Abstract

Introduction. Socio-economic position (SEP) is a powerful source of health inequality. Less is known of early life conditions that may determine the course of adult SEP. We tested if early life stress (ELS) due to a separation from the parents during World War II predicts adult SEP, trajectories of incomes across the entire working career, and inter-generational social mobility.

Materials and methods. Participants (n = 10,702) were from the Helsinki Birth Cohort Study 1934–44. Compared to the non-separated, the separated individuals attained a lower SEP in adulthood. The separated whose fathers were manual workers were less likely to be upwardly mobile from paternal occupation category to higher categories of own occupation, education, and incomes. The separated whose fathers had junior and senior clerical occupations were more likely to be downwardly mobile. Comparison of trajectories of incomes across adulthood showed that the difference between the separated and the non-separated grew larger across time, such that among the separated the incomes decreased.

Conclusions. This life-course study shows that severe ELS due to a separation from parents in childhood is associated with socio-economic disadvantage in adult life. Even high initial SEP in childhood may not protect from the negative effects of ELS.

| Abbreviations | ||

| AOR | = | adjusted odds ratio |

| ELS | = | early life stress |

| HBCS | = | Helsinki Birth Cohort Study |

| SEP | = | socio-economic position |

Key messages

Early life stress (ELS) may determine the course of socio-economic position (SEP) in adulthood, which is a powerful source of health inequality.

Even a higher initial SEP in childhood may not override the effects of ELS in adult life.

The results may help to understand the accumulation of health inequality: Experience of ELS for various reasons, such as child abuse and neglect, illness, poverty, institutionalization, immigration, or war, still concerns children everywhere in the contemporary world.

Introduction

Inter-generational social mobility refers to transition of an individual from the parental social position to another social position in adult life. Socio-economic position (SEP) and inter-generational social mobility are known to be powerful determinants of health, illness, and mortality. However, relative to the wealth of studies showing how SEP may function either as the source or the consequence of health inequality (Citation1–5), far less attention has been paid to the early life determinants of adult SEP and inter- generational social mobility. While there exists a strong inheritance of SEP between parents and their children (Citation6), early life determinants, such as intelligence (Citation7–10), academic skills (Citation6), behavior problems, and belief in own ability to control events (Citation10,Citation11), may act as potential mechanisms in determining adult SEP.

An early life determinant that, to our knowledge, has not been previously tested against adult SEP and inter-generational social mobility is the experience of severe early life stress (ELS), arising for instance from parental abuse, neglect, and separation from parents owing to parental death, illness, imprisonment, or child institutionalization or adoption. Prospective evidence suggests that ELS is associated with poorer intellectual ability and school achievement (Citation12,Citation13), altered function of the stress-related biological feedback systems (Citation14–18), increased risk for mental disorders (Citation19–23), health problems (Citation24,Citation25), and reduced physical growth (Citation26).

We examined whether ELS is associated with adulthood SEP irrespective of childhood SEP and hypothesized that ELS has a negative effect on 1) highest attained occupation, education, and taxable incomes from early to late adulthood; 2) trajectories of incomes across the entire working career in adulthood. Next, we tested, separately in each childhood SEP category, 3) whether ELS has a negative influence on inter-generational social mobility from childhood SEP to adult SEP. ELS was defined as a separation from both parents in childhood for an average period of 1.7 years, at an average age of 4.7 years during World War II, when the Finnish government evacuated children, unaccompanied by their parents, from voluntary families with various SEPs to temporary foster care abroad, mainly in Sweden.

Materials and methods

Participants

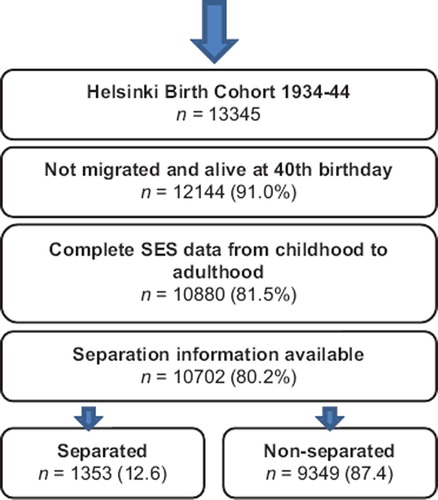

The outline of the Helsinki Birth Cohort Study (HBCS) (Citation27,Citation28) is illustrated in . Of the 13,345 cohort members, we excluded 1,008 individuals who emigrated and 193 individuals who died before their 40th birthday. We also excluded 1,264 members without complete SEP available and 178 with an unclear separation status (1.3%) (Citation29). We had complete data available on 10,702 individuals (80.2% of the initial study population): women (n = 5,113) and men (n = 5,589).

The included participants were 0.3 (95% confidence interval (CI) −0.4, −0.2) years younger than those excluded. Compared to non-separated participants, it was more likely for the separated to be excluded (odds ratio (OR) 1.5; 95% CI 1.3, 1.6) as they were more likely to have emigrated before their 40th birthday (OR 2.0; 95% CI 1.7, 2.3). It was also more likely that the separated did not have complete SEP information from childhood and adulthood available (OR 1.5; 95% CI 1.3, 1.7). The HBCS has been approved by the Ethics Committee of the National Public Health Institute. Register data were linked with permission from the Finnish Ministry of Social Affairs and Health, the Finnish National Archives, and Statistics Finland.

Separation

During World War II, Finland fought two wars with the Soviet Union. To protect the Finnish children from the strains of war, children from various SEPs were evacuated abroad, mainly Sweden and Denmark, unaccompanied by their parents. Since the evacuations were voluntary, the likelihood of a Finnish child being evacuated was influenced by an unpredictable interplay between political and familial factors (Citation28,Citation30,Citation31). The Finnish National Archives preserves full documentation of the 48,628 evacuated children, from which we identified 1,353 participants of the HBCS. The register also carries information on age at separation (M 4.7 years; SD 2.4 years) and length of the separation (M 1.7 years; SD 1.0 years), available for 1,220 (90.2%) and 1,190 (88%) of the separated HBCS participants, respectively.

Table I. Descriptive statistics according to the separation status.

Socio-economic variables in childhood and in adulthood

We defined childhood SEP based on the highest occupational status of the father, obtained from birth, child welfare clinic, and school health care records. Father's occupation was grouped according to the classification system of Statistics Finland (Citation32), based on international standards. The first phase of classification used seven categories (1 = self- employed; 2 = upper-level employees with administrative, managerial, professional, and related occupations; 3 = lower-level employees with administrative and clerical occupations; 4 = manual workers; 5 = students; 6 = pensioners; and 7 = others). We used here the three main categories of these (categories 2, 3, 4, coded as: manual workers = 1; junior clerical = 2; and senior clerical = 3) and omitted other categories representing only a minority of the participants. Self-employed were omitted because of their heterogeneous professions (ranging from shoe-polishers to owners of enterprises of all sizes).

Data on SEP in adulthood were obtained from Statistics Finland, where information on educational attainment, occupational status, and taxable incomes are available at an individual level at 5-year intervals between 1970 and 2000. Thus, for the youngest in the cohort the follow-up period covered the time in ages 26 to 56 and for the oldest in the cohort the time in ages 36 to 66. We used the maximum educational attainment and occupational status for each subject when defining adult SEP. Occupation was grouped into three categories (Citation32) corresponding to the categories of father's occupation (1 = manual workers; 2 = junior clerical; 3 = senior clerical). Education was grouped into three categories based on the UNESCO international standard classification of education such that 1 = Basic or Upper secondary, 2 = Lower tertiary, and 3 = Higher tertiary (Citation33). The taxable incomes were first log-transformed due to their skewed distribution and then standardized separately at each data collection point by sex. We used these standardized values to define the maximum income level during adulthood and then split the maximum values into tertiles by sex (1 = lowest; 2 = intermediate; 3 = highest tertile). If the participant was retired at a specific data collection point, his/her incomes at that point were not included in the standardization. Given that the oldest cohort members were 66 years old in year 2000, there were 3,231 retired participants at that point.

To obtain further information on SEP in childhood, we used variables derived from school and child welfare records on the number of rooms in each childhood household, and the density of its inhabitants (number of people living in the same household per available room). This information was available on 9,726 (90.9%) and 9,039 (84.5%) cohort members, respectively.

Social mobility

In the social mobility analyses, we used three-level hierarchies in all SEP variables (1 = low; 2 = intermediate; 3 = high). Social mobility was defined as change in this three-level hierarchy from paternal occupation to adult occupation, educational attainment, or income. This yielded three nominal mobility variables, from 1) childhood SEP to adult occupation, from 2) childhood SEP to adult educational attainment, and from 3) childhood SEP to adult taxable incomes, where stability was coded as 0, mobility upward from childhood manual worker or junior clerical SEP as 1, and mobility downward from childhood senior or junior clerical SEP as 2. Stability refers to maintaining the initial hierarchy level (low, intermediate, high) from childhood to adulthood.

Statistical analyses

We used logistic regression analyses to test if separation was associated with adult SEP (the lowest adult SEP category as the referent), controlling for father's occupational status in childhood, sex, birth order, and year of birth. Next, we used multinomial logistic regression analyses to examine whether the likelihood of social mobility either upward or downward varied by separation status, with the category of stable SEP from childhood to adulthood as the referent. Analyses on mobility were stratified by childhood SEP categories adjusting for sex, birth order, and year of birth.

Trajectories of incomes, i.e. the sex-specific z scores of taxable incomes across the entire working career in adulthood measured at 5-year intervals between years 1970 and 2000, were analyzed with linear mixed model analyses. Whether or not the trajectories of incomes across time varied between the separated and non-separated was determined by including an interaction term ‘separation status × year of measurement’ in the models. These models were adjusted for sex, father's occupation, birth order, and year of birth. We also tested if any of the associations of separation status with adult SEP and inter-generational social mobility were moderated by sex, by including an interaction term ‘separation status × sex’ in the regression equation/mixed model analysis.

Results

Initial analyses

shows that the separated were more likely to be higher in birth order and to have a lower childhood SEP based on father's occupational status. They lived in households with fewer rooms and more inhabitants per room. The separated were also, on average, 2 years older when the census data were first collected in year 1970.

Not surprisingly, father's low SEP was strongly associated with fewer rooms in the contemporary household and higher density of inhabitants. Of those whose father had a low, intermediate, and high occupational status, 92.1%, 83.8%, and 40.8% lived in a household with 1–2 rooms, respectively. In the lowest class of father's occupation, 59.3% lived in a household with 3 or more individuals per available room, while in the intermediate and higher occupational categories 41% and 20.5% lived in households with 3 or more individuals per available room, respectively.

Given that the separated were more likely to emigrate before their 40th birthday, we also examined whether the risk for emigration was associated with father's occupational status in childhood and own educational attainment in adulthood. Father's occupation in childhood and own adult occupation were not significantly associated with emigration status in the entire study population, nor when examined separately in non-separated and separated participants.

Separation status and highest attained SEP in adulthood

shows the percentages of the separated and the non-separated in categories of adult SEP, and adjusted odds ratios (AORs) and the 95% CIs from the logistic regression analyses predicting the highest attained SEP in adulthood from the childhood separation status. Compared to the non-separated, the separated were more likely to have attained a lower occupational status, a lower educational level, and lower income in adulthood, adjusting for father's occupational status, sex, year of birth, and birth order. Sex did not moderate these associations.

Table II. Adjusted odds ratios (AORs) and 95% confidence intervals predicting adult occupation, educational attainment, and income from childhood separation status, using the lowest SEP category as the referent. The numbers (n) represent raw figures of separated and non-separated participants in each adult SEP category.

Social mobility in separated and non-separated participants

As shows, the separated whose fathers were manual workers were less likely to be upwardly mobile (own highest achieved occupation, educational attainment, and income), compared to the non-separated. In addition, the separated whose fathers were in junior clerical occupations were more likely to be downwardly mobile. The separated whose fathers were in senior clerical occupations were more likely to be downwardly mobile. Sex did not moderate these associations.

Table III. Social mobility in separated and non-separated participants stratified by childhood SEP as assessed by father's occupational category.

Trajectories of taxable incomes across the entire working career in separated and non-separated participants

shows the trajectories of adult incomes from year 1975 to 2000. shows that the difference in taxable incomes between separated and non-separated grew larger across time, even though the initial level of taxable incomes in 1970 was already lower for the separated (-0.06; 95% CI -0.10, -0.02; P < 0.007; P < 0.001 for ‘separation status × time in 5-year intervals’). –D present the trajectories in each category of childhood SEP (P < 0.001 for ‘separation status × time in 5-year intervals × childhood SEP’). The difference between non-separated and separated was largest in the group whose fathers were manual workers (P < 0.001 for ‘separation status × time in 5-year intervals’; ). Thereby, when the father was junior clerical (P < 0.03 for interaction; ) the difference between the groups grew big only in 1990, when Finland entered in a severe economic recession. In the highest childhood SEP category (senior clerical; P < 0.14 for interaction; ), the separated earned even more in the first 15 years of the follow-up, but declined thereafter below the incomes of non-separated, the turning point also being in year 1990.

Figure 2. The trajectories of adult incomes from 1975 to 2000 in the entire population (A), and stratified by the childhood SEP (Figure B = manual worker, Figure C = junior clerical, and Figure D = senior clerical). The standardization is done separately for men and women, and the trajectories are adjusted for year of birth and birth order. Dashed line represents non-separated, and solid line the group of separated.

Discussion

This life-course study, spanning from birth across the entire work career in adulthood, showed that ELS is associated with socio-economic disadvantage in adult life. Firstly, the separated attained a lower SEP in adulthood, as indicated by their own highest attained occupational status, educational level and taxable incomes, compared to the non-separated. These associations persisted after controlling for father's occupational status in childhood, sex, year of birth, and birth order. Secondly, we found that the inter-generational social mobility was associated with the separation. Compared to the non-separated participants, the separated participants whose fathers had a manual worker occupation were less likely to be upwardly mobile, and those who had fathers in junior clerical and senior clerical occupations were more likely to be downwardly mobile.

The income trajectories across the working career in adulthood, from year 1970 to year 2000, showed that the differences between the separated and non-separated participants were evident throughout adulthood, such that the group differences grew larger with years passing by, with the separated displaying a decrease in the taxable incomes. When stratified according to the initial childhood SEP, the difference was most marked among participants in the lowest SEP. However, also separated participants with fathers in junior and senior clerical occupations had different income trajectories; whereas in the first 15 years there were no marked differences, the separated having even higher incomes in the highest childhood SEP group, the income differences enlarged thereafter in favor of the non-separated. The turning-point for lower incomes in these groups was in year 1990 when Finland entered economic recession. Our results therefore suggest that even a high initial SEP in childhood may not override the effects of ELS in adult life.

These findings add to the previous literature in several ways. First, the results clearly convey a message that in addition to parental inheritance of SEP, other environmental factors, such as an experience of severe ELS, may have long-term consequences for adult SEP. Importantly, we observed these consequences in relation to all indices of adult SEP, i.e. own occupation, educational attainment, and income, all of which are suggested to associate with differential health consequences (Citation34). The found associations were similar in men and women.

While similar studies do not exist, there is evidence that lower intelligence level (Citation7–10), poorer academic skills (Citation6), behavior problems, and lack of locus of control (Citation10,Citation11) influence negatively adult socio-economic attainment and inter-generational social mobility. In addition, there is evidence that disruption in the family structure (e.g. divorce) is associated with comparable outcomes as reported here. For instance, Biblartz et al. (Citation35) showed that men from disrupted family backgrounds had a greater likelihood to have attained lower as opposed to higher occupational status, after controlling for the father's SEP. In addition, family disruption weakened the inter-generational inheritance of occupational status. Fischer (Citation36) in turn reported that parental divorce had a negative impact on children's educational attainment but not on occupational status. However, the effects were dependent on the economic resources of the mother: if the mother had a high level of economic resources, indicating an ability to compensate the loss, no divorce effect was found (Citation36). However, divorce may not be an equally severe ELS factor for all children, given that longitudinal studies have reported only weak effects of divorce on subsequent development (Citation37).

In contrast, the effects of severe ELS on subsequent life may be extensive. Prior evidence shows that ELS is likely to be associated with lower level of intelligence (Citation12), mental and physical health adversity (Citation38), and structural changes of the central nervous system (Citation39). Consistently with these findings, we have previously reported that the separated display more depressive symptoms (Citation28,Citation31), severe mental disorders (Citation40), and their risk for type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease are increased (Citation24). We have also shown that their hormonal reactivity to stress is higher in late adulthood, compared to the non-separated (Citation17). Indeed, all these characteristics provide potential mechanisms that may mediate the link between ELS and adult SEP and thus explain how ELS translates into socio-economic adversity in adulthood. Importantly, the effects of ELS on SEP were not limited to the group with low SEP in childhood, which is also known to be a risk for somatic and mental health problems in adulthood (Citation1–4).

Studying the effects of ELS on subsequent life is mostly based on natural experiment designs. This implies that there remains always a possibility for confounders that cannot be addressed, causing the effects of ELS to be subordinate to other, unknown life circumstances that caused the ELS itself. While this possibility can be ruled out only by applying randomized control trials, ethical reasons restrict their use in human ELS studies, with the exception of intervention studies, which are few (Citation23,Citation41). Several other limitations are also apparent. Our measure of childhood SEP was limited to paternal occupational status and did not incorporate other indicators of social inequality. Given that the fathers also served in the armed forces during the years of war, their own socio-economic attainment may have been compromised due to these circumstances. However, we derived paternal occupation from birth, child welfare clinic, and school records, which are objective records and free of recall bias. We also used only the highest of all three indicators in the social mobility analyses, in order to be sensitive to the highest ranking in defining the origins of SEP. To validate father's occupation, we also compared father's occupation to childhood census data of the rooms available in each childhood household and the density of inhabitants in the household, and observed high correspondence between these measures. Second, we cannot be certain that the initial selection of weaker/less healthy children to temporary foster care would not have confounded our results. However, as we have argued before (Citation31), we have not been able to identify any systematic pattern in the selection of children. Many families chose, for example, to send only one of their children away. In some families, the decision might have favored the strongest or the oldest of the children, whereas some families may have favored the youngest or the sickest. Third, there was an emigration wave from Finland to Sweden during the 1960s and 1970s, due to better work opportunities in the expanding Swedish economy. Not surprisingly, compared to non-separated individuals of the HBCS, there was an increased likelihood that the former child evacuees emigrated. Due to their long stay in Sweden in their childhood, many of them had the advantage of speaking Swedish fluently, and they also may have retained contact with their former foster families. We then acknowledge the possibility that the emigration process may have biased our findings. This would be the case, for instance, if participants with more potential to move upward in the social hierarchy had emigrated, and that would concern specifically the former evacuees. However, childhood and adulthood SEP were not significantly associated with emigration, neither in non-separated nor separated, thus this kind of confounding seems unlikely. Finally, the age and duration categories applied in the present study included uneven numbers of subjects, and thus the power to detect significant age and duration effects varied between the categories. Unfortunately, we do not have data on the quality of foster care, nor of the care given at the biological home, both of which are likely to modulate the effect of ELS on adult SEP.

Contrary to many other Western societies, in Finland the change from an agrarian society to an industrialized one occurred within two decades after WW II. It should be taken into account that the rapid urbanization may have offered a special time window for a relatively large social mobility. On the other hand, there is evidence showing that the absolute social mobility, referring to the percentage of the cohort in a class position different from that of their parents, people moving up or down, has not decreased in younger Finnish cohorts (Citation42). Further, if we compare the absolute social mobility of the HBCS participants (67% in men and 74% in women) to one reported from population-based samples of the same age-group (77% for men and 85% for women) (Citation42), we observe slightly less mobility in our cohort. This may be due to the fact that the parents of the HBCS were already urban, and, given that the birth hospitals were communal, there was a slight over-representation of the lowest end of the socio-economic distribution in the HBCS.

In conclusion, this study presents evidence of long-term socio-economic disadvantage following the experience of ELS. Although the historical circumstances in this study were exceptional, the developmental significance of ELS is not bound to this study. Experience of ELS for various reasons, such as child abuse and neglect, illness, poverty, institutionalization, immigration, or war, still concerns children everywhere in the contemporary world.

Declaration of interest: This work was supported by the Academy of Finland, the European Science Foundation (EuroSTRESS), the Päivikki and Sakari Sohlberg Foundation, the Finnish Diabetes Research Foundation, the Finnish Foundation for Cardiovascular Research, the Finnish Foundation for Pediatric Research, the Finnish Medical Society Duodecim, Yrjö Jahnsson Foundation, Juho Vainio Foundation, Signe and Ane Gyllenberg Foundation, Samfundet Folkhälsan, the Emil Aaltonen Foundation, and Finska Läkaresällskapet. The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Kauhanen L, Lakka HM, Lynch JW, Kauhanen J. Social disadvantages in childhood and risk of all-cause death and cardiovascular disease in later life: a comparison of historical and retrospective childhood information. Int J Epidemiol. 2006;35:962–8.

- Ljung R, Hallqvist J. Accumulation of adverse socioeconomic position over the entire life course and the risk of myocardial infarction among men and women: results from the Stockholm Heart Epidemiology Program (SHEEP). J Epidemiol Community Health. 2006;60:1080–4.

- Lynch JW, Kaplan GA, Shema SJ. Cumulative impact of sustained economic hardship on physical, cognitive, psychological, and social functioning. N Engl J Med. 1997;337: 1889–95.

- Poulton R, Caspi A, Milne BJ, Thomson WM, Taylor A, Sears MR, . Association between children's experience of socioeconomic disadvantage and adult health: a life-course study. Lancet. 2002;360:1640–5.

- Tiffin PA, Pearce MS, Parker L. Social mobility over the lifecourse and self reported mental health at age 50: prospective cohort study. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2005; 59:870–2.

- Harper B, Haq M. Occupational attainment of men in Britain. Oxf Econ Pap. 1997;49:638–50.

- Deary IJ, Taylor MD, Hart CL, Wilson V, Smith GD, Blane D, . Intergenerational social mobility and mid-life status attainment: Influences of childhood intelligence, childhood social factors, and education. Intelligence. 2005;33: 455–72.

- Savage M, Egerton M. Social mobility, individual ability and the inheritance of class inequality. Sociology. 1997;31:645–72.

- Strenze T. Intelligence and socioeconomic success: A meta-analytic review of longitudinal research. Intelligence. 2007;35:401–26.

- von Stumm S, Gale CR, Batty GD, Deary IJ. Childhood intelligence, locus of control and behaviour disturbance as determinants of intergenerational social mobility: British Cohort Study 1970. Intelligence. 2009;37:329–40.

- Colom R, Escorial S, Shih PC, Privado J. Fluid intelligence, memory span, and temperament difficulties predict academic performance of young adolescents. Pers Individ Dif. 2007;42:1503–14.

- Nelson CA 3rd, Zeanah CH, Fox NA, Marshall PJ, Smyke AT, Guthrie D. Cognitive recovery in socially deprived young children: the Bucharest Early Intervention Project. Science. 2007;318:1937–40.

- Odenstad A, Hjern A, Lindblad F, Rasmussen F, Vinnerljung B, Dalen M. Does age at adoption and geographic origin matter? A national cohort study of cognitive test performance in adult inter-country adoptees. Psychol Med. 2008;38:1803–14.

- Gunnar MR, Frenn K, Wewerka SS, Van Ryzin MJ. Moderate versus severe early life stress: associations with stress reactivity and regulation in 10–12-year-old children. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2009;34:62–75.

- Heim C, Mletzko T, Purselle D, Musselman DL, Nemeroff CB. The dexamethasone/corticotropin-releasing factor test in men with major depression: role of childhood trauma. Biol Psychiatry. 2008;15:398–405.

- Heim C, Newport DJ, Heit S, Graham YP, Wilcox M, Bonsall R, . Pituitary-adrenal and autonomic responses to stress in women after sexual and physical abuse in childhood. JAMA. 2000;284:592–7.

- Pesonen A-K, Räikkönen K, Feldt K, Heinonen K, Osmond C, Phillips DI, . Childhood separation experience predicts HPA axis hormonal responses in late adulthood: A natural experiment of World War II. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2010;35:758–67.

- Tyrka AR, Wier L, Price LH, Ross N, Anderson GM, Wilkinson CW, . Childhood parental loss and adult hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal function. Biol Psychiatry. 2008;63:1147–54.

- Hjern A, Lindblad F, Vinnerljung B. Suicide, psychiatric illness, and social maladjustment in intercountry adoptees in Sweden: a cohort study. Lancet. 2002;360:443–8.

- Veijola J, Läärä E, Joukamaa M, Isohanni M, Hakko H, Haapea M, . Temporary parental separation at birth and substance use disorder in adulthood. A long-term follow-up of the Finnish Christmas Seal Home Children. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2008;43:11–17.

- Veijola J, Mäki P, Joukamaa M, Läärä E, Hakko H, Isohanni M. Parental separation at birth and depression in adulthood: a long-term follow-up of the Finnish Christmas Seal Home Children. Psychol Med. 2004;34:357–62.

- von Borczyskowski A, Hjern A, Lindblad F, Vinnerljung B. Suicidal behaviour in national and international adult adoptees: a Swedish cohort study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2006;41:95–102.

- Zeanah CH, Egger HL, Smyke AT, Nelson CA, Fox NA, Marshall PJ, . Institutional rearing and psychiatric disorders in Romanian preschool children. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166:777–85.

- Alastalo H, Räikkönen K, Pesonen AK, Osmond C, Barker DJ, Kajantie E, . Cardiovascular health of Finnish war evacuees 60 years later. Ann Med. 2009;41:66–72.

- Bentley T, Widom CS. A 30-year follow-up of the effects of child abuse and neglect on obesity in adulthood. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2009;17:1900–5.

- Grimard F, Laszlo S. Long term effects of civil conflict on women's health outcomes in Peru. 2010 [updated 2010; cited]. Available at: http://www.mcgill.ca/files/economics/Peru_May2010.pdf. Accessed 1.8.2010.

- Barker DJ, Osmond C, Forsen TJ, Kajantie E, Eriksson JG. Trajectories of growth among children who have coronary events as adults. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:1802–9.

- Pesonen A-K, Räikkönen K, Heinonen K, Kajantie E, Forsén T, Eriksson JG. Depressive symptoms in adults separated from their parents as children: a natural experiment during World War II. Am J Epidemiol. 2007;166:1126–33.

- Pesonen A-K, Räikkönen K, Kajantie E, Heinonen K, Henriksson M, Leskinen JT, . Childhood traumatic separation experience predicts poorer intellectual ability in young men. Submitted.

- Kavén P. 70 000 pientä kohtaloa. Helsinki: Otava; 1985.

- Pesonen A-K, Räikkönen K, Heinonen K, Kajantie E, Forsén T, Eriksson JG. Pesonen et al. respond to ‘The life course epidemiology of depression’. Am J Epidemiol. 2007; 166:1138–9.

- Statistics Finland. Classification of socio-economic groups. 1989 [updated 1989; cited]. Available at: http://www.stat.fi/meta/luokitukset/sosioekon_asema/001-1989/33.html. Accessed 1.8.2010.

- UNESCO. International Standard Classification of Education ISCED. 1997 [updated 1997 cited]. Available at: http://www.unesco.org/education/information/nfsunesco/doc/isced_1997.htm. Accessed 1.8.2010.

- Geyer S, Hemstrom O, Peter R, Vagero D. Education, income, and occupational class cannot be used interchangeably in social epidemiology. Empirical evidence against a common practice. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2006; 60: 804–10.

- Biblartz TJ, Raftery AE. The effects of family disruption on social mobility. Am Sociol Rev. 1993;58:97–109.

- Fischer T. Parental divorce and children's socio-economic success: conditional effects of parental resources prior to divorce, and gender of the child. Sociology. 2007;41:475–95.

- Amato PR. Children of divorce in the 1990s: an update of the Amato and Keith (1991) meta-analysis. J Fam Psychol. 2001;15:355–70.

- McEwen BS. Physiology and neurobiology of stress and adaptation: central role of the brain. Physiol Rev. 2007;87: 873–904.

- Murgatroyd C, Patchev AV, Wu Y, Micale V, Bockmuhl Y, Fischer D, . Dynamic DNA methylation programs persistent adverse effects of early-life stress. Nat Neurosci. 2009;12:1559–66.

- nRäikkönen K, Lahti M, Heinonen K, Pesonen A-K, Wahlbeck K, Kajantie E, . Risk of severe mental disorders in adults separated temporarily from their parents in childhood: The Helsinki birth cohort study. J Psychiatr Res. 2010 Jul 24 (Epub ahead of print).

- Marshall PJ, Reeb BC, Fox NA, Nelson CA III, Zeanah CH. Effects of early intervention on EEG power and coherence in previously institutionalized children in Romania. Dev Psychopathol. 2008;20:861–80.

- Erola J. Social mobility and education of Finnish Cohorts born 1936–75: succeeding while failing equality of opportunity? Acta Sociologica. 2009;52:307–27.