Abstract:

Introduction: We described the previously unrecognized syndrome of rapid-onset end-stage renal disease (SORO-ESRD) in 2010, in the journal Renal Failure, as distinct from the classic CKD-ESRD progression of a methodical, linear, time-dependent and predictable progression from CKD through CKD stages I–V, ending in ESRD requiring renal replacement therapy (RRT). It remains unclear to what extent this syndrome may have been identified in the past without acknowledging its uniqueness. Methods: We reviewed AKI reports and ascertained cases of SORO-ESRD as defined by patients with a priori stable kidney function who subsequently exhibited unanticipated and irreversible ESRD requiring RRT following new AKI episodes. Results: Fifteen AKI reports demonstrating SORO-ESRD were analyzed. The reports span most regions of the world. The 15 studies with 20 to 1095 AKI patients each, mean age 39–65 years, published between 1975 and 2010, demonstrated SORO-ESRD rates from 1% to 85% of the AKI series. AKI was caused by hypovolemia/hypotension, infections/sepsis and exposure to nephrotoxics especially radiocontrast, NSAIDs, aminoglycosides and RAAS blocking agents, ACEIs and ARBs. Discussion: Irreversible ESRD following AKI, consistent with our recent description of a new and unrecognized syndrome has been sporadically reported in the AKI literature, without a clear mandate as a syndrome, potentially distinct from the classic ESRD. The contribution of SORO-ESRD to the global ESRD pandemic, the impact of SORO-ESRD on AV-Fistula planning, any differential behavior of SORO-ESRD versus classic ESRD in terms of mortality outcomes and any predisposing factors to SORO-ESRD as advanced age and nephrotoxic exposure all call for serious research study.

Introduction

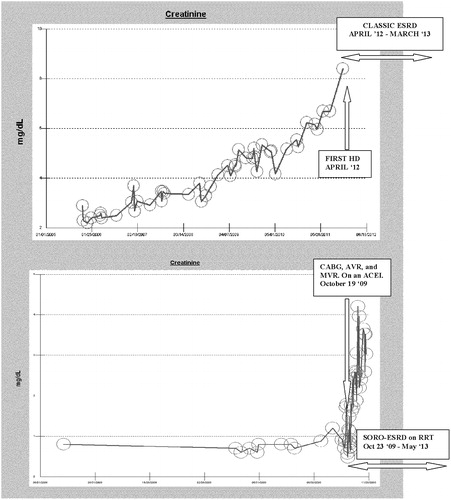

According to most nephrologists, the classic view of chronic kidney disease to end-stage renal disease (CKD-ESRD) progression is the consensus opinion of a predictable, orderly, methodical, linear, progressive, relentless and time-dependent decline in renal function, with progressively increasing serum creatinine, leading through CKD stages I, II, III, IV and V, and ultimately and inexorably ending up in ESRD and the need for renal replacement therapy (RRT)Citation1–5 (). Conversely, in opposition, the syndrome of rapid onset end-stage renal disease (SORO-ESRD), which we first described in 2010, is the sudden, unanticipated, precipitate and yet irreversible ESRD rapidly following AKI superimposed in a CKD patient with an a priori otherwise stable CKDCitation6–12 (Figure 1). SORO-ESRD is the unpredictable, nonlinear, abrupt and rapid progression to irreversible ESRD, often over a period of less than 2–4 weeks, following AKI in CKD patients with prior stable and non-progressive albeit often reduced levels of eGFRCitation6–12 (Figure 1). It remains unclear to what extent this syndrome may have been identified in the past in the medical-nephrology literature without acknowledging the uniqueness of this form of presentation of rapid onset albeit irreversible ESRD.Citation6–12 Our working diagnosis of SORO-ESRD is any CKD patient with an otherwise a priori stable eGFR of ≥30 mL/min/1.73 sq m BSA, on or before the 90th day preceding the first RRT, and which patient has remained permanently on RRT for >90 d.Citation6–12 Clearly, from the foregoing, the diagnosis of SORO-ESRD can only be made retroactively, at least 90 d after the first RRT treatment session was instituted. We investigated the incidence of SORO-ESRD as could be deduced from prior publications in the AKI literature, between 1975 and 2010, using this working definition of SORO-ESRD.Citation6–12

Methods

We reviewed AKI reports, in the English medical literature, between 1975 and 2010, analyzing patient-level data of serum creatinine trajectories and changes where possible from the available published information to ascertain the occurrence of the phenomenon of SORO-ESRD as defined by our working definition.Citation6–12

Results

Between 1975 and 2010, out of over 100 publications on AKI in the literature reviewed, we were able to identify 15 studies with enough individual patient-level data to enable the diagnosis of SORO-ESRD to be convincingly and accurately made. The AKI reports demonstrating SORO-ESRD appear in .Citation13–27 The AKI reports span most regions of the world.Citation13–27 The 15 studies incorporated patient series ranging from 20 to 1095 AKI patients each, mean age 39–65 years, and the rates of SORO-ESRD revealed from our analysis in the 15 independent reports demonstrated SORO-ESRD rates from 1% in some series, up to 85% of the AKI series.Citation13–27 AKI was commonly precipitated by hypovolemia/hypotension, infections/sepsis and exposure to nephrotoxics especially radiocontrast, NSAIDs, aminoglycosides and RAAS blocking agents, ACEIs and ARBs.Citation13–27

Table 1. Results of Literature Review of AKI reports, 1975–2010, demonstrating SORO-ESRD.

Discussion

Patients presenting with features consistent with the syndrome of rapid onset end stage renal disease, SORO-ESRD, a new unrecognized syndrome that we first described in the journal Renal Failure, in 2010, as a syndrome distinct from the classic ESRD presentation, have been similarly described in the past but were not clearly so designated as a distinct syndrome of CKD-ESRD progression.Citation6–12

Bhandari and Turney, reporting from the United Kingdom, in 1996, referred to them as “survivors of acute renal failure who do not recover renal function”.Citation17 This report constituted the largest AKI series that we examined and consisted of 1095 patients, mean age 64 years and of whom 107 (16%) developed SORO-ESRD.Citation17 These authors reviewed a consecutive series of 1095 patients with severe dialysis-dependent acute renal failure to determine the frequency of acute renal failure-induced ESRD and their subsequent course on regular dialysis therapy.Citation17 Indeed, at the time, during the entire period of this study, survivors of acute renal failure who did not regain renal function comprised 18.4% of all new patients taken on to the long-term dialysis program at The General Infirmary at Leeds, Leeds, United Kingdom.Citation17 Furthermore, Bhandari and Turney had demonstrated a worse 5-year survival among these 107 patients with SORO-ESRD, when compared to those with non-diabetic (classic) ESRD – survival rates of 40.7% versus 60.9%, respectively.Citation17 Similarly, Merino et al. in 1975, described irreversible ESRD post-operatively in older CKD patients following AKI resulting from intra-operative hypotension, with or without septicemia.Citation13 Merino et al., reporting from the University of Minnesota Hospital, MN, USA, described post-operative chronic renal failure in 125 patients with acute tubular necrosis, of which 87 died, 34 regained clinical normal function, and 4 (9.5%) survivors were left with severe permanent renal failure, two of whom required chronic dialysis and transplantation.Citation13 They dubbed the observation of permanent ESRD following on AKI as “irreversible acute renal failure”.Citation13

In June 2011, we completed a retrospective patient-level data analysis of the serum creatinine trajectories of the last 100 incident ESRD patients who had remained on maintenance hemodialysis for >90 d.Citation9–12 SORO-ESRD was diagnosed as defined above. Excluding nine patients with incomplete data, 91 patients, 57 males and 34 females, age 39–93 years were analyzed.Citation9–12 Thirty-one of 91 (34%) ESRD patients had SORO-ESRD. The 31 patients, 18 males and 13 females, had a mean age of 72 (50–92) years.Citation9–12 Our SORO-ESRD rate of 34% compares favorably with the 18.4% rate reported in 1996 by Bhandari and Turner at the Leeds General Infirmary, in the United Kingdom.Citation9–12,Citation1 In our 2011 Mayo Clinic Dialysis study, AKI immediately precipitating SORO-ESRD in the 31 patients was caused by pneumonia (8), acute decompensating heart failure (ADHF) (7), pyelonephritis (4), post-operative (5), general sepsis (3), contrast nephropathy (CN) (2) and others (2).Citation9–12 The interval between AKI and initiation of RRT was less than one week in the patients where the AKI followed cardiac surgery.Citation9–12 Quite significantly, similar to our previous reports, seven of the 31 (22%) SORO-ESRD patients experienced the precipitating AKI event while concurrently on angiotensin blockade – ACE inhibitor in four patients, ARB in two patients and spironolactone in one patient.Citation9–12 Again, here, it must be acknowledged that, similar to the experiences of Bhandari and Turney, and Merino et al., respectively, the progression to ESRD following the AKI trigger event, was unmistakably a continuum of AKI precipitating rapid CKD progression to acute but irreversible renal failure.Citation6–12,Citation13,Citation17 Merino et al. suggested that advanced age was a predisposing factor to the phenomenon which at the time they had referred to as “irreversible acute renal failure”.Citation13

In conclusion, from the foregoing, even though we were the first to describe the SORO-ESRD in 2010, the AKI literature had in the previous two decades sporadically reported on this very mesmerizing phenomenon that calls for more research. The contribution of SORO-ESRD to the current global epidemic deserves more attention than it is getting. This author and some nephrologists from around the world formed a SORO-ESRD Worldwide Consortium in April 2011 at the World Congress of Nephrology (WCN), Vancouver, Canada, to study this syndrome on a global scale. We earnestly await the results of this global study of SORO-ESRD. Furthermore, the implications of SORO-ESRD on planning for ESRD care, mortality outcomes when compared to those presenting with the classic progression to ESRD, the varying impacts on AV-Fistula First Programs and other management implications of ESRD care, brought about by this phenomenon remain unclear and call for serious research study. The potential predisposing factors for SORO-ESRD, the role of advanced age,Citation13 the role of nephrotoxic exposure including a possible role by angiotensin blockade,Citation6–12,Citation22,Citation26 all warrant further scrutiny and study. Finally, at the minimum, physicians and nephrologists alike must acknowledge the potential propensity of AKI events to terminate in irreversible ESRD, under certain conditions.Citation6–27 As a result, there is a paramount need to apply more research and practice resources to our understanding AKI, its sequel, and most importantly the overriding need to carry out new innovative research into ways and means of preventing AKI in CKD patients, in general, a theme that we have dubbed renoprevention, and which we have repeatedly espoused in several recent publications.Citation6–12,Citation28–31

Declaration of interest

No conflicts of interest declared.

Acknowledgments

This work is indeed dedicated to the memory of a very dear friend, Ikechukwu Ojoko (Idejuogwugwu), who passed away back home in Port Harcourt, Nigeria, some years ago, after a reported brief illness. Idejuogwugwu, you are truly missed.

References

- The GISEN Group. Randomized placebo-controlled trial of effect of ramipril on decline in glomerular filtration rate and risk of terminal renal failure in proteinuric, non-diabetic nephropathy. The GISEN Group (Gruppo Italiano di Studi Epidemiologici in Nefrologia). Lancet. 1997;349(9069):1857–1863

- O'Hare AM, Choi AI, Bertenthal D, et al. Age affects outcomes in chronic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;18(10):2758–2765

- Chiu YL, Chien KL, Lin SL, Chen YM, Tsai TJ, Wu KD. Outcomes of stage 3–5 chronic kidney disease before end-stage renal disease at a single center in Taiwan. Nephron Clin Pract. 2008;109(3):c109–c118

- Yoshida T, Takei T, Shirota S, et al. Risk factors for progression in patients with early-stage chronic kidney disease in the Japanese population. Intern Med. 2008;47(21):1859–1864

- Conway B, Webster A, Ramsay G, et al. Predicting mortality and uptake of renal replacement therapy in patients with stage 4 chronic kidney disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2009;24(6):1930–1937

- Onuigbo MA. Syndrome of rapid-onset end-stage renal disease: a new unrecognized pattern of CKD progression to ESRD. Ren Fail. 2010;32(8):954–958

- Onuigbo MAC, Onuigbo N. Syndrome of rapid onset end-stage renal disease revisited – observations from two chronic kidney disease populations in two continents. US Nephrology. 2010;5(2):81–85

- Onuigbo MA. Syndrome of rapid onset end-stage renal disease (SORO-ESRD): a new unrecognized pattern of CKD progression to ESRD. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;21:614A (Abstract)

- Onuigbo M, Onuigbo N. Syndrome of rapid onset end-stage renal disease (SORO-ESRD): a new unrecognized pattern of progression of CKD to ESRD. The International Society of Nephrology (ISN). World Congress of Nephrology 2011, Vancouver, Canada (Abstract)

- Onuigbo MA. Evidence of the syndrome of rapid onset end-stage renal disease (SORO-ESRD) in the acute kidney injury (AKI) literature – preventable causes of AKI and SORO-ESRD A call for re-engineering of nephrology practice paradigms. Ren Fail. 2013;35:6

- Onuigbo MA, Onuigbo N. Chronic Kidney Disease and RAAS Blockade: a New View of Renoprotection. London, England: Lambert Academic Publishing GmbH 11 & Co. KG; 2011

- Onuigbo MA, Onuigbo NT. The Syndrome of Rapid Onset End-Stage Renal Disease (SOROESRD) a new mayo clinic dialysis services experience, January 2010–February 2011. In: Di Iorio B, Heidland A, Onuigbo M, Ronco C, eds. Hemodialysis: When, How, Why. New York, NY: Nova Publishers; 2012:443--485

- Merino GE, Buselmeier TJ, Kjellstrand CM. Postoperative chronic renal failure: a new syndrome? Ann Surg. 1975;182(1):37–44

- Kjellstrand CM, Ebben J, Davin T. Time of death, recovery of renal function, development of chronic renal failure and need for chronic hemodialysis in patients with acute tubular necrosis. Trans Am Soc Artif Intern Organs. 1981;27:45–50

- Bonomini V, Stefoni S, Vangelista A. Long-term patient and renal prognosis in acute renal failure. Nephron. 1984;36(3):169–172

- Lámeire N, Matthys E, Vanholder R, et al. Causes and prognosis of acute renal failure in elderly patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1987;2(5):316–322

- Bhandari S, Turney JH. Survivors of acute renal failure who do not recover renal function. QJM. 1996;89(6):415–421

- Robertson S, Newbigging K, Isles CG, Brammah A, Allan A, Norrie J. High incidence of renal failure requiring short-term dialysis: a prospective observational study. QJM. 2002;95(9):585–590

- Al-Homrany M. Epidemiology of acute renal failure in hospitalized patients: experience from southern Saudi Arabia. East Mediterr Health J. 2003;9(5–6):1061–1067

- Yehia M, Collins JF, Beca J. Acute renal failure in patients with pre-existing renal dysfunction following coronary artery bypass grafting. Nephrology (Carlton). 2005;10(6):541–543

- Bahar I, Akgul A, Ozatik MA, et al. Acute renal failure following open heart surgery: risk factors and prognosis. Perfusion. 2005;20(6):317–322

- Bagshaw SM, Laupland KB, Doig CJ, et al. Prognosis for long-term survival and renal recovery in critically ill patients with severe acute renal failure: a population-based study. Crit Care. 2005;9:R700–R709 [PMCID: PMC1414056]; [PubMed: 16280066]

- Jayakumar M, Prabahar MR, Fernando EM, et al. Epidemiologic trend changes in acute renal failure – a tertiary center experience from South India. Ren Fail. 2006;28(5):405–410

- Kaballo BG, Khogali MS, Khalifa EH, Khaiii EA, Ei-Hassan AM, Abu-Aisha H. Patterns of “severe acute renal failure” in a referral center in Sudan: excluding intensive care and major surgery patients. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl. 2007;18(2):220–225

- Ozturk S, Arpaci D, Yazici H, et al. Outcomes of acute renal failure patients requiring intermittent hemodialysis. Ren Fail. 2007;29(8):991–996

- Al-Azzam SI, Al-Husein BA, Abu-Dahoud EY, Dawoud TH, Al-Momany EM. Etiologies of acute renal failure in a sample of hospitalized Jordanian patients. Ren Fail. 2008;30(4):373–376

- Kelly KJ, Dominguez JH. Rapid progression of diabetic nephropathy is linked to inflammation and episodes of acute renal failure. Am J Nephrol. 2010;32(5):469–475. Epub 2010 Oct 19

- Onuigbo MAC. An analytical review of the evidence-base for reno-protection from the large RAAS blockade trials after ONTARGET. Re-visitation of the potential for iatrogenic renal failure with RAAS blockade? A call for caution. Nephron Clin Pract. 2009;113(2):c63–c69. Epub 2009 Jul 14

- Onuigbo MAC. Reno-prevention vs. reno-protection: a critical re-appraisal of the evidence-base from the large RAAS blockade trials after ONTARGET – a call for more circumspection. QJM. 2009;102:155–167. Epub 2009 Jan 5

- Onuigbo MA. Renoprevention: a new concept for reengineering nephrology care-an economic impact and patient outcome analysis of two hypothetical patient management paradigms in the CCU. Ren Fail. 2013;35(1):23--28

- Onuigbo MA. Exposure to inhibitors of the reninangiotensin system is a major independent risk factor for acute renal failure induced by sucrose containing intravenous immunoglobulins. A case-control study. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2012;21(3):320--2