| Abbreviations: | ||

| ABPM | = | ambulatory blood pressure monitoring |

| ACE | = | angiotensin converting enzyme |

| ARB | = | angiotensin receptor blocker |

| A-V | = | atrio-ventricular |

| BB | = | beta-blocker |

| BP | = | blood pressure |

| CHD | = | coronary heart disease |

| CKD | = | chronic kidney disease |

| CV | = | cardiovascular |

| CVD | = | cardiovascular disease |

| DBP | = | diastolic blood pressure |

| ECG | = | electrocardiogram |

| EF | = | ejection fraction |

| eGFR | = | estimated glomerular filtration rate |

| ESC | = | European Society of Cardiology |

| ESH | = | European Society of Hypertension |

| ESRD | = | end-stage renal disease |

| HBPM | = | home blood pressure measurement |

| HT | = | hypertension |

| ISH | = | isolated systolic hypertension |

| LV | = | left ventricle |

| LVH | = | left ventricle hypertrophy |

| OD | = | organ damage |

| PAD | = | peripheral artery disease |

| PWV | = | pulse wave velocity |

| RAS | = | renin-angiotensin system |

| RF | = | risk factor |

| SBP | = | systolic blood pressure |

| TIA | = | transient ischaemic attack. |

Introduction

Principles

The 2013 ESH/ESC guidelines continue to adhere to some fundamental principles that inspired the 2003 and 2007 guidelines, namely (i) to base recommendations on properly conducted studies identified from an extensive review of the literature, (ii) to consider, as the highest priority, data from randomized, controlled trials and their meta-analyses, but not to disregard the results of observational and other studies of appropriate scientific caliber, and (iii) to grade the level of scientific evidence and the strength of recommendations in order to more effectively alert physicians on recommendations that are based on the opinions of the experts rather than on evidence ( and ). When appropriately recognized, this can avoid guidelines being perceived as prescriptive and favour the performance of studies where opinion prevails and evidence is lacking.

Table I. Classes of recommendations.

Table II. Levels of evidence.

This shortened version of the ESH/ESC guidelines is for the practicing physician who often requires simplified information. However, whenever the physicians would like to know the source of the data upon which the recommendations are based, they are encouraged to consult the extensive version of the ESH/ESC guidelines where adequate references are given. These guidelines, however, do not override the individual responsibility of health professionals to make appropriate decisions in the circumstances of the individual patient.

New aspects

Because of new evidence on several diagnostic and therapeutic aspects of hypertension, the present guidelines differ from the 2007 ones in several points:

Re-emphasis on integration of blood pressure (BP), cardiovascular (CV) risk factors (RF), asymptomatic organ damage (OD) and clinical complications for total CV risk assessment.

Update of the prognostic significance of out-of-office BP (both ambulatory and home BP), white coat hypertension and masked hypertension.

Initiation of antihypertensive drug treatment only in patients with SBP or DBP values > 140 or 90 mmHg, independent of level of total CV risk.

Unified target SBP (< 140 mmHg) in both higher and lower CV risk patients.

Revised recommendations on treatment of hypertension in young people and in the elderly.

Liberal approach to initial monotherapy, without any all-ranking purpose scheme.

Revised therapeutic algorithm for achieveing target BP.

Revised attention to resistant hypertension.

Definitions and classifications

The continuous relationship between BP and CV and renal events make the distinction between normotension and hypertension difficult. In practice, however, cut-off BP values are universally used to facilitate the decision about treatment ().

Table III. Definitions and classification of office blood pressure levels (mmHg).

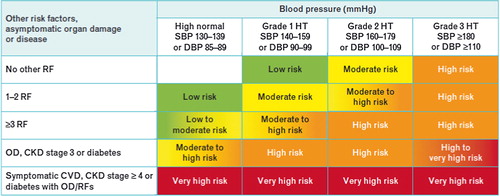

In order to help prognosis, total CV risk should be stratified in different categories (low, moderate, high and very high risk referred to the 10-year risk of CV mortality), based on BP category, CV risk factors, asymptomatic OD and presence of diabetes, and symptomatic CV disease or chronic kidney disease (CKD), as summarized in .

Figure 1. Stratification of total CV risk in categories of low, moderate, high and very high risk according to SBP and DBP and prevalence of RFs, asymptomatic OD, diabetes, CKD stage or symptomatic CVD. Subjects with a high normal office but a raised out-of-office BP (masked hypertension) have a CV risk in the hypertension range. Subjects with a high office BP but normal out-of-office BP (white-coat hypertension), particularly if there is no diabetes, OD, CVD or CKD, have lower risk than sustained hypertension for the same office BP.

Diagnostic evaluation

The initial evaluation of a patient with hypertension should (i) confirm the diagnosis of hypertension, (ii) detect causes of secondary hypertension, and (iii) asses CV risk, OD and concomitant clinical conditions. This calls for BP measurement, medical history including family history, physical examination, laboratory investigation and further diagnostic tests. Some of the investigations are needed in all patients; others only in specific patient groups.

Blood pressure measurement

Office and out-of-office BP

While conventional office BP measurement currently remains the “gold standard” for screening, diagnosis and management of hypertension, it is generally accepted that out-of-office BP provides important adjunct information.

At present, BP can no longer be estimated using a mercury manometer in many – although not all – European countries. Auscultatory or oscillometric semiautomatic sphygmomanometers are used instead, but these devices should be validated according to standardized protocols and their accuracy checked periodically. gives instructions for correct office BP measurements, and provides clinical indications for out-of-office BP measurement, both measurements at home (HBPM) or 24-hour ambulatory BP monitoring (ABPM).

Tables IV. Office blood pressure measurement.

Table V. Clinical indications for out-of-office blood pressure measurement for diagnostic purposes.

Office BP is usually higher than ambulatory and home BP and the difference increases as office BP increases. Cut-off values for the definition of hypertension by home and ambulatory BP are reported in .

Table VI. Definitions of hypertension by office and out-of-office blood pressure levels.

White-coat and masked hypertension

The term “white coat” or “isolated office” hypertension refers to a condition in which BP is elevated in the office at repeated visits and normal out of the office either on ABPM or HBPM. Conversely, BP may be normal in the office and abnormally high out of medical environment, which is termed “masked” or “isolated ambulatory” hypertension.

Cut-off values to be used are those in .

Central blood pressure

Owing to the variable superposition of incoming and reflected pressure waves along the arterial tree, aortic BP (central BP) may be different from brachial BP. Central BP can be estimated indirectly by various methods. The current guidelines consider that, despite the growing interest in these methods, more investigation is needed before recommending the routine measurement of central BP for clinical use.

Medical history

The information to be obtained at the time of the first diagnosis of hypertension is indicated in .

Table VII. Personal and family medical history.

Physical examination

Physical examination aims to establish or verify the diagnosis of hypertension, establish current BP, screen for secondary causes of hypertension and refine global CV risk. Procedures for BP measurement are indicated in tables and above. Other information to be obtained by physical examination are in .

Table VIII. Physical examination for secondary hypertension, organ damage and obesity.

Laboratory investigations

Laboratory investigations are directed at providing evidence for additional risk factors, searching for secondary hypertension and looking for OD. Investigations should proceed from the most simple to the more complicated ones, as summarized in .

Table IX. Laboratory investigations.

Searching for asymptomatic organ damage

Owing to the importance of asymptomatic OD as an intermediate stage in the continuum of CV disease, and as a determinant of overall CV disease, signs of organ involvement should be sought carefully by appropriate techniques as indicated below.

Search for asymptomatic organ damage, cardiovascular disease, and chronic kidney disease

Searching for secondary forms of hypertension

A specific, potentially reversible cause of BP elevation can be identified in a relatively small number of adult patients with hypertension. However if basal work-up leads to the suspicion of a secondary form of hypertension, the patient should be referred to a specialized centre where specific diagnostic procedures may be preferred.

Treatment approach

Recommendations of previous Guidelines revised

The 2007 ESH/ESC Guidelines, like many other scientific guidelines, recommended the use of antihypertensive drugs in patients with grade 1 hypertension even in the absence of other risk factors or OD after nonpharmacological treatment had proved unsuccessful. This recommendation also specifically included the elderly hypertensive patient. The 2007 Guidelines also suggested drug treatment of patients with diabetes, previous CVD or CKD even when their BP was in the high normal range (130–139/85-89 mmHg). Furthermore, a lower BP target was recommended for these high or very-high risk patients (< 130/80 mmHg) than in patients at low-moderate risk (< 140/90 mmHg). These recommendations were reappraised in a 2009 ESH Task Force document on the basis of an extensive critical review of the evidence. The following now summarizes the conclusions for the current Guidelines: attention should be directed to the Class of recommendation and the Level of evidence, in order to distinguish what is considered compelling and what simply prudent.

When to initiate antihypertensive drug treatment

Initiation of antihypertensive drug treatment

Blood pressure treatment targets

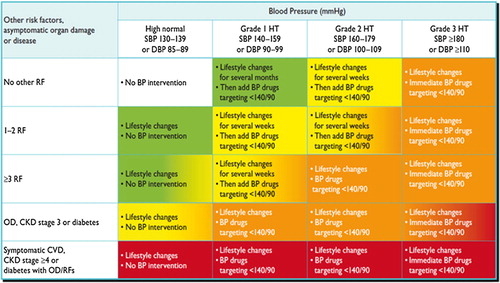

also summarizes recommendations and suggestions for treatment initiation and BP targets in the context of total risk stratification of hypertensive individuals.

Figure 2. Initiation of lifestyle changes and antihypertensive drug treatment. Targets of treatment are also indicated. Colours are as in . Consult Section 6.6 for evidence that, in patients with diabetes, the optimal DBP target is between 80 and 85 mmHg. In the high normal BP range, drug treatment should be considered in the presence of a raised out-of-office BP (masked hypertension). Consult section 4.2.4 for lack of evidence in favour of drug treatment in young individuals with isolated systolic hypertension.

Blood pressure goals in hypertensive patients

Treatment strategies

Lifestyle changes

Appropriate lifestyle changes are the cornerstone for the prevention of hypertension. They are also important for its treatment, although they should never delay the initiation of drug therapy in patients at high level of risk. Beside the BP-lowering effect, lifestyle changes contribute to the control of other CV risk factors and clinical conditions.

The lifestyle measures that have been shown to be capable of reducing BP and are therefore recommended are:

(i) salt restriction to 5–6 g/day;

(ii) moderation of alcohol consumption to no more than 20–30 g of ethanol per day in men and 10–20 g per day in women;

(iii) high consumption of vegetables and fruits and low-fat dairy products

(iv) reduction of weight to body mass index of 25 kg/m2 and waist circumference to < 102 cm in men and < 88 cm in women;

(v) at least 30 min of moderate dynamic exercise on 5 to 7 days per week

Pharmacological therapy

Choice of antihypertensive drugs

The current guidelines reconfirm that all major classes of antihypertensive agents are suitable for the initiation and maintenance of antihypertensive treatment either in monotherapy or in some combinations, and that no all-purpose ranking of drugs for general antihypertensive usage is evidence based. All classes have their advantages but also contraindications, and may be preferentially used or avoided in specific conditions. Contra-indications and preferred indications are listed in and .

Table X. Compelling and possible contra-indications to the use of antihypertensive drugs.

Table XI. Drugs to be preferred in specific conditions.

Monotherapy and combination therapy

The current Guidelines share the 2007 Guidelines opinion that monotherapy can reduce BP to target only in a limited number of patients and that most patients require the combination of at least two drugs, and they reconfirm that initiation with a drug combination can be considered in patients at high CV risk or with markedly high BP. The algorithm of , however, is a modification of the 2007 one, to emphasize that adding drugs to drugs should be done with attention to results and any compound overtly ineffective or minimally effective should be replaced, rather than retained in an automatic step-up multiple-drug approach.

Figure 3. Monotherapy vs. drug combination strategies to achieve target BP. Moving from a less intensive to a more intensive therapeutic strategy should be done whenever BP target is not achieved.

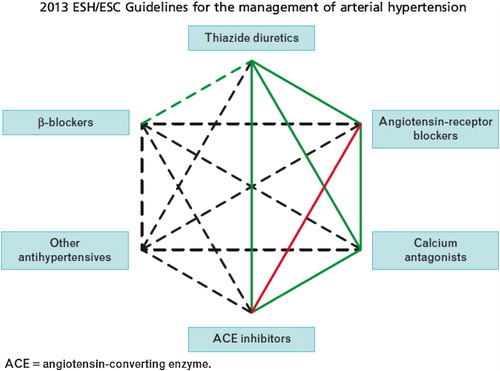

Combinations to be preferred or avoided are illustrated in .

Figure 4. Possible combinations of classes of antihypertensive drugs. Green continuous lines: preferred combinations; green dashed line: useful combination (with some limitations); black dashed lines: possible but less well tested combinations; red continuous line: not recommended combination. Although verapamil and diltiazem are sometimes used with a beta-blocker to improve ventricular rate control in permanent atrial fibrillation, only dihydropyridine calcium antagonists should normally be combined with beta-blockers.

Strengths of recommendations about choice of drugs and combinations of antihypertensive agents are given in the summary table below.

Treatment strategies and choice of drugs

Treatment strategies in special conditions

Summary recommendations for antihypertensive treatment strategies in various conditions are listed below.

White-coat and masked hypertension

Treatment strategies in white-coat and masked hypertension

Elderly

Antihypertensive treatment strategies in the elderly

Young adults

Women

Treatment strategies in hypertensive women

Diabetes mellitus

Treatment strategies in patients with diabetes

Metabolic syndrome

Treatment strategies in hypertensive patients with metabolic syndrome

Diabetic and non-diabetic nephropathy

Therapeutic strategies in hypertensive patients with nephropathy

Cerebrovascular disease

Therapeutic strategies in hypertensive patients with cerebrovascular disease

Heart disease

Therapeutic strategies in hypertensive patients with heart disease

Atherosclerosis, arteriosclerosis and peripheral artery disease

Therapeutic strategies in hypertensive patients with atherosclerosis, arteriosclerosis, and peripheral artery disease

Resistant hypertension

Therapeutic strategies in patients with resistant hypertension

Treatment of associated risk factors

Treatment of ristors associated with hypertension

Follow-up

Follow-up visits

After invitation of antihypertensive drug therapy, it is important to see the patient at 2- to 4-week intervals to evaluate the effects on BP and to assess possible side-effects. Some medications will have an effect within days or weeks but a continued delayed response may occur during the first 2 months. Once the target is reached, a visit interval of a few months is reasonable.

Elevated blood pressure at control visits

Patients and physicians have a tendency to interpret an uncontrolled BP at a given visit as due to occasional factors and thus to downplay its clinical significance. Due attention should be given to poor adherence or irregular consumption of drugs (sometimes because of adverse effects), to the white coat effect and to substances or drugs opposing the antihypertensive effect of treatment.

Can antihypertensive medication be stopped?

In some patients, in whom treatment is accompanied by an effective BP control for an extended period, it may be possible to reduce the number and dosage of drugs. This may be particularly the case if BP control is accompanied by healthy lifestyle changes. Reduction of medications should be made gradually and the patient should frequently be checked because of the risk of reappearance of hypertension.

Improvement of blood pressure control in hypertension

Despite overwhelming evidence that hypertension is a major CV risk factor and that BP lowering substantially reduce the risk, there is evidence that all over the world (i) a noticeable proportion of hypertensive individuals are unaware of this condition or, if aware, do not undergo treatment; (ii) target BP values are seldom achieved; (iii) failure to achieve BP control is associated with persistence of an elevated CV risk; and (iv) the rate of awareness of hypertension and BP control is improving slowly or not at all. As a consequence, high BP remains a leading cause of death and CV morbidity in Europe, as elsewhere in the world. Overall, three main causes of the low rate of BP control in real life have been identified: (i) physician inertia; (ii) patient low adherence to treatment, and (iii) deficiencies of healthcare systems in their approach to chronic diseases. Methods to improve adherence to physicians’ recommendations are listed in .

Table XII. Methods to improve adherence to physicians’ recommendations.

Acknowledgement

The contribution of Mrs Clara Sincich and Mrs Donatella Mihalich is gratefully acknowledged.

Appendix

ESH and ESC entities that participated in the development of the ESH/ESC Guidelines are listed in the extended version of the Guidelines (J Hypertens 2013; 31: 1281–1357).