Key words:

In 1913 Henrik Sjöbring presented his thesis, ‘Den individualpsykologiska frågeställningen inom psykiatrien’ [‘The question of individual psychology in psychiatry’] in Upsala Läkareförenings Förhandlingar (Citation1), the principal aim of which was to construct a system for characterizing the various dimensions of personality. The system presupposed that it is possible to distinguish different fundamental characteristics, or factors, in our innate psychic constitution and that combinations in different degrees of these fundamental characteristics could produce an infinite number of personality variations. Extreme positions, above and below the median, could result in mental illness. At that time this stance was new, but it corresponds well with contemporary beliefs.

A person’s personality and its importance for illness, particularly mental illness, has always been interesting, both generally and in medicine. For a long time, a barrier to meaningful typology was the inadequate knowledge about the ‘site of the soul’ and later, when the brain’s role in this connection was established, the functioning of the brain. At the start of the last century this issue was beginning to be dealt with in a more modern way, and Kraepelin’s classification in 1899 of two categories of ‘madness’, dementia praecox (schizophrenia) and manic-depressive psychosis, was crucial (Citation2-4). The importance of the personality in relation to mental illness is, however, probably most apparent in the case of less severe forms of illness, where a psychotic condition has not been able to eradicate to any great extent the personality’s fundamental characteristics. The development of psychology in the twentieth century has led to many different typologies, of which Henrik Sjöbring’s ‘individual psychology’ was the first with its systematic and modern approach that foresaw later developments. Sjöbring is generally acknowledged as Sweden’s most influential twentieth-century psychiatrist and a leading professor in psychiatry. Torsten Frey wrote in 1964:

If asked today to nominate a group of medical scientists, who more than others have made important contributions to man’s global reactions in health and illness, I would propose from Britain John Hughlings Jackson, from France Pierre Janet, from Germany Emil Kraepelin, from Austria Sigmund Freud, and from Russia Ivan Petrovitch Pavlov. For a Swedish name in this company I would not hesitate to propose Henrik Sjöbring (Citation5).

However, Sjöbring is not particularly well-known internationally, which is probably due to several factors. He usually wrote in Swedish and published his important, early articles in less widely spread fora (his thesis, in 1913, was published in Upsala Läkareförenings Förhandlingar (Citation1). In the same journal in 1920 he published ‘Förstämningar and förstämningspsykoser’ [‘Melancholy and melancholic psychoses’] (Citation6), in 1922 ‘Psykologi och biologi’ [‘Psychology and biology’] (Citation7), and in 1922 ‘Psychic energy and mental insufficiency’ (Citation8); in 1919 ‘Psykisk konstitution och psykos’ [‘Psychic constitution and psychosis’] was published in Svenska Läkarsällskapets Handlingar (Citation9). In addition, as has been pointed out in several of his biographies, his texts are somewhat difficult and written in a very abstract way, often without the facilitation of explanatory examples and concretization. It is also said that he was not prepared to compromise and had difficulty in accepting opinions that did not coincide with his own (Citation10-13). This could create problems not least during the time when Freud’s ideas from around 1910 had begun to attract many adherents. Sjöbring’s brief dismissal of the psychodynamic school is dealt with later in this article in connection with the review of his thesis. A citation from one of his opponents, Carl-Henry Alström in his book from 1945, Ytpsykologi Kontra Djuppsykologi [Superficial psychology versus profound psychology] (Citation14) reflects their differences on this issue:

The thoroughly dynamic perception of the development of the psychic phenomenon and the whole approach of his [Freud’s] comprehensive empirical investigations exposes a neurologist who, given the nature of his work, is forced to think in a distinctly dynamic and logical way. This is undoubtedly also the reason why Freud does not use a statistical approach which involves classifying people into predefined constitutional types, and which is always doomed to end in so called ‘buttonology’. Hence it is immaterial whether we choose to classify buttons according to qualitative factors, for instance shape (Kretschmer), or quantifiable factors such as size (Adler) or several quantitative factors, for instance not only size but also the number of holes (Sjöbring) (Citation14).

Biographic details about Henrik Sjöbring

Henrik Sjöbring was born in 1879 in Aringsås, Kronobergs County. His progenitor was the parliamentarian Per Jonsson from Hornaryd in the district of Växjö, who was married to Kerstin Jansdotter, who in her turn was the sister of the professor in Oriental languages in Uppsala from 1830, Pehr Sjöbring. Professor Pehr Sjöbring had adopted the name Sjöbring after his home parish Sjösås and the village Bringebäck in the district of Växjö, where his paternal grandfather was a famer. The parliamentarian Per Jonsson and his wife Kerstin had a son, Nils Persson, who also became a member of parliament and the speaker for the yeomanry. Nils Person and his wife from Sjösås, Lisa Jonsdotter, had two sons, Isac and Pehr, who both took the name Sjöbring. Isac became the lord of the manor, a farmer, and was the father of Henrik Sjöbring. The second son, Pehr, became the Bishop of Kalmar. Henrik attended school in Växjö, and written sources show that his mathematical aptitude was so great that the school master excused him from attending lessons. Henrik Sjöbring began studying medicine in Lund where he completed his preparatory medical studies in 1897. He took his bachelor of medicine in 1901 and qualified as a doctor with a medical degree from the Karolinska Institute in 1906 (Citation11,15,16). He had probably by then already established contacts with the Psychiatric Clinic in Uppsala, especially with Olof Kinberg, a well-known Swedish psychiatrist. Olof Kinberg was Assistant Physician at the hospital in Stockholm and the Uppsala Hospital between 1901 and 1906, after which time he started working at the mental hospital in Stockholm (Långbro). Kinberg wrote, in his obituary for Sjöbring: ‘Sjöbring began his psychiatric career in his early twenties as my locum at what was in those days called the Uppsala Hospital where he went on to serve for many years’ (Citation16). With short breaks, Sjöbring worked as a psychiatrist in Uppsala in various capacities from 1906 to the summer of 1929.

A brief history of the concept of personality up to 1913

Ever since the days of antiquity, there have been systems for classifying people into different ‘types’. From the time of Hippocrates we have the terms sanguine, melancholic, choleric, and phlegmatic, resulting from an excess of the bodily fluids: blood, black gall, yellow gall, and phlegm. The Hippocratic School of the fifth century BC discussed the philosophy of the character of the people, their national characteristics, and the importance of the physical and the psycho-social environment in the formation of a national character. The insight about a strong inherited component in character or temperament was noted already by Galen in the first century AD. Galen adhered to the Hippocratic ideas about the connection of bodily fluids with the four elements: heat, cold, damp, and dryness. However Galen was already aware that these different elements could be combined in different ways. Galen related the excess of black gall (mela chole) to melancholic depression and a predisposal to depressed moods. It was believed that black gall derived from unclean blood that was transported to the spleen, which caused a predisposition for what later became known as a splenetic mood or melancholia. The yellow gall (chole) was related to a tendency to be irritable and hot-tempered (choleric), blood (sanguis) to optimism (sanguineous), and phlegm to indifference or being phlegmatic. That this relationship between an excess of any of the four body fluids and the four temperaments later became so well-known, even to the general public, can be attributed to Philip Melanchton in the mid-sixteenth century, chiefly through the spread of country almanacs. Melanchton, the great friend of Martin Luther, was a professor in Greek at Wittenberg, but he also wrote books on psychology that were widely read and he was considered to have minted the concept ‘psychology’ (Citation17-20).

During the latter part of the eighteenth century Franz Joseph Gall worked in Vienna. Gall believed that he could trace character and personality by studying the shape of the skull, phrenology. His hypothesis, which Gall strenuously tried to verify through measurements, was based on the idea that various spiritual characteristics existed in special areas of the brain, which could be detectable from the bumps at different places on the skull. Gall proceeded in a scientifically correct way according to the knowledge of the nervous system that existed at that time, and he was considered by many to be the first to proclaim a direct connection between the body and soul (Citation18). Another typology, arguably more based on reality, and which to a significant degree is a precursor to Kretschmer’s influential Köperbau und Character (1921), is Carl Gustav Carus’s attempt to write his constitutional doctrine in his work Symbolik der menschlichen Gestalt (1853). Carus built his theory on the belief that there is a relationship between the body type and mental constitution. The body types were based on the relationship between height and weight. Heavy weight could either be attributed to an athletic physique with choleric and strong spiritual energy or obesity usually linked to a less strong will but often more developed intelligence, sensitivity, and humour. Leanness could be differentiated as either a spiritual variant (quick, agile, energetic) or a poor variant with asthenic, stingy, and less intelligent traits (Citation18). A prominent name in psychiatry, Emil Kraepelin (professor in Dorpat in 1886, in Heidelberg in 1890, and from 1903 in Munich) had at the end of the nineteenth century played with ideas which somewhat resembled those that Sjöbring would present at a later date. However, Olof Kinberg, who had himself auscultated with Kraepelin, wrote: ‘But Kraepelin did not account for the totality of the human individual but stopped short with the study of those psychic symptoms, which constitute, through analytical thinking, isolated aspects of the psychic experience (perception, imagination, feelings, will, etc.)’ (Citation16). As if by chance Kraepelin presented his most thoroughly constructed thoughts about mental illness as a consequence of personality disorders in the eighth edition of his textbook in psychiatry, which was published in the same year as Sjöbring’s thesis, namely 1913.

In the literature around Sjöbring, three people are usually named as having had a great influence on his theories (Citation5,21). Theodor Lipps was one of the most important German philosophers at the end of the nineteenth century. Sjöbring borrowed the belief from Lipps that personality is basically an effort to reach a goal (Citation20). The type of goal can be concrete or abstract, or it may vary. The point is that this effort forms a characteristic manifestation in the individual. Sjöbring calls this effort ‘activity’. It is thus possible to claim that Lipps in this way promoted the importance of the subconscious, which explains why Freud was a great admirer of Lipps. Another person of importance for Sjöbring was the French psychologist and psychiatrist Pierre Janet, professor in comparative and experimental psychology at the College de France and doctor at Salpêtrières Mental Hospital in Paris from 1903. Janet, who was a pupil of the famous Charcot, had described in texts from 1894, 1898, 1903, and 1909 a system that was not wholly unlike Sjöbring’s, namely the appearance of three types of personality, which often reappeared in patients with asthenic-compulsory, hysterical-primitive, and manic-depressive disorder (Citation20). For Sjöbring, these three personality types came to be characteristic for sub-valid, sub-solid, and sub-stable individuals or patients—terms which will be described in more detail later. The third person of importance in the development of Sjöbring’s theory was Wilhelm Stern, born in Berlin in 1871 and employed as a lecturer in Psychology at the University of Breslau at the time Sjöbring was working on his thesis. In 1911 Stern published his book Die differentielle Psychologie in ihren methodischen Grundlagen. Stern was later awarded a professorship at the University of Hamburg where he stayed until 1933, at which time he emigrated to the USA as a consequence of his Jewish heritage. In the USA, he became interested in intelligence and the measuring of intelligence, and it was he who introduced the term intelligence quotient (IQ). Stern developed Janet’s ideas about individual psychology on the grounds of different fundamental factors, which he considered had a strong genetic component: ‘inheritance has by far the greatest, external environmental factors have by contrast a surprisingly meagre effect’ (Citation20). Sjöbring’s main achievement is that he constructed his system, based on common-sense analysis, introspection, and clinical observation, of which factors should be of fundamental biological importance, in contrast to Stern’s work that was based mainly on theoretical assumptions. The relationship between Stern’s and Sjöbring’s systems is probably why Sjöbring so often refers to Stern in his thesis of 1913, and often claims the superiority of his own system (Citation1).

Sjöbring forms his theory in articles written in Uppsala 1913–1919

In his thesis from 1913, which was simultaneously published in Upsala Läkareförenings Förhandlingar, Sjöbring explicates his theory of individual psychology (Citation1). It consists of the pattern of a number of mainly inherited personality variables, where each variable is independent from the others with a Gaussian distribution from low (sub-) to high (super-), but together representing the individual’s personality. In contrast to Stern, however, Sjöbring claims that research on individual psychology must be based on ‘a general comprehension of the psychology of personality’, which presupposes, as Sjöbring strongly claims, the necessity of perceiving different aspects of personality as qualities which can be combined in various ways with each other. Sjöbring expresses himself somewhat brutally (Citation1): ‘On the contrary, in regard to the subject in question, and vastly different (from Stern), I assert this in a one, two or multidimensional variation, the importance of which Stern has failed to grasp.’ Equally modern is Sjöbring’s claim that the constitutional (inherited) personality, ‘the particular disposition’, can be expressed in different ways depending upon childhood environment and vital events in life: ‘It is ab origine just a tendency, just a predisposition, which can develop during an individual’s lifetime. under the impact of various environmental influences’.

Sjöbring was of course aware that his theory of individual psychology could be difficult to use in psychiatric praxis, but he insists that the theory of normal psychology should nonetheless be followed as far as possible, even clinically, and that the transition between healthy and sick be flexible, an idea which appears to have the support of Kraepelin in his Psychologische Arbeiten (Citation4). When Sjöbring mentions the ‘abnormal’ personality in psychiatry he, at first, summarily dismisses the ‘psycho-analytical’ school by writing that it wrongly tries to explain the illness through ‘abnormal activities’ taking place because the individual has been taken out of ‘the normal conditions of the personality … and in that connection the environment as a factor of influence becomes predominant’. Sjöbring suggests, on the other hand, that there are two main reasons for an ‘abnormal’ personality, a degenerative and an organic reason. The degenerative reason implies that the constitutional, i.e. the inherited, personality is ‘abnormal’. It can be latent and appear only later in life, for example as with dementia praecox (schizophrenia). Another possibility is that every single personality variable lies within the normal area, but that an unlucky combination causes the patient to become mentally ill. The organic ‘abnormalities’, on the other hand, can be caused by ‘physical trauma, nutritional disorders, or toxic effects’ (Citation1).

On concluding his thesis Sjöbring looks ahead to his coming work, trying to identify the most meaningful personality variables: ‘From what I have said, it is clear that most essential and necessary for the work to move forward are further pilot studies to try to ascertain the units of disposition. Differential psychology has, as yet, hardly managed to do this at any point, and that serves to show the difficulties that need to be overcome’ (Citation1).

The work of identifying the most meaningful variables is described in the subsequent works in Upsala Läkareförenings Förhandlingar and presented in a summarized form in the essay from 1919, ‘Psykisk konstitution och psykos’ [‘Psychic constitution and psychoses’] (Citation9). Much later, in 1974, this essay was translated into English and published in the book Themes and Variations in European Psychiatry (Citation22).

The four variables suggested by Sjöbring as the psychical, constitutional fundaments are ‘capacity’, ‘validity’, ‘stability’, and ‘solidity’, where low and high variables are referred to, respectively, as sub- and super-. ‘Capacity’ is described by Sjöbring as ‘the greater or smaller possibilities for a nerve process’. The closest psychic expression for this capacity is intelligence or aptitude. A sub-capable individual can therefore be described as slow, single-minded, and with a low ability to comprehend complicated issues, while a super-capable individual can differentiate, is open-minded, and with an ability to think quickly. ‘Validity’ is the degree of mental energy with which the individual is equipped, and it is apparent, for example, in his or her degree of alertness and ability to work. A super-valid individual is vigorous and full of initiative, but also calm and collected. A sub-valid person, at the opposite end of the scale, is pedantic, long-winded, irritable, and tires quickly. ‘Stability’ according to Sjöbring, is a variable which in his own words he describes as ‘potential’, or with his invention of a new word as ‘baning’, with which he meant the individual’s ability to form circuits in the brain for new tasks, either of a mental or a physical nature. A simpler description could be the ability, without tiring, to execute a routine activity of a mental or physical kind. A super-stable person is objective and skilful in such a situation and performs with minimal emotion. The fourth variable, ‘Solidity’, encompasses the ability to retain the mental process in the form of memory and knowledge. The sub-solid personality is mentally and physically labile and has an erratic temperament. The sub-solid individual can also be charming and appears to be interesting and pleasant. The opposite, the super-solid, is mentally stable, objective, reliable, and thoughtful. On meeting such a person the individual may appear to be dry, boring, and difficult to make real contact with.

Personality and psychiatry after 1919 and Sjöbring’s time in Lund

The person most often named as a competitor, or co-runner, of Sjöbring, is Ernst Kretschmer. Kretschmer was professor of neurology in Marburg and became known throughout the world for his book published in 1921, Körperbau und Character, which has been translated into several different languages. In this work Kretschmer linked the body type with the personality, a perception that had existed as far back as classical times. Individuals with a pyknic physique, being broad and heavy, show an over-representation of cyclothymic traits, something that is often seen with patients who have a tendency towards cyclical, i.e. manic-depressive disorders. Individuals with a leptosomic physique, tall and thin, more often show asthenic, schizoid personalities and an over-representation of patients with schizophrenia. Kretschmer’s classification was easy to understand, and, besides, he had a simple, lively, and easily comprehensible way of presenting it, which contributed to his becoming famous, even outside his profession. Kretschmer was indeed able to show some empirical proof for his classification, but it lacks relevance in modern psychiatry (Citation18,20,21,23). Sjöbring’s constitutional theory was much more difficult to comprehend than Kretschmer’s, but it was also considerably more profound and, as would be shown, more relevant with regard to biology and psychology.

Sjöbring was naturally interested in an academic position to be able to pursue his science, and he therefore applied for professorships in Lund in 1923, in Stockholm in 1929, and in Uppsala the same year. However, the evaluation experts on these three occasions found it hard to comprehend the importance of Sjöbring’s work. It is easy to understand Sjöbring’s frustration, which is clearly expressed in the 20-page appeal he wrote against the negative decision in 1923 (Citation24). The experts, all of whom had considerable clinical experience, expressed the opinion that Sjöbring’s work was too remote from clinical reality. Sjöbring, who had tried to erect a general system from both his theoretical and common sense principles responded: ‘Under such circumstances it seemed to me not so important to document my findings with clinical examples. I will, however, in no way deny that clinical illumination would not have been desirable and that by so doing I would have found it easier to make myself understood and avoided a lot of misunderstanding.’ Sjöbring’s weighty language also in general made it hard to make his thoughts understandable: ‘Another remark that has been directed against my work is that I often stereotypically repeat myself. The thing is that I have considered myself forced in various essays to refer, as briefly as possible, to my fundamental philosophy and to provide the necessary terminology.’ August Wimmer, professor of psychiatry in Copenhagen, was one of the experts. Sjöbring summarizes his negative criticism in his appeal, ‘… that tries to demonstrate how Wimmer’s judgement is incompatible with a full understanding of the problems I raise …’. Wimmer felt that Sjöbring stood for scholastic and constructive formalism and compared him with Kretschmer, whom he saw as more clinically grounded than Sjöbring. In retrospect it is reasonable to suspect that Wimmer found it hard to penetrate Sjöbring’s writings, which over and above the complicated wording was written in a foreign language (Swedish). Sjöbring wrote, with a taunt also directed at Kretschmer: ‘It is thus not research which is foreign to the clinical reality, but rather a question of a purposeful attempt to reach out from a construction to a natural and reality-based approach. … It is, however, so that we cannot assume that the variations of the constitutional fundament may be able to be interpreted decisively from the surface changes.’ Bror Gadelius, who was the second evaluation expert, was professor of psychiatry at the Karolinska Institute from 1908 to 1929 and was considered Sweden’s leading psychiatrist during that time. Gadelius was contemporary with several of Sjöbring’s forerunners, for example Kraepelin, Bleuler, and Janet. Gadelius was very clinically minded, but also well versed in the world of research. The Svenskt Biografiskt Lexikon writes of Gadelius: ‘With all respect for the researcher Freud, he rejected the psychoanalytical dogmas (Citation25). He could not comprehend Henrik Sjöbring’s attempt to penetrate the depths of the fundamental problems of psychiatry’. Sjöbring was undoubtedly disappointed that Gadelius had not managed to appreciate his work: ‘This report is virtually wholly an inaccurate representation of what I truly believe, and this is particularly so with the basic philosophy itself …’. As an example, Gadelius criticized Sjöbring’s ideas about the presence of an etiological agent causing an ‘organic illness’ with psychiatric symptoms. However, Sjöbring’s conjecture that infections in the brain would be significant for mental disorders was criticized not only by Gadelius but also by others. At that time reports of residual mental effects of different kinds of encephalitis were rare. However, in Sjöbring’s defence it could be stated that his belief in etiological agents proved to be foresighted, since research on the connection between cerebral viral infections and both schizophrenia and depressive disorders is of great current interest with a lot of results supporting such a connection. The third expert, Teodor Nerander, had for a brief period, 1896–1902, been an extraordinary professor of psychiatry and head physician at the hospital in Uppsala, and had most probably met Sjöbring during his first year at Ulleråker Hospital, but in 1902 Nerander moved to a post as head physician at Lund’s Hospital. Nerander was considerably more careful in his report than the other two experts, and Sjöbring agrees with him that one cannot be certain how strongly his constitutional philosophy is conditioned by genetic factors. Like Wimmer, even Nerander comments on the similarity with Kretschmer’s theory of body types, which Sjöbring naturally opposes.

During the spring of 1929 Sjöbring was, however, offered the post of temporary professor and temporary head physician in Lund in 1929, and in 1930 he was awarded both posts fully. In Lund he had a solid base from which he could teach and gather a group of students around him at a clinic, which was the first psychiatric university-based clinic in Sweden. In general it seems that Sjöbring succeeded considerably better in person and orally than in his writing. The young doctors and doctoral students around him came to be called the ‘Lund School’, and their use and further development of Sjöbring’s system, as well as the easily accessible and clinically based theses and reports, helped to make the system known and frequently used by Swedish doctors. Sjöbring’s four variables, C, V, St, and So (Capacity, Validity, Stability, and Solidity) with plus (+) and minus – signs, were often used as a quick characterization of patients. For example, the combination So–St+ indicated a typical violent person—egocentric, easily aroused, and unmoved by the damage he caused.

Several members of the Lund School became prominent psychiatrists. Erik Essen-Möller succeeded Sjöbring as professor in Lund, and Bo Gerle and Gunnar Lundquist became authors of books and influential scientific reports. Torsten Frey was appointed professor of psychiatry in Uppsala 1960–1974 and Bengt Lindberg professor of psychiatry in Gothenburg (1953–1970). In 1956, at the time of Sjöbring’s death, there was no comprehensive picture of his ideas or writings, but in 1958 two of his former students, Erik Essen-Möller and Carl-Erik Uddenberg, edited and published his works in the book Struktur och Utveckling. En Personlighetsteori [Structure and development. A theory of personality] (Citation26). The book was translated into French in 1963 and into English in 1973. In addition to writing many articles about Sjöbring, Essen-Möller compiled ‘A Sjöbring Bibliography’ in 1977 (Citation27). There is also a comprehensive Festschrift, with contributions by Sjöbring’s pupils, edited by Bo Gerle and published at the time of Sjöbring’s retirement in 1944 (Citation28). Naturally, the Sjöbring variables were used retrospectively to characterize historical and well-known people as examples. For instance Gerle besides presenting an instructive scheme, characterized Sacha Guitry (light-hearted French writer and actor) as V+So–St+, Mussolini and Göring as V+So–St–, Karl Isakson (the extremely shy and self-critical Swedish painter) as V–So+St+, Virginia Woolf as V–So+St+, King Gustav III as V–So–St+, and Hans Christian Andersen as V–So–St– (Citation29). A standardized questionnaire with 60 questions, designed to measure the three variables, Solidity, Stability, and Validity, later became widely acknowledged and useful for clinical studies. The fourth variable, Capacity, could be measured better using an intelligence test. The questionnaire was developed by Sven Marke and G. Eberhard Nyman and is known as the Marke–Nyman Temperament (MNT) scale (Citation30). During the second half of the twentieth century, the relevance of the Sjöbring variables was validated through significant congruity with other internationally used scales for estimating mental conditions. Thus, the MNT scale was translated into Italian by Perris (Citation31), into English by Coppen (Citation32), into French by Pichot and Perse (Citation33), and into English for use in the US by Barrett (Citation34). Besides a number of clinical studies (Citation27), the validity of the MNT scale has also been confirmed by results showing a correlation with biochemical variables, such as cerebrospinal fluid levels of the serotonin metabolite 5-HIAA (Citation35) and with plasma levels of neuropeptide Y and cortisol (Citation36). It was also possible to detect a weak, but nonetheless significant, conformity between Sjöbring’s variables and Kretschmer’s theory of body types.

However, over time other scales, more relevant for clinical use and research, have been developed, and the MNT scale has been replaced with other instruments during the twenty-first century (Citation17,37). By the end of the twentieth century Sjöbring’s constitutional typography was beginning to be criticized, for other reasons too. Sjöbring’s rejection of psycho-social causes of mental illness and his connection with hypothetical processes in the brain, which started to become irrelevant with the scientific advances in brain research, came to be seen as old-fashioned. The lesion doctrine, which Sjöbring promoted increasingly, gained little support from researchers in the mid-twentieth century. This was partly because he called it encephalitis, yet his opponents could only rarely detect that a mentally ill patient had suffered from encephalitis, and in general the idea that a lesional disorder could cause mental symptoms was rejected. Sjöbring had even specified that, for example, many schizophrenic symptoms could result from a lesion causing a disruption in the intra-cortical connections—a fully modern interpretation that would have been viewed a few decades ago as extremely speculative. As mentioned earlier, the importance of inflammatory brain conditions for many mental illnesses has been revived and is currently of great interest.

Henrik Sjöbring’s old friend, Olof Kinberg, tried to characterize Sjöbring’s personality in an article in Svenska Läkartidningen, using Sjöbring’s own method (Citation16). As could be expected, Kinberg found him to be super-capable (C+). Sjöbring’s interest for theoretical argument, the world of ideas, and together with a certain aversion to being associated with concrete objects and tasks was deemed to be super-stable (St+). Super-stability could also express itself in a perfectly run house and garden and a strong interest in the fine arts. Super-stability also meant that Sjöbring had no great need of company, but in small groups where he felt comfortable he could be charming, amusing, boyish, and ironic about himself, which made him very popular—even though people felt they could not get very close to him. Kinberg is uncertain about Sjöbring’s degree of validity. Sjöbring had undoubtedly shown great perseverance and stamina in following through his work programme, but his great summary was never completed, despite his having worked on it for 10 years or more. That may be because, according to his friend Kinberg, Sjöbring modified his ideas time and again and chose not to publish his work in an unfinished state. As far as the fourth constitutional variable, solidity, was concerned, Sjöbring considered that he himself had a minor form of sub-solidity, reflected in his great ability to understand other people by identification and empathy (Citation16).

It is hard to know what Sjöbring was like as a clinician. Bo Gerle wrote of Sjöbring in his obituary in Lunds Dagblad: ‘One thing that always sparked his indignation was when a mentally sick person was subjected to unnecessary suffering because of the lack of understanding from the people around, or even more so the narrow-mindedness of bureaucratic officialdom. In dealing with his patients, Sjöbring had an unusual ability to very quickly reach the root causes …’ (Citation11). As an anecdote, Bo Lindberg, in his book about Salomon Eberhard Henschen, described what happened when Salomon’s brother, Esaias, was sectioned in connection with possible financial catastrophe: ‘Esaias described in a letter to Salomon what had happened. When he lay on his hospital bed as a result of coughing up blood from his lungs in February 1921, Professor Bergmark had entered the ward with Associate Professor Sjöbring. Sjöbring, whom he had not met previously, sat on a chair and stared at him for half an hour without saying a word, and later wrote his report that classified him as mentally ill’ (Citation38).

Henrik Sjöbring, who is considered by many to be Sweden’s most influential psychiatrist of the twentieth century, must have been a very special person, but a persistent impression after having got to know several of the eminent scientists of the early twentieth century, many of whom published their seminal ideas and discoveries in Upsala Läkareförenings Förhandlingar, is that most of them as a rule had personalities far from the usual—and maybe it takes such people to make new and original developments.

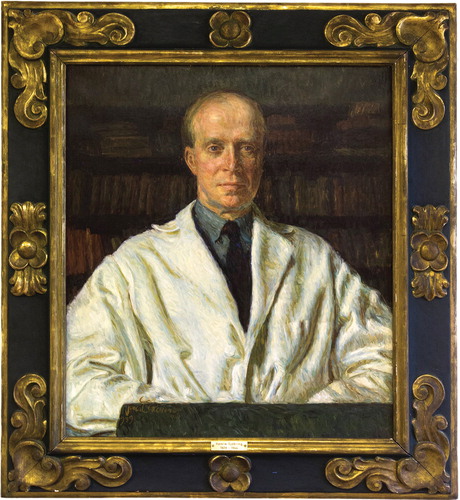

Figure 1. Henrik Sjöbring (oil painting). Psychiatric clinic, Lund. Photo: Roger Lundholm, Skånes universitetssjukhus.

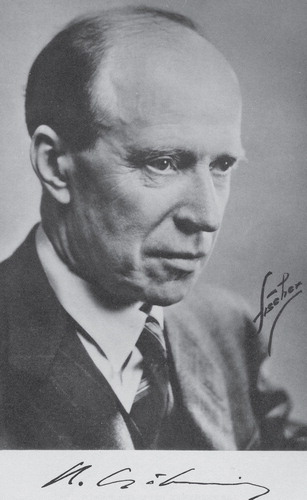

Figure 3. Henrik Sjöbring at the time of his retirement in 1944. Photo from ref. (Citation28).

Declaration of interest: The author reports no conflicts of interest. The author alone is responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

References

- Sjöbring H. Den individualpsykologiska frågeställningen inom psykiatrien. Upsala Läkareförenings Förhandlingar (NF). 1913–1914;19:1–60.

- Shepherd M. Kraepelin and modern psychiatry. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1995;245:189–95.

- Ljungberg L. Emil Kraepelin – en psykiatrins föregångsman. Forskning och Praktik (Sandoz). 1988;20:21–7.

- Kraepelin E. Psychologische Arbeiten. Leipzig: Wilhelm Engelmann; 1895.

- Essen-Möller E. The psychology and psychiatry of Henrik Sjöbring (1879-1956). Psychol Med. 1980;10:201–10.

- Sjöbring H. Förstämningar och förstämningspsykoser [Melancholy and melancholic psychoses]. Upsala Läkareförenings Förhandlingar (NF). 1920;25:73–112.

- Sjöbring H. Psykologi och biologi [Psychology and biology]. Upsala Läkareförenings Förhandlingar (NF). 1922;28:133–62.

- Sjöbring H. Psychic energy and mental insufficiency. Upsala Läkareförenings Förhandlingar (NF). 1922;28:163–214.

- Sjöbring H. Psykisk konstitution och psykos [Psychic constitution and psychosis]. Sv Läkarsällskapets Handlingar. 1919;45:462–93.

- Essen-Möller E. The teachings of Henrik Sjöbring. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1973;49:5–9.

- Gerle B. Henrik Sjöbring. Lunds Dagblad. 21 February 1956.

- Frey S, Son T. Henrik Sjöbring. Göteborgs Handels och Sjöfartstidning. 21 February 1965.

- Svenskt biografiskt lexikon. Luttenberger F: P. Henrik N. Sjöbring, urn:sbl:5983.

- Alström C-H. Ytpsykologi kontra djuppsykologi [Superficial psychology versus profound psychology]. Stockholm: Natur och Kultur; 1945.

- Svenskt biografiskt lexikon. Hägglund B: Pehr Sjöbring, urn:sbl:5984.

- Kinberg O. Henrik Sjöbring. Svenska Läkartidningen. 1956;20:281–1291.

- Millon T, Davis R, Chapter I. Conceptions of personality disorders: historical perspectives, the DSMs, and future directions. In Livesley WJ, editor. The DSM-IV personality disorders. New York: The Guilford Press; 1995.

- Landquist J. Temperament- och konstitutionsforskning från antiken till romatiken. Festskrift tillägnad Gunnar Castrén den 27 December 1938. Helsingfors: 1938.

- Harding G. Tidig svensk psykiatri. Lund: Verbum; 1975.

- Mattsson G. editor. Psykologisk Pedagogisk Uppslagsbok. Articles on Pierre Janet, Ernst Kretschmer, Theodor Lipps, William Stern Stockholm: Natur och Kultur; 1944.

- Nielzén S. Sjöbrings tankemodeller för personlighet och psykisk sjukdom. Sydsvenska Medicinhistoriska Sällskapets Årsskrift. 1980. p 124–33.

- Essen-Möller E. Henrik Sjöbring 1879-1956. In Hirsch SR, Shepherd M, editors. Themes and variations in European psychiatry. Bristol: 1974. p 261–3.

- Essen-Möller E. Sjöbrings variantlära. Svenska Läkartidningen. 1950;51:2925–36.

- Sjöbring H. Anmärkningar till sakkunniges utlåtanden rörande mina specimen till professuren i psykiatri vid Lunds universitet. Uppsala: Almqvist & Wiksells boktryckeri AB; 1923.

- Öberg L. Bror E Gadelius. Svenskt biografiskt lexikon. urn:sbl:14626.

- Sjöbring H. Struktur och utveckling, en personlighetsteori. In Essen-Möller E, Uddenberg CE, editors. Lund: Gleerups; 1973.

- Essen-Möller E. A Sjöbring bibliography. Nord Psychiat Tidskrift. 1977;81:323–38.

- Gerle B. editor. Henrik Sjöbring den 9 juli 1944 från vänner, kolleger, lärjungar. Lund: Gleerupska Universitetsbokhandeln; 1944.

- Gerle B. Sjöbrings psykiatri och det kliniska vardagsarbetet. Nord Med. 1957;57:3–11.

- Nyman GE, Marke S. Sjöbrings differentiella psykologi. Analys och skalkonstruktion. Lund: Gleerups; 1962.

- Perris C. Scala temperamentale di Marke e Nyman. Cremona: 1970.

- Coppen A. The Marke-Nyman temperament scale: an English translation. Br J Med Psychol. 1966;39:55–9.

- Pichot P, Perse J. Analyse factorielle et structure de la personalité. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1970:177–82.

- Barrett JEJr. Sjöbring personality dimensions: norms for some American populations. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1975;52:107–15.

- Banki CM, Arato M. Amine metabolites, neuroendocrine findings, and personality dimensions as correlates of suicidal behavior. Psychiatry Res. 1983;10:253–61.

- Westrin A, Engström G, Ekman R, Träskman-Bendz L. Correlation between plasma-neuropeptides and temperament dimensions differ between suicidal patients and healthy controls. J Affect Disord. 1998;49:45–54.

- Dåderman A, Lidberg L. Självbedömningsskalor avslöjar psykopati. Läkartidningen. 1998;95:383–90.

- Lindberg BS. Salomon Eberhard Henschen. En biografi [Salomon Eberhard Henschen. A biography]. Acta Universitatis Upsaliensis. Uppsala universitet; 2013. p 109.