Abstract

Hypertensive emergency is an important entity which should be managed adequately. A 65-year-old woman presented with blindness and elevated blood pressure of 254/131 mmHg. She was diagnosed with hypertensive emergency on physical examination, and brain magnetic resonance imaging showed posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome (PRES) with bilateral thalamic haemorrhage. After controlling her blood pressure with intravenous antihypertensive agents, periaortitis and retroperitoneal fibrosis (RPF) were manifested by left hydronephrosis and creatinine elevation. She was diagnosed with periaortitis/RPF. Her blood pressure was well controllable, and PRES improved after treatment with prednisolone. Periaortitis/RPF should not be overlooked when hypertensive emergency suddenly occurs in patients with no history of hypertension.

Introduction

A hypertensive crisis is generally defined as a systolic blood pressure level ≥180 mmHg and/or a diastolic blood pressure level ≥120 mmHg.[Citation1] This entity is classified as hypertensive emergency and hypertensive urgency, with the level of urgency dependent on the presence or absence of vascular damage to the brain, heart, kidney and retina. In hypertensive emergency, immediate action must be taken to reduce the blood pressure as soon as possible to prevent target-organ damage.

We encountered a patient with a hypertensive emergency; severe hypertension and visual loss preceded the manifestation of periaortitis and retroperitoneal fibrosis (RPF), although she had been well with no history of hypertension. As far as we know, this is the first case in which hypertensive emergency, including blindness and posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome (PRES), preceded the progression of periaortitis/RPF.

Case report

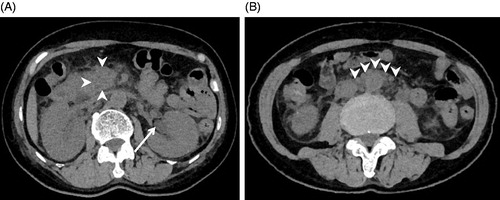

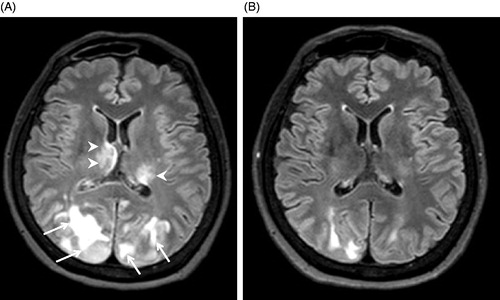

A 65-year-old woman without any past major medical history was referred to our hospital owing to severe hypertension and visual loss. She had initially consulted an ophthalmologist, and there was no papilloedema in the retina and no abnormalities in the anterior segment and transparent body. She was referred for an internal medicine consultation. Physical examination revealed light loss of reflex but no paralysis or motor abnormality. Since emergency head magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) using fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) pulse sequences revealed overt oedema in the occipital lobe and haemorrhage in the bilateral thalamus, she was subsequently hospitalized (). Her blood pressure was 254/131 mmHg and her body temperature was 37.3 °C. Laboratory tests performed at the time of admission revealed severe inflammation [white blood cells 32,940/mm3 and C-reactive protein (CRP) 23.6 mg/dl] without renal dysfunction (creatinine 0.91 mg/dl), diabetes or dyslipidaemia. The possibility of sepsis was ruled out by negative results in cultures and tests of blood, urine and sputum, endotoxin, beta-D-glucan and procalcitonin. In addition, autoantibody tests including antineutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibody were negative, and elevation of immunoglobulin G (IgG), IgM or IgA was not seen, including IgG4 (31.6 mg/dl). The possible coexistence of secondary hypertension was excluded by renal artery echography and computed tomography (CT), as well as laboratory tests including plasma renin activity and concentrations of plasma aldosterone, thyroid hormone, catecholamines and cortisol.

Figure 1. Brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) using fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR). (A) MRI on admission showing posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome (PRES, arrows) and bilateral thalamic haemorrhage (arrowheads); (B) MRI at day 17 showing improvement of PRES and thalamic haemorrhage.

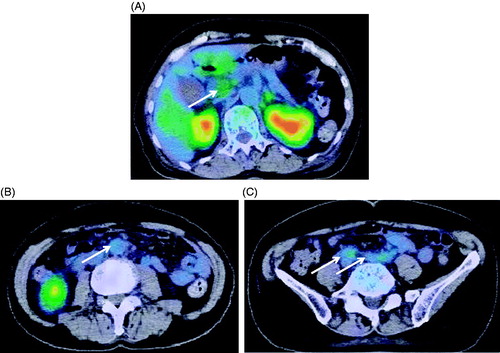

Antihypertensive therapy was started with intravenous nicardipine 4 mg/h to avoid target-organ damage. Since sepsis could not be ruled out at the time of admission, antibiotics were administered intravenously. After normalization of her blood pressure as a result of the treatment with antihypertensive agents, her visual disturbance gradually improved. At day 3, intravenous administration of nicardipine could be replaced with oral intake of cilnidipine 10 mg, losartan 50 mg and hydrochlorothiazide 12.5 mg daily. In conjunction with the normalization in blood pressure, the patient’s visual acuity fully recovered at day 7. A subsequent brain MRI revealed improvement of the oedema in the occipital lobe and the thalamic haemorrhage at day 17 (). Although gradual improvement was noted in her general condition, she continued to have a high fever along with a gradual elevation in creatinine level from 0.9 to 1.5 mg/dl. Abdominal CT showed left hydronephrosis and an increase in the fat tissue concentrations around the aorta and retroperitoneum, together with pancreatic head enlargement (), where pathological uptake was revealed by fluorine-18-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) at day 30 (). Based on these findings, she was diagnosed as having periaortitis and RPF. After treatment with prednisolone 1 mg/kg, her body temperature normalized and her general condition, including elevation of the white blood cell count and CRP, together with the left hydronephrosis, improved. Her blood pressure has become well controllable with the treatment of cilnidipine 10 mg twice daily after the cessation of losartan 50 mg and hydrochlorothiazide 12.5 mg daily.

Discussion

Here, we report a rare case of periaortitis/RPF in which hypertensive emergency was the initial symptom observed. Although we cannot exclude the possibility that unfavourable overall status promoted the exacerbation of the patient’s undiagnosed hypertension, we suggest that periaortitis/RPF itself may have caused the onset of hypertension. It has been reported that hypertension is present among 18–57% of patients with RPF.[Citation2] Importantly, new-onset hypertension has been commonly observed as one of the presenting signs and symptoms of RFP.[Citation3,Citation4] Although the precise mechanism of how periaortitis/RPF contributes to the development of hypertension is not known, acute hypertension may be related to a rise in renin release and/or volume retention by urinary tract obstruction. In addition, entrapment of the renal artery related to fibrotic change [Citation5–7] and renal artery thrombosis [Citation8] have also been proposed. However, in the present case, we did not observe stenosis or thrombosis in the renal artery by echography or CT. Plasma renin activity and aldosterone concentration at the time of the patient’s admission were within normal ranges. This may suggest an association with an unknown mechanism between periaortitis/RPF and marked systemic hypertension. Indeed, a 50-year-old woman complicated by RPF without renal artery stenosis on the CT scan or isotope renogram was reported to show severe hypertension with a generalized convulsion.[Citation9]

It has been reported that hydronephrosis itself may contribute to the development of severe hypertension.[Citation10] In this case, left hydronephrosis occurred as a result of RPF. When clinicians see a patient with hydronephrosis and uncontrollable high blood pressure, they should consider a number of neurohormonal abnormalities that are secondary to urinary tract obstruction, including activation of the renin–angiotensin system, reflex stimulation of the sympathetic nervous system, increased synthesis of renal prostaglandins and decrease in renomedullary vasodilator lipids.[Citation10] We cannot rule out the possibility that these factors contributed to the new onset of hypertension.

Although the present case did not fulfil the recently published diagnostic criteria of IgG4-related disease,[Citation11] we speculated that IgG4-related disease could be associated with periaortitis/RPF in the present patient because some patients with IgG4-related disease have a normal serum level of IgG4 despite the presence of positive IgG4 immunostaining in tissues.[Citation12] It has been reported that about half of the patients with IgG4-related disease present with features of periaortitis/RFP with raised CRP levels, and about one-third of patients present with autoimmune pancreatitis.[Citation13] The present patient showed increased fat density in the areas of her periaorta, retroperitoneum and pancreas head, with abnormal uptake of FDG in PET-CT, suggesting overt inflammation. Although the presenting features of periaortitis/RPF generally include hypertension, it remains unknown whether IgG4-related disease may contribute to the development and/or exacerbation of hypertension.

In conclusion, this is the first case in which a hypertensive emergency including blindness and PRES preceded the progression of periaortitis/RPF similar to that of IgG4-related disease. The possibility of periaortitis/RPF should not be overlooked in cases of hypertensive emergency, especially in patients with no history of hypertension and CRP elevation.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of this article.

References

- Lenfant C, Chobanian AV, Jones DW, et al. Seventh report of the joint national committee on the prevention, detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure (JNC 7): resetting the hypertension sails. Hypertension. 2003;41:1178–1179.

- van Bommel EF, Jansen I, Hendriksz TR, et al. Idiopathic retroperitoneal fibrosis: prospective evaluation of incidence and clinicoradiologic presentation. Medicine. 2009;88:193–201.

- Scheel PJ Jr, Feeley N. Retroperitoneal fibrosis: the clinical, laboratory, and radiographic presentation. Medicine. 2009;88:202–207.

- Smith LH III, Broadhurst RS. Retroperitoneal fibrosis as a cause of hypertension in an aviator: a case report. Aviat Space Environ Med. 1993;64:234–235.

- van Bommel EF. Retroperitoneal fibrosis. Neth J Med. 2002;60:231–242.

- Miles RM, Brock J, Martin C. Idiopathic retroperitoneal fibrosis. A sometime surgical problem. Am Surg. 1984;50:76–84.

- Birnberg FA, Vinstein AL, Gorlick G, et al. Retroperitoneal fibrosis in children. Radiology. 1982;145:59–61.

- Francklyn MM, Elombila M, Reddy AG, et al. Retroperitoneal fibrosis. Exceptional cause of renal artery thrombosis with secondary hypertension. J Cardiol Cases. 2014;9:26–28.

- Das D, Brigg J, Brown CM. Hypertensive encephalopathy in a patient with retroperitoneal fibrosis. Postgrad Med J. 1999;75:730–731.

- Oparil S. Hypertension in a 74-year-old man with hydronephrosis and coronary disease. Hypertension. 1985;7:824–833.

- Umehara H, Okazaki K, Masaki Y, et al. Comprehensive diagnostic criteria for IgG4-related disease (IgG4-RD), 2011. Mod Rheumatol. 2012;22:21–30.

- Deheragoda MG, Church NI, Rodriguez-Justo M, et al. The use of immunoglobulin G4 immunostaining in diagnosing pancreatic and extrapancreatic involvement in autoimmune pancreatitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5:1229–1234.

- Soliotis F, Mavragani CP, Plastiras SC, et al. IgG4-related disease: a rheumatologist’s perspective. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2014;32:724–727.