Abstract

Background. A 57-year old man with low-back pain was found to have a 3 × 3 × 3 cm presacral neuroendocrine tumour (NET) with widespread metastases, mainly to the skeleton. His neoplastic disease responded well to peptide receptor radionuclide therapy (PRRT) with the radiotagged somatostatin agonist 177Lu-DOTATATE. During almost 10 years he was fit for a normal life. He succumbed to an intraspinal dissemination.

Procedures. A resection of the rectum, with a non-radical excision of the adjacent NET, was made. In addition to computerized tomography (CT), receptor positron emission tomography (PET) with 68Ga-labelled somatostatin analogues was used.

Observations. The NET showed the growth pattern and immunoprofile of a G2 carcinoid. A majority cell population displayed immunoreactivity to ghrelin, exceptionally with co-immunoreactivity to motilin. Somatostatin receptor scintigraphy and 68Ga-DOTATATE PET-CT demonstrated uptake in the metastatic lesions. High serum concentrations of total (desacyl-)ghrelin were found with fluctuations reflecting the severity of the symptoms. In contrast, the concentrations of active (acyl-)ghrelin were consistently low, as were those of chromogranin A (CgA).

Conclusions. Neoplastically transformed ghrelin cells can release large amounts of desacyl-ghrelin, evoking an array of non-specific clinical symptoms. Despite an early dissemination to the skeleton, a ghrelinoma can be compatible with longevity after adequate radiotherapy.

Introduction

It is unknown whether an overproduction of the growth-hormone-releasing 28-amino-acid-residue hormone ghrelin, with its multiple orexigenic physiological properties, can evoke clinical signs and symptoms in analogy with those of other well-known neuroendocrine syndromes, such as ‘insulinoma’, ‘glucagonoma’, ‘gastrinoma’, and ‘VIPoma’. Now, the term ‘ghrelinoma’ only refers to a clinico-pathological combination of: 1) a neuroendocrine tumour (NET), with a majority population of ghrelin-immunoreactive (IR) parenchymal cells; and 2) an elevated concentration of total ghrelin in the blood.

A third requirement should be claimed as well, namely that the hyperghrelinaemia has produced a distinct clinical syndrome. The task to fulfil that clinical requirement is one of the major aims of the present report. It is based on an account of the course of the neoplastic disease in a patient with a presacral malignant ghrelinoma.

Malignant ghrelinomas are rare. A pioneer report is from Uppsala University Hospital; the site of origin was the gastric mucosa (Citation1). Another one was a pancreatic NET (Citation2). There is also a third case in the rectum (Citation3). All had only brief survival times.

Presacral carcinoids are also rare. Until 2010, only 25 cases have been reported (Citation4). Most of them are associated with tailgut cysts or sacrococcygeal teratomas. These, and also those without such an association, are supposed to be of hindgut origin. Their immunohistochemical (IHC) profile is that of the common rectal carcinoid (Citation4).

The present case is unique. The patient’s hyperghrelinaemia could be followed for almost a decade. Such an opportunity to study its clinical effects has not been offered before. It should provide additional data about the presence of a clinical ghrelinoma syndrome.

Patient, methods, and observations

Patient course of the neoplastic disease

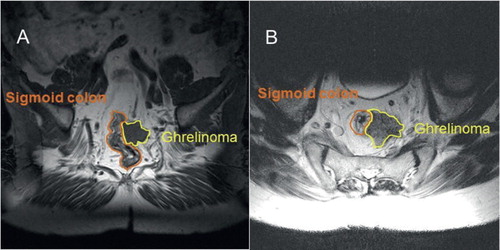

In 2002, a man, born 1945, body weight and height 90–96 kg and 171 cm, respectively, body mass index (BMI) 30.8–32.8, consulted the Ryhov Hospital, Jönköping, for recurrent bouts of low-back pain, radiating to the left groin and scrotum. A 3 cm round lesion was found, situated 7–8 cm above the anal sphincter. It was in contact with the left side of the gut wall, but the mucosa was intact. Dorsally, the lesion extended towards the vertebra S2, but was separated from it by an 8 mm rim of soft tissue. Medulla spinalis and cauda equina were normal. Needle biopsies taken from the tumour showed a highly differentiated (G2) NET. The diagnosis of a ‘presacral carcinoid’ was made (). Metastatic lesions were observed in the vertebrae Th5, Th9, and L3. The serum chromogranin A (CgA) concentration was normal. There was no 5-hydroxy-indol acetic acid (5-HIAA) in his urine. The patient never complained about classical carcinoid symptoms or about blood in the faeces. Hormonal assays of insulin, proinsulin, C-peptide, glucagon, gastrin, VIP, calcitonin, neuropeptide K, serotonin, and various catecholamines consistently gave results falling within their respective normal ranges. In addition to the low-back pain, his major symptoms were intermittent attacks of weakness, shivering, tachycardia, numbness, and profuse perspiration.

Figure 1. November 2003. A transverse T2-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) picture (A) and a coronal T1-weighted one (B), showing a fairly well-circumscribed tumour, measuring about 3 × 3 × 3 cm, located in the soft tissue ventrally to the sacrum, with overgrowth on the peripheral parts of the wall of the rectum. No tumour-like lesions occurred in the sacrum, neither in the coccyx, nor in the cauda equina.

In 2004, the tumour was extirpated by means of a resection of the recto-sigmoideum. Microscopically, the operation was found not to be radical. The tumour had then attained a size of 5 cm and was overgrowing and fixating the left ureter. Metastases occurred in 3 out of 13 lymph nodes. Thus, the NET was TNM staged as pT4 (5 cm), pN1 (3/10), cM1 (skeleton), R2b, G2, stage IV. A computerized tomography (CT) scan showed no signs of distant visceral metastases, neither in the liver, nor in the lungs. Soon a local recurrence (3 cm) appeared, and somatostatin receptor scintigraphy displayed high uptake values multifocally in the skeleton and in para-aortic lymph nodes.

In 2009 it was discovered that a majority of the neoplastic parenchymal cells of the presacral NET were immunoreactive (IR) to ghrelin and that they released that hormone to the blood, evoking hyperghrelinaemia (). The neoplastic disease was kept under clinical control by means of various kinds of treatment given to the patient (). This notwithstanding, the tumour progressed. The local recurrence became larger than 7 cm and the number of metastases increased, not only in the skeleton but also in the galea and the retro-orbital region, in between the cardiac auricles, and in the right kidney; the left kidney was silent. BMI was stable during the entire course of the neoplastic disease. There was never any diarrhoea. In September 2013 a biopsy of the spinal cord showed dissemination also to the central nervous system and the patient died. No autopsy was performed.

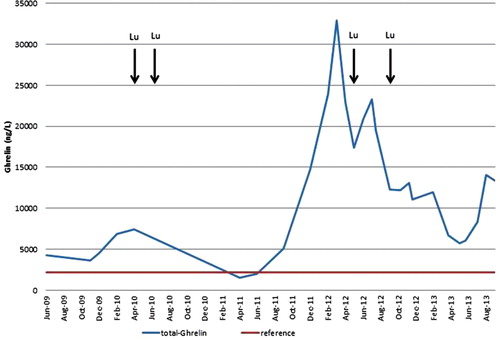

Figure 2. A graphic illustration of the variations in the patient’s blood serum concentrations of total (desacyl-)ghrelin during the time period from June 2009 through August 2013. Those of active (acyl-)ghrelin were consistently non-elevated. The variations were concomitant with those observed in the symptoms and with the clinical effects of the 177Lu treatments.

Table I. Survey of the various kinds of treatments received and their effects on the symptoms of the patient’s neoplastic disease.

Radiological methods and observations

The course of the disease and the therapeutic effects have been summarized in . In addition to MRI and CT, somatostatin receptor scintigraphy was used. Moreover, receptor positron emission tomography (PET) with 68Ga-labelled somatostatin analogues was applied (Citation5). An 18F radiotagged fluorodeoxyglucose (18FDG) PET was also carried out.

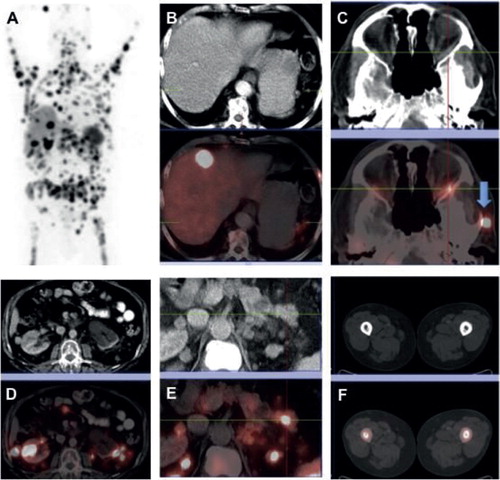

By means of a 68Ga-DOTATATE PET-CT (Citation5) a ‘superscan’ could be seen, detecting more than 100 metastatic lesions in the skeleton (). That indicated that the tumour cells were equipped with high amounts of somatostatin uptake vesicles (SUVs), thus expressing somatostatin receptors. As a consequence, it was found that the patient’s neoplastic disease responded well to peptide receptor radionuclide therapy (PRRT) with the radiotagged somatostatin agonists 177Lu DOTATATE or 177Lu DOTATOC (). There was no uptake of 18FDG-PET.

Figure 3. May 2012. A 68Ga-DOTATATE PET-CT revealed a ‘superscan’ during a progressive phase of the neoplastic disease. There were more than 100 metastatic foci in the skeleton, demonstrating high somatostatin uptake vesicles (SUVs), indicative of somatostatin receptor expression (A: maximum intensity projection image, MIP). Other metastatic sites included liver (B), retro-orbital space (C), kidney (D), pancreas (E), and the femur marrow bilaterally (F). (B–F images in the lower row represent fused PET-CT images corresponding to the CT ones shown in the upper row.)

Biochemical ghrelin assays

Measurements of both total and active ghrelin were performed with commercial RIA kits from Linco and Millipore (Billerica, Mass., USA). The serum concentrations of total ghrelin showed great variations during the course of the disease (). When the patient suffered badly, the total ghrelin values could amount to around 35,000 ng/L. After successful treatment, they fell to below 10,000 ng/L. A ‘non-symptomatic baseline’ of approximately 5,000 ng/L could be discerned, still about 2–2.5 times higher than the upper limit of the normal range. During the first part of the patient’s final time period from March through July 2013, when the neoplastic disease was still fairly stable, the serum concentrations of total ghrelin varied between 5,740 and 8,350 ng/L. When the disease ultimately progressed, they rapidly increased to 14,050 and 13,300 ng/L. In contrast, the serum concentrations of active ghrelin remained at a constant concentration of 34–38 ng/L.

Assays of CgA in blood and 5-HIAA in urine

Serum CgA assays were carried out regularly (Citation1,6,7). The serum CgA concentration continued to stay within its normal range throughout the whole course of his neoplastic disease. No 5-HIAA was ever detected in his urine.

Histopathological examinations and observations

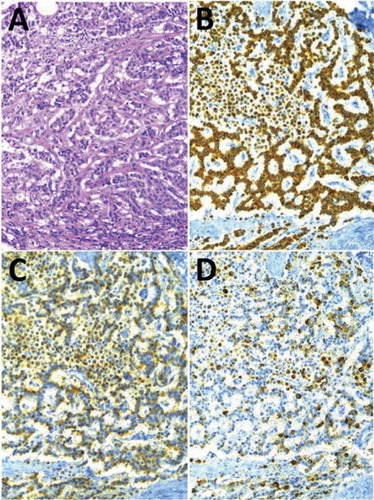

The microscopic growth pattern had a predominating trabecular structure, forming a delicate network of thin cords (). Areas of insular, glandular, or solid growth patterns occurred only sparsely. No ganglion cells or neurofibrillar structures were detected.

IHC examinations and observations

All tumour cells were of epithelial type, as evidenced by their immunoreactivity to the AE1/AE3 pancytokeratin antiserum (). In addition, practically all of them were IR to synaptophysin and CgA (), as well as against chromogranin B. A small fraction, roughly estimated to be one-tenth of the total number of tumour cells, was found to be non-IR to CgA (). Some of them turned out to be ghrelin-IR. The proliferation capacity, conventionally assessed with the 40× microscope objective on 10 visual fields, each with approximately 1,000 cells, by means of the commonly used MIB-1 antiserum (Citation1), was found to give an average Ki-67 index of about 5% with the presence of a few ‘hot spot’ areas up to around 10%.

As to the specific hormonal production, a majority of the tumour cells displayed a distinct immunoreactivity to ghrelin (). About two-thirds of the neoplastic cells were clearly ghrelin-IR. They were equally distributed over all parts of the tumour. Thus, they were not particularly numerous within the high Ki-67 index ‘hot spot’ areas.

An IHC analysis of the non-ghrelin-IR tumour cells was performed, using also indirect immunofluorescence, including double and triple immunostainings. No predominating cells expressing other peptide hormones or biogenic amines were found. All ghrelin-IR cells were also obestatin-IR (Citation8). A few PYY-IR cells were observed; they were devoid of ghrelin immunoreactivity. A coexistence was found between ghrelin and motilin in a few tumour cells. Two different motilin antisera gave the same result. Exceptionally, also ghrelin and somatostatin were found to coexist. None of the tumour cells displayed immunoreactivity against any of the following antisera: VMAT-2, serotonin, gastrin, GIP, CGRP, CART, calcitonin, ACTH, secretin, VIP, NRK, insulin, IAPP, glucagon, GLP-1, GRP, and neurotensin.

Classification

According to the current classification systems (Citation4) the patient’s NET was initially given the ICD-O morphology codes 8246/3 and 8013/3. No suitable ICD-O site code was found. The TNM classification made in 2004 became the ultimate one, namely T4, pN1, cM1, pL0, pV0, Pn0, R2b, and C4. The WHO grade of the NET neoplastic parenchymal cells was G2, Ki-67 5%, in hot spots up to 10%. The SUVs found corresponded to an IHC over-expression of the somatostatin receptor SSTR-2a. The neoplastic disease was in stage IV.

Ethical aspects

A couple of times during 2012 and 2013 the patient and his son were kind enough to read the manuscript in its then subfinal shapes, both in Jönköping and in Bad Berka, together with one of us (U.G.F.). They confirmed the presentation of the clinical history and consented to publication.

Discussion

Our patient’s hyperghrelinaemia evoked an array of just non-specific symptoms. This is a conclusion which conforms to those made in the preceding reports (Citation1-3). Thus, even a long-standing overproduction of desacyl-ghrelin does not produce any symptoms which can raise an immediate clinical suspicion that the NET diagnosed could be a ghrelinoma.

The third requirement for creating a clinical ‘ghrelinoma’ concept in general is not fulfilled. However, for a ‘ghrelinoma’, in particular for a presacral carcinoid, the third requirement is better fulfilled. Here, the peculiar combination of a non-serotonin-producing carcinoid with an early and widespread skeletal dissemination, longevity with absence of cachexia, normal CgA concentrations in the blood, and a hyperghrelinaemia, consisting of desacyl-ghrelin only, are signs and symptoms which may raise a clinical suspicion of the presence of a genuine ‘ghrelinoma’.

Whether or not non-neoplastic ghrelin-IR cells exist in sacrococcygeal malformations is unknown. It is not even quite clear whether they appear normally in the human rectal mucosa (Citation6,8). Thus, information about the cells of origin of the present ghrelinoma remains elusive.

As to the coexistence of ghrelin and motilin-IR in the tumour cells, it is of interest to know that similar observations have been reported in neuroendocrine cells in the normal human gut (Citation6). Thus, ghrelin and motilin are coexpressed in a prominent cell population of both the duodenal and jejunal mucosa. Likewise, the two hormones are cosecreted in pigs. In contrast, the ghrelin cells of the gastric mucosa are known to be devoid of motilin (Citation6). A gastric carcinoid has recently been found to display a coexistence of ghrelin and serotonin (Citation9).

The cause of the fundamental difference observed between the release to the blood of desacyl-ghrelin and those of CgA and acyl-ghrelin is obscure. Practically all the tumour cells were CgA-IR. An increase in the serum concentration of CgA is the classical marker for the presence of most kinds of NET (Citation10). A confusing fact is that normal ghrelin-IR cells in the human gastrointestinal mucosa are CgA non-IR (Citation6). Neoplastic human ghrelin-IR cells are, however, CgA-IR (Citation1,2). Previously reported ghrelinoma patients (Citation1-3) had elevated concentrations of CgA in the blood. They were, however, moderate and the observation times brief.

The mechanisms behind the low serum concentrations observed of active (acyl-)ghrelin can be that an antagonism exists between the two major ghrelin forms, namely acyl-ghrelin and desacyl-ghrelin, the latter being a non-octanoylated precursor in the production of the former (cf. 3). An excess of desacyl-ghrelin in the blood has experimentally been shown to suppress the serum concentration of acyl-ghrelin. Ghrelin’s orexigenic activity is exerted by the acyl-ghrelin, whereas the physiological activity of desacyl-ghrelin is unknown (cf. 3).

The interpretation of the observations made is that when the normal ghrelin-producing cells undergo a neoplastic transformation, they start to produce and release large amounts of desacyl-ghrelin. It is actually a tumour-pathological fact that when peptide-hormone-producing neuroendocrine cells become neoplastically transformed, they return to a preceding developmental stage in the synthesis and release of their hormonal products. A classic example is the insulin-producing beta cell of the islets of Langerhans. In poorly differentiated ‘insulinomas’ the major hormone produced and released is not insulin but proinsulin (Citation11).

The over-expression of SSTR found in the tumour cells explains the initially good clinical response on PRRT. There was, however, no SSTR down-regulation. Therefore, it is difficult to understand why the value of treatment with somatostatin analogues (SSA) during the very last few years of the patient’s disease became so questionable. Possible explanations may be that either the proliferative ability of the neoplastic cells had increased, or the tumour burden had become so extensive, that even high SSA doses were inefficient. In addition, it is known that SSA treatment with lanreotide is less effective in rectal NETs than in other enteropancreatic NETs (Citation12).

Our finding that the 18FDG PET showed no uptake confirmed the low proliferation rate of the NET cells and explained the observation that previously given chemotherapy did not result in any anti-tumour effect ().

Funding: The investigations were supported by grants from the Swedish Society of Medicine, the Foundation for Clinical Cancer Research in Jönköping, the Swedish Research Council, the Gyllenstiernska Krapperup, Fredrik and Ingrid Thuring, Magnus Bergwall, and Albert Påhlsson research funds, as well as from the Dinse Research Foundation, Hamburg, Germany.

Declaration of interest: The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

References

- Tsolakis AV, Portela-Gomes GM, Stridsberg M, Grimelius L, Sundin A, Eriksson BK, et al. Malignant gastric ghrelinoma with hyperghrelinemia. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:3739–44.

- Corbetta S, Peracchi M, Cappello V, Lania A, Lauri E, Vago P, et al. Circulating ghrelin levels in patients with pancreatic and gastrointestinal neuroendocrine tumors: identification of one pancreatic ghrelinoma. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88:3117–20.

- Walter T, Chardon L, Hervieu V, Cohen R, Chayvialle J-E, Scoazec J-Y, et al. Major hyperghrelinemia in advanced well-differentiated neuroendocrine carcinomas: report of three cases. Eur J Endocrinol. 2009;161:639–45.

- Bosman FT, Carneiro F, Hruban RH, Theise ND. editors. WHO classification of tumors of the digestive system. Lyon: IARC; 2010. p 133–77.

- Baum RP, Kulkarni HR. Theranostics: From molecular imaging, using Ga-68 labeled tracers and PET/CT, to personalized radionuclide therapy – the Bad Berka experience. Theranostics. 2012;2:437–47.

- Wierup N, Björkqvist M, Weström B, Pierzynowski S, Sundler F, Sjölund K. Ghrelin and motilin are cosecreted from a prominent endocrine cell population in the small intestine. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:3573–81.

- Landerholm K, Falkmer SE, Järhult J, Sundler F, Wierup N. Cocaine- and amphetamine-regulated transcript in nueroendocrine tumors. Neuroendocrinology. 2011;94:228–36.

- Grönberg M, Tsolakis AV, Magnusson L, Janson ET, Saras J. Distribution of obestatin and ghrelin in human tissues: immunoreactive cells in the gastrointestinal tract, pancreas, and mammary glands. J Histochem Cytochem. 2008;56:793–801.

- Latta E, Rotondo F, Leiter LA, Horvath E, Kovacs K. Ghrelin- and serotonin-producing gastric carcinoid. J Gastrointest Cancer. 2012;43:319–23.

- Syversen U, Ramstad H, Gamme K, Qvigstad G, Falkmer S, Waldum HL. Clinical significance of elevated serum chromogranin A levels. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2004;39:969–73.

- Creutzfeldt W, Arnold R, Creutzfeldt C, Deuticke U, Frerichs H, Track NS. Biochemical and morphological investigations of 30 human insulinomas. Correlation between the tumour content of insulin and proinsulin-like components and the histological and ultrastructural appearance. Diabetologia. 1973;9:217–31.

- Caplin ME, Paver M, Cwikla JB, Phan AT, Raderer M, Sedláčková E, et al. Lanreotide in metastatic enteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:224–33.