Abstract

Aim: Contrast-induced nephropathy (CIN) is a relatively common and serious complication, which occurs after the administration of contrast materials to patients. Although the pathophysiology of CIN is not exactly understood, ischemia of the medulla, oxidative stress, and direct toxicity of the contrast material are some of the factors that are implicated for the pathogenesis of CIN. To date, the only therapy that reduces the risk of CIN is volume expansion. There are conflicting results about the roles of angiotensin receptor blockers (ARB) and calcium channel blockers (CCB) in studies on CIN. For this reason the aim of this study was to compare the efficiency of the prophylactic use of amlodipine/valsartan plus hydration versus hydration only for the prevention of CIN in patients undergoing coronary angiography (CAG). Patients and methods: We prospectively enrolled 90 patients whose baseline serum creatinine levels were under 2.1 mg/dL and who were scheduled for CAG. Patients were divided into two groups. Group I (n = 45), consisted of patients who received amlodipine/valsartan plus hydration, group II (n = 45) consisted of patients who received only hydration. The patients in group I were given amlodipine/valsartan 5/160 mg once a day for a total of 3 days, starting one day before CAG and continuing on the day of and the day after the procedure. A 1 mL/kg/h sodium chloride infusion was administered for a total of 24 h, starting 12 h before the procedure and 12 h after, in all patients. The baseline serum creatinine (Scre) level was obtained before the procedure and repeated 48 h after. CIN was defined as an increase of ≥0.5 mg/dL or an increase of >25% in baseline Scre on the second day after CAG. Results: The baseline clinical characteristics of the treatment groups were similar. Baseline Scre was 1.13 ± 0.33 in group I and 1.07 ± 0.23 mg/dL in group II (p = 0.31). There was a significant difference between the Scre levels 48 h after CAG between the two groups (1.18 ± 0.33–1.05 ± 0.23) (p = 0.03). The reason for this was the increase of Scre in group I. CIN occurred in 17.8% (8/45) of patients in group I and in 6.7% (3/45) of patients in group II (p = 0.197). In the diabetic subgroup, CIN occurred in 10.5% (2/19) of patients taking amlodipine/valsartan and in none of the patients in group II (p = 0.486). The Mehran scores of the patients who developed CIN were significantly higher than those patients who did not develop CIN. Conclusion: Amlodipine/valsartan therapy plus hydration did not reduce the risk of CIN in chronic kidney disease (CKD) Stage 2 patients who underwent elective CAG using a low-osmolar nonionic contrast medium. This is because there was a decrease in the glomerular filtration rate (GFR) using the Levey Modification of Diet in Renal Disease (MDRD) formula in the amlodipine/valsartan group and CIN occurred at a higher frequency in this group; ARBs and CCBs may be withheld before CAG in high-risk patients.

INTRODUCTION

Contrast-induced nephropathy (CIN) is reported to be the third leading cause of acute renal failure in hospitalized patients.Citation1 Acute renal failure due to CIN often occurs after coronary angiography (CAG) and/or radiodiagnostic procedures because of the use of the contrast dye, and its incidence is about 11%.Citation2

CIN is usually defined by an increase in serum creatinine (Scre) by 0.5 mg/dL or by 25% from baseline within 48–72 h after contrast administration and is associated with prolonged duration of hospitalization and mortality.Citation3

Prolonged arterial vasoconstriction and direct tubular toxicity are postulated as mechanisms in the development of CIN.Citation4 There is a paucity of data regarding the use of medications and drugs for the prevention of CIN. Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEIs) and angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) counteract the effect of angiotensin II and subsequent medullary ischemia after contrast administration.Citation5 Nevertheless, they cause a decrease in GFR and can increase the risk of CIN. Calcium channel blockers (CCBs) antagonize afferent arteriole vasoconstriction and may have a renoprotective effect by this way. However, previous reports have showed conflicting results that the use of ACEIs/ARBs or CCBs either increase or decrease the risk of CIN. Therefore, we undertook a randomized prospective trial to assess the role of ARBs and CCBs on the risk of CIN.

METHODS

Patient Population

This trial was a randomized, controlled single-center study to test primarily the hypothesis that a combined therapy of hydration plus amlodipine and valsartan would be better than only hydration to prevent CIN.

We enrolled 90 eligible patients admitted for CAG and ventriculography between November 2010 and June 2011. Scre concentration of <2.1 mg/dL was the major inclusion criterion. Patients with an acute ST elevation myocardial infarction, manifest congestive heart failure (New York Heart Association class IV), hemodynamic instability (defined as systolic blood pressure (SBP) <90 mmHg on at least two consecutive measurements or patients requiring pressors), prior exposure to contrast media within 7 days, use of a nephrotoxic drug within 48 h and contraindication for amlodipine and valsartan prescription were excluded.

Study Design

One hundred and nine patients were assessed for eligibility, 5 patients refused to participate in the study and 4 patients did not meet the inclusion criteria; 10 patients were discharged from the hospital on the day after the CAG, and therefore we could not perform the second kidney function tests, so a total of 90 patients were enrolled in the study. Block randomization using random number tables was performed for eligible patients. The approval was taken for the study from the Ethics Committee and all subjects gave the written informed consent. Patients were randomly divided into two groups. Each patient received hydration therapy with isotonic sodium chloride over 12 h before and after exposure to contrast media at a rate of 1 mL/kg/h. The first group received three doses of amlodipine and valsartan 5/160 mg besides hydration therapy (AVH group): one dose was given 24 h before the procedure, the second was given on the morning before and the last dose was given 24 h after contrast media exposure. The second group received only hydration according to the above mentioned protocol (H group).

Baseline Scre was determined before contrast media administration and 48 h after the procedure. The simplified MDRD equation was used to estimate the estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR). CIN was the primary endpoint, defined as an absolute increase in Scre level of ≥0.5 mg/dL and/or an increase of ≥25% of Scre from baseline within 48 h after contrast media exposure.

CAG and percutaneous coronary interventions were performed by using arterial access from either the right or left femoral arteries according to the Judkins technique by using 6F catheters. Left ventricular function was evaluated in all patients by using a Vingmed System 7 echocardiography machine and a 2.5 MHz probe (GE Vingmed Ultrasound, Horten, Norway) before the procedure. Left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) was measured by two-dimensional echocardiography via the modified Simpson method.Citation6 Iopromide, a low-osmolar, nonionic contrast agent (Ultravist 370™, Schering AG, Berlin, Germany) was used in all procedures. We also estimated the Mehran risk scoreCitation7 in prediction of CIN in all patients before the procedure. Anemia was defined as baseline hematocrit value <39% for men and <36% for women according to Mehran risk stratification. Prespecified clinical and laboratory demographic information was obtained from hospital charts.

The spot urine microprotein-to-creatinine ratio (mg/mg) was calculated.

Statistical Analyses

Continuous variables with normal distribution are expressed as mean ± SD. Median value is used where normal distribution is absent. Categorical variables are given as percent. Comparisons of continuous variables between groups were assessed by using the Student’s t-test for normally distributed data and the Mann-Whitney U test for non-normally distributed data. In within-subject comparisons of continuous variables, that is before and after CAG, the paired t-test was used. p-Value <0.05 was considered for statistical significance. All statistical analyses were performed with SPSS 15.0 for Windows.

RESULTS

The baseline biochemical and clinical characteristics of the patients are listed in . There was no statistically significant difference between the two groups in terms of age, sex, body mass index (BMI), LVEF, baseline Scre, eGFR, the volume of the contrast agent, the percentage of patients with hypertension (HT), diabetes mellitus (DM), diuretic use, smoking, LDL-C, total cholesterol, hemoglobin, and the Mehran risk score. Baseline proteinuria and multivessel involvement were significantly higher in AVH group than in H group.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of patients.

shows post-angiographic changes in renal parameters and CIN incidence in the study groups. Although the baseline Scre levels did not differ between the groups, after 48 h, there was a significant difference between the groups. The Scre of the AVH group increased and was higher than the H group within 48 h (p = 0.03). The range of the patients’ eGFR was 32.97–136.58 mL/min and the mean eGFR was 70.60 ± 27.37 mL/min in the overall patient group. Despite the fall in the eGFR levels at 48 h after CAG in the AVH group, it did not differ significantly between the two groups 48 h after the procedure.

Table 2. Post-angiographic changes in renal parameters and CIN incidence in the two groups.

Although there was a significant difference for the baseline proteinuria between the groups, the difference disappeared within 48 h according to the fall in proteinuria in the AVH group. The systolic and diastolic blood pressures of the treatment groups did not change significantly before and after the CAG.

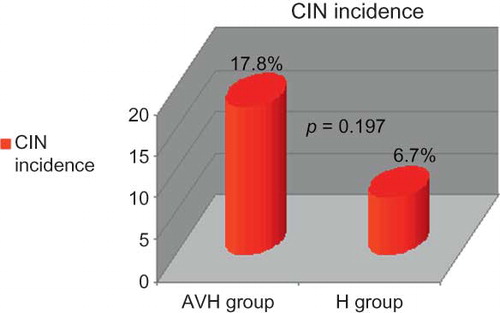

The primary endpoint as incidence of CIN occurred in 12.2% (11 of 90) of the overall study population, 17.8% (8 of 45) in the AVH group, and 6.7% (3 of 45) in the H group (p = 0.197) (). The CIN incidence was not statistically significant between the two groups. None of the patients who developed CIN needed dialysis. Two of the 8 patients who developed CIN in the AVH group were diabetic, but none of the 3 patients in the H group who developed CIN was diabetic.

Among the patients with eGFR <60 mL/min (n = 32), CIN developed in 2 of 19 patients in the AVH group, and none of the patients in the H group (n = 13).

Despite the similarity between the Mehran risk scores of the two groups before the procedure (7–6), the Mehran risk scores of the patients in whom CIN developed was significantly higher than the patients who did not develop CIN (11–6) (p = 0.046). Also, the hemoglobin values of the patients who developed CIN were significantly lower than those patients who did not develop CIN (12.7 ± 2.5–14.01 ± 2.14) (p = 0.046) (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

CIN is a serious complication of the use of contrast dye. Acute kidney injury due to contrast medium use can be a reversible process or terminate in permanent dialysis. Therefore, it is important to determine the risk of patients before CAG in order to protect the kidneys. Age >75 years, congestive heart failure, DM, contrast volume (>100 mL), and chronic kidney disease are the major risk factors of CIN as stated by Mehran and colleagues.Citation7 In our study, the baseline GFR was 70.60 ± 27.37 mL/min, and diabetic patients were 39.2% of the study population. The mean age of the patients was 64.22 ± 10.79 years. We measured Scre levels 48 h after the procedure and no further Scre measurements were obtained. The CIN incidence was 12.2% and although the rise in Scre occurs within the first 24 h after exposure to contrast media in 80% of the patients, the absence of data later than 48 h after CAG in the present study might be the reason for the low incidence of CIN.Citation8

When the baseline GFR, the percentage of diabetic patients, and the mean age of our study group were considered together, the risk stage of our group was moderate according to Mehran risk stratification of CIN, and the expected risk of CIN was 14% and dialysis necessity was 0.12%. Increasing Mehran score number confers exponentially increased CIN risk. In our study group, CIN incidence was 12.2% and there was no need for dialysis. Therefore, our results were consistent with the risk prediction of Mehran.

In the present study, the Mehran risk scores of the patients who developed CIN were significantly higher than those of the patients who did not and this finding confirms that Mehran risk stratification is a reliable method.

According to the previous studies comparing dihydropyridines and ACE inhibitors in diabetic nephropathy, dihydropyridines were as effective as ACE inhibitors for the prevention of diabetic nephropathy.Citation9–11 We believe that the combination of a dihydropyridine-type calcium channel blocker and an ARB might be more effective than their individual use for the prevention of CIN. We therefore performed this prospective, randomized trial to evaluate their combined effect on the incidence of CIN.

We used valsartan as the ARB to prevent CIN, because ARBs show a vasodilatory effect on the efferent arteriole and abolish medullary ischemia by inhibiting the effect of angiotensin II. Nevertheless, it is known that they cause a decrease in GFR and an increase in Scre. There are conflicting results about the issue of angiotensin inhibition in CIN in randomized trials. A study by Gupta et al.Citation5 found a 79% risk reduction in CIN in the group receiving captopril therapy. In contrast, Toprak et al.Citation12 found a statistically significant increase in CIN in the group treated with captopril therapy. In our study the patient population was similar to the latter study. Likewise, we found that the CIN rates were higher in the AVH group than the H group (17.8% vs. 6.7%), although the difference was not significant (p = 0.197). In our study, the range of the eGFR was 32.97–136.58 and the mean eGFR was 70.60 ± 27.37 and among patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) stage 1–3, the use of an ARB and CCB combination did not significantly change the rate of CIN when compared with patients not using them.

Although in the present study, the percentage of the diabetic patients was 42.2% (n = 19) in the AVH group, only 2 of them (10.5%) developed CIN, and none of the diabetic patients in the hydration only group developed CIN and the difference was not significant. These data are consistent with the study of Toprak et al.,Citation12 because in that study among the patients who developed CIN there were no diabetic patients. The low incidence of CIN in diabetic patients in these studies may be due to the multiple factors that take part in the pathogenesis of CIN.

In the present study, among patients with CKD (GFR <60 mL/min), the 2 patients who developed CIN were in the AVH group, and no patients in the hydration only group developed CIN (p = 0.502), most of the patients that developed CIN had a GFR of >60 mL/min. In a study by Dangas et al.Citation13 it was shown that preprocedural ACE inhibitor treatment was associated with a lower risk of CIN only in patients with GFR <60 mL/min. Our results seem comparable with this study in that the patient population of our study consisted of mainly GFR >60 mL/min patients and valsartan and amlodipine treatment resulted in a higher incidence of CIN in this group.

The incidence of CIN is over 10% in the elderly.Citation14 The reasons why elderly patients are at a high risk of developing CIN is multifactorial: age-related decrease in GFR, the presence of renovascular disease, and the use of a greater amount of contrast due to more difficult vascular access.Citation15 In their study, Cirit M et al.Citation16 found that the use of ACE inhibitor therapy before CAG increases the incidence of CIN in the elderly. Consistent with that study, the mean age of our study group was 64.22, and although the difference between groups was not significant, the patients in the amlodipine/valsartan pretreatment group were older (66.38–62.07) and CIN incidence was higher in this group.

Older age and the high percentage of hypertension (66.7%) in our patients raise the possibility of multivessel coronary involvement as a risk predictor of CIN in the present study. Indeed, the percentage of ≥2 coronary vessel involvement was 25.6% in our study, it was 33.4% in the AVH group and 17.8% in the H group (p = 0.009). The higher incidence of multivessel disease in the AVH group might be the reason for the higher incidence of CIN in this group.

CCBs are believed to have a renoprotective effect via antagonizing afferent arteriole vasoconstriction. Previous experimental studies showed that intravenous or intra-arterial infusions of verapamil and diltiazem for the prevention of CIN decreased the duration and degree of renal vasoconstriction.Citation17 We used amlodipine as the calcium antagonist to prevent CIN, since it has a sustained smooth vasodilatory effect compared to other short-acting dihydropyridines.Citation4 In previous studies, the available data on the use of CCBs for the prevention of CIN is conflicting and not clarified yet.

In a study by Arici et al.,Citation4 it was shown that pretreatment with a long-acting dihydropyridine calcium antagonist (amlodipine) affected neither urinary enzyme excretion nor the alteration observed in Scre the day after CAG. In contrast, Spangberg et al.Citation18 found no difference between the felodipine and placebo groups in the percentage decrease of GFR, and because the baseline GFR was lower in the felodipine group it was attributed to the protective effect of felodipine.

In our study, amlodipine pretreatment in combination with an ARB did not prevent the increase observed in 48th h Scre levels following CAG (although it did not reach statistical significance).

A recent study demonstrated that a lower baseline hematocrit was an independent predictor of CIN and each 3% decrease in baseline hematocrit resulted in a significant increase in the odds of CIN in patients with and without chronic kidney disease.Citation19 The findings of the present study support these data. In our study, 4 of the 11 patients who developed CIN were anemic and the hemoglobin values of the patients who developed CIN were significantly lower than the others.

Among the patients who developed CIN (n = 11), 6 of them were more than 70 years old, and 4 of them had an ejection fraction (EF) <40%. Our study indicated that, because of the heterogeneous character of CIN pathogenesis and the multifactorial nature of the disease, patients must be individually evaluated before CAG and risk assessment must be performed before contrast use.

This study has several limitations: (a) We did not use creatinine clearance values based on 24 h urine collection during a true baseline clinical condition, and our eGFR calculation was subject to limitations due to the MDRD formula used; (b) We used only Scre for estimating renal function, and new biomarkers like cystatin C and N-acetyl-glucosaminidase might provide a more sensitive estimate of renal function; and (c) The number of patients was not enough to reach a statistical difference between the therapy groups.

In conclusion, amlodipine plus valsartan added to hydration did not prevent CIN in our patients. Although in the beginning of the study, the Scre and eGFR of the patients who developed CIN were better than those in the patients who did not, CIN was more visible in the AVH group, and this was linked to the multifactorial pathogenesis of CIN.

Because the pathogenesis of CIN is heterogeneous, further studies are needed to clarify the causal role of CCB and ARB combination in prevention of CIN, and to decide whether to withhold ARB and CCB combination before CAG

Declaration of interest: The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

REFERENCES

- Hou SH, Bushinsky DA, Wish JB, Cohen JJ, Harrington JT. Hospital-acquired renal insufficiency: a prospective study. Am J Med. 1983;74(2):243–248.

- Nash K, Hafeez A, Hou S. Hospital-acquired renal insufficiency. Am J Kidney Dis. 2002;39(5):930–936.

- Rihal CS, Textor SC, Grill DE, . Incidence and prognostic importance of acute renal failure after percutaneous coronary intervention. Circulation. 2002;105(19): 2259–2264.

- Arici M, Usalan C, Altun B, . Radiocontrast-induced nephrotoxicity and urinary alpha-glutathione S-transferase levels: effect of amlodipine administration. Int Urol Nephrol. 2003;35:255–261.

- Gupta RK, Kapoor A, Tewari S, Sinha N, Sharma RK. Captopril for prevention of contrast-induced nephropathy in diabetic patients: a randomised study. Indian Heart J. 1999;51:521–526.

- Simpson DH, Chin CT, Burns PN. Pulse inversion Doppler: a new method for detecting nonlinear echoes from microbubble contrast agents. IEEE Trans Ultrason Ferroelectr Freq Control. 1999;46(2):372–382.

- Mehran R, Aymong ED, Nikolsky E, . A simple risk score for prediction of contrast-induced nephropathy after percutaneous coronary intervention: development and initial validation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;44:1393–1399.

- Rosenstock JL, Bruno R, Kim JK, . The effect of withdrawal of ACE inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers prior to coronary angiography on the incidence of contrast-induced nephropathy. Int Urol Nephrol. 2008;40:749–755.

- Rossing P, Tarnow L, Boelskifte S, Jensen BR, Nielsen FS, Parving HH. Differences between nisoldipine and lisinopril on glomerular filtration rates and albuminuria in hypertensive IDDM patients with diabetic nephropathy during the first year of treatment. Diabetes. 1997;46:481–487.

- Velussi M, Brocco E, Frigato F. Effects of cilazapril and amlodipine on kidney function in hypertensive NIDDM patients. Diabetes. 1996;45:216–222.

- Zucchelli P, Zuccala A, Borghi M. Long-term comparison between captopril and nifedipine in the progression of renal insufficiency. Kidney Int. 1992;42:452–458.

- Toprak O, Cirit M, Bayata S, Yeşil M, Aslan SL. The effect of pre-procedural captopril on contrast-induced nephropathy in patients who underwent coronary angiography. Anadolu Kardiyol Derg. 2003;3:98–103.

- Dangas G, Iakovou I, Nikolsky E, . Contrast-induced nephropathy after percutaneous coronary interventions in relation to chronic kidney disease and hemodynamic variables. Am J Cardiol. 2005;95:13–19.

- Rich MW, Crecelius CA. Incidence, risk factors, and clinical course of acute renal insufficiency after cardiac catheterization in patients 70 years of age or older. A prospective study. Arch Intern Med. 1990;150:1237–1242.

- Kohli HS, Bhaskaran MC, Muthukumar T, . Treatment related acute renal failure in the elderly: a hospital-based prospective study. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2000;15:212–217.

- Cirit M, Toprak O, Yesil M, . Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors as a risk factor for contrast-induced nephropathy. Nephron Clin Pract. 2006;104:20–27.

- Bakris GL, Burnett JC Jr. A role for calcium in radiocontrast-induced reductions in renal hemodynamics. Kidney Int. 1985;27:465–468.

- Spångberg-Viklund B, Berglund J, Nikonoff T, Nyberg P, Skau T, Larsson R. Does prophylactic treatment with felodipine, a calcium antagonist, prevent low-osmolar contrast-induced renal dysfunction in hydrated diabetic and nondiabetic patients with normal or moderately reduced renal function? Scand J Urol Nephrol. 1996;30:63–68.

- Nikolsky E, Mehran R, Lasic Z, . Low hematocrit predicts contrast-induced nephropathy after percutaneous coronary interventions. Kidney Int. 2005;67(2):706–713.