Abstract

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is a world-wide public health problem. The purpose of this study was to identify the role of some controversial potential risk factors in development of CKD. “Community Complex Health Screening” is a large-scale, free, health program for individuals ≥40 years of age that has been available since January 2002 in Chiayi County, Taiwan. A questionnaire was administered to study participants, collecting information on ethnicity, use of analgesics, and life habits. Age, sex, and blood biochemical analyses were considered as potential confounders. A high prevalence and low awareness of CKD were noted in this population. Females with CKD had a lower awareness of their illness than males. Analgesic users had a significantly lower estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR). Age (OR = 1.095), females (OR = 0.348), fasting plasma glucose (OR = 1.005), level of uric acid (UA) (OR = 1.517), and analgesic usage (OR = 1.512) remained independent predictors of CKD. Multivariate linear regression found that use of analgesics, father’ clan from Fujian, mother’ clan from Fujian, and coffee intake were independent determinants of renal outcome with coefficient of regression (β) of −0.102, −0.192, 0.210 and 0.88, respectively. The prevalence of CKD decreased with advanced education. Further, there was no significant difference between education background and analgesics use. In conclusion, analgesic use, parents’ clan, and coffee intake were independent risk factors for CKD in middle-aged and elderly Taiwanese. Thus, an effective educational program that increases the awareness of such individuals residing in rural counties is warranted.

Introduction

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is a world-wide public health problem. There is an increasing incidence of patients with renal failure undergoing maintenance dialysis therapy. In 1997, the total cost of care for end-stage renal disease (ESRD) patients, who constitute only 0.5% of the Medicare population, was over $15 billion, which was expected to increase to $28 billion by 2010.Citation1,Citation2 The main source of growing expenditure appears to be the overall increase in number of patients with ESRD and acceptance of patients with high co-morbidity into the program.Citation3 In Taiwan, the tremendous expense for this care has become a great burden to the healthcare system. Taiwan’s National Health Insurance (NHI) spent about 7.1% of the total NHI expenditure, caring for 0.15% of the ESRD population in 2003. Using appropriate strategies, the progression of the disease can be delayed and the complications arising from decreased kidney function can be better controlled.Citation4,Citation5 Detection of patients either in the earlier stages of CKD or at risk of CKD progression effectively reduces the growing socioeconomic burden. Recently, the authors of this study collaborated with the Public Health Bureau of Chiayi County in Taiwan to analyze the underlying mechanism of CKD and reported that hypertriglyceridemia and hyperuricemia were independent risk factors.Citation6,Citation7 On the basis of this co-operation, this study will further help to establish a local database of CKD utilizing the most updated data of Community Complex Health Screening in Chiayi County in Taiwan, including all information from the well-designed questionnaire.

The very high prevalence of CKD and incidence of ESRD in Taiwan makes the study of risk factors for CKD a high priority issue in Taiwan’s health care system. Kuo et al. analyzed Taiwanese NHI dataset and suggested that advanced age, diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and females were associated with a higher risk of developing CKD.Citation8 Wen et al. further demonstrated that smoking and obesity were more common in the CKD group.Citation3 However, the presence of those co-morbid conditions did not fully explain the risks of CKD in Taiwan, suggesting that other potential risks in Taiwan needed to be explored, including use of analgesics, family history (either genetic susceptibility or environmental factors), and other non-biomedical factors, such as caffeine and alcohol intake, smoking, bet-nut use, and socioeconomic status.Citation9–12

Musculoskeletal pain was much more prevalent in CKD patients (72.9%) compared with non-CKD patients (9%).Citation13 That illness might lead to more analgesics use, including acetaminophen, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, narcotics, or even combination therapy. Unfortunately, chronic use of analgesics is believed to be harmful to the kidney. A recent cohort study using the Taiwanese NHI database indicated exacerbating effects of analgesics on CKD in a dose-dependent manner.Citation14 A study of 4,365 dialysis patients treated in Georgia, North Carolina, and South Carolina during a single year found that 20% reported having a first- and second-degree relative with ESRD.Citation15 Hence, the authors of this study speculated that regular use of analgesics, ethnicity disparities, family history of either CKD or ESRD, and poor socioeconomic status might be associated with either the progression or development of CKD. Those emerging potential risk factors increased our awareness to new, high risk groups, and important information such as smoking; coffee intake; marital status; education; income; analgesic use; history of herbal therapy and other regular medications; family history of CKD, ESRD, diabetes mellitus or hypertension, etc., could be obtained from a well-designed questionnaire using the Community Complex Health Screening Program in Chiayi County. The purposes of this study were to address the role of analgesics, parents’ clan background, and other nonbiomedical factors (such as coffee, tea, and alcohol intake, smoking, bet-nut uses, and educational background) on the development of renal deterioration in a large, community-based, cross-sectional medical screening survey, to analyze the importance of serum uric acid (UA) levels for CKD, and to describe the possible causes of late-stage CKD in an ESRD endemic county.

Methods

Subjects

Community Complex Health Screening is a large, free health program for people ≥ 40 years of age that has been offered since January 2002 in Chiayi County, Taiwan. To facilitate “early detection for early treatment,” the Public Health Bureau of Chiayi County selected one township every month where community resources were combined to conduct the Community Complex Health Screening program.

Questionnaires

All questionnaires were completed with the assistance of trained nurses and collected information regarding patient age, sex, body measurements (body weight and body height), ethnicity, family history of diabetes mellitus (DM), hypertension (HTN), any known renal disease or ESRD, past medical history, and smoking and drinking habits. Past history of DM, HTN, renal failure, and the use of drugs were pursued. The question about ethnicity was “Where is your ancestry from, Fujian, Hakka or Indigenous people?” Smoking was coded as “yes/no” (yes was defined as more than 0.5 pack/day for more than 10 years). Alcohol drinking was coded as “yes/no” (Students were asked the following question about their alcohol use: “How often have you had 5 or more drinks of alcohol on one occasion?” Response categories were 0 = “never,” 1 = “once,” 2 = “2 to 5 times,” or 3 = “5 times.” Students who reported never were classified as “no” and all others as “yes.”). The question for history of DM was “Have you been diagnosed as having DM (also called “a disease with sugar in urine” in lay terms) by a physician?” The question for history of HTN was “Have you been diagnosed as having hypertension (also called “high blood pressure” in lay terms) by a physician?” Questions for history of renal failure or disease were “Do you have physician-diagnosed renal disease or renal failure?” The question for medication use was “What is (are) your medication(s) on a regular basis?” Analgesic therapy was coded as “yes/no” and identified by the specified medication names, which were composite names. Herbal therapy was coded as “others” and identified by the specified herbal names. Marital status was coded as “single/married/divorced/widow or widower.” Educational levels were represented by a five-category variable: whether participants did or did not graduate from elementary school/ junior high school/ senior high school/ college or university/ graduate school.

Measurements

Participants underwent routine physical health examinations and laboratory testing for common adult diseases such as hypertension, diabetes, kidney disease, hyperuricemia, and hypercholesterolemia. Standardized laboratory testing for all Chiayi county participants was conducted by a single regional laboratory of the Health Bureau of Chiayi County’s Laboratory Services. Several anthropometric and physical measurements were assessed such as height, weight, and blood pressure. Blood pressure was measured using a mercury sphygmomanometer after resting for at least 5 minutes in a sitting position. Two measurements were made 60 s apart. If the two measurements differed by > 10 mm Hg, a third measurement was made and the two closest blood pressure values were averaged. Serum collection was performed at a mobile examination center, and the participants were asked to fast overnight for at least 12 h. Fasting plasma glucose (FPG), triglyceride, cholesterol, UA, and creatinine were measured using a Technicon RA-1000 analyzer (Bayer, Leverkusen, Germany).

Definition of CKD

CKD was classified according to the National Kidney Foundation Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative guidelines.Citation16 An abbreviated Modification of Diet in Renal Disease equation was used to calculate estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) values (measured in mL/min/1.73 mCitation2): 186.3 × [serum creatinine (mg/dL)]−1.154 × age (in years)−0.203 × (0.742 for women). CKD was defined by either the presence of markers of kidney damage in urine or blood or an eGFR < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2. Patients with CKD stage 3 were defined as those with eGFR values between 30 mL/min/1.73 m2 and 60 mL/min/1.73 m2. CKD stage 4 was defined as eGFR values of 15–29 mL/min/1.73 m2, and a cutoff value of < 15 mL/min/1.73 m2 was used to define CKD stage 5.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were expressed as mean ± standard deviation. Analysis of dependency for categorical data in two-way tables was performed by fisher’s exact test for small samples. Comparisons between groups were by student’s unpaired t test for parametric and Mann–Whitney U test for non-parametric variables. Significance was assigned at the p < 0.05 levels. Multivariable logistic regression analyses were used to evaluate the relationship between ethnicity, analgesic therapy, family histories, demographic factors, comorbid conditions, and CKD. Multiple linear regression analyses were performed to determine the associated factors that might significantly influence eGFR. A p value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical calculations were performed using SPSS software (version 13.0 for Windows; SPSS, Chicago, IL).

Results

High prevalence and low awareness rate of CKD

Of the 35,071 subjects enrolled in the study, 22,665 had complete data sets that were analyzed. The demographic and clinical characteristics of the study population have been summarized in . The prevalence of hypertension and diabetes were 61.3% and 17.9%, respectively. Notably, 6.2% of this population (no significant difference in terms of gender) used potentially nephrotoxic medications that included usage of analgesics. The overall awareness rate was 34.7% in this population. Females with CKD had a lower awareness of their illness than their male counterparts (34.1% vs. 35.5%, respectively). Among participants with stage 3, stage 4 or stage 5, the awareness rate of CKD was 0.9%, and 9.6%, respectively.

Table 1. Characteristics of the study participants with and without late-stage CKDa.

Demographic characteristics of middle and elderly subjects compared by use of analgesics

lists demographic variables for study subjects according to either the presence or absence of analgesic use. Compared with nonregular users of analgesics, regular users were significantly older, had hypertension and diabetes, were male, had a higher BMI, higher mean systolic blood pressure, and higher FPG. The mean level of serum creatinine was slightly higher in regular analgesic users compared with nonregular analgesic users. As for eGFR measurements, regular analgesic users had a significantly lower eGFR compared with nonregular users of analgesics.

Table 2. Comparisons of demographic characteristics on the exposure or non-exposure to analgesicsa.

Impact of analgesic use on renal outcome

shows the odds ratios (Ors) for late-stage CKD based on demographic and biochemical variables. All ORs were statistically significant, with the exception sex (p < 0.01). In multivariate logistic regression analysis, age (OR = 1.095), females (OR = 0.348), FPG (OR = 1.005), level of UA (OR = 1.517), and analgesic use (OR = 1.512) remained independent predictors of CKD. In , the median rate of eGFR decline (progression rates) calculated by simple linear regression were presented according to various subgroups of patients. Individuals that reported using analgesics showed a faster progression than those that did not use analgesics. Multivariate linear regression analysis was used to identify clinical parameters (e.g., use of analgesics, father's clan from Fujian, mother’s clan from Fujian, coffee/tea/alcohol consumption, smoking, and bet-nut use) and eGFR measurements to predict renal outcome. Use of analgesics, father’ clan from Fujian, mother’ clan from Fujian, and coffee drinking were all independent determinants of renal outcome (coefficients of regression (β) were −0.102, −0.192, 0.210, and 0.88, respectively).

Table 3. Multivariate logistic regression analysis for late-stage CKD.

Table 4. Multivariate linear regression analysis for late-stage CKD.

Educational background and use of analgesics

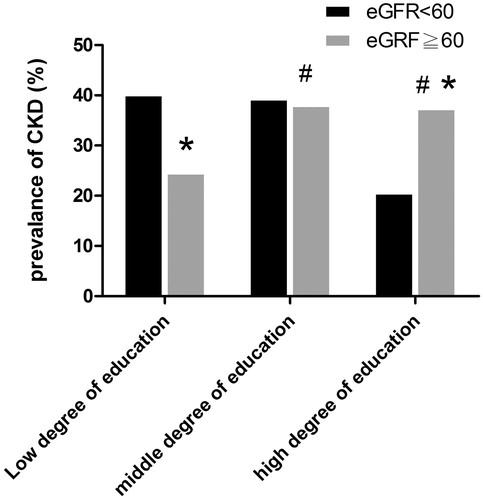

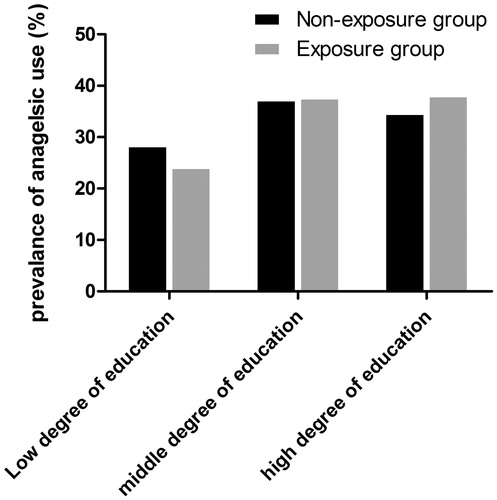

To calculate the percent of individuals with CKD in different education background tertiles, subjects were grouped based on the level of education: low degree of education (illiteracy), middle degree of education (primary and secondary schools), and high degree of education (high school, undergraduate, graduate, and PhD). As shown in , the prevalence of CKD significantly decreased with increasing education. In contrast, there was no significant difference in CKD between education background and use of analgesics ().

Discussion

This study determined that analgesic usage alone had a good ability to identify renal outcome in this population-based study performed on individuals residing in Chiayia County, Taiwan. Although previously published studies demonstrated that the use of analgesics increased the risk of renal disease, this current study adjusted for family history (i.e., genetic susceptibility and/or environmental factors) and other nonbiomedical factors (such as coffee/tea/alcohol intake, smoking, bet-nut use, and socioeconomic status) that previously were not considered in this area of research.

The results of this study provide strong epidemiologic evidence linking the use of analgesics with the development of renal disease. In fact, an overall relatively low awareness in middle-southern Taiwan was also clearly demonstrated in this study which means that the government should more pay attention to this important public issue in this area. Further, in addition to the use of analgesics, this study also clearly demonstrated that the father’s clan, mother’s clan, and intake of coffee were all independent determinants of renal outcome. Interestingly, educational background of the study participants did not seem to have any impact on the use of analgesics.

It was astonishing to the authors that there was a very low awareness on CKD in this study population despite the relatively high prevalence of aging County in Taiwan. Despite the United States’ Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's recognition of CKD as a public health concern, lack of awareness of CKD among the public, CKD's asymptomatic nature in its early stages combined with the shortage of renal care have hindered disease prevention. This lack of awareness implicates that educational intervention, especially in the rural areas of Taiwan, should be implemented as early as possible. In recognition of this theory, models of CKD care have developed over the past few decades in recognition of the fact that solitary physician visits are not adequate for increasing awareness of CKD. Patient awareness, education, and repeated interactions with various members of the health care team are integral components of care.

In this study, the authors also demonstrated that subjects with a lower degree of education group had a higher rate of CKD that was not associated with the use of analgesic. That finding suggests that it would be prudent to increase the awareness of CKD through education to abrogate the occurrence of CKD in this population. The study authors have clearly demonstrated that a multifaceted patient-centered educational intervention in the predialysis period would help retard the progression of the deterioration of renal function and to prevent the progression and/or development of the complications associated with poor renal function.Citation17 The authors of this study also suggested that there is a cost-saving effect due to early preparation of vascular access and the lack of hospitalization at dialysis initiation.Citation17 As such, the study authors routinely implement a multidisciplinary care program in the community, especially in rural areas. Of course, long-term follow-up will be required to determine whether such an intervention will increase awareness of CKD in the community and whether the people from the community who choose to modify their diet and lifestyle as a result of education can successfully increase awareness of CKD and decrease its occurrence. Further studies focusing on patient awareness in of CKD in rural areas are certainly warranted.

Although genetic linkage analyses and association studies have implicated several loci and candidate genes in the predisposition to CKD, how family history (especially from parent clan) contributes to genetic susceptibility and renal outcome from a clinical aspect remain to be identified definitively.Citation18–22 Given the ethnic differences in lifestyle and environmental factors,as well as differences in genetic background, it is important to examine genetic background related to CKD in each ethnic group. The authors of this study have now performed an association study for family background including father's clan, mother’s clan and CKD in 22,665 Taiwanese individuals. Interestingly, father's clan and mother’s clan from ancestry from Fujian (using analyzed multivariate logistic regression analysis, excluding the risk factors such as use of analgesics, coffee/tea/alcohol intake, smoking, and bet-nut use) appeared to be an important and independent predictor of renal outcome.

One previous study showed that a history of familial ESRD was reported by 14.1% of white men, 14.6% of white women, 22.9% of African-American men, and 23.9% of African-American women.Citation23 Additionally, Ferguson et al. reported that a history of CKD in a first- or second-degree relative was associated with increased risk for being a prevalent ESRD patient compared with community controls.Citation24 The same was also true in an animal model focusing on genetic background.Citation25 Both genetic susceptibility and environmental factors can interact and contribute to the development of CKD in family members; however, to the authors’ knowledge, those are important factors to consider, especially in rural areas. The observations in this study are important not only for how physicians can use easily obtainable information to alert people about the presence of the risk of renal progression in this subgroup, but also for identifying the risk factor that nephrologists can use to predict renal outcomes in the community. This study also demonstrated that tracing an individual’s genetics was practical, simple, and valuable, in contrast with other studies,Citation26,Citation27 emphasizing the importance of genotyping in the laboratory.

In this study, coffee consumption was correlated with a lower risk of CKD. That effect held even after adjusting for factors such as analgesic usage, father's clan, mother’s clan, tea/alcohol consumption, smoking, and bet-nut use. Coffee is incredibly rich in antioxidants, which are thought to be responsible for many of its health benefits. To the authors’ knowledge, cancer, diabetes and cardiovascular disease are diseases caused by inflammation, just like CKD.Citation28,Citation29 CKD is a global public health problem, and individuals with CKD are at increased risk not only for ESRD but also for a poor cardiovascular outcome and premature death.Citation30,Citation31 Previous reports have already demonstrated that coffee can help avoid diabetes, skin cancer, stress, Parkinson’s disease, breast cancer, heart disease, and head and neck cancers.Citation32–34 Pham et al. described the protective association between coffee intake and hyperuricemia,Citation35 and previously demonstrated the role of hyperuricemia in the progression of CKD. The above information therefore implies that drinking coffee would be a protective factor for CKD through anti-oxidant and anti-inflammation mechanisms.

Despite the positive findings of this study, several limitation should be mentioned. Because Community Complex Health Screening is a large-scale, free, health program for individuals ≥ 40 years of age conducted in a countywide setting by locally trained nurses, only a simple questionnaire was used to assess macroscopic indicators of life habits. The questionnaire assessed the intake of coffee according to the patients’ memory and no information was collected regarding dose of coffee consumed. Further, a cross-sectional association does not necessarily indicate causality. Therefore, further long-term prospective studies are required.

In conclusion, this population-based study found that use of analgesics was an independent risk factor for CKD in Taiwanese adults ≥ 40 years of age. The increased risk of CKD remained significant even following adjustment for sex, age, UA, cholesterol, triglyceride, and sugar. It was also found that parent’s clan from Fujian and coffee intake impacted CKD. This information emphasized the importance of genetic background and life style on the development of CKD.

Declaration of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interests. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of this article. This work was supported by grant [CMRPG6A027] from Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, Taiwan.

References

- United States Renal Data System: 2012 Annual Data Report. The National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, 2012. USRDS 2012. Available at: http://www.usrds.org/atlas.aspx. Accessed August 13, 2013

- Xue JL, Ma JZ, Louis TA, Collins AJ. Forecast of the number of patients with end-stage renal disease in the United States to the year 2010. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2001;12(12):2753–2758

- Wen CP, Cheng TYD, Tsai MK, et al. All-cause mortality attributable to chronic kidney disease: a prospective cohort study based on 462 293 adults in Taiwan. Lancet. 2008;371(9631):2173–2182

- Zeller K, Whittaker E, Sullivan L, et al. Effect of restricting dietary protein on the progression of renal failure in patients with insulin dependent diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med. 1991;324:78–84

- Sarnak MJ, Levey AS. Cardiovascular disease and chronic renal disease: a new paradigm. Am J Kidney Dis. 2000;35(4 Suppl. 1):S117–S131

- Lee PH, Chang HY, Tung CW, et al. Hypertriglyceridemia: an independent risk factor of chronic kidney disease in Taiwanese adults. Am J Med Sci. 2009;338(3):185–189

- Chang HY, Tung CW, Lee PH, et al. Hyperuricemia as an independent risk factor of chronic kidney disease in middle-aged and elderly population. Am J Med Sci. 2010;339(6):509–515

- Kuo HW, Tsai SS, Tiao MM, Yang CY. Epidemiological features of CKD in Taiwan. Am J Kidney Dis. 2007;49(1):46–55

- Yang CS, Lin CH, Chang SH, Hsu HC. Rapidly progressive fibrosing interstitial nephritis associated with Chinese herbal drugs. Am J Kidney Dis. 2000;35(2):313–318

- Kuo HW, Tsai SS, Tiao MM, et al. Analgesic use and the risk for progression of chronic kidney disease. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2010;19(7):745–751

- Jurkovitz C, Franch H, Shoham D, Bellenger J, McClellan W. Family members of patients treated for ESRD have high rates of undetected kidney disease. Am J Kidney Dis. 2002;40:1173–1178

- Norris K, Nissenson AR. Race, gender, and socioeconomic disparities in CKD in the United States. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;19(7):1261–1270

- Pham PC, Dewar K, Hashmi S, et al. Pain prevalence in patients with chronic kidney disease. Clin Nephrol. 2010;73(4):294–299

- Kuo HW, Tsai SS, Tiao MM, Liu YC, Lee IM, Yang CY. Analgesic use and the risk for progression of chronic kidney disease. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2010;19(7):745–751

- Freedman BI, Soucie JM, Kenderes B, et al. Family history of end-stage renal disease does not predict dialytic survival. Am J Kidney Dis. 2001;38:547–552

- National Kidney Foundation. K/DOQI clinical practice guidelines for chronic kidney disease: evaluation, classification, and stratification. Am J Kidney Dis. 2002;39:S1–S246

- Lei CC, Lee PH, Hsu YC, et al. Educational intervention in CKD retards disease progression and reduces medical costs for patients with stage 5 CKD. Ren Fail. 2013;35(1):9–16

- Gharavi AG, Yan Y, Scolari F, et al. IgA nephropathy, the most common cause of glomerulonephritis, is linked to 6q22–23. Nat Genet. 2000;26:354–357

- Hanson RL, Craig DW, Millis MP, et al. Identification of PVT1 as a candidate gene for end-stage renal disease in type 2 diabetes using a pooling-based genome-wide single nucleotide polymorphism association study. Diabetes. 2007;56:975–983

- Födinger M, Veitl M, Skoupy S, et al. Effect of TCN2 776C>G on vitamin B12 cellular availability in end-stage renal disease patients. Kidney Int. 2003;64:1095–1100

- Wetmore JB, Hung AM, Lovett DH, et al. Interleukin-1 gene cluster polymorphisms predict risk of ESRD. Kidney Int. 2005;68:278–284

- Doi K, Noiri E, Nakao A, et al. Functional polymorphisms in the vascular endothelial growth factor gene are associated with development of end-stage renal disease in males. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17:823–830

- Freedman BI, Soucie JM, Kenderes B, et al. Family history of end-stage renal disease does not predict dialytic survival. Am J Kidney Dis. 2001;38:547–552

- Ferguson R, Grim CE, Opgenorth TJ. A familial risk of chronic renal failure among blacks on dialysis? J Clin Epidemiol. 1988;41:1189–1196

- Puri TS, Shakaib MI, Chang A. Chronic kidney disease induced in mice by reversible unilateral ureteral obstruction is dependent on genetic background. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2010;298(4):F1024–F1032

- Yoshida T, Kato K, Fujimaki T. Association of genetic variants with chronic kidney disease in Japanese individuals. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;4:883–890

- Datta SK, Kumar V, Pathak R, et al. Association of glutathione S-transferase M1 and T1 gene polymorphism with oxidative stress in diabetic and nondiabetic chronic kidney disease. Ren Fail. 2010;32(10):1189–1195

- Ma S, Richardson JA, Bitmansour A, et al. Partial depletion of regulatory T cells does not influence the inflammation caused by high dose hemi-body irradiation. PLoS One. 2013;8(2):e56607

- Herzlinger S, Horton ES. Extraglycemic effects of glp-1-based therapeutics: addressing metabolic and cardiovascular risks associated with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2013;100(1):1–10

- Khunti K, Morris DH, Weston CL, et al. Joint prevalence of diabetes, impaired glucose regulation, cardiovascular disease risk and chronic kidney disease in South Asians and White Europeans. PLoS One. 2013;8(1):e55580

- Frimodt-Møller M, Kamper AL, Strandgaard S, Kreiner S, Nielsen AH. Beneficial effects on arterial stiffness and pulse-wave reflection of combined enalapril and candesartan in chronic kidney disease–a randomized trial. PLoS One. 2012;7(7):e41757

- Song F, Qureshi AA, Han J. Increased caffeine intake is associated with reduced risk of basal cell carcinoma of the skin. Cancer Res. 2012;72(13):3282–3289

- Cano-Marquina A, Tarín JJ, Cano A. The impact of coffee on health. Maturitas. 2013;75(1):7–21

- Freedman ND, Park Y, Abnet CC, Hollenbeck AR, Sinha R. Association of coffee drinking with total and cause-specific mortality. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(20):1891–1904

- Pham NM, Yoshida D, Morita M, et al. The relation of coffee consumption to serum uric Acid in Japanese men and women aged 49-76 years. J Nutr Metab. 2010; 2010:930757. doi: 10.1155/2010/930757