Abstract

Palliative care (PC) training and experience of United States (US) adult nephrology fellows was not known. It was also not clear whether nephrology fellows in the US undergo formal training in PC medicine during fellowship. To gain a better understanding of the clinical training and experience of US adult nephrology fellows in PC medicine, we conducted a national survey in March 2012. An anonymous on-line survey was sent to US adult nephrology fellows via nephrology fellowship training program directors. Fellows were asked several PC medicine experience and training questions. A total of 105 US adult nephrology fellows responded to our survey (11% response rate). Majority of the respondents (94%) were from university-based fellowship programs. Over two-thirds (72%) of the fellows had no formal PC medicine rotation during their medical school. Half (53%) of the respondents had no formal PC elective experience during residency. Although nearly 90% of the fellows had a division or department of PC medicine at their institution, only 46.9% had formal didactic PC medicine experience. Over 80% of the respondent's program did not offer formal clinical training or rotation in PC medicine during fellowship. While 90% of the responding fellows felt most comfortable with either writing dialysis orders in the chronic outpatient unit, seeing an ICU consult or writing continuous dialysis orders in the ICU, only 35% of them felt most comfortable “not offering” dialysis to a patient in the ICU with multi-organ failure. Nearly one out of five fellows surveyed felt obligated to offer dialysis to every patient regardless of benefit. Over two-thirds (67%) of the respondents thought that a formal rotation in PC medicine during fellowship would be helpful to them. To enhance clinical competency and confidence in PC medicine, a formal PC rotation during fellowship should be highly considered by nephrology training community.

Introduction

With an increasing aging population, practicing nephrologists are now faced with taking care of elderly advanced renal disease patients with multiple comorbidities. Nephrologists taking care of these patients need to understand and appreciate issues related to renal palliative care (PC).Citation1 Are nephrologists prepared for dealing with end-of-life and renal PC for their advanced kidney disease patients? They often come across situations where decision-making about withdrawal of dialysis and end-of-life symptom management are essential parts of care. Nephrologists are also often confronted with issues of initiation of dialytic therapy in terminally ill patients. Despite knowing that a given terminally ill patient may not benefit from dialytic therapy, practicing nephrologists are often consulted for offering dialysis to a dying patient. While discussions about end-of-life and renal PC for patients with advanced kidney disease should begin sooner rather than later, most nephrologists report feeling unprepared to make such conversations.Citation2 This could be a result of no or suboptimal experience in PC medicine during fellowship training. Practicing nephrologists are increasingly aware that palliative care does not only mean end-of-life management but rather an overall supportive advance care planning that is provided over time to their dialysis patients.Citation2

Clinical practice guidelines on appropriate initiation and withdrawal of dialysis have been created by nephrology societies.Citation3 Core curriculum in renal PC has also been developed.Citation4 However, it was not known if training in PC medicine was adequately provided during nephrology fellowship in the United States (US). A national survey conducted nearly ten years ago concluded that end-of-life training during nephrology fellowship was inadequate.Citation5 The authors of that survey also suggested that end-of-life training was needed during nephrology fellowship and that education in PC medicine be incorporated into fellowship program curriculum.Citation5 It was not clear whether this recommendation was considered by the nephrology training community. Over the years, as formal experience in PC medicine has become more available to training programs in the US, we wanted to know if US adult nephrology fellows underwent formal training in PC medicine during their fellowship. We also wanted to determine the comfort level of nephrology fellows on PC related issues. In addition, while training in PC might be evident in many US medical schools, most of our graduating fellows in nephrology currently are international medical graduates (IMGs). It is unclear what level of PC training do IMGs receive. We also wanted to know if fellows prior to entering the fellowship program had received any formal training in PC during their medical school or residency training. Hence, to better understand the PC training and experience of US adult nephrology fellows, we conducted a national survey.

Methods

To gain greater insight into nephrology fellows’ PC training and experience, we conducted a national online survey from March to June 2012. The survey was deemed exempt by the institutional review board at our institution (North Shore-Long Island Jewish Health System). The survey was initially distributed to US adult nephrology fellows via US nephrology fellowship training program directors in March 2012. Survey reminders were subsequently sent in May and June 2012. This anonymous online survey consisted of several PC training and experience questions (). Only nephrology fellows in US training programs were eligible to participate. The survey was voluntary and allowed respondents to skip questions that they preferred not to answer. The survey was closed on June 30, 2012.

Table 1. Palliative care experience of US adult nephrology fellows: survey questions.

Results

A total of 105 US adult nephrology fellows responded to our survey. This represented approximately 11% of the total numbers of fellows enrolled in US nephrology fellowship programs in 2011–12.

Respondent characteristics

Majority (62%) of the respondents were either second or third year fellows. Ninety-four percent of the respondents were from university-based fellowship programs. The remaining (6%) respondents were from community hospital-based programs. Nearly half of the respondents (48%) were undergoing fellowship training in northeast US. The remaining fellows were undergoing training either in western (15%), mid-western (13%) or southern US (23%). While 62% of the respondents were IMGs, remaining 38% completed their medical school training in the US. Seventy percent of the respondents were in the 31–35 years age group. The remaining respondents were either in the 26–30 years (15%) age group or were above 35 years (15%) of age. Sixty-three percent of the respondents were male. Respondents came from various ethnicities including Caucasian (27%), African American (2%), Latino (4%), Asian (40%), South East Asian (20%) and others (7%). Religious preferences of the respondents included: Christianity (28%), Hinduism (21%), Islam (11%), Buddhism (4%), Judaism (6%), Sikhism (4%) and other (3%). Twenty-three percent of the respondent had no religious preference.

Participation in a formal palliative care rotation during medical school, residency and fellowship

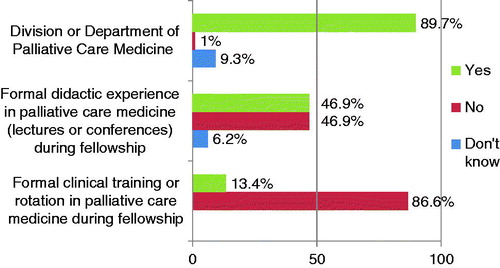

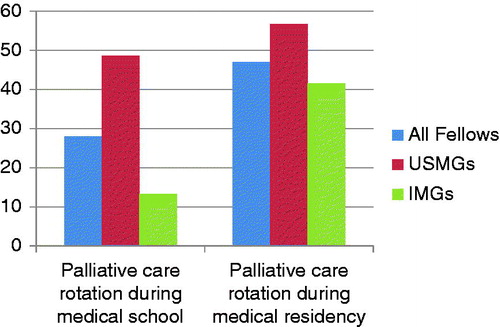

Most (72%) of the responding fellows did not participate in a formal PC medicine rotation during their medical school. Over half (53%) of the respondents had no formal training in PC medicine during residency. Of the remaining 47% who did have a formal PC experience during their residency, 20% of them had a four week rotation in PC, 17% had a two week, 6% had one week and 4% had longer than four week PC rotation experience. Although nearly 90% of the fellows had a division or department of PC medicine at their institution, only 46.9% had formal didactic (meaning core curriculum lectures and/or conferences) PC medicine experience during their fellowship training (). At the time of the survey, nearly 87% of the respondent's program did not offer formal clinical training or rotation in PC medicine during fellowship (). Further analysis of our survey suggested that 86.7% of the IMGs and 51.4% of US medical graduates (USMGs) did not undergo any formal training in PC medicine during their medical school. 58.4% of the IMGs and 43.3% of USMGs did not undergo any formal PC rotation during medical residency ().

Comfort with palliative care issues during fellowship training

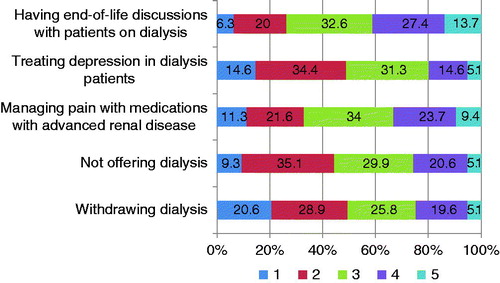

While the overwhelming majority (90%) of the responding fellows felt most comfortable with either writing dialysis orders in the chronic outpatient unit (97%), seeing an ICU consult (94%), or writing continuous dialysis orders in the ICU (89%), only one-third (35%) felt most comfortable “not offering” dialysis to a patient in the ICU with multi-organ failure. Comfort levels on palliative care related issues are shown in . Nearly one out of five (18%) fellows surveyed felt obligated to offer dialysis to every patient regardless of benefit.

End-of-life discussions during fellowship training

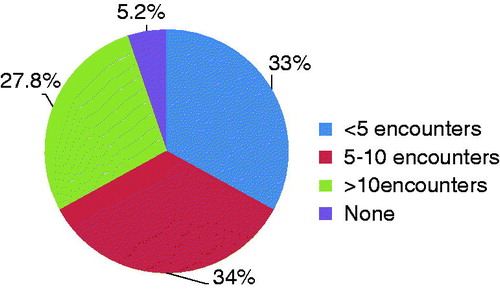

shows the numbers of end-of-life patient encounters fellows had with patients with advanced kidney disease during fellowship. Two-thirds of fellows had either less than 5 patient encounters (33%) or 5–10 patient encounters (34%). Nearly 28% of fellows had more than 10, while 5.2% had no end-of-life patient discussion.

Perceived benefits of palliative care rotation during fellowship training

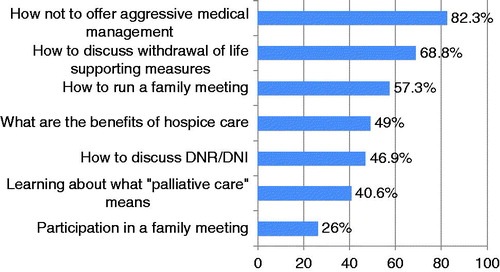

Two-thirds (67%) of the respondents thought that a formal rotation in PC medicine during their fellowship would be helpful to them. When asked on the duration of such an experience, majority of this group felt that a two-week rotation in PC medicine (based on the free comment section responses) during their fellowship training would be helpful. Only 9% of the respondents felt that a formal PC rotation would not be of benefit. While 13% of the respondents said that they already had or were scheduled for PC rotation during their fellowship, another 10% did not know if a PC rotation would be of benefit to them. Most respondents felt that they would most benefit from learning “how not to offer aggressive medical therapy” (82.3%) and “how to discuss withdrawal of life supporting measures” (68.8%) from a formal PC rotation during their fellowship (). Other suggested benefits of such a rotation included: how to run a family meeting (57.3%), discuss DNR/DNI (46.9%), benefits of hospice care (49%), and learn about what “palliative care” means (40.6%).

Discussion

Nephrologists in practice dedicate a significant percentage of their time providing care to patients with end-stage renal disease. Nephrologists may also be confronted with issues related to PC medicine as a significant percentage of dialysis patients stop dialysis prior to death.Citation6 In the last several years, the field of geriatric nephrology and renal PC has evolved with research suggesting the need for this experience to be an integral part of nephrology fellowship training. Tamura et al.Citation7 demonstrated that there was a significant and sustained decline in functional status among elderly nursing home residents after being initiated on dialysis. In addition, studies done on dialysis patients have shown that older age, comorbidities, poor functional and nutritional status are major risk factors for death after initiating dialysis.Citation8 Moss et al.Citation9 in their study found that the “surprise” question “Would I be surprised if this patient died in the next 12 months?” was also effective in identifying sicker dialysis patients with higher mortality. Despite having the abilities to identify advanced kidney disease patients with higher mortality, discussions about end-of-life and renal PC, especially withdrawing and withholding dialysis are often perceived as difficult to initiate and therefore often avoided. With growing older dialysis population, nephrologists of today’s generation should be knowledgeable about renal PC and should also feel comfortable with these difficult conversations.

A national survey conducted in 2002 determined that majority of graduating nephrology fellows had inadequate end-of-life experiences during their fellowship training.Citation5 Both the quantity and quality of teaching that the responding fellows received on PC medicine was significantly lower than other topics in nephrology.Citation5 As a result, it is likely that the group of graduating fellows at that time were less prepared to provide renal PC to their terminally ill patients. Since Holley and colleagues published their survey results in 2003,Citation5 it was unclear if any major changes were made in nephrology fellowship programs to accommodate PC curriculum for the fellows. Hence, we conducted our survey to determine if nephrology fellowship programs had embraced any of these recommendations in PC medicine as suggested by Holley and colleagues, nearly 10 years ago.Citation5 In contrast to the previous survey, our survey also determined if nephrology fellows had received any formal training in PC medicine prior to entering their fellowship. While most responding fellows did not receive any formal training during their medical school, nearly half of them did undergo some formal PC rotation during their medical residency. For those who underwent formal PC training during their residency, nearly half of fellows underwent 2 or less weeks of training. Our survey also wanted to determine if the fellows had a division or department of palliative care at their institution. Most of the respondents had a division or department of palliative care medicine at their institution, however majority of the responding fellows did not receive any formal didactic (lectures and/or core curriculum conferences) PC experience during their fellowship. Most of the respondents’ programs also did not offer formal rotation or clinical training in PC medicine during fellowship.

We also wanted to know the comfort level of fellows with palliative care issues. Only, one-third of the fellows surveyed felt most comfortable withholding dialysis in a terminally ill ICU patient. One out of five fellows surveyed felt obligated to offer dialysis to every patient regardless of benefit. We also wanted to know the numbers of end-of-life encounters each fellow had during their fellowship. Nearly four out of each 10 fellows surveyed had less than 5 such encounters at the time of this survey. It is likely that fellows who were less comfortable with end-of-life issues were the ones who had fewer end-of-life discussions.

What can be done to enhance PC experience during nephrology fellowship? Based on our survey results, it seems likely that the recommendations to incorporate PC into nephrology training programs made by Holley and colleagues nearly 10 years ago were not widely implemented by the US nephrology training community.Citation5 Clearly, our fellows need much more experience and training in renal PC medicine during fellowship. Our survey findings also suggest that most fellows entering fellowship have no prior formal experience in PC medicine. Hence, nephrology fellowship program directors should consider a formal PC training for their fellows during their fellowship training as this may lead to improved comfort and communication skills in end-of-life care. As interest in pursuing a career in nephrology continues to decline,Citation10 especially among US medical graduates (USMGs), nephrology fellowships programs are likely to train more IMGs. Our survey results also showed that IMGs were less likely to have undergone formal PC training during their medical school or residency when compared to USMGs. Hence, a formal training should be strongly considered for those fellows who have had no previous PC experience.

Most respondents on our survey felt a formal rotation in PC medicine would be helpful to them. Many fellows felt that a dedicated 2-week PC rotation would be helpful. Based on the survey findings, since this past year, we at our institution (North Shore University Hospital and Long Island Jewish Medical Center) have incorporated a 2-week formal PC rotation in our fellowship program. This effort is in conjunction with the dedicated palliative care team at our institution. So far, as we continue to evaluate this experience, our fellows have provided excellent and positive feedback about this dedicated rotation.

In our survey, we also found that over half of the respondents had no formal didactic sessions on PC medicine during their fellowship. Training program directors should ensure that dedicated core curriculum lectures on renal PC medicine are being instituted regularly for their fellows at their institution. Interdisciplinary case conferences to discuss topics like “end-of-life care in patients undergoing chronic dialysis” should also be considered during fellowship training. summarizes resources that are available for faculty and trainees in renal palliative care.

Table 2. Resources for faculty and trainees on renal palliative care.

Nephrology fellows are also facing a challenge in communication skills. Our survey also suggests that there may be a high percentage of US nephrology fellows that have limited skills in how to offer conservative as opposed to aggressive therapy, how to run a family meeting or discuss palliative care measures to a patient or their family. The implementation of communication workshop into the training curriculum can be an ideal option. A communication skills workshop for nephrology fellows termed, “NephroTalk”, focused on delivering bad news and helping patients define care goals, including end-of-life preferences.Citation11,Citation12 “NephroTalk” was a 4-hour workshop that included teaching didactics and practice sessions with standardized patients. Pre- and post-workshop surveys evaluated the efficacy of the curriculum. During this exercise, the mean level of preparedness increased significantly for all skills, including delivering bad news, expressing empathy, and discussing dialysis initiation and withdrawal.Citation11,Citation12 All respondents reported they would recommend this training to other fellows. Creating a structure for implementing communication workshops and how to replicate the format can differ from center to center. Written communication evaluation methods using clinic lettersCitation13 and random fellow clinic notes have been utilized by several training programs.Citation14 Fellowship programs that have access to simulation center in their institution should also consider an Objectively Structured Clinical Examination (OSCE) in PC medicine. Workshops like “NephroTalk” and others that have been shown to enhance communication skills to the unique issues faced in nephrology should be considered in all fellowship programs. A structured curriculum that included a case-based debriefing has also been shown to improve confidence in discussing and providing end-of-life and palliative care to patients in the intensive care unit setting.Citation15 It is hoped that as a result of some or all of these interventions and others, training programs will enhance the PC experience of nephrology fellows.

We also acknowledge that there may be may be limitations to the data we have collected. Compared to the survey done in 2002, our sample size was smaller (11% response rate) and as a result might not have been representative of the fellow group and training programs as a whole. Potential bias created by the low response rate may limit the generalizability of the survey results. Having program directors distribute the survey to their fellows may have resulted in some fellows feeling obligated to participate in the survey process. It is plausible that fellows that did not receive experience in PC medicine might be motivated to respond to our survey. Furthermore, the overall content of the survey did not address the PC and end-of-life attitudes of the supervising nephrology attendings or mentors. It is plausible that some of the supervising faculty members do not feel comfortable discussing end-of-life issues with patients or their trainees and that this would reflect on their trainee’s experience. Another factor that might be important is the respondents' own personal family experience with end-of-life, which has been noted to be an important factor in development of attitudes towards end-of-life care in their patients.Citation16 We nevertheless feel that even if this was the case, the insights into PC experience that this group can provide are invaluable if we are to improve PC training during fellowship. It is also hoped that this enhanced PC experience during fellowship training will better prepare fellows to deal with the critical task of shared decision-making with patients and their families.

Conclusions

Majority of the responding fellows did not undergo formal clinical rotation in PC medicine during fellowship. Nearly half of responding fellows did not have formal didactic PC medicine experience during fellowship. To enhance clinical competency and confidence in PC medicine, a formal PC rotation during fellowship should be highly considered by nephrology training community and fellowship program directors.

Declaration of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the nephrology training program directors throughout the U.S. to whom we are indebted for their assistance in carrying out this study. We like to thank Dr. Tanveer Mir (palliative care medicine attending) for her assistance in helping us design some of the survey questions. We also like to thank Dr Vipulbhai Sakhiya for his assistance in analyzing some of our survey results. Results of this study were presented at the American Society of Nephrology Kidney Week 2012 in San Diego, California.

Dr. Hitesh H. Shah is the Director of Nephrology Fellowship Program at the Hofstra North Shore-LIJ School of Medicine. Dr. Divya Monga was a nephrology fellow at the Hofstra North Shore-LIJ School of Medicine. Dr. April Caperna is a palliative care medicine attending at the Hofstra North Shore-LIJ School of Medicine. Dr. Kenar D. Jhaveri is the Internal Medicine Clerkship Director at the Hofstra North Shore-LIJ School of Medicine.

References

- Neely KJ, Roxe DM. Palliative care/hospice and the withdrawal of dialysis. J Palliat Med. 2000;3:57

- Holley JL. Palliative care in end-stage renal disease: focus on advance care planning, hospice referral, and bereavement. Semin Dial. 2005;18(2):154–156

- Renal Physicians Association and American Society of Nephrology. Shared Decision-making in the Appropriate Initiation and Withdrawal from Dialysis. Clinical Practice Guideline 2. Washington, DC: Renal Physicians Association and American Society of Nephrology; 2000

- Moss AH, Holley JL, Davison SN, et al. Palliative care. Am J Kidney Dis. 2004;43(1):172–173

- Holley JL, Carmody SS, Moss AH, et al. The need for end-of-life care training in nephrology: national survey results of nephrology fellows. Am J Kidney Dis. 2003;42(4):813–820

- Cohen LM, Germain M, Poppel DM, et al. Dialysis discontinuation and palliative care. Am J Kidney Dis. 2000;36:140

- Kurella Tamura M, Covinsky KE, et al. Functional status of elderly adults before and after initiation of dialysis. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(16):1539–1547

- Holley JL. Palliative care in end-stage renal disease: illness trajectories, communication, and hospice use. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2007;14:402

- Moss AH, Ganjoo J, Sharma S, et al. Utility of the surprise question to identify dialysis patients with high mortality. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;3(5):1379–1384

- Shah HH, Jhaveri KD, Sparks MA, Mattana J. Career choice selection and satisfaction among US adult nephrology fellows. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;7(9):1513–1520

- Schell JO, Arnold RM. NephroTalk: communication tools to enhance patient-centered care. Semin Dial. 2012;25(6):611–616

- Schell JO, Green JA, Tulsky JA, Arnold RM. Communication skills training for dialysis decision making and end of life care in nephrology. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013;8(4):675--680

- Mahan J, Hains DS, Patel HP. Development of a validated nephrology clinic letter fellow competency assessment. J Am Soc Nephrol (Abstract). 2011;22:TH-PO853

- Thomas LF, Norby SM. Validating peer chart audit in a nephrology fellow continuity clinic setting. J Am Soc Nephrol (Abstract). 2010;21:TH-PO828

- Seoane L, Bourgeois DA, Blais CM, Rome RB, Luminais HH, Taylor DE. Teaching palliative care in the intensive care unit: how to break the news. Ochsner J. 2012;12(4):312–317

- Perry E, Swartz R, Smith-Wheelock L, Westbrook J, Buck C. Why is it difficult for staff to discuss advance directives with chronic dialysis patients? J Am Soc Nephrol. 1996;7(10):2160–2168