Abstract

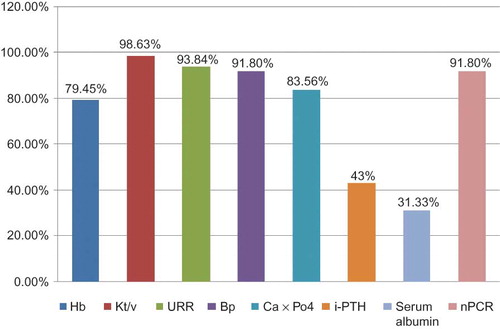

Introduction: The quality of care provided to dialysis patients is under increasing scrutiny and systematic measurements of clinical performance, relying on indicators such as levels of Kt/V, hemoglobin, and serum albumin, have been implemented. Methods: In this retrospective study we revised clinical and laboratory data of 146 chronic hemodialysis (HD) patients who met our inclusion criteria in the dialysis unit at Prince Salman Center for Kidney Diseases for a whole year – 2009. This study looked at the extent of adherence to the kidney diseases outcome quality initiative kidney diseases outcome quality initiative (K/DOQI), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidelines for prevention of transmission of infections among HD patients, and American Association of Medical Instrumentation standards for dialysis water quality. Results: A total of 146 HD patients (54.8% males and 45.2% females) were included in this study with mean age 51.21 ± 15.33 years. About 97.94% of cases had thrice-weekly sessions. An arteriovenous fistula was the vascular access in 78.1% of cases, and a permanent catheter was used in 21.9%. The mean predialysis blood pressure was ≤140/90 in 91.8% of cases. The mean hemoglobin level was 11.44 ± 1.46 g/dL in prevalent HD patients; 79.45% of cases had a hemoglobin level ≥11 g/dL. The mean serum albumin level was 33.53 ± 4.02 g/L; only 31.33% of cases had serum albumin ≥35 g/L. The mean parathormone level was 34.35 ± 28.70 pmol/L; 43.0% of patients had the target range (16.5–33 pmol/L), and the mean calcium level was 2.17 mmol/L; 89.73% of cases had the target range (2.12–2.52 mmol/L) while the mean serum phosphorus level was 1.46 mmol/L; 83.56% of patients had the target range (0.81–1.78 mmol/L). The Ca × Pi product was ≤4.5 in 83.56% of cases. The mean Kt/V value was 1.45 ± 0.18 in prevalent HD patients (98.63% and 60.96% of cases had Kt/V ≥1.2 and ≥ 1.4, respectively). All patients were negative for HIV serology test while the prevalence of hepatitis C virus-positive and hepatitis B virus-positive patients was 24.7% and 4.1%, respectively. All patients (except hepatitis B virus positive) were vaccinated against hepatitis B virus. The annual mortality rate was 5.67%. Conclusion: Our study revealed an excellent quality of care for HD patients in the field of vascular access care, hemoglobin level, blood pressure control, and dialysis adequacy. On the other hand, this study showed the need for improving the nutritional status of patients through more dietary counseling, nutritional education, and early management for nutritional problems.

INTRODUCTION

Chronic kidney disease and end-stage renal disease (ESRD) are emerging health problems that need long-term, often costly care.Citation1 While renal replacement therapy has improved many patients’ care, questions remain regarding the quality of care provided to patients by dialysis facilities. Clinical practice guidelines were established to provide recommended ranges for parameters associated with the management of ESRD patients.Citation2,3 Systematic measurements of clinical performance, relying on indicators such as levels of Kt/V, hematocrit, and serum albumin, have been implemented. These indicators have gained acceptance because they reflect the quality of relevant healthcare processes (i.e., amount of dialysis, treatment of anemia, nutrition level) and because they correlate with patient mortality and morbidity.Citation4,5 Besides, the quality of dialysis water has received special attention recently due to the large volumes of water each dialysis patient is exposed to during treatment.Citation6 The American Association of Medical Instrumentation (AAMI) had issued guidelines of dialysis water treatment and quality of product water to ensure patients’ safety.Citation6 To prevent the transmission of infections in dialysis units, Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) set out guidelines to protect against the spread of infections, especially hepatitis B and C.Citation7 Studies showed clearly that compliance with guidelines results in a better outcome.Citation8,9

We plan to accurately evaluate the current quality of care of the dialysis unit at Prince Salman Center for Kidney Diseases (PSCKD), Riyadh, KSA; assess to what extent was matched with the kidney diseases outcome quality initiative (K/DOQI) guidelines, CDC guidelines, and AAMI standards; and measure the major patient outcomes.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

This study revised clinical and laboratory data of all chronic hemodialysis (HD) patients attending the dialysis units (N = 146) who met our inclusion criteria (age ≥18 years and on regular HD for 6 months or more) at PSCKD, Riyadh, KSA, for a whole year – 2009. This study looked at the degree of adherence to the K/DOQI, CDC, and AAMI standards.

Data Collection

We collected data from the center team based on each patient’s medical and nursing records. Laboratory and clinical indices were measured by taking the mean of monthly values for annual laboratory data and monthly values for every 4 months for clinical data. Data of quality criteria were defined for individual patients in eight domains of clinical care:

1. Dialysis adequacy: The delivered dose of HD was measured by the percent of urea reduction (URR) and Kt/V value (calculated using the single pool Daugirdas II method).

2. Appropriate anemia management: Assessed by achieved levels of hemoglobin. A hemoglobin ≥11 g/dL was considered adequate.

3. Calcium and phosphate metabolism: Assessed by the calcium–phosphate product. A value of ≤ 4.5 mmol2/L2 was considered to be adequate using predialysis serum calcium and phosphorus levels.

4. Nutrition: Assessed by the serum albumin. A level >35 g/L and normalizing protein catabolic rate (nPCR) >0.8 g/kg/month were considered to be criteria of good nutrition.

5. Vascular access: Defined by the presence of a native arteriovenous fistula, a synthetic graft, or a catheter. Dialysis via a native arteriovenous fistula was considered optimal.

6. Hypertension was defined as a mean predialysis blood pressure of >140/90 mmHg over 1 week.

7. Compliance with infection control guidelines and the prevalence of hepatitis B and C infection among patients. This study also assessed the adherence to the CDC recommendations regarding hepatitis B vaccination of dialysis patients.

8. Compliance with the AAMI standards for quality of dialysis water used.

We recorded the data of all patients (demographic, laboratory, and clinical). The modified Charlson comorbidity index was calculated ().Citation10 This index was recently validated for predicting outcomes and costs in dialysis patients.Citation11 Nutritional status was scored using scored Patient-Generated Subjective Global Assessment (PG-SGA) scale.Citation12 Mortality rate for the study period was calculated using hospital records.

Table 1. Modified Charlson comorbidity index, the comorbidity points.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was done by using Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 16. Quantitative data were expressed in the form of numbers, percentages, mean, and standard deviation. Comparison between data was performed by using the chi-square test. A p-value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Demographic Data

This study included 146 chronic HD patients at PSCKD, Riyadh, KSA. There were 80 males and 66 females. The mean age was 51.21 ± 15.33 years (range 18–85 years). The mean duration of HD therapy was 6.4 years (range 1–20 years). All patients received 3–4 h of HD using volumetric machines and high-flux polysulphone membrane (1.2, 1.4, 1.6, and 1.8 m2) (Fresenius Medical Care, Saudi Advanced Renal Services Corporation Ltd., Riyadh, KSA). The dialysate flow ranged from 500 to 800 mL/min and the blood flow rate ranged from 250 to 400 mL/min. Of the patients, 97.94% had thrice-weekly dialysis sessions and 3% had twice-weekly dialysis sessions (flexibility in extending the dialysis time beyond 4 h and availability of daily dialysis if indicated). Synthetic hemodialyzers were used for a single session; dialyzer reprocessing is not practiced in the center. Bicarbonate dialysate was the base used in 100% of patients. shows the main data of the study group.

Table 2. Clinical and biochemical data of the studied group.

Vascular Access

Arteriovenous fistulae (including eight patients with arteriovenous graft (AVG)) were the vascular access in 78.1% and temporary or permanent central venous catheters (CVC) were used in 21.9% of prevalent HD cases.

Blood Pressure Control

The mean predialysis blood pressure was ≤140/90 mmHg in 91.8% of cases. The mean predialysis systolic blood pressure was 138 ± 19.82 mmHg and the mean predialysis diastolic blood pressure was 82.73 ± 17.31 mmHg.

Adequacy of HD

The mean Kt/V value was 1.45 ± 0.18 (range 0.7–2.6) in prevalent HD patients (98.63% and 60.96% of cases had Kt/V ≥1.2 and ≥ 1.4, respectively) and with regard to URR percent, the mean value was 70.45 ± 5.51% (range 47–89%); the percentage of patients who achieved ≥65% were 93.84%.

Nutritional Status

The mean serum albumin level was 33.53 ± 4.02 g/mL (range 16–46 g/mL); only 31.33% of cases had serum albumin ≥35 g/mL while the mean nPCR was 1.0 ± 0.24 g/kg/day and the percent of patients who achieved ≥0.80 was 91.80%. The mean PG-SGA score was 2.86 ± 2. 35 (range 1–11). Forty percent of patients had PG-SGA scores in the range of 0–1 (mild malnutrition to well nourished). Fifty-six percent of patients had PG-SGA scores in the range of 2–8 (mild to moderate malnourished). Four percent were severely malnourished (PG-SGA scores >9).

Anemia Management

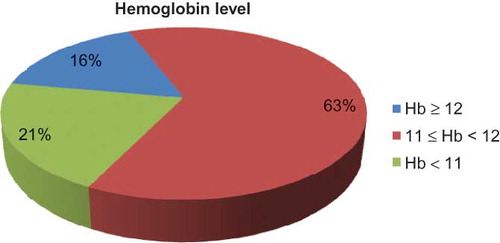

The mean hemoglobin level was 11.44 ± 1.46 g/dL in prevalent HD patients (range 5.15–15.7 g/dL). About 80% (79.45%) of cases had a hemoglobin level ≥11 g/dL and 16.43% of patients had hemoglobin level ≥12 and <13 g/dL (). The mean iron saturation was 35.25% (range 5.1–194.1 μmol/L); 98.63% of cases had iron saturation >20%, while the mean serum ferritin level was 534.22 ± 424.11 ng/mL (range 14.68–2356 ng/dL); 12.33% (18 patients) had serum ferritin level <200 ng/mL and 87.67% (128 patients) of cases had serum ferritin level >200 ng/mL; 54.8% (80 patients) had serum ferritin level from 200 to 500 ng/mL and 32.87% (48 patients) had serum ferritin level >500 ng/mL. The mean erythropoietin dose of all cases was 157.83 ± 100.62 IU/kg/week (range 9.35–567.57 IU/kg/week). Intravenous iron saccharose loading doses (10 doses; ferrosac 100 mg/dose) were given to all patients with iron saturation <20% after performing the sensitivity test and intravenous iron was not recommended if serum ferritin >500 ng/mL and contraindicated if serum ferritin >800 ng/mL.

Calcium, Phosphorus, and Parathormone

The mean intact parathormone (PTH) level was 34.35 ± 28.70 pmol/L (range 0.94–417.0); 43% of patients had the target range (16.5–33 pmol/L), 21% had mean intact PTH level <16.5 pmol/L, 33% had mean intact PTH level from 33 to 100 pmol/L, and only 3% had mean intact PTH level >100 pmol/L. The mean calcium level was 2.17 ± 0.20 mmol/dL (range 1.01–2.97 mmol/dL); 89.73% of cases had the target range (2.12–2.52 mmol/dL) and 10.27% of cases had hypocalcemia, while the mean serum phosphorus level was 1.45 ± 0.48 mmol/dL (range 0.14–3.70 mmol/dL); 83.56% of patients had the target range (0.81–1.78 mmol/dL) while 20 patients had hyperphosphatasemia (range 1.8–3.70 mmoL/dL) and only 4 patients had hypophosphatasemia. The mean Ca × Pi product was 3.15 ± 1.075 mmol2/L2. It was ≤ 4.5 mmol2/L2 in 83.56% of cases.

Adherence to Quality of Dialysis Water Standards (AAMI Standards)

Product water chemical testing, both biochemically and bacteriologically, is compliant with AAMI guidelines that advise to perform an annual biochemical analysis of product water and to perform microbial cultures monthly. Corrective measures are routinely undertaken if the colony count exceeds the allowable limit (50 CFU).Citation7 Testing for endotoxin has not yet been included in the monthly microbial testing.

Compliance with the CDC Guidelines for Infection Control in a HD Unit

Adherence to infection control guidelines is closely met in daily practice. Wearing gloves and hand washing are among the practices that are well adhered to by all nurses on all occasions. The practice of hand washing before and after patient contact is a role while nurses care for patients and touch patients’ equipment at the dialysis station. Dialysis stations (chairs, beds, tables, and machines) are disinfected and cleaned between patients. All cases are tested for hepatitis B and C infection using the hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) test and anti-HCV antibodies and PCR for HCV RNA. Follow-up testing is performed every 6 months for anti-HCV antibodies and PCR for HCV RNA for HCV-negative patients and seroconverted patients after treatment and every year for HCV-positive patients without treatment. With regard to hepatitis B, follow-up testing is performed every 3 months only for susceptible patients. Screening for anti-HBs antibody is tested every year for all vaccinated patients and all newly admitted patients. Hepatitis B vaccination is routine practice for both dialysis patients (except HBsAg-positive patients) and the healthcare personnel. A booster dose was given to all patients with low anti-HBs antibody titer <10 IU/mL. All patients were negative for HIV serology test while the prevalence of hepatitis C virus (HCV)-positive and hepatitis B virus (HBV) positive patients was 24.7% and 4.1%, respectively. HBsAg-positive patients and also HCV-infected patients were dialyzed on separate machines in an isolation room and had dedicated nurses. All negative patients for HBV and HCV were dialyzed on separate machines in separate rooms (male and female rooms).

Annual Mortality Rate

The annual mortality rate was 5.67%. Causes of death included cardiovascular events (four cases), sepsis and multiple organ failure (five cases), and sudden death (two cases). The ESRD patients who died were significantly older compared with surviving patients (p < 0.05) and had a previous history of cardiovascular disease.

Table 3. Modified Charlson comorbidity index score.

Modified Charlson Comorbidity Index Score

Our study showed that the mean modified Charlson comorbidity index was 5.71 ± 2.44 (range 2–13) . About 20% (19.9%) of patients had low score, 32% (32.2%) of patients had moderate score, 26.7% of patients had high score, and 21.2% of patients had very high score.

shows the percentage of different quality criteria achieved in the studied group.

DISCUSSION

This study was designed to evaluate the extent of compliance with the K/DOQI guidelines in the study center. A higher percentage of our patients (98.63%) were adequately dialyzed (Kt/V ≥ 1.2) compared with those reported from the Unites States (86%) and the Netherlands (59%).Citation13,14 We believe that adequacy of dialysis was very excellent in our center as nephrologists became more aware of the recommended threshold for the Kt/V. With regard to URR, it was ≥65% in 93.84% of our patients which is higher than that reported from the United States Renal Data System 2008 annual report which revealed that 91.6% of prevalent dialysis patients in 2006 achieved URR > 65%.Citation15 The main factors behind the achievement of URR ≥ 65 in our patients are a good blood flow, variable dialyzer size (1.2, 1.4, 1.6 and 1.8 m2), and flexibility in extending the dialysis time beyond 4 h and availability of daily dialysis. Concerning vascular access, our results (78.1% patients with an arteriovenous fistula) are midway between European (80%) and American (24%) results reported by the Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns survey (DOPPS).Citation16 Arteriovenous fistulae account for 80% of all vascular access in Spain, 53% of prevalent Canadian patients, and 91% of prevalent dialysis patients in Tehran.Citation17,18 This probably reflects local habits or availability of vascular surgeons dedicated to arteriovenous fistula surgery. Blood pressure seems adequately controlled in 91.8% of our patients. Moreover, cardio-protective medications such as angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin II receptor blockers, and β-blockers were given to almost our patients in our dialysis center. Regarding anemia management, intravenous iron and erythropoietin therapy were provided by the administration on regular and frequent bases due to good financial supply. Understandably, most of our nephrologists were fully aware of the hemoglobin target of 11–12 g/dL. Correction of anemia to the K/DOQI target of 11–12 g/dL was achievable in 79.45% of prevalent dialysis cases and nearly reached the target identified by the European Best Practice Guidelines (target of >11 g/dL for 85% of the population).Citation19,20 The mean value of hemoglobin (Hb) in our study (11.44 ± 1.46 g/dL) matches with that reported by the DOPPS study.Citation21 The mean Hb levels were 12 g/dL in Sweden; 11.6–11.7 g/dL in the United States, Spain, Belgium, and Canada; 11.1–11.5 g/dL in Australia/New Zealand, Germany, Italy, the United Kingdom, and France; and 10.1 g/dL in Japan.Citation21 Achieving the KDOQI target for anemia is excellent in our center because of the good governmental budget and good personal incomes. Actually about 16% of the patients had hemoglobin level above 12 g/dL mainly due to other medical conditions (Adult Poly Cystic Kidney Disease, Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease and HCV infection and may be to a less extent due to overuse of Erythropoiesis Stimulating Agent). Another area of good practice is the maintenance of calcium and phosphorus metabolism within K/DOQI targets in our dialysis patients. These data are comparable with the data reported by the DOPPS study. The main reasons for the good phosphate control in our study group are dietary compliance, dietitian service, available chances of receiving frequent or daily dialysis, and affordable non-calcium phosphate binders (sevelamer). However, mild phosphate and calcium disturbances are often asymptomatic, and aggressive use of phosphate binders and active vitamin D sterols to treat secondary hyperparathyroidism and hyperphosphatasemia is commonly complicated by the risk of hypercalcemia. Thanks to calcimimetic drugs usage (cinacalcet), the risk of hypercalcemia was no longer a problem. Eighty-three percent of our patients had normal serum calcium phosphate product (<4.5 mmol2/L2) which is within K/DOQI targets. Our study shows relatively good control of secondary hyperparathyroidism. Achievement of the PTH target within that recommended by the K/DOQI guidelines now is not difficult task for physicians due to usage of new non-calcium-based phosphate binders (sevelamer) and new calcimimetic drugs (cinacalcet). The DOPPS study had reported overall serum iPTH levels exceeding the K/DOQI target (i.e., 33 pmol/L) in 28.6% of patients (DOPPS I, 1999) and in 26.1% of patients (DOPPS II, 2002).Citation8 About 21% of the patients had relative hypoparathyroidism (iPTH ≤ 16.5 pmol/L) with high risk for adynamic bone disease which was prevalent in old age, females, and diabetics. Because of high morbidity and mortality due to musculoskeletal and cardiovascular causes, the correction of relative hypoparathyroidism should be rapidly considered. An area of weak compliance with K/DOQI guidelines is the nutritional status; hypoalbuminemia was observed in 68.64% of our patients. Although serum albumin was shown to predict mortality in dialysis patients, hypoalbuminemia might be also related to other factors, such as liver disease and inflammatory states; nephelometric method—used for albumin assay in our center—which gives lower results might also contribute in part. On the contrary, the nPCR was ≥0.80 g/kg/day in 91.80% of patients. Nevertheless, the absence of a nutritional assessment by the two methods in our patients and absence of widespread nutritional support indicate a deficiency in care. Indeed, dietitians were available in our center, which may explain the fairly high standard of nutritional care in our patients and the regular monitoring of other nutritional indicators like energy and protein intake, muscle mass, visceral protein pools, and serum bicarbonate as recommended by the K/DOQI.Citation22,23

Infection control measures were excellently achieved in our center especially in the care of hepatitis B patients. Hepatitis C antibodies were positive in 24.07% of HD patients which was considered low incidence in HD units and was correlated significantly, on the one hand, with very limited blood transfusion and, on the other hand, with wide practice of infection control measures. This study showed high comorbidity among prevalent dialysis patients according to modified Charlson comorbidity index. About 48% of patients had annual mortality rate ≥ 0.27% which was considered significantly high. Development of ESRD in middle-aged subjects usually leads to disruption of patients’ social and physical activities, with subsequent psychological distress. The lack of association between laboratory parameters and Charlson comorbidity index (apart from low serum albumin) may suggest that socioeconomic factors, and symptom burden, are the main determinants of general health perception and physical and mental capabilities in this cohort of patients.Citation24,25

The annual mortality rate was as low as 5.67%. Old age, cardiovascular disease, and sepsis were associated with high mortality in this study. Cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and old age were associated with higher mortality rates in the DOPPS study.Citation26 The relatively low mortality rate in our dialysis population can be explained by their good dialysis adequacy, good hemoglobin level, good blood pressure control, very good infection control system achievement, and the low rate of use of a CVC. Our study has several strengths and limitations. The retrospective design does not afford a prospective assessment of quality of care and may not be as effective as periodic monitoring of quality indicators at stimulating improvement projects in treatment facilities.Citation27,28 On the other hand, enrollment of every patient on dialysis in our center ensured and avoided opportunities for patient selection bias. Finally, the usefulness of evaluation of quality of care is markedly reduced if it is not followed by a continuous quality improvement program within dialysis facilities.Citation29 This would necessitate implementation of an educational program across the public and strong commitment to evidence-based guidelines and enhancing their capacity to measure quality of care and to act on observed deficiencies.Citation30

To conclude, this study revealed an excellent quality of care for HD patients in the fields of vascular access care, anemia management, dialysis adequacy, blood pressure control, infection control system, calcium and phosphate metabolism, and PTH control. It also reveals the need for improving nutritional status with dietary counseling. Better standardization and repeated evaluation of treatment goals and processes, according to recognized clinical practice guidelines, would be likely to reduce the weak area we observed and potentially improve the quality of care.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors thank the medical and nursing staff of PSCKD for their help and data collection.

Declaration of interest: The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

REFERENCES

- Modi GK, Jha V. The incidence of end-stage renal disease in India: A population-based study. Kidney Int. 2006;70:2131–2133.

- K/DOQI. Clinical practice guidelines for chronic kidney disease: Evaluation, classification and stratification. Am J Kidney Dis. 2002;39:S1–S266.

- European Best Practice guidelines Expert Group on Hemodialysis. European Renal Association Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2007;22 (Suppl. 2). Available at: http://www.ndt-educational.org/guidelines.asp. Accessed November 10, 2008.

- Lowrie EG, Huang WH, Lew NL. Death risk predictors among peritoneal dialysis and hemodialysis patients: A preliminary comparison. Am J Kidney Dis. 1995;26:220–228.

- Port FK, Ashby VB, Dhingra RK, Roys EC, Wolfe RA. Dialysis dose and body mass index are strongly associated with survival in hemodialysis patients. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2002;13:1061–1066.

- ANSI/AAMI RD52. Association for the Advancement of Medical Instrumentation: American National Standard, Dialysate for Hemodialysis. Arlington, VA: ANSI/AAMI RD52; 2004.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Recommendations for preventing transmission of infections among chronic hemodialysis patients. 2001. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtmL/rr5005a1.htm. Accessed November 10, 2008.

- Port FK, Pisoni RL, Bommer J, . Improving outcomes for dialysis patients in the international dialysis outcomes and practice patterns study. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;1:246–255.

- Locatelli F, Pisoni RL, Akizawa T, . Anemia management for hemodialysis patients: Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative (K/DOQI) guidelines and Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study (DOPPS) findings. Am J Kidney Dis. 2004;44:27–33.

- Beddhu S, Bruns FJ, Saul M, Seddon P, Zeidel ML. A simple comorbidity scale predicts clinical outcomes and costs in dialysis patients. Am J Med. 2000;108:609–613.

- Ortega T, Ortega F, Diaz-Corte C, Rebollo P, Ma Baltar J, Alvarez-Grande J. The timely construction of arteriovenous fistulae: A key to reducing morbidity and mortality and to improving cost management. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2005;20:598–603.

- Goldestein D. Assessment of nutritional status in renal diseases. In: Mitch W, Klahr S, eds. Handbook of Nutrition and the Kidney. 3rd ed., New York: Lippincott and Raven; 1998:45–86.

- 2001 Annual Report: ESRD Clinical Performance Measures Project. Am J Kidney Dis. 2002;39(5 Suppl. 3):S4–S98.

- Termorshuizen F, Korevaar JC, Dekker FW, . Time trends in initiation and dose of dialysis in end-stage renal disease patients in the Netherlands. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2003;18:552–558.

- United States Renal Data System (USRDS). 2008. Annual report. Available at: http://www.usrds.org/adr.htm. Accessed May 20, 2009.

- Pisoni RL, Young EW, Dykstra DM, . Vascular access use in Europe and the United States: Results from the DOPPS. Kidney Int. 2002;61:305–316.

- Mendelssohn D, Ethier J, Elder SJ, Saran R, Port FK, Pisoni RL. Hemodialysis vascular access problem in Canada: Results from the Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study (DOPPS II). Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2006;21:721–728.

- Mahdavi-Mazdeh M, Zamyadi M, Nafar M. Assessment of management and treatment responses in hemodialysis patients from Tehran province, Iran. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2008;23:288–293.

- European best practice guidelines for the management of anaemia in patients with chronic renal failure. Working Party for European Best Practice Guidelines for the Management of Anaemia in Patients with Chronic Renal Failure. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1999;14(Suppl. 5):1–50.

- Jacobs C, Horl WH, Macdougall IC, . European best practice guidelines 5: Target hemoglobin. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2000;15(Suppl. 4): 15–1920.

- Locatelli F, Pisoni RL, Combe CH, . Anemia in hemodialysis patients of five European countries: Association with morbidity and mortality in the Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study (DOPPS). Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2004;19:121–132.

- Aparicio M, Cano N, Chauveau P, . Nutritional status of hemodialysis patients: A French national cooperative study. French Study Group for Nutrition in Dialysis. Nephrol Dial Transplant. ;1999;(14):1679–1686

- National Kidney Foundation. NKF-K/DOQI Clinical Practice Guidelines for Nutrition of Chronic Renal Failure. New York: National Kidney Foundation; 2001:15–46.

- Ibrahim S, El Salamony O. Depression, quality of life and malnutrition-inflammation scores in hemodialysis patients. AJN. 2008;28:784–791.

- Ismail S, El Salamony O. Evaluation of depression, quality of life and malnutrition inflammation scores in hemodialysis patients: A cross sectional analysis. NDT Plus. 2008;1:59–60.

- Bradbury BD, Fissell RB, Albert JM, . Predictors of early mortality among incident US hemodialysis patients in the Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study (DOPPS). Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;2:89–99.

- Hudson M, Weisbord S, Arnold R. Prognostication in patients receiving dialysis. fast facts and concepts. 191. 2007. Available at: http://www.eperc.mcw.edu/fastfact/ff_191.htm. 2007. Accessed October 2007.

- Cabana MD, Rand CS, Powe NR, . Why don’t physicians follow clinical practice guidelines? A framework for improvement. J Am Med Assoc. 1999;282:1458–1465.

- Collins AJ, Roberts TL, St Peter WL, Chen SC, Ebben J, Constantini E. United States renal data system assessment of the impact of the national kidney foundation-dialysis outcomes quality initiative guidelines. Am J Kidney Dis. 2002;39:784–795.

- Diamond LH. Local implementation of clinical practice guidelines and continuous quality improvement: Challenges and opportunities. Semin Dial. 2000;13:364–368.