Abstract

Lacosamide is a third-generation antiepilepsy drug approved for adjunctive treatment of partial-onset seizures in adults. The pharmacology of lacosamide includes linear kinetics, complete bioavailability, and no major drug interactions. Lacosamide produces slow inactivation of neuronal sodium channels, which differentiates it from other sodium channel modulators, such as carbamazepine and phenytoin. The drug was effective with no major safety problems detected in three large placebo-controlled pivotal trials and has been released in Europe and the US at 200–400 mg/day, divided b.i.d.; an intravenous formulation is approved for temporary conversion from oral therapy. This article reviews the clinical development, pharmacology, and uses of lacosamide for treating partial-onset seizures in adults.

Key words::

Key messages

Lacosamide is an antiepileptic drug (AED) approved in the EU and US for adjunctive treatment for partial-onset seizures in patients 16 years or older (Europe) or 17 years or older (US).

Lacosamide exerts its therapeutic activity by causing slow inactivation of neuronal sodium channels, a mechanism distinct from fast sodium channel activating AEDs like carbamazepine and lamotrigine.

Lacosamide demonstrates linear kinetics, nearly 100% bioavailability, with a half-life of approximately 13 hours, and no major pharmacokinetic drug–drug interactions.

The tolerability and efficacy of lacosamide was established in patients with medically resistant partial-onset seizures in three randomized, placebo-controlled trials (N = 1,294).

Common adverse events in adjunctive trials with lacosamide were dizziness, nausea, blurred vision and imbalance. These symptoms were generally transient and were most common during dose titration. Approximately 14% of patients discontinued treatment due to adverse events during the controlled clinical trials.

Lacosamide is available for iv use – the 10 mg/mL solution is bioequivalent to 200 mg oral dosing when infused over 30 or 60 minutes. It is indicated as temporary substitute when oral dosing is not feasible.

Introduction

Lacosamide was approved for the adjunctive treatment of partial-onset seizures in Europe and the US in 2008–2009. An expanding number of antiepilepsy drugs (AEDs) are available for treating partial-onset epilepsy (); however, approximately one-third of patients continue to have seizures despite treatment with first- and second-line AEDs; lacosamide was tested in these patients with medically resistant epilepsy (Citation1–3). This article reviews the pharmacologic and clinical properties of oral and intravenous (iv) lacosamide, including its efficacy, safety, and tolerability profile, compared to other AEDs.

Table I. Antiepileptic medications by generations.

Lacosamide, initially named harkoseride and SPM 927, is an analog of the amino acid L-serine (Citation4–6). It was identified as a potential AED in animal seizure screening protocols (Citation4). These models demonstrated a potential effectiveness against partial-onset seizures (maximal electro-shock model), drug-resistant partial-onset seizures (the 6 Hz electrical stimulation model), and status epilepticus (cobalt/homocysteine and electrical status epilepticus models). Lacosamide had mixed results in models of generalized epilepsy, with no reduction of absence seizures in the Wag/Rij rodent model and inhibition of seizures triggered by iv but not subcutaneous pentylenetetrazol (PTZ) (Citation7). In isobolographic analysis using the 6 Hz seizure model in mice, the effect of lacosamide in combination with carbamazepine, lamotrigine, topiramate, gabapentin, or levetiracetam was supra-additive; additive effects were shown when lacosamide was combined with phenytoin or valproate (Citation8). Based on several successful phase II and large phase III placebo-controlled, randomized trials, lacosamide was approved in the EU and US for adjunctive treatment for partial-onset seizures in patients 16 years or older (Europe) or 17 years or older (US). Lacosamide is approved at total oral daily doses (TDD) of 200–400 mg, with large amounts of safety data collected at 600 mg TDD and smaller numbers of patients treated with doses 700–800 mg TDD. An oral solution of lacosamide 10 mg/mL and 15 mg/mL was approved in the US and Europe, respectively. An iv solution was approved as a temporary substitute for oral treatment, and an iv loading trial showed lacosamide was tolerated with rapid infusions of 200–300 mg (Citation9). Lacosamide's possible uses in monotherapy, for treating children, and for treating generalized epilepsy are currently being evaluated.

Mechanisms and pharmacology

Lacosamide blocks long-duration (several hundred milliseconds) neuronal burst trains by causing slow inactivation of neuronal sodium channels. This mechanism increases neuronal depolarization thresholds through a mechanism distinct from fast sodium channel activating AEDs like carbamazepine and lamotrigine (Citation10,Citation11). The pharmacology of lacosamide is straightforward (): linear kinetics, nearly 100% bioavailability, half-life approximately 13 hours, and no major pharmacokinetic drug–drug interactions identified. Lacosamide is partially metabolized by cytochrome enzyme CYP2C19; however, 40% of the administered dose is eliminated unchanged, which limits influences of drug interactions on its elimination. Lacosamide did not have interactions with carbamazepine and divalproex in specific studies and did not have significant interactions with other AEDs in pooled pharmacokinetic studies performed in large clinical trials (Citation12,Citation13). Additionally, after correcting for body mass, small pharmacology studies showed that lacosamide dose–concentration relationships are not altered by patients’ gender, age, or ethnic origin and were not altered by mild to moderately impaired renal function, partially impaired hepatic function, or by hepatic CYP450 polymorphisms. Lacosamide does not significantly alter concentrations of oral contraceptives ethinyl estradiol and levonorgestrel and, therefore, is unlikely to interfere with contraceptive protection (Citation12).

Table II. Pharmacokinetic profile of lacosamide.

Clinical overview

Efficacy

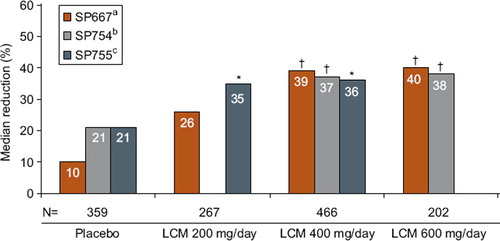

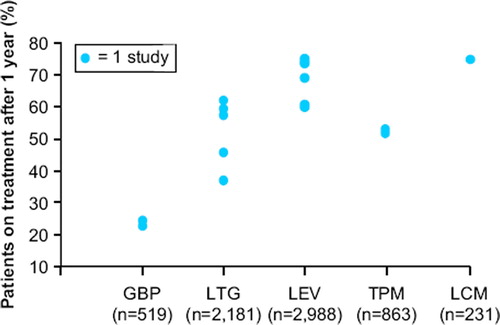

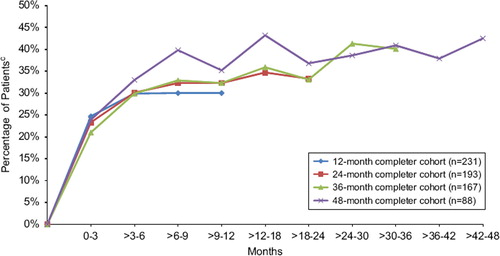

The tolerability and efficacy of lacosamide was studied in patients with medically resistant partial-onset seizures in one phase II and two phase III randomized, placebo-controlled trials that enrolled 1,294 patients who received lacosamide treatment. Patients had significant reductions in monthly seizure frequency—after subtracting placebo responses, this averaged 15% for lacosamide 200 mg TDD, 16%–28% for lacosamide 400 mg TDD, and 17%–21% for lacosamide 600 mg TDD (Citation14–16). Overall reductions in seizure frequencies ranged from 26% to 39% across a dose range of 200–400mg TDD (divided twice a day) (). The proportion of treatment responders (those with >50% seizure reduction) paralleled changes in seizure frequency (Citation14–16). Patients with secondary generalized tonic clonic seizures had particularly high reduction in seizures. Median reductions in secondary generalized seizures were: 50% for lacosamide 200 mg TDD, 56% for 400 mg TDD, and 86% for 600 mg TDD (Citation17). Lacosamide 600 mg TDD was effective compared to placebo in two large trials; however, efficacy was similar to 400 mg TDD in the intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis and since several CNS-related side-effects, particularly dizziness, were increased compared to lower doses, this dose was not approved in the EU and US. The long-term retention rates and efficacy for patients treated with lacosamide in an open-label extension study remained high and at 1 year of treatment was comparable to levetiracetam and other marketed AEDs (). Though less than 10% of patients became seizure-free in controlled trials, approximately 20%–30% had >75% reduction in seizures (). Treatment effects for primary generalized epilepsy—absence, myoclonic and primary tonic clonic seizure types—have not been explored. Pediatric uses also remain to be evaluated. Oral lacosamide therapy was effective for medically resistant non-convulsive status epilepticus in a recent case series (Citation18).

Figure 1. Median percent reduction in seizure frequency per 28 days: Baseline to maintenance, per randomized dose. Note: lacosamide 600 mg/day is above the approved dose.*P < 0.05; †P < 0.01; P values based on log-transformed data from pairwise treatment using ANCOVA models. (LCM = lacosamide; ITT = intent-to-treat (randomized subjects receiving at least one dose of trial medication with ≥1 post-base-line efficacy assessment)).

aBen-Menachem E, et al. Epilepsia. 2007;48:1308–1317.

bChung S, et al. Epilepsia. 2010;51:958–967.

cHalasz P, et al. Epilepsia. 2009;50:443–453.

Figure 2. Retention rates for open-label long-term studies. (GBP = gabapentin; LTG = lamotrigine; LEV = levetiracetam; TPM = topiramate; LCM = lacosamide). Adapted from: Zaccara G, et al. Acta Neurol Scand. 2006;114(3)157–168; McCormack PL, Robinson DM. CNS Drugs.2009;23(1):71–79; and Husain A, et al. Epilepsia. 2011;52(Suppl. 6):155, abs. p503.

Figure 3. Percentage of patients with ≥75% reduction responsea in seizure frequency over time by yearly completer cohort in open-label extension trial SP756b (lacosamide dose 100–800 mg/day). Note: lacosamide 600 mg/day is above the approved dose. aResponders were defined as patients with at least a 75% reduction in seizure frequency during the time interval specified from Baseline of trial SP754 (NCT00136019) (Chung S et al. Epilepsia. 2010;51:958–967.) bTrial SP756(NCT00522275) is the open-label extension of trial SP754. cPercentages based on the number of patients in the completer cohort group with an evaluable responder status during the specified tiem interval Figure adapted from: Husain A, et al. Epilepsia. 2011;52(Suppl. 6):155, abs. p503. This figure was updated in December 2011.

Tolerability/safety profile

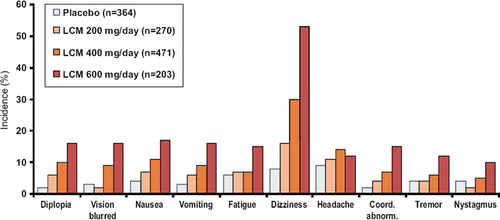

The most common adverse events in adjunctive trials with lacosamide were CNS-related symptoms and signs, particularly dizziness, nausea, blurred vision, and imbalance (). These symptoms were generally transient and were most common during dose titration. Approximately 14% of patients discontinued treatment due to adverse events during the controlled clinical trials—most due to CNS-related symptoms. Larger proportions of patients discontinued treatment at higher doses: 28.6% discontinued 600 mg/day lacosamide treatment due to treatment-emergent adverse events, compared with 17.2% taking 400 mg/day and 9.6% taking 200 mg/day (Citation14–16). This contributed to 200 mg/day and 400 mg/day lacosamide doses and not 600 mg TDD being approved for treating partial-onset seizures. Lacosamide treatment was well tolerated during long-term treatment (current data available up to 8 years).

Figure 4. Incidence of AEs during treatment*. Note: lacosamide 600 mg/day is above the approved dose. Adapted from Biton V, et al. Epilepsia 2009;50(Suppl4):110, Abs T230. *Treatment phase = Titration plus maintenance phase. SS = Safety set: subjects who received at least one dose of trial medication. Phase II/III registration trials SP667, SP754, SP755. This figure was updated in December 2011 .

Several adverse events of particular importance for patients with epilepsy were not increased significantly with lacosamide treatment; these included somnolence, cognitive side-effects, weight gain or loss, and rash: 7.2% of patients randomized to lacosamide and 4.7% taking placebo experienced somnolence, 2.3% randomized to lacosamide versus 1.6% taking placebo experienced memory impairment, 1.2% randomized to lacosamide versus 0.5% taking placebo experienced weight gain, 2.9% randomized to lacosamide versus 3.0% taking placebo experienced rash (Citation14–16). There was no clinically relevant influence of lacosamide on laboratory results or vital signs in placebo-controlled treatment trials or during longer-term extension treatment.

Similar to several other AEDs, lacosamide treatment was associated with a small increase in the ECG mean PR interval (5–9 ms); however, patients with epilepsy did not develop first-degree heart block (> 200 ms PR interval) with lacosamide treatment. Only one patient in clinical trials had bradycardia detected, and this occurred during an iv infusion with symptoms suggesting a vasodepressor reaction to infusion (Citation14–16).

Intravenous lacosamide studies

Lacosamide is highly soluble and is available in an isotonic solution (10 mg/mL) for iv use. Intravenous lacosamide is bioequivalent to 200 mg oral dosing when infused over 30 or 60 minutes, with a significant increase in peak concentrations with more rapid 15-minute infusions. Two iv lacosamide studies explored conversion from oral to iv treatment: the first study evaluated 60- and 30-minute infusions of 100–300 mg iv divided b.i.d.; a second trial examined longer periods of iv infusion (up to 5 days) with higher doses (200–800 mg divided b.i.d.) and 30-, 15-, or 10-minute infusions. Patients tolerated iv conversion from oral therapy with repeated b.i.d. doses of 100–400 mg (200–800 mg TDD), with the recommended infusion duration of 15 minutes. Less than 10% had adverse events, most commonly headache (7%) or dizziness (6%) (Citation9). There was no significant increase in adverse event frequency or severity based on infusion duration. A recent study showed that patients with partial-onset seizures can safely receive iv loading doses of 200–300 mg given over 15 minutes. The most common side-effects within 4 hours of start of infusion were dizziness (20%) and somnolence (20%) with a 300 mg iv loading dose (Citation19). Adjunctive iv lacosamide was reported to be effective in several patients with refractory status epilepticus; however, this use remains to be explored (Citation20).

Clinical experience in using lacosamide for partial-onset epilepsy

Lacosamide is approved as adjunctive treatment for partial-onset seizures in patients 17 years or older with a titration schedule initiated at 50 mg b.i.d., with weekly dose increases of 50 mg b.i.d. to total daily dosage of 200–400 mg/day. Lacosamide 600 mg TDD was not as well tolerated as lower doses in large clinical trials and was not approved by European and FDA regulators. We, however, have found that individual patients with drug-resistant epilepsy may tolerate lacosamide 500–600 mg TDD without CNS side-effects if the patient is not also receiving high doses of traditional sodium channel modulating AEDs (Citation21). This pharmacodynamic interaction appears to be particularly common with oxcarbazepine but may occur with high doses of lamotrigine, phenytoin, and carbamazepine. In contrast, a post-hoc analysis of pooled pivotal trial data demonstrated that patients on AEDs with non-sodium modulating mechanisms (levetiracetam, divalproex, and topiramate at standard doses) appear generally to tolerate combined therapy with lacosamide well, with a low incidence of treatment-emergent adverse events leading to discontinuation even at 600 mg TDD (Citation22). A recent case series reported increased neurotoxicity (mainly dizziness, imbalance, diplopia, and sedation) in patients taking a concomitant sodium channel AED in comparison to those taking a non-sodium channel AED (Citation23); we find that such pharmacodynamic interaction can be reversed in most patients by reducing their concomitant sodium channel modulating AEDs while rapidly titrating lacosamide to 400–600 mg TDD (Citation21).

Conclusion

Lacosamide is approved for adjunctive treatment of partial-onset seizures in adult patients and is being investigated for treatment of pediatric patients and as monotherapy. It is being clinically evaluated for treatment of acute seizures. It has a unique sodium channel mechanism that appears to differentiate it from traditional AEDs such as oxcarbazepine and phenytoin. Pharmacodynamic interactions, however, often require that other sodium channel AEDs be reduced while titrating lacosamide to effective doses. Additional experience in large treatment populations is needed to verify the favorable safety profile of lacosamide. Lacosamide's safety during pregnancy also remains to be evaluated; optimal doses and titration schedules need also to be explored objectively in trials which do not require fixed doses of previous AEDs.

Declaration of interest: Gregory Krauss is an investigator and consultant for studies funded by UCB Pharma, Eisai Laboratories and Icagen Pharmaceuticals. Gregory Krauss is an investigator for the Epilepsy Research Foundation, the Epilepsy Study Consortium and NINDS. All other authors report no disclosures. UCB Pharma was offered the opportunity to review the medical accuracy of this article. Any changes resulting from comments received were made on the basis of scientific and editorial merit.

References

- Bialer M. New antiepileptic drugs that are second generation to existing antiepileptic drugs. Expert Opin Investig Drugs 2006;15:637–647.

- Kwan P, Brodie M. Early identification refractory epilepsy. N Engl J Med 2000;342:314–319.

- Perucca E. Development of new antiepileptic drugs: challenges, incentives, and recent advances. Lancet Neurol 2007;6:793–804.

- Luszczki JJ. Third-generation antiepileptic drugs: mechanisms of action, pharmacokinetics and interactions. Pharmacol Rep 2009;61:197–216.

- Choi D, Stables JP, Kohn H. Synthesis and anticonvulsant activities of N-benzyl-2-acetamidopropionamide derivatives. J Med Chem 1996;39:1907–1916.

- Choi D, Stables JP, Kohn H. The anticonvulsant activities of functionalized N-benzyl 2-acetamidoacetamides. The importance of the 2-acetamido substituent. Bioorg Med Chem 1996;4:2105–2114.

- Stöhr T, KupferbergHJ, Stables JP . Lacosamide, a novel anti-convulsant drug, shows efficacy with a wide safety margin in rodent models for epilepsy. Epilepsy Res 2007;74:147–154.

- Stöhr T, Shandra P, Kashenko O . Synergism of lacosamide and first-generation and novel antiepileptic drugs in the 6 Hz seizure model in mice (abstract). Epilepsia 2007;48:252.

- Krauss G, Ben-Menachem E, Mameniskiene R Intravenous lacosamide as short-term replacement for oral lacosamide in partial-onset seizures. Epilepsia 2010;51:951–957.

- Errington AC, Stöhr T, Heers C . The investigational anticonvulsant lacosamide selectively enhances slow inactivation of voltage-gated sodium channels. Mol Pharmacol 2008;73:157–169.

- Errington AC, Coyne L, Stöhr L . Seeking a mechanism of action for the novel anticonvulsant lacosamide. Neuropharmacol 2006;50:1016–1029.

- Bialer M, Johannessen SI, Kupferberg HJ . Progress report on new antiepileptic drugs: a summary of the Eigth Eilat Conference (EILAT VIII). Epilepsy Res 2007; 73:1–52.

- Reddy DS. Clinical pharmacokinetic interactions between antiepileptic drugs and hormonal contraceptives. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol 2010;3:183–192.

- Ben-Manachem E, Biton V, Jatuzis D Efficacy and safety of oral lacosmide as adjunctive therapy in adults with partial-onset seizures. Epilepsia 2007;481308–1317.

- Halasz P, Kalviainen R, Mazurkiewicz-Beldzinska M . Adjuntive lacosamide for partial-onset seizures: Efficacy and safety results from a randomized controlled trial. Epilepsia 2009;50:443–453.

- Chung S, Sperling MR, Biton V . Lacosamide as adjunctive therapy for partial-onset seizures: A randomized controlled trial. Epilepsia 2010;51:958–967.

- Isojarvi J, Rosenow F, Faught E, Hebert D, Doty P (2009) Efficacy of lacosamide in partial-onset seizures with and without secondary generalization: A pooled analysis of three phase II/III trials. Epilepsia. 50(suppl s10):112 (abs p515).

- Chen L, Haneef Z, Dorsch A Successful treatment of refractory simple motor status epilepticus with lacosamide and levetiracetam. Seizure: European Journal of Epilepsy 2011;20:263–5.

- Fountain NB, Krauss G, Isojarvi J, Dilley D, Doty P, Rudd GD. A multicenteropen-label trial to assess the safety and tolerability of a single intravenous loading dose of lacosamide followed by oral maintenance as adjunctive therapy in patients with partial-onset seizures. European Congress on Epileptology – 9th. Epilepsia. 2010;51(Suppl. 4):123 (abs p416).

- Albers JM, Möddel G, Dittrich R, Intravenous lacosamide-an effective add-on treatment of refractory status epilepticus. Seizures 2011 (article in press).

- Edwards HB, Cole AG Minimizing pharmacodynamic interaction of high doses of lacosamide. Acta Neurol Scand 2011;[Epub ahead of print].

- Sake J, Herbert D, Isojarvi J A pooled analysis of lacosamide clinical trial data grouped by mechanism of action of concomitant antiepileptic drugs. CNS Drugs 2010;24: 1055–1068.

- Novy J, Patsalos PN, Sander JW, Lacosamide neurotoxicity associated with concomitant use of sodium channel-blocking antiepileptic drugs: A pharmacodynamic interaction? Epilepsy Behav 2011;20:20–23.