Abstract

Background: The prevalence of chronic kidney disease (CKD) and end-stage renal disease (ESRD) has increased worldwide; however, data regarding the prevalence of CKD in Jordan are limited. Therefore, the present study investigated the associated risk factors of both CKD and ESRD in Jordanian patients. Methods: A convenience sample of 161 patients with CKD (n = 92) and ESRD (n = 69) was recruited through randomly selected hospitals from the governmental, private and educational sectors in Jordan. A sociodemographic data and behavioral variables (exercise frequency per week, body mass index, and smoking status) were collected and compared between the two groups to obtain the needed information. Results: ESRD in amounted to relatively 68% in males and 52% in the unmarried patients (p = 0.01). In addition, patients with poor physical activity were more likely to be on the postdialysis phase. Patients with ESRD were characterized with low BMI when compared with patients CKD (t = 3.1, p = 0.004). Conclusion: National CKD and ESRD risk assessment is important in considering primary prevention for CKD progression. At the front line in health care, the nurse can play a vital role in assessing patient’s risk for renal disease progression.

Introduction

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is a major public health problem worldwide; however, it is not adequately presented in Jordanian Ministry of Health reports.Citation1 CKD commonly progresses to end-stage renal disease (ESRD) requiring dialysis or renal replacement therapy. Patients with CKD are high risk for cardiovascular disease and worse outcomes such as mortality and poor quality of life. Although CKD is classified into five stages, only the fifth stage (ESRD) is adequately recognized and formally registered. In Jordan, it is estimated that ESRD accounts for around 3% of the population and keeps increasing each year.Citation1 There are a wide variations in ESRD incidence rates among countries ranging from 6.1% in PortugalCitation2 to 88% in USA.Citation3 Whether this inconsistency reflects differences in risk factors or because of heterogeneity of CKD population is underestimated. There has been a significant amount of interest in behavioral variables as risk factors for CKD progression, given the size of the associated risk and the fact that these variables are extremely preventable.Citation3

The main causes of ESRD in Jordan are hypertension (31%), and diabetes mellitus (20%).Citation1,Citation4 Although additional risks for the progression of CKD such as physical inactivity, smoking and obesity are underestimated in Jordanian patients, they are well appreciated in other populations.Citation2,Citation3 Obesity is highly associated with release of lipolysis products into the systematic circulation in addition to the inflammatory mediators such as cytokines.Citation2 These mechanism may interfere with the engagement of the individual in a healthy lifestyles. Patients with ESRD experience physiological and psychological changes that decrease the ability of the patients to perform physical activity. Physical activity was found to lower the level of inflammatory mediators, improve dialysis adequacy, enhance oxygen uptake and decrease the incidence of cardiovascular diseases among patients with ESRD.Citation5 Evidence demonstrated that directed and supported self-management and healthy behaviors towards chronic illnesses are related to better overall physical and psychological wellbeing.Citation6,Citation7 Further research evidence is calling for early intervention for patients with progressive CKD. These interventions are important to modify health behaviors and retard renal function deterioration. But these interventions will not be helpful in preventing CKD progression unless individualized. Therefore, the goal of this study is to provide an insight specific to Jordan regarding the risk factors for CKD progression that could be associated with the sociodemographic and behavioral characteristics.

Methods

Design

This was a descriptive, cross-sectional, and correlational study that included convenience sample of out-patients with renal diseases recruited from four randomly selected hospitals representing the governmental, teaching, and private sectors. Hospitals were selected randomly from the list of hospitals in each sector.

Study population

The sample was recruited from outpatient departments of the selected hospitals. The inclusion criteria include: (1) at least 18-years-old, (2) have been diagnosed primarily with CKD or ESRD, (3) able to read and write in Arabic. Exclusion criteria include having severe mental, physical or cognitive deterioration. As the patients were recruited from outpatient units, only those who expressed interest to participate in the study were approached in coordination with the institution.

Data collection

Ethical approvals were obtained from the Scientific Research Committee at the Faculty of Nursing-University of Jordan and the targeted hospitals. Patients were screened for eligibility by the primary investigator. Those who met study inclusion criteria were invited to voluntarily participate in the study. Patients gave written informed consent. The letter that was sent to the selected hospitals requested to assign a private room where participants can be interviewed and fill out the requested data. Clinical information was extracted from the patients file.

Measures

Patients were divided into two groups: diagnosed with CKD on the predialysis phase or diagnosed with ESRD receiving dialysis treatment, which was extracted from interviewing the patients and confirmed by assessing the patients' medical files. Patient sociodemographic and clinical variables including age, gender, marital status, employment, monthly income and educational level were extracted from the patients and the medical files. Smoking status was reported by the patients. Smoking per year was calculated based of the following equation: Cigarette Smoking per day (PPD/years smoked) = number of cigarettes smoked/day multiplied by the number of years smoked divided by 20.

Exercise

For the exercise measure, the patients were asked two questions: first, about the number of times they engaged in physical activity in a typical week; second, about the duration they were engaged in a physical activity in a typical week. Researchers recommended assessing the frequency and duration of physical activity through patients' diaries, which were valid indicators or measures of warranted health outcomes such as quality of life in patients with early stages of CKD.Citation7,Citation8

Body mass index

Body mass index (BMI) was calculated from weight and height of the patients. Obesity was defined as body mass index (BMI) ≥25 kg/m2, calculated as body weight (kg)/height2 (m2). In this study, patients were divided into two groups: healthy (BMI < 25 kg/m2) and obese (BMI ≥25 kg/m2).Citation9

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS version 17.0; SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL). An a priori alpha level of 0.05 was used to determine statistical significance. The descriptive statistics were used to test the underlying assumption of normality, linearity, homogeneity, and independence of observations. Patients were divided into predialysis and dialysis groups. Because predialysis and dialysis patients likely differ on some demographic and behavioral characteristics, differences between predialysis and dialysis patients were examined using either two sample t-test or chi-square tests of association, as appropriate. Non-parametric test were used because frequency and duration of physical activity did not meet the requirements of parametric tests. Thus, Mann--Whitney U test was used to compare median of frequency and duration of physical activity across predialysis and dialysis patients.

Results

Data from 161 patients with renal disease were analyzed in this study. Ninety-two (57%) patients were males and 69 (43%) were female. The mean age was 42.2 ± 14.5 (range 19–91). Seventy-five (47%) of the total sample had a monthly income of 500 JD ($700) or less. Most patients were employed and had high school education and above (73%, 74% respectively). The average BMI for the total sample was 26.6 ± 4.9 (19.5–55). Many patients had high BMI: 91 (57%) were overweight (BMI = 25–29.9 kg/m2) and 69 (43%) were in normal range (BMI < 24.9 kg/m2). Seventy-five (47%) of the patients smoked, and 107 (66%) exercised ≥3 times a week. Walking was the most common physical activity performed by the patients 64 (40%) because it is culturally acceptable, cost-effective and simple.

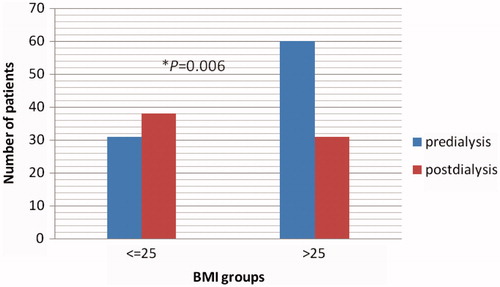

Differences between predialysis and dialysis patients according to demographics and behavioral variables are presented in and . Results revealed significant differences between gender and marital status and progression of renal disease. Patients with ESRD tend to be males compared to patients with CKD on the predialysis phase (p = 0.01). Patients who were married were more likely to have CKD on the predialysis phase, compared to patients with ESRD receiving dialysis and mostly were single, divorced, or widowed. Patients in the ESRD group showed significant lower BMI scores compared to patients with CKD (t = 3.1, p = 0.004) (). Patients in the CKD group were mostly overweight according to their BMI average score (). A Mann–Whitney U test revealed no significant differences in the median of the frequency in physical activity among predialysis (Md = 78, N = 92) and dialysis (Md = 85, N = 69), U = 2869, Z = −1.1, p = 0.3. However, the same test showed significant difference in period of physical activity of predialysis (Md = 74, N = 92) and dialysis (Md = 90, N = 69), U = 2530, Z = −2.2, p = 0.03. This means that patients with ESRD needed longer time to perform their physical activity compared to patients with earlier stages of CKD. Around 59% of the patients on the predialysis phase tend to be nonsmokers, while around 54% of the patients receiving dialysis were current smoker, however, it did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.09) ().

Table 1. Socio-demographic characteristics of predialysis and dialysis patients.

Table 2. Renal disease progression (predialysis and dialysis) according to behavioral variables.

Discussion

To our knowledge this is the first study in Jordan investigating the risk factors for CKD progression. Results from this study suggest that clear differences exist in sociodemographic and behavioral characteristics between predialysis and dialysis Jordanian patients. Patients with ESRD tend to be consistently older,Citation5,Citation10 though, that relationship was almost significant mainly because of the sample size in the present study. Two demographic variables, being male and unmarried (single, divorced, or widow), were shown to account for a significant amount of variance between dialysis and predialysis patients. Although these results in general reflect what has been reported in other studies,Citation5,Citation11 gender differences in ESRD incidence is still not consistence.Citation10–Citation12 This could be explained by the fact that Jordanian men are mostly smokers,Citation13 which may substantially double the risk among them to get ESRD, cardiovascular disease and death, when compared to women.Citation14 Jordan is a developing country and the majority of the hemodialysis population are male, unemployed, and poor which may all compromise their health status and accessibility to medical advice.Citation13,Citation14

Many studies have suggested that important predictors of ESRD include proteinuria, hypertension, hyperglycemia, physical inactivity, obesity, and smoking.Citation5,Citation11,Citation12,Citation16 Smoking and obesity were found to induce proteinuria, albuminuria or decrease estimated glomerular filtration rates among healthy population as well as, patients with CKD in Japan,Citation17 Iran,Citation10 and USA.Citation11 Consistently, the present study found that predialysis patients with CKD had higher BMI scores than the WHO recommendations, but not with patients receiving dialysis. Loss of association between ESRD and obesity suggest that patients with ESRD are mostly exposed to loss of nutrients through dialysis treatment, anorexia, and anemia. On the contrary, it was found that obesity may improve nutritional status and decrease mortality rates among dialysis patients with ESRD.Citation18 These results are consistent with others who found lack of independent risk of obesity for progression of CKD on Iranian patients diagnosed with late stages of CKDCitation5 and Japanese patients on the early stages of CKD.Citation17 BMI is the main and valid adiposity measurement by WHO and highly associated with cardiovascular diseases and death. However, studies have shown that anthropometric obesity measures such as waist circumference had more ability to classify obesity and was associated with CKD, especially when combined with BMI.Citation19 This study showed that obesity among patients with CKD may predict ESRD incidence in Jordanian patients.

Regular exercise was found to reduce blood pressure and inflammation thus improves the outcome in patients with CKD by slowing the loss of renal function.Citation20 Previous studies found exercise levels were low among patients with CKD in comparison with patients receiving hemodialysis. Interdialytic exercise was applied for patients during their hemodialysis sessions. Researchers found interdialytic exercise safe, reducing fatigue, and time-saving, when compared to aerobic and resistance exercises that were performed away from the dialysis units.Citation6 The present study showed that patients with CKD spent less time on exercising compared with dialysis patients. Lack of motivation was the most frequently and intensely experienced barrier found by other researchers, not the physical and psychological stressors experienced by being on dialysis.Citation21,Citation22 There is limited research evidence supporting the benefits of exercise among patients with early stages of CKD compared with patients with ESRD.Citation8

Limitations of the present study are the small sample size and the one-point of measurement that may obscure the relationship between study variables and CKD progression. Further, bias or distortion of the past events recall is highly associated with self-reporting assessment.

Conclusion

Patients with ESRD or CKD are presented with other chronic disease for which exercising, smoking cessation and weight control are highly beneficial and warranted. Efforts should be directed to identify negative health behaviors in patients with renal disease by utilizing multidimensional approaches and personnel.Citation23 Nephrologists and nephrology nurses are rarely screen or assess patients with CKD for unhealthy behaviors or provide the patients with advice about lifestyle modifications. Effort should not only be directed to increase life expectancy of patients with ESRD, but also to prevent the speed in the transition of CKD progression and ESRD development.Citation24 The nephrologist nurse should consider the unique individual characteristics of each patient. Factors such as elderly, males, unmarried, smokers, physically inactive, and overweight have greater risk of CKD progression.Citation25

A national CKD progression screening among Jordanian patients is a major health need. Many countries around the world conducted their CKD detection program to identify disease parameters, and to increase the awareness of kidney disease risk and complications.Citation26,Citation27 The present study was able to screen for risk factors for CKD progression to ESRD at one-point of measurement. Repeated follow-up and continuous screening studies including larger sample size can be more beneficial for Jordanian population.Citation26 Understanding risk factors for CKD progression can shed light on educational and counseling intervention strategies and policies to prevent CKD progression to ESRD.

Declaration of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

References

- The Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan Ministry of Health, Non-communicable Disease Directorate. National Registry of End Stage Renal Disease Annual Report; 2008. Available at: ww.moh.gov.jo Accessed April 13, 2013

- Vinhas J, Gardete-Correia L, Boavida JM, et al. Prevalence of chronic kidney disease and associated risk factors, and risk of end-stage renal disease: data from the PREVADIAB study. Nephron Clin Pract. 2011;19:c35–c40

- Onuigbo M. Syndrome of rapid-onset end-stage renal disease: a new unrecognized pattern of CKD progression to ESRD. Renal Fail. 2010;32:954–958

- Khalil A, Darawad M, Algamal E, Mansour, A. Predictors of dietary and fluid nonadherence in Jordanian patients with end-stage renal disease receiving hemodialysis: a cross-sectional study. J Clin Nurs. 2012;22:127–136

- Tohidi M, Hasheminia M, Mohebi R, et al. Incidence of chronic kidney disease and its risk factors, results of over 10 year follow up in an Iranian cohort. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(9):e45304

- Chang Y, Cheng S, Lin M, Gau F, Chao Y. The effectiveness of interdialytic leg ergometry exercise for improving sedentary life style and fatigue among patients with chronic kidney disease: a randomized clinical trial. Int J Nurs Stud. 2010;47:1383–1388

- Wei S, Chang Y, Mau L, et al. Chronic kidney disease care program improves quality of pre-end-stage renal disease care and reduces medical costs. Nephrology. 2010;15:108–115

- Kosmadakis G, John S, Clapp J, et al. Benefits of regular walking exercise in advanced pre-dialysis chronic kidney disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2012;27:997–1004

- National Institutes of Health and National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute: Clinical Guidelines on the Identification, Evaluation, and Treatment of Overweight and Obesity in Adults: the Evidence Report. NIH Publication 98-4083; June 1998

- Najafi I, Attari F, Islami F, et al. Renal function and risk factors of moderate to severe chronic kidney disease in Golestan province, Northeast of Iran. PLoS ONE. 2010;5(12):e14216

- Travers K, Martin A, Khankhel Z, Boye K, Lee L. Burden and management of chronic kidney disease in Japan: systematic review of the literature. Int J Nephrol Renovasc Dis. 2013;6:1–13

- Goto M, Wakai K, Kawamura T, Ando M, Endoh M, Tomino Y. A scoring system to predict renal outcome in IgA nephropathy: a nationwide 10-year prospective cohort study. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2009;24:3068–3074

- The Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan Department of Statistics. 2010. Retrieved 6/7/2013. Available at: http://www.dos.gov.jo/dos_home_a/main/Analasis_Reports/Smoking_2010/Smoking_2010.pdf

- Batieha A, Abdallah S, Maghaireh M, et al. Epidemiology and cost of hemodialysis in Jordan. La Revue de Sante de la Mediterranee orientale. 2007;13:654–663

- Stack A, Murthy B. Cigarette use and cardiovascular risk in chronic kidney disease: an unappreciated modifiable lifestyle risk factor. Sem Dial. 2010;23:298–305

- Kato S, Nazneen A, Nakashimi Y, et al. Pathological influence of obesity on renal structural changes in chronic kidney disease. Clin Exp Nephrol. 2009;13:332–340

- Yoshida T, Yakei T, Shirota S, et al. Risk factors for progression in patients with early-stage chronic kidney disease in the Japanese population. Int Med. 2008;47:1859–1864

- Zocalli C. The obesity epidemic in ESRD: from wasting to waist? Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2009;24:376–370

- Burton J, Gray L, Webb D, et al. Association of anthropometric obesity measures with chronic kidney disease risk in a non-diabetic patient population. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2012;27:1860–1866

- Svarstad E, Myking O, Ofstad J, Iversen M. Effect of light exercise on renal hemodynamics in patients with hypertension and chronic renal disease. Scand J Urol Nephrol. 2002;36:464–472

- Goodman E, Ballou M. Perceived barriers and motivators to exercise in hemodialysis patients. Nephrol Nurs J. 2004;31:23–29

- Cheema B, Singh M. Exercise training in patients receiving maintenance hemodialysis: a systematic review of clinical trials. Am J Nephrol. 2005;25:352–364

- Orlando L, Belasco E, Patel U, Matchar D. The chronic kidney disease model: a general purpose model of disease progression and treatment. BMC Med Informat Decision Making. 2011;11:41

- Moinuddin I, Leehey D. A comparison of aerobic exercise and resistance training in patients with and without chronic kidney disease. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2008;15:83–96

- Bagchi S, Agarwal S, Gupta S. Targeted screening of adult first-degree relatives for chronic kidney disease and its risk factors. Nephron Clin Pract. 2010;16:128–136

- McCullough P, Brown W, Gannon M, et al. Sustainable community-based CKD screening methods employed by the National Kidney Foundation's Kidney Early Evaluation Program (KEEP). Am J Kidney Dis. 2010;57:S4–S8

- Mathew T, Corso O. Review article: early detection of chronic kidney disease in Australia: which way to go. Nephrology. 2009;14:367–373