with malignant AUS-guided cytology (C5) proceeded directly to ALND at the time of primary surgery. A flowchart of the preoperative axillary examination with outcomes of AUS and FNAB is included in . In 125 patients, a normal axillary sonographic exam was followed by a SLNB revealing metastatic lymph nodes. Axillary metastatic disease was found in 325/846 (38%) patients in the entire cohort, 234/325 (72%) of whom were found to have macro-metastatic deposits.

AUS alone had an overall sensitivity of 14/175(23%), specificity of 283/298 (95%), positive predictive value of 40/55 (73%), and negative predictive value of 283/418 (68%). The performance of AUS-guided FNAB was assessed for patients who underwent biopsy; in these cases, the sensitivity reached 24/33 (73%), the specificity was 12/12 (100%), the positive predictive value was 24/24 (100%), and the negative predictive value was 12/21 (57%). These results are outlined in .

Table 2. Performance characteristics of axillary ultrasound (AUS) and axillary ultrasound-guided biopsy (AUS-FNAB) in all patients and stratified by body mass index.

The performance characteristics of AUS and AUS-guided FNAB were stratified by BMI. The sensitivity and specificity of AUS alone were significantly better in obese patients 12/32 (38%) and 63/63 (100%) than in those displaying a BMI below 30 kg/m2 with 28/143 (20%) and 220/235 (94%), respectively. There were no BMI-related differences in the performances of AUS-FNAB. The relationship between the outcomes of AUS, AUS-FNAB, and BMI is displayed in .

Axillary pathological findings in patients diagnosed by AUS and SLNB

The pathological findings from ALND were compared between the subgroup of patients with negative AUS but positive SLNB findings (AUS-/SLNB+) and those with malignant AUS features preceding malignant FNAB findings (AUS+/FNAB+). The number of metastatic lymph nodes found by ALND was significantly higher in the AUS+/FNAB + group compared with the AUS-/SLNB + group (median of four positive nodes and one positive node, respectively). N2 or N3 disease was present in 13/24 (54%) of the AUS+/FNAB + group, all of whom exhibited macro-metastases without any evidence of micro-metastasis. In the AUS-/SLNB + group, 49/125 (39%) had micro-metastatic deposits and 18/125 (14%) of individuals were diagnosed with N2 or N3 disease. Accordingly, the median metastatic deposit size in the AUS+/FNAB + group was 15 mm, compared with 3 mm in the AUS-/FNAB + patients. The nodal characteristics of the subgroups are presented in .

Table 3. Nodal status in patients with normal axillary ultrasound features but a positive sentinel lymph node biopsy (AUS-SLNB+) in comparison with patients presenting positive ultrasound-guided biopsy (AUS + FNAB+).

Uni- and multivariate analysis for the prediction of performance of AUS

The capability of AUS to accurately detect metastatic lymph nodes was assessed by univariate logistic regression analysis, which indicated that the consideration of tumor size improved sensitivity, with a 3% (OR 1.03) improvement in outcome for each mm of increase in primary tumor size. Moreover, for each mm of increase in the size of nodal metastatic deposits, the performance improved by 11% (OR 1.11); it improved by 20% (OR 1.20) for each lymph node verified to have metastatic burden. In the univariate analysis, the performance of AUS was found to be significantly related to the Nottingham histological grade (NHG), with an odds ratio (OR) of 4.43 (grades III and II vs. grade I); HER2 status, with an OR of 3.66 (HER2-positive vs. HER2 normal); and Ki67, with an OR of 3.35 (Ki67 > 20% vs. ≤20%).

The inclusion of a variable in the multivariate analysis was based on clinical or statistical significance. In addition to ER status and patient age, any variable that was found to be significant based on the univariate analysis with p < 0.05 was selected as a candidate for the multivariate analysis. The stepwise inclusion of variables showed that the Ki67 status was related to the histological grade, as were the size of the largest nodal metastasis and the number of metastatic nodes. NHG and the size of metastatic deposits were included in the multivariate analysis model based on clinical significance, p-value, and overall statistical score in the univariate analysis. NHG and the size of metastatic deposits remained significantly positively correlated with AUS performance in the correct detection of nodal metastases, while HER2 status exhibited borderline significance. The results of the uni- and multivariate analyses are displayed in .

Table 4. Association of clinical and pathological predictors with abnormal axillary ultrasound (AUS).

Discussion

This study showed that the sensitivity of AUS for the detection of metastatic axillary lymph nodes (ALNs) in breast cancer was low. However, the performance improved when combined with ultrasound-guided biopsy, and the specificity increased from 95% to 100%. Axillary metastatic burden, indicated by the nodal metastatic size in millimeters and number of involved ALNs, was the most important predictor of abnormal AUS results indicating that the clinical utility of AUS is unreliable in patients with low nodal metastatic burden.

NHG was confirmed to add independent information on the accuracy of ultrasound performance and patients with HER2-positive tumors had higher rates of AUS abnormalities. Hackney et al. [Citation20] found that the most significant factor related to discordance between preoperative AUS and definitive histological evidence of lymph node metastasis was histological tumor type, and patients presenting with lobular breast cancers were at risk for under staging by AUS and biopsy. Tumor histological type and the performance of AUS was evaluated in this study displaying OR of 2.63 for ductal versus lobular cancer on abnormal AUS, but did not reveal any significant prediction. Our results indicated that for each metastatic lymph node, the prediction accuracy of lymph node status based on abnormal ultrasound results increased by 20%, while for each mm of metastatic deposit, the accuracy increased by 11% ().

We compared the axillary metastatic burden in patients diagnosed with nodal metastasis by ultrasound-guided biopsy (AUS + FNAB+) with that in patients with normal ultrasound findings but a metastatic sentinel node (AUS-SLNB+) and found that the total metastatic burden in the axilla was higher when diagnosed preoperatively. At the time of inclusion, all patients with micro- and/or macro-metastases in the SLNB underwent completion ALND, enabling a thorough comparison of the patients diagnosed by AUS + FNAB + or AUS-SLNB+. In all aspects, we found that the axillary metastatic burden was higher in the AUS + FNAB + group compared with the AUS-SLNB + group; a greater median number of metastatic lymph nodes, higher incidence of N2 disease, and a greater median metastatic deposit size (15 vs. 3 mm). These findings are in accordance with the meta-analysis findings by van Wely et al. [Citation7], suggesting that ultrasound-guided biopsy identifies patients with extensive nodal involvement.

The majority of studies on AUS and AUS-guided biopsy used FNAB and reported a wide range of sensitivities [Citation8,Citation21,Citation22]. We used FNAB and found a high rate of micro-metastases (39%) in the AUS-SLNB + group with positive nodal status, whereas in the AUS + FNAB + group, no micro-metastases were identified, supporting the notion that ultrasound-guided biopsy of the axilla is unable to detect minor tumor deposits in ALNs. Britten et al. [Citation8] examined the role of AUS and FNAB in a comparison of published performance statistics on AUS-guided biopsy and suggested that the identification of morphological changes by applying AUS-FNAB in lymph nodes with micro-metastatic burden was difficult. The authors reported a sensitivity of 26.7% for axillary core biopsy in detecting micro-metastases, whereas FNAB biopsies in the same cohort could not identify micro-metastatic deposits. In the retrospective study by Garcia-Ortega et al. [Citation23], axillary metastases diagnosed by ultrasound-guided core biopsy were all macro-metastases. The meta-analysis conducted by Houssami et al. [Citation22] revealed a pooled estimated sensitivity of AUS with or without biopsy of 55.2%, which is consistent with the findings from the systematic review by Diepstraten et al. [Citation21]. They described a pooled false-negative rate (FNR) of AUS with or without biopsy (FNAB/core biopsy) of 25%, and the pooled sensitivity was 50%. For purposes of comparison, our data revealed a FNR of 29% and sensitivity of 23% for AUS alone and sensitivity of 73% for AUS-FNAB.

The accuracy of AUS examination has been reported to be influenced by BMI; therefore we assessed the performance in obese (BMI ≥30 kg/m2) versus non-obese patients. The performance of ultrasound alone was significantly improved in obese patients, with a 2.5-fold increase in sensitivity and 100% specificity compared with those with a BMI <30 kg/m2. For AUS-guided biopsy, no difference in performance was observed with respect to BMI. The impact of obesity on the accuracy of preoperative AUS was assessed by Shah et al. [Citation18], who found similar sensitivity for detecting nodal metastases in obese and non-obese patients, while the specificity was superior in obese patients. Shah et al. suggest that while normal axillary nodes may be more challenging to identify in obese patients, abnormal hypo echoic nodes with thickened cortices are still readily able to be differentiated from the surrounding fat. The clinical implication is that AUS is a feasible diagnostic method in primary breast cancer also in obese patients.

Our study was limited by the fact that the proportion of node-positive patients included was relatively low due to the exclusion of patients with pre-planned ALND or those undergoing neoadjuvant therapies. Moreover, the final cohort was defined by the consecutive inclusion of patients in whom mammography screening was performed, and tumor characteristics were weighted toward a low-risk profile representative of breast cancer in the Swedish population. Thus, the proportion of patients with micro-metastatic deposits was relatively high and not detectable by AUS with or without FNAB. A particular strength of the study was that the cohort was prospectively collected, including radiological and detailed pathological register data. The SLNB technique was established at our institution a decade ago and includes a validated protocol for the evaluation of metastatic deposits with immunohistochemistry [Citation24]. The pathological data enabled us to perform a multivariate analysis of the accuracy of AUS using the clinical and tumor characteristics of NHG, ER, PR, HER2, and Ki67.

The use of preoperative AUS in patients with a suspicious breast malignancy was introduced in 2009 at Lund University Hospital. To explore whether the sensitivity of AUS improved after the establishment of the preoperative application of this method, we stratified the cohort by calendar year. The calculated accuracy was consistent during the first four years following the establishment of routine AUS (data not shown), indicating that the performance was not related to the introduction of the method. The criteria for classifying ALN as abnormal differ between studies. A diversity of morphological features, which may be seen in pathological nodes, e.g. cortical and hilum characteristics, has been defined [Citation8,Citation9], and the variable accuracy of such definitions makes each morphological attribute insufficiently trustworthy without FNAB, as supported by the higher accuracy of the combination of AUS with FNAB. A definitive scoring practise for standard implementation of the technique could be of significant value in the routine work-up of clinically node-negative patients.

Our study confirms that patients presenting with a morphologically abnormal AUS in combination with pathological FNAB have a significantly higher rate of nodal metastatic burden than those who are diagnosed by SLNB. For these patients, SLNB is unnecessary; however, further axillary treatment is recommended, and neoadjuvant therapy should be considered. The precision of AUS in combination with FNAB enables the preoperative diagnosis of extensive axillary disease and AUS is correlated with tumor characteristics and BMI. Supplementary prospective studies with large patient cohorts are ongoing [Citation15] and are necessary to clarify the role of this method in the preoperative diagnostic work-up of breast cancer patients in an era during which ALND is questioned.

Funding information

The study was supported by grants from Swedish Breast Cancer Organization (BRO), Skåne County Councils Research and Developmental Foundation and Governmental Funding of Clinical Research within the National Health Service (ALF).

Disclosure statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Fisher B, Bauer M, Wickerham DL, Redmond CK, Fisher ER, Cruz AB, et al. Relation of number of positive axillary nodes to the prognosis of patients with primary breast cancer. An NSABP update. Cancer 1983;52:1551–7.

- Veronesi U, Viale G, Paganelli G, Zurrida S, Luini A, Galimberti V, et al. Sentinel lymph node biopsy in breast cancer: ten-year results of a randomized controlled study. Ann Surg 2010;251:595–600.

- Giuliano AE, Haigh PI, Brennan MB, Hansen NM, Kelley MC, Ye W, et al. Prospective observational study of sentinel lymphadenectomy without further axillary dissection in patients with sentinel node-negative breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 2000;18:2553–9.

- Galimberti V, Cole BF, Zurrida S, Viale G, Luini A, Veronesi P, et al. Axillary dissection versus no axillary dissection in patients with sentinel-node micrometastases (IBCSG 23-01): A phase 3 randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol 2013;14:297–305.

- Swedish Breast Cancer Group. Nationellt vårdprogram 2014. Available from: http://www.swebcg.se/Files/Docs/NatVP_Brostcancer_2014-11-11_final[1].pdf.

- Giuliano AE, Hunt KK, Ballman KV, Beitsch PD, Whitworth PW, Blumencranz PW, et al. Axillary dissection vs no axillary dissection in women with invasive breast cancer and sentinel node metastasis: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2011;305:569–75.

- van Wely BJ, de Wilt JH, Francissen C, Teerenstra S, Strobbe LJ. Meta-analysis of ultrasound-guided biopsy of suspicious axillary lymph nodes in the selection of patients with extensive axillary tumour burden in breast cancer. Br J Surg 2015;102:159–68.

- Britton PD, Goud A, Godward S, Barter S, Freeman A, Gaskarth M, et al. Use of ultrasound-guided axillary node core biopsy in staging of early breast cancer. Eur Radiol 2009;19:561–9.

- Deurloo EE, Tanis PJ, Gilhuijs KG, Muller SH, Kroger R, Peterse JL, et al. Reduction in the number of sentinel lymph node procedures by preoperative ultrasonography of the axilla in breast cancer. Eur J Cancer 2003;39:1068–73.

- Castellano I, Deambrogio C, Muscara F, Chiusa L, Mariscotti G, Bussone R, et al. Efficiency of a preoperative axillary ultrasound and fine-needle aspiration cytology to detect patients with extensive axillary lymph node involvement. PLoS One 2014;9:e106640

- Moorman AM, Bourez RL, Heijmans HJ, Kouwenhoven EA. Axillary ultrasonography in breast cancer patients helps in identifying patients preoperatively with limited disease of the axilla. Ann Surg Oncol 2014;21:2904–10.

- Ibrahim-Zada I, Grant CS, Glazebrook KN, Boughey JC. Preoperative axillary ultrasound in breast cancer: Safely avoiding frozen section of sentinel lymph nodes in breast-conserving surgery. J Am Coll Surg 2013;217:7–15. discussion -6.

- Schipper RJ, van Roozendaal LM, de Vries B, Pijnappel RM, Beets-Tan RG, Lobbes MB, et al. Axillary ultrasound for preoperative nodal staging in breast cancer patients: Is it of added value? Breast 2013;22:1108–13.

- Houssami N, Turner RM. Staging the axilla in women with breast cancer: The utility of preoperative ultrasound-guided needle biopsy. Cancer Biol Med 2014;11:69–77.

- Gentilini O, Veronesi U. Abandoning sentinel lymph node biopsy in early breast cancer? A new trial in progress at the European institute of oncology of Milan (SOUND: Sentinel node vs Observation after axillary UltraSouND). Breast 2012;21:678–81.

- Stachs A, Gode K, Hartmann S, Stengel B, Nierling U, Dieterich M, et al. Accuracy of axillary ultrasound in preoperative nodal staging of breast cancer - size of metastases as limiting factor. Springerplus 2013;2:1–9.

- Cools-Lartigue J, Sinclair A, Trabulsi N, Meguerditchian A, Mesurolle B, Fuhrer R, et al. Preoperative axillary ultrasound and fine-needle aspiration biopsy in the diagnosis of axillary metastases in patients with breast cancer: Predictors of accuracy and future implications. Ann Surg Oncol 201320:819–27.

- Shah AR, Glazebrook KN, Boughey JC, Hoskin TL, Shah SS, Bergquist JR, et al. Does BMI affect the accuracy of preoperative axillary ultrasound in breast cancer patients? Ann Surg Oncol 2014;21:3278–83.

- European Reference Organisation for Quality Assured Breast Screening and Diagnostic Services. EUREF. Available from: www.euref.org/european-guidelines.

- Hackney L, Williams S, Bajwa S, Morley-Davies AJ, Kirby RM, Britton I. Influence of tumor histology on preoperative staging accuracy of breast metastases to the axilla. Breast J 2013;19:49–55.

- Diepstraten SC, Sever AR, Buckens CF, Veldhuis WB, van Dalen T, van den Bosch MA, et al. Value of preoperative ultrasound-guided axillary lymph node biopsy for preventing completion axillary lymph node dissection in breast cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Surg Oncol 2014;21:51–9.

- Houssami N, Ciatto S, Turner RM, Cody HS 3rd, Macaskill P. Preoperative ultrasound-guided needle biopsy of axillary nodes in invasive breast cancer: Meta-analysis of its accuracy and utility in staging the axilla. Ann Surg 2011;254:243–51.

- Garcia-Ortega MJ, Benito MA, Vahamonde EF, Torres PR, Velasco AB, Paredes MM. Pretreatment axillary ultrasonography and core biopsy in patients with suspected breast cancer: Diagnostic accuracy and impact on management. Eur J Radiol 2011;79:64–72.

- Grabau D, Ryden L, Ferno M, Ingvar C. Analysis of sentinel node biopsy - a single-institution experience supporting the use of serial sectioning and immunohistochemistry for detection of micrometastases by comparing four different histopathological laboratory protocols. Histopathology 2011;59:129–38.