Abstract

Nonprescription medications are relatively safe, but not risk-free and can lead to serious adverse events, particularly if used contrary to directions or without attention to depicted warnings. The question arises whether the information presented on the product label is readable and comprehensible to the average lay person. We examined the product labels of nonprescription medications for readability and comprehensibility characteristics using the Flesch–Kincaid method. The Flesch–Kincaid reading ease scores and grade level scores were derived. We further validated the grade level scores using the Gunning–Fog method. Qualitative assessment of select labels found severe deficiencies such as poor organization and inundation with technical terms. By quantitative assessment the average reading ease score of 40 nonprescription medication labels (including nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents, antacids, laxative preparations, anti-allergy medications, H-2 blockers, proton pump inhibitors, sleep aids, an antiasthmatic, and cough and cold remedies) was 38 ± 12. The average Flesch–Kincaid grade level score was 16 ± 5. All labels except one were at reading grade level greater than the eighth grade. The average grade level of education necessary to understand the material according to the Gunning–Fog method was 17 ± 5 and all labels were above the eighth grade reading level. Nonprescription medication labels are written in a language that is not comprehensible to the average member of the general public. There is a need for considerable improvement in the readability of these labels.

Introduction

Several medications are available without the prescription of a licensed medical practitioner. The list of such nonprescription drugs, commonly known as over-the-counter (OTC) agents, has recently expanded as more agents have safety data accrued over time. The nonprescription drug market is significant in magnitude with sales in year 2010 equaling $23 billion.Citation1

It is important to recognize nonprescription medications are relatively safe, but not risk-free. Serious risks are well known, even related to products that have been in the market for a period of time, such as gastrointestinal bleeding associated with nonsteroidal agents. We continually become aware of new risks of pharmaceuticals and nonprescription medications are no exceptions in this regard. Cardiovascular risks associated with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and hypomagnesemia associated with proton-pump inhibitors are examples of recently recognized risks of some OTC agents.

As representative examples of risks associated with nonprescription agents we observed life-threatening hypermagnesemia due to excessive use of antacids by a 76-year-old woman living in a group home, in which case serum magnesium reached 15 mg/dL and the patient nearly died. In another case, hyperkalemia and acute kidney injury occurred related to ibuprofen use by a 77-year-old man with chronic kidney disease living alone in an apartment. It is apparent these examples represent prototypical examples of elderly individuals at risk of drug side effects. One of the patients, when asked whether he had read the ibuprofen label since the label does state to ask a doctor before use if the person has kidney disease, replied in the negative indicating it was hard to read.

Each nonprescription drug product is required to bear a label, depicting purposes, uses, and warnings, governed by Title 21 Code of Federal Regulations part 201 subpart C.Citation2 The label is the only safeguard against improper use, since such agents can be bought off the shelves and taken without medical supervision or direction. Instances such as depicted above raise the important issue whether the product labels are readable and comprehensible to the average lay member of the public. We examined nonprescription drug labels for readability and other characteristics.

Methods

We examined the readability and comprehensibility of a wide range of nonprescription medication labels using the Flesch–Kincaid method.Citation3 The method provides a reading ease score and reading grade level score for textual material. A higher reading ease score implies the text is proportionately easier to read and the grade level score refers to the grade level required to have entered to understand the material. The Flesch–Kincaid method is the most commonly used and tested readability instrument and is widely considered suitable for all kinds of text including health care text.Citation4 The method has a correlation of 0.91 with grade level understanding in reading tests and has been used extensively to assess readability of health care literature.Citation5–12 The method is also used to determine readability of written materials for employees and the public by various institutions. For example, the State of Florida mandates that all insurance policies must have a minimum Flesch–Kincaid reading ease score of 45.13 Each readability score was derived twice for verification and rounded to the whole integer.14 Finally, we determined the grade level of education required to comprehend the labels using the Gunning–Fog method, which is another less commonly used method employed to assess readability of health care material.9–11

Results

Forty nonprescription medications were evaluated. These included nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents, antacids, laxative preparations, anti-allergy medications, H-2 blockers, proton pump inhibitors, sleep aids, an antiasthmatic, and cough and cold remedies. The average reading ease score of the nonprescription labels was 38 ± 12 and average grade level required to understand the material was 16 ± 5 (). None of the labels except one were at eighth reading grade level and none at a reading grade level less than the eighth grade. The average grade level of education required to comprehend the labels according to Gunning–Fog method was one grade higher at 17 ± 5 and all the labels were at a reading grade level greater than eighth grade. Nonsteroidal labels were among the worst performers having a reading ease score of 24 ± 9 and a Flesch–Kincaid grade level of 22 ± 3.

Table 1. Reading ease and grade level scores of over-the-counter labels.

To put these metrics in context, magazines such as Reader's Digest and Time have reading ease scores more than 50 and the Harvard Law Review is said to have a general reading ease score in the low 30s.15

Besides these objective poor readability characteristics, there were several deficiencies apparent on a common sense viewpoint exemplified by an ibuprofen label (vide infra). In many instances, the amount of small print information inserted in limited space made it quite difficult to follow, even for us. Of note, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) allows font size as small as 6 for information described under headings such as “Uses”, and “Warnings”, “Stop use and ask a doctor if”.Citation2,16 Not all labels ask the consumer to read the entire material, or even the important material, before use.

Ibuprofen label

An ibuprofen product label we examined suffers from abundant small-print information distributed on five sides of the product box. The fact that is useful to obtain relief for pain and fever is prominently depicted, in large print, on one face of the box. However, the presentation of other important information leaves much to be desired. For example, a long list of warnings are included in one subsection, not to use situations in another, to consult a physician before use in a third, ask a doctor or pharmacist before use in a fourth, and how to take it advice comingled with a warning/risk in a fifth subsection on a side of the product box about 2.75″ × 1.75″ in size. There are about 220 words in this space. On another side, there are additional small print warnings/advices such as when to stop using and ask a doctor, directions, and so on. Moreover, the content is filled with technical terms. The language includes terms like “NSAID”, refers to concurrent “diuretic” use or presence of “liver cirrhosis” among reasons “to ask a doctor before use”.

Discussion

Our results show that nonprescription medication labels, which bear important information about directions, risks and warnings, are written in a language with poor readability and comprehensibility characteristics. On an average, the readability is worse than certain news and informational magazines and requires college undergraduate level of education to comprehend the material.

Certain high risk group of OTC agents fared particularly poorly. We consider NSAIDs as among the most risk-associated nonprescription medications, with potential adverse reactions ranging from gastrointestinal bleeding, renal injury, exacerbation of hypertension, potential for hyperkalemia, and more recently identified cardiovascular risks. NSAID labels had an average reading ease score of 24 and grade level score of 22. In other words, the readability is worse than that of Harvard Law Review and requires graduate level education to understand the material.

It is relevant to consider health care material in the context of the comprehensibility of the US general population. The National Adult Literacy Survey revealed that about a quarter of the adult US population could not read or understand written materials below a fifth grade level.17,18 There has not been a significant change in the average document literacy of US adults through the early twenty-first century as compared to the early 1990s.19 The average US reading ability is considered equivalent to the eighth grade level.20 Furthermore, data have shown that low literacy corresponds with a poor ability to understand instructions on prescription drug bottles, poor comprehension of health care risks, and low self-care abilities.18,21 These points are pertinent related to use of nonprescription medications.

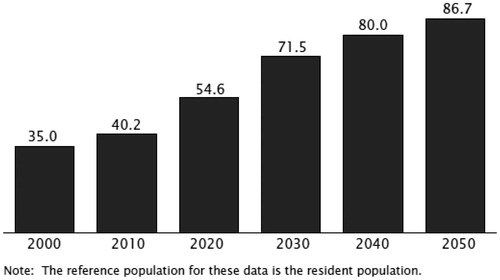

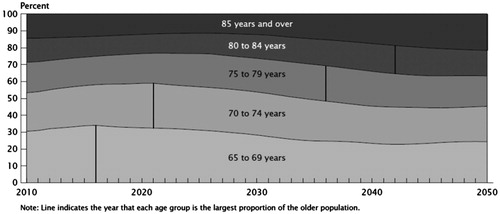

There is another critical issue related to this matter. The health care community is facing an aging population, a group particularly vulnerable to drug side effects. A report released by the US Census Bureau on November 30, 2011 showed that the U.S. population 65 and older is now the largest in terms of size and percent of the population.22 Between 2000 and 2010, the 65 and older population had the second fastest growth rate among various age groups (a growth rate of 15.1% to a total number 40.3 million).23 The fastest growth rate of 31.5% was observed in the 45- to 64-year age group due to baby boomers entering this age range. In the near future the latter group will transition into the 65 and older group such that by 2030 nearly one in five people will be 65 years old or older. shows the growth in numbers of the older age group.24 Further, as shown in progressively older individuals will constitute the majority among the elderly.25 For instance, in less than 10 years from now the majority of senior individuals will be between 70 and 74 years old. In elderly individuals, the function of pathways for drug inactivation and elimination may be diminished. Further, the elderly who may have impaired sensory pathways and subtle often undetected cognitive impairment may be more prone to self-medication errors. Such patients probably face greater challenges in reading the small font and understanding the complexity of the terms often used in nonprescription product labels.26 Moreover, these individuals are more likely to need medications and represent 30% of the nonprescription consumer market.26

We reviewed Title 21 Code of Federal Regulations part 201 subpart C, which govern OTC medication labeling requirements.Citation2 The regulations contain no specific readability or grade level criteria for nonprescription labels. The rulemaking history suggests no recent major changes in the labeling regulations.27 Substantive changes in labeling requirements were published in March 1999, specifically the requirement of a Drug Facts Label with a compliance deadline for most OTC drug products of May 2002.26 The FDA conducted extensive research to understand how consumers use OTC drug products labels and used the findings to draft the regulations. Among the goals of the “Drug Facts” label was for the OTC label to include easier to understand terms and thus required the word “indications” to be replaced by “uses” and words like “precautions” and “contraindication” to be replaced by simpler terms. However, our review shows labels continue to include terms like “diuretic” and “cirrhosis”, which are arguably more difficult to understand than “precautions”.

In August 2010, the FDA published a guidance document for the industry regarding label comprehension studies for nonprescription drug products.27 The document, which “Contains Nonbinding Recommendations”, recognizes that the average grade level in the United States is estimated to be eighth grade and that standard practice is to write medical information at a fourth to fifth grade level. It recommends that attempts should be made to write the nonprescription label at a fourth to fifth grade level and no higher than eighth grade level. The guidance document makes it clear that it does not establish legally enforceable responsibilities and the use of the word should means that something is suggested or recommended but not required. Our analysis shows that most current nonprescription labels are at a much higher reading grade level than the FDA’s suggested guidance.

The authors have several recommendations. Firstly, there should be specific readability and grade level criteria for OTC medication labeling using a validated instrument such as the Flesch–Kincaid method. Important information should be consolidated into a lesser number of headings, for example one describing directions and other describing negative aspects. Side effects, warnings, and precautions should be displaced in a font that is more prominent than that displays uses via capitalization, bolding, or other such manner. Every label should bear a large font, bolded and capitalized phrase, prominently placed below the name, alerting the prospective user to read the entire label (or material under important headings) before use. Finally, label comprehension studies should be mandatory.

There is no question that nonprescription medications serve a very useful function. For consumers they provide easy access to treatment for minor ailments. For the health care industry they obviate the need for interaction with the consumer for non-serious situations and help preserve resources. Regulation of nonprescription agents is a vexing problem given the myriad of agents, a broad array of possible adverse effects, and differences in consumer mix and behavior. We recognize that providing directions in a manner that is readable and understandable does not imply end users will follow the directives. But it is a necessary first step. Also, it is unlikely that every nonprescription drug-related adverse event will be prevented. But we need to do better.

In conclusion, most nonprescription drug labels that bear important information for consumers are written in a manner that is beyond comprehension of an average lay member of the public. Given anticipated future population demographics, unless pro-active steps are taken, adverse events related to nonprescription drugs some of which may be life-threatening will probably rise over the ensuing years.

Declaration of interest

Hariprasad Trivedi has the following relationship with commercial interests: Abbott Laboratories – Advisory Board; Genzyme Corporation – investigator-initiated grant recipient; research talk with compensation; Covidien – research contract with institution, site principle investigator; Amgen- research contract with institution, co-investigator. Akshaya Trivedi – no personal conflict of interest but son of Hariprasad Trivedi. Mary Hannan – no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Charlotte Klis for secretarial support and Mihir Trivedi for his effort in calculation of the readability statistics.

References

- The value of OTC medicine to the United States. Available at: http://www.yourhealthathand.org/images/uploads/The_Value_of_OTC_Medicine_to_the_United_States_BoozCo.pdf. Accessed December 21, 2012

- CFR – Code of Federal Regulations Title 21. Available at: http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfCFR/CFRSearch.cfm?CFRPart=201&showFR=1&subpartNode=21:4.0.1.1.2.3. Accessed May 9, 2013

- Kincaid JP, Fishburne RP, Rogers RL, Chissom BS. Derivation of new readability formulas (Automated Readability Index, Fog Count, and Flesch Reading Ease formula) for navy enlisted personnel. Chief of Naval Technical Training: Naval Air Station Memphis. Research branch report; 1975:8–75

- Dawson J. How to choose the best readability formula for your document. Available at: http://jessedawson.articlealley.com/how-to-choose-the-best-readability-formula-for-your-document-753014.html. Accessed December 19, 2012

- DuBay WH. Smart Language-Readers, Readability, and the Grading of Text. Costa Mesa, CA: Impact Information; 2007. ISBN: 1‐4196‐5439‐X. Available at: http://www.impact-information.com/impactinfo/newsletter/smartlanguage02.pdf. Accessed December 15, 2012

- Williamson JM, Martin AG. Analysis of patient information leaflets provided by a district general hospital by the Flesch and Flesch–Kincaid method. Int J Clin Pract. 2010;64:1824–1831

- Pothier L, Day R, Harris C, Pothier DD. Readability statistics of patient information leaflets in a Speech and Language Therapy Department. Int J Lang Commun Disord. 2008;43:712–722

- Harwood A, Harrison JE. How readable are orthodontic patient information leaflets? J Orthod. 2004;31:210–219

- Murphy J, Gamble G, Sharpe N. Readability of subject information leaflets for medical research. N Z Med J. 1994;107:509–510

- Grossman SA, Piantadosi S, Covahey C. Are informed consent forms that describe clinical oncology research protocols readable by most patients and their families? J Clin Oncol. 1994;12:2211–2215

- Sharp SM. Consent documents for oncology trials: does anybody read these things? Am J Clin Oncol. 2004;27:570–575

- Paasche-Orlow MK, Taylor HA, Brancati FL. Readability standards for informed consent forms as compared with actual readability. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:721–726

- The 2012 Florida Statues. Title XXXVII, Chapter 627, Part II; 627.4145, 1a. Available at: http://www.leg.state.fl.us/statutes/. Accessed December 15, 2012

- Readability-score.com. Available at: http://www.readability-score.com/. Accessed December 13, 2012

- Clear language. Workplace Education Manitoba, Winnipeg, Manitoba. Available at: http://www.nald.ca/library/research/clear/5.htm. Accessed December 15, 2012

- Ingersoll B, Rooney PC. OTC labeling requirements. Available at: http://corporate.findlaw.com/law-library/otc-labeling-requirements.html. Accessed December 15, 2012

- Kirsch IS, Jungeblut A, Jenkins L, Kolstad A. Adult literacy in America: a first look at the findings of the National Adult Literacy Survey. Washington DC: National Center for Education Statistics, U.S. Department of Education; 1993. Available at: http://nces.ed.gov/pubs93/93275.pdf. Accessed September 10, 2013

- Liu E, Lo T-F, Hsieh H-L. Literacy and health: evidence from the National Assessment of Adult Literacy. IJAE. 2011;8:17–35

- Kunter M, Greenberg E, Baer J. A first look at the literacy of America’s adults in the 21st century. Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics, U.S. Department of Education; 2005. Available at: http://nces.ed.gov/naal/pdf/2006470.pdf. Accessed September 10, 2013

- Cotunga N, Vickery CE, Carpenter-Haefele KM. Evaluation of literacy level of patient education pages in health-related journals. J Community Health. 2005;30:213–219

- Williams MV, Baker DW, Honig EG, Lee TM, Nowlan A. Inadequate literacy is a barrier to asthma knowledge and self-care. Chest. 1998;114:1008–1015

- United States Census Bureau. Census shows 65 and older population growing faster than total U.S. population; 2010. Available at: http://www.census.gov/newsroom/releases/archives/2010_census/cb11-cn192.html. Accessed December 19, 2012

- Howden LM, Meyer JA. Age and sex composition: 2010; 2010 Census briefs. Available at: http://www.census.gov/prod/cen2010/briefs/c2010br-03.pdf. Accessed December 19, 2012

- He W, Sengupta M, Velkoff VA, DeBarros KA. Current population reports: special studies. 65 + in the United States; 2005. Available at: http://www.census.gov/prod/2006pubs/p23-209.pdf. Accessed December 19, 2012

- Vincent GK, Velkoff VA. Current population reports. The next four decades. The older population in the United States: 2010 to 2050. Available at: http://www.census.gov/prod/2010pubs/p25-1138.pdf. Accessed December 19, 2012

- OTC Drug Facts Label. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/ResourcesForYou/Consumers/ucm143551.htm. Accessed December 19, 2012

- Rulemaking history of general labeling requirements for OTC drug products. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DevelopmentApprovalProcess/DevelopmentResources/Over-the-CounterOTCDrugs/StatusofOTCRulemakings/ucm071365.htm. Accessed January 17, 2013