Abstract

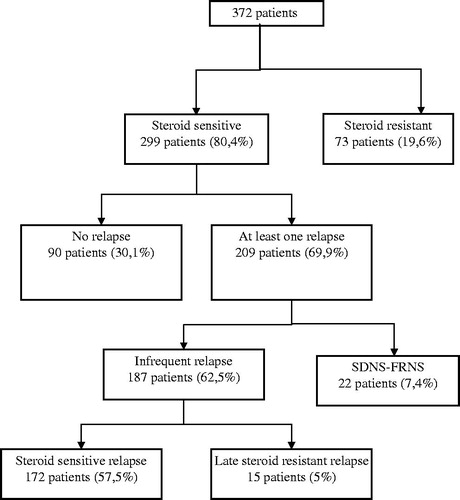

Background: To investigate the demographic, clinical and laboratory data of the children with idiopathic nephrotic syndrome (INS), and to determine prognostic factors that affect the clinical outcome of the patients. Methods: Medical charts of 372 patients diagnosed to have INS and followed up at least 5 years between January 1990 and December 2008 were evaluated, respectively. After initial demographic, clinical and laboratory findings of the patients were documented, therapeutic protocols, prognosis and prognostic factors were investigated. Results: 299 of the patients (80.4%) were steroid responsive and 73 (19.6%) were not. Focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS) was observed in 57%, minimal change disease (MCD) in 20.6% and diffuse mesengial proliferation in 21.9% renal biopsy materials. Steroid sensitivity was higher in patients with MCD and under the age of five years. Resistance to steroids was higher in children with FSGS. Complete remission was achieved in 96% of patients who were sensitive to steroids and in 46.6% who were resistant. 15% of patients who were steroid resistant developed chronic kidney disease (CKD). Conclusion: Intercurrent infections and response to steroid therapy are the most important factors affecting the prognosis of the disease.

Introduction

Idiopathic nephrotic syndrome (INS) is a common glomerular disorder in childhood characterized by heavy proteinuria, hypoalbuminemia, edema and hyperlipidemia and 70–80% of cases occur in children less than six years of age.Citation1 The best predictor of prognosis of the disease is the response to steroid therapy and the children that failed to have complete remission following the initial corticosteroid treatment are at higher risk for potential development of progressive renal disease. Although the mortality of the disease decreased to less than 5% after the development of antibiotics and corticosteroids; infections, relapses and the adverse effects of therapeutic agents are still important causes of mortality and morbidity in INS. Thus, the management and follow up of patients cause therapeutic dilemma for pediatric nephrologists from time to time and it is important to know the long-term prognosis of the patients. However, there is no adequate number of published clinical studies demonstrating the experience of different centers and pediatric nephrologists about the clinical spectrum and long term outcome of INS in recent years.

In this study, we aimed to investigate the demographic, clinical and laboratory data of the children with INS, and to determine the therapeutic difficulties, prognosis and prognostic factors that affect the clinical outcome of the patients.

Materials and methods

The children diagnosed to have INS between January 1990 and December 2008 and followed up at least 5 years were included in this retrospective study. After initial demographic, clinical and laboratory findings of the patients were documented, therapeutic protocols, prognosis and prognostic factors were investigated.

The patients with massive proteinuria (>40 mg/m2/h or 960 mg/m2/day) and hypoalbuminemia (<2.5 gr/dL) were defined to have nephrotic syndrome (NS). Patients between 1 and 11 years of age with good response to steroid treatment and without any findings suggesting secondary causes of nephrotic syndrome, or patients with histologic diagnosis of minimal change disease (MCD), mesangial proliferation (MP) and focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS) were accepted to have INS.

Percutaneous renal needle biopsy was performed on all patients below 12 months of age and over 11 years; on patients presented with macroscopic hematuria, persistent hypertension, renal failure, hypocomplementemia and suggestive findings of a secondary cause and on patients resistant to steroid therapy. Patients with secondary nephrotic syndrome and with histopathological findings other than MCD, MP and FSGS were excluded from the study.

Definitions

Remission: reduction of proteinuria to <4 mg/m2/h or urine albumin dipstick of negative or trace for three consecutive days.

Relapse: recurrence of massive proteinuria to >40 mg/m2/h or urine albumin dipstick ≥2+ for three consecutive days.

Steroid sensitive NS (SSNS): achieving remission with steroid therapy alone in 4–8 weeks.

Steroid resistant NS (SRNS): failing to achieve remission after 8 weeks of steroid therapy.

Steroid dependent NS (SDNS): developing relapses either during the steroid therapy at tapering doses, or within 2 weeks of discontinuation of treatment.

Frequent relapsing NS (FRNS): developing four or more relapses during a period of 12 months or two or more relapses in 6 months time.

Late steroid resistance (LSR): failing to enter remission with steroid during relapses in patients with initial SSNS.

Partial remission (PR): improvement of serum albumin levels to normal levels despite persistent proteinuria.

Spontan remission (SR): development of remission before initiation of immunosuppressive therapy.

All the patients with INS were initially given daily oral prednisolone at a dose of 60 mg/m2/day (maximum 60 mg) for 4–8 weeks and at a tapering alternate day doses for 10 weeks. Relapsing patients were treated with same doses but with a shorter duration. Different immunosuppressive agents were started to patients with SRNS, SDNS and FRNS. Cyclophosphamide was given at a dose of 2 mg/kg/day for 8–12 weeks, chlorambucil 0.2 mg/kg/day for 8–12 weeks, cyclosporine A 3–5 mg/kg/day for 6–12 months and mycophenolate mophetil 1200 mg/m2/day together with low dose prednisolone (10 mg/m2/day). Tune–Mendosa protocol was applied to the patients with SRNS who were unresponsive to these agents ().

Table 1. Tune–Mendosa protocol.

The patients were divided into two groups according to their ages as Group 1: 5 years and below; Group 2: above 5 years. These two groups were compared with each other according to the sex distribution, presence of hematuria, hypertension, biopsy findings, response to steroid therapy and frequency of relapses. In addition, the patients with hematuria and/or hypertension at first presentation were compared to patients without these findings for their response to steroid therapy and histopathological findings. Biopsy findings and prognosis were also compared between the patients with SSNS, SRNS, SDNS and/or FRNS. Moreover, the patients that received albumin infusions as supportive therapy at initial attack were compared to the patients who did not receive albumin in regard to frequency of relapses.

Statistical analyses

Mann–Whitney U test, Chi-square test and Fisher’s Exact test were used for statistical analyses and p-values below 0.05 (p < 0.05) were accepted to be significant.

Results

During a period of 19 years, 392 patients (236 boys, 156 girls) were diagnosed to have INS. Eighty percent (314 patients) of them were at their initial attacks. Their ages were between 7 months and 18 years with a mean age of 4.74 ± 3.4 years. After 20 patients were excluded from the study (six because of spontanea remission and 14 for lost to follow up after initial work up), 372 patients were started on steroid therapy.

The most common clinical findings at presentation were edema (99.5%), fever (50.8%), cough (47.9%) and nausea and vomiting (19.2%). Five patients had a positive family history for NS. Findings of infection were present in 59.2% of the patients and respiratory and urinary tracts were the most common sites of infection ().

Table 2. Clinical and laboratory findings of patients at first presentation.

As shown in , 80.4% of the patients responded to steroid therapy while 19.6% did not. The mean follow-up period of these patients was 8.5 years with a total period of 38/138 patient months. Fifteen patients developed LSR.

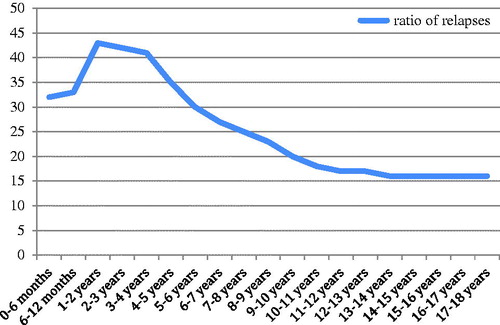

Of the patients with SSNS, 209 patients (69.9%) suffered from at least one relapse while 90 (30.1%) had no relapse. Relapsing patients developed a total of 331 relapses and the relapse rate was found to be 1/115 patient months. Most of the relapses (44.4%) were associated with infections particularly respiratory and urinary tract infections. Relapses were mostly occurred in the first year after diagnosis. Twenty-two patients were found to have FRNS and 11 of them were accepted to be SDNS.

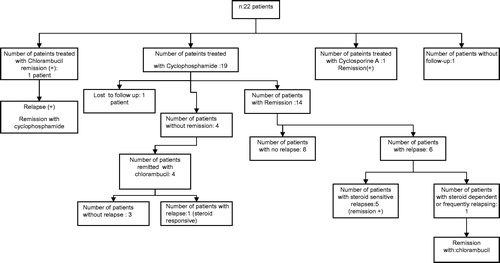

Two patients with FRNS and/or SDNS were lost to follow-up. Fourteen patients achieved remission with cyclophosphamide, five patients with chlorambucil and one with cyclosporine A. Six patients treated with cyclophosphamide developed relapses during follow-up period and one of them had FRNS/SDNS again and remitted with chlorambucil ().

Figure 2. Response to immunosupressive treatments in children with steroid dependent or frequently relapsing nephrotic syndrome.

Renal biopsy was performed on 73 patients (19.6%), with SRNS, SDNS and/or FRNS. FSGS was observed in 42 (57.5%), DMP in 16 (22.5%) and MCD in 15 (20.6%) of the biopsy materials. MCD was the most common biopsy finding (43.7%) among SSNS and FSGS was the most common (70.6 %) among SRNS and this was statistically significant (p < 0.05) (). When the patients were compared for renal biopsy findings, response to steroid treatment, rate of relapses, hematuria and hypertension according to gender, hematuria was found to be more common in girls (p < 0.05) and relapses were more common in boys but this difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.68). There were no significant differences between sexes in regard to other parameters (p > 0.05, ).

Table 3. Renal biopsy findings of patients according to steroid response.

Table 4. Clinical findings and prognosis according to gender.

When the age groups were compared to each other according to the response to steroid therapy, steroid sensitivity and frequency of relapses were significantly higher in Group 1 and resistance to steroids was significantly higher in Group 2 (p < 0.05). There were no significant differences among other parameters including sex distribution, presence of hematuria and hypertension, and histopathological findings, between the two groups (p > 0.05) ().

Table 5. Clinical findings and prognosis according to age groups.

Patients who had hypertension and hematuria at admission were more frequently resistant to steroids and FSGS was more common on their biopsy specimens. Twenty-four of 45 patients (53.4%) who were hypertensive at admission were resistant to steroids and 21 of 45 (46.6%) were sensitive. Resistance to steroids was significantly higher among patients with hypertension (p = 0.001). Twenty patients (44.4%) underwent renal biopsy among hypertensive patients and 18 of them (90%) were diagnosed as FSGS and two (10 %) as DMP. FSGS was the most common histopathological finding among patients with hypertension and this was statistically significant (p = 0.001). Among 103 patients who had hematuria at admission 37 were steroid resistant and 66 were steroid sensitive and steroid resistance was significantly higher among patients with hematuria (p = 0.001). Thirty-three of 103 (30.8%) patients with hematuria underwent renal biopsy. FSGS was detected in 21, DMP in 7 and MCD in 5 of them. FSGS was the most common histopathological finding among patients with hematuria and this relation was statistically significant (p = 0.001).

There was no statistically significant difference in regard to frequency of relapses between patients who received albumin and who did not (p > 0.5).

However, the relapse rate was significantly higher in patients with infection-related relapses than the patients without infection (p = 0.001).

Relapses were most frequently observed in the first year of the disease and relapse rate decreased within time after the first year ().

As shown in complete remission was achieved in 96.7% of patients with SSNS and 91% of SDNS and/or FRNS patients and none of them developed chronic kidney disease (CKD) or end stage renal disease. One patient died because of peritonitis among SSNS patients (0.4%). Among SRNS patients complete remission was achieved in 46.6%, partial remission in 11%; 11% of patients developed CKD and 4.1% developed ESRD and two of the patients (2.7%) died (one because of cerebrovascular accident and one because of peritonitis during CAPD). Complete remission was observed in 80% of patients with LSR and one of them (6.7%) developed ESRD.

Table 6. Prognosis according to response to steroids.

Discussion

INS is the most frequent cause of NS in children and predominantly includes three histopathological subtypes, MCNS, FSGS and DMP.Citation2 Resistance to steroid treatment and intercurrent infections are the main causes of morbidity and mortality in children with INS.Citation3

In early childhood, INS is two times more frequent in boys than in girls, but this balance is disrupted in adolescence affecting both girls and boys equally. Mekahli et al.Citation4 found the ratio between boys and girls to be 1.4/1 and it was 1.5/1 in our study. The age of disease onset is usually towards two years; and the majority of the children are under the age of 6 years. In the study of Bircan et al.Citation5 the mean age of the 138 children evaluated was found to be 4.9 years. In concordance with this report the mean age of the children in our study was 4.7 and 69.4% of the patients were under the age of five years.

In a previous study from our country steroid response was reported to be 87%.Citation5 In the Nigerian studyCitation6 this rate was only 22% while in Saudi Arabian trial it was as high as 84%.Citation7 Among our patients 80.4% were initially responsive to steroid treatment and 19.6% were unresponsive.

Ninety patients (30.1%) did not have any relapses during the follow-up period whereas 209 (69.9%) of them had at least one relapse. Among relapsing patients 22 (7.5%) were steroid dependent and/or frequent relapser. Relapse rate was 1/115 patient months. Relapses were mostly seen within the first year of the disease onset and then decreased over time. One hundred and fourty-seven of the relapses (44.4%) were associated with infections. Infectious episodes in nephrotic patients are responsible for high morbidity leading to recurrences among patients in remission and inadequate response to corticosteroid therapy.Citation8 According to Yap et al.,Citation9 frequent relapses and steroid dependence were found significantly higher in children who had upper respiratory tract infection and responded to initial steroid therapy after nine days. In concordance with these studies, in our study, relapse rate was higher in children whose relapses were associated with infection (p = 0.001). Because infections are the most important triggers for relapses in nephrotic syndrome, primary immunization should be completed in these children.Citation10 Patients who receive prednisolone at a dose of 2 mg/kg/day or total 20 mg/day (for patients over 10 kg) or greater for more than 14 days are defined as immunocompromised.Citation11 Live attenuated vaccines cannot be provided for these patients but inactivated or killed vaccines are safe.Citation11 Peritonitis is also a common infection in children with nephrotic syndrome and streptococcus pneumonia is the major cause of peritonitis so all children with nephrotic syndrome should receive immunization against pneumococcal infections.Citation12

Age of the patient is also important for the frequency of relapses. We observed that higher frequency of relapses was seen in children less than 5 years. Some studies also indicate that younger age at onset predicts a higher likelihood of continuing to relapse in adult life.Citation13,Citation14

Recent studies indicate that extending initial attack treatment with steroids to 12 weeks or continuing low dose steroids to 18 months decrease the rate of relapses.Citation15,Citation16 We used steroids for 14 weeks at the first attack and we did not observe severe side effects and the relapse rate was 69.9%. This rate was 32.1% in the study of Davutoğlu et al.Citation17 We attributed the high relapse rate in our study to the long-term follow-up of our patients.

ISKDC reported almost 30 years ago that MCNS was presented in 77% of all renal biopsies performed in children with idiopathic nephrotic syndrome. In this study, FSGS was detected in 10%, DMP in 3% and other forms of glomerulonephritis were detected in 10% of renal biopsy specimens.Citation2 Like these observations MCNS formed 88% of biopsies in the study of White et al.Citation18 Ejaz et al. performed renal biopsies in children who had SDNS, SRNS and FRNS and they found out that FSGS formed 42% and MCNS 22% of renal biopsy specimens.Citation19 We also performed renal biopsies in 73 children who were either SDNS, SRNS or FRNS. Fifteen (20.6%) of them had MCNS, 42 (57.5%) had FSGS and 16 (21.9 %) had DMP. MCNS and DMP were in similar frequency and FSGS was obviously higher than other histopathological forms. This observation can be attributed to the fact that we had performed biopsies in a selected group of patients who responded poorly to steroid treatment. Also this observation may be related to the increasing frequency of FSGS as indicated in the study of Bonilla-Felix et al.Citation20

In previous studies, the incidence of hematuria has been reported to be higher in patients with steroid resistance.Citation21,Citation22 Banaszak and BanaszakCitation23 detected that the frequency of microscopic hematuria significantly increased with the increased rate of steroid resistance frequency. In concordance with these studies microscopic hematuria was observed in 33.3% of children with MCNS and 50% of FSGS who were resistant to steroids.

Hypertension is rare in patients with MCNS and may only be detected in a ratio of 6–13% at the beginning of the disease course.Citation24 Relapses and resistance to steroids were observed in 75% of patients with hypertension in the study of Davutoğlu et al.Citation17 We also observed that hypertension was more frequent among the patients who are non-responsive to steroid therapy (32.8%). FSGS was more common in children who were hypertensive and who had microscopic hematuria at first visit and this was statistically significant (p < 0.05).

Steroid sensitivity was reported in 89% of children with INS.Citation19 In the study of ISKDC the response to steroids was found to be 78.1 among patients with MCD, 29.7% in FSGS and 55% in DMP, respectively.Citation25 In our study, 80.4% of patients responded to steroids. 14.3% of patients with FSGS, 43.7% of DMP and 60.2% of patients with MCD were responsive to steroid therapy, respectively. The relatively low rate of steroid response among children with MCD in our study can be attributed to the fact that renal biopsy had not been performed on all the patients. We think that the majority of the patients who were not undergone renal biopsy and responsive to steroids histopathologically consist of MCD.

Resistance to steroids among patients with INS was reported to be 10%.Citation26 Anochie et al.Citation27 reported steroid resistance in their patients as 20%. In a study from Saudi ArabiaCitation28 this rate was 8% and Banaszak and BanaszakCitation23 reported this rate as high as 31% in children who had been followed up between 1996 and 2005. In our study, 19.6% of the patients were resistant to steroids. The different rates in the literature can be attributed to the genetic differences among races.

Resistance to steroids is the most important risk factor to develop CKD in INS. Ejaz et al.Citation19 and Ehrich et al.Citation29 detected that FSGS formed the majority of patients with SRNS. Among patients with FSGS, CKD developed in 23% and ESRD developed in 21%, respectively, within the first year after diagnosis.Citation30 In concordance with these studies 85.7% of our patients with FSGS were resistant to steroids and 26.1% of these patients developed CKD and 7.1% of them developed ESRD.

The prognosis of INS in children largely depends on the response to corticosteroids and this observation is detected in most of the previous studies.Citation5,Citation17,Citation31–35 In our study population, 96% of steroid-responder patients went into complete remission; whereas only 46% of the steroid non-responder patients did. Moreover, none of the steroid responders developed CKD and ESRD while 11% of steroid non-responder patients developed CKD and 4.1% developed ESRD. Among LR patients 80% of children remitted completely and 1 (6.7%) developed ESRD.

In conclusion, INS is a common disorder in childhood. Intercurrent infections and response to steroid therapy are the most important factors affecting the prognosis of the disease. Hematuria and hypertension at presentation are found to be related with resistance to steroids while frequency of relapses is mostly affected by age and gender. Determining the high risk patients for morbidity and mortality, and with appropriate treatment the prognosis would be better.

Declaration of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Valentini RP, Smoyer WE. Nephrotic syndrome. In: Kher K, Schnaper W, Makker S, eds. Clinical Pediatric Nephrology. 2nd ed. London: Informa UK Ltd; 2007:155–183

- Nephrotic syndrome in children: Prediction of histopathology from clinical and laboratory characteristics at time of diagnosis. A report of the International Study of Kidney Disease in Children. Kidney Int. 1978;13:159–165

- Koskimies O, Vilska J, Rapola J, Hallman N. Long term outcome of primary nephrotic syndrome. Arch Dis Child. 1982;57:544–548

- Mekahli D, Liutkus A, Ranchin B, et al. Long term outcome of idiopathic steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome: A multicenter study. Pediatr Nephrol. 2009;24:1525–1532

- Bircan Z, Yavuz Yilmaz A, Katar S. Childhood idiopathic nephrotic syndrome in Turkey. Pediatr Int. 2002;44:608–611

- Eke FU, Eke NN. Renal disorders in children: A Nigerian Study. Pediatr Nephrol. 1994;8:383–386

- Abdurrahman MB, Elidrissy ATH, Shipkey FH, Rasheed SA, Mugerien MA. Clinicopathological features of childhood nephrotic syndrome in Saudi Arabia. Ann Trop Paediatr. 1990;10:125–132

- Mc Donald NE, Wolfish N, Mclaine P, Phipps P, Rossier E. Role of respiratory viruses in exacerbation of primary nephrotic syndrome. J Pediatr. 1986;108:378–382

- Yap HK, Han EJ, Heng CK, Gong WK. Risk factors for steroid dependency in children with idiopathic nephritic syndrome. Pediatr Nephrol. 2000;16:1049–1052

- Bagga A. Revised guidelines for management of steroid-sensitive nephrotic syndrome. Indian J Nephrol. 2008;18(1):31–39

- American Academy of Pediatrics. Immunization in special clinical circumstances. In: Pickering LK, Baker CJ, Long SS, McMillan JA, eds. Red Book: 2006 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases. 27th ed. Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2006:67–104

- American Academy of Pediatrics, Committee on Infectious Disease. Recommendations for the prevention of pneumococcal infections, including the use of pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (Prevenar), pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine and antibiotic prophylaxis. Pediatrics. 2000;106:362–366

- Fakhouri F, Bocquet N, Taupin P, et al. Steroid-sensitive nephrotic syndrome: From childhood to adulthood. Am J Kidney Dis. 2003;41:755–757

- Rüth EM, Kemper JM, Leumann EP, Laube GF, Neuhaus TJ. Children with steroid-sensitive nephrotic syndrome come of age: Long term outcome. J Pediatr. 2005;147:202–207

- Brodehl J. Conventional therapy for idiopathic nephrotic syndrome in children. Clin Nephrol. 1991;35(Suppl 1):S8–S15

- Trompeter RS. Immunosuppressive therapy in the nephrotic syndrome in children. Pediatr Nephrol. 1989;3:194–200

- Davutoğlu M, Ece A, Bilici M, Dagli A. Steroid responsiveness of children with idiopathic nephrotic syndrome in southeastern region of Turkey. Ren Fail. 2007;29:855–859

- White RH, Glasgow EI, Mills RJ. Clinicopathological study of nephrotic syndrome in childhood. Lancet. 1970;7661:1353–1359

- Ejaz I, Khan HI, Javaid BK, Rasool G, Bhatti MT. Histopathological diagnosis and outcome of pediatric nephrotic syndrome. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2004;14:229–233

- Bonilla-Felix M, Parra C, Dajani T, et al. Changing patterns in the histopathology of idiopathic nephrotic syndrome in children. Kidney Int. 1999;55(5):1885–1890

- Mortazavi F, Khiavi YS. Steroid response pattern and outcome of pediatric idiopathic nephrotic syndrome: A single-center experience in northwest Iran. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2011;7:167–171

- Gulati S, Sengupta D, Sharma RK, et al. Steroid resistant nephrotic syndrome: Role of histopathology. Indian Pediatr. 2006;43(1):55–60

- Banaszak B, Banaszak P. The increasing incidence of initial steroid resistance in childhood nephrotic syndrome. Pediatr Nephrol. 2012;27:927–932

- Şirin A. Nefrotik sendrom. In: Neyzi O, Ertuğrul T, eds. Pediatri 2. 3th ed. Türkiye: Nobel Tıp Kitabevleri; 2002:1184–1186

- The primary nephrotic syndrome in children: Identification of patients with minimal change nephrotic syndrome from initial response to prednisone. A report of the International Study of Kidney Disease in Children. J Pediatr. 1981;98(4):561–564

- Niaudet P. Steroid-resistant idiopathic nephrotic syndrome in children. In: Avner ED, Harmon WE, Niaudet P, eds. Pediatric Nephrology. 5th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins; 2004:557–578

- Anochie I, Eke F, Okpere A. Childhood nephrotic syndrome: Change in pattern and response to steroids. J Natl Med Assoc. 2006;98(12):1977–1981

- Alhassan A, Mohamed WZ, Alhaymed M. Patterns of childhood nephrotic syndrome in Aljouf Region, Saudi Arabia. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl. 2013;24(5):1050–1054

- Ehrich JH, Geerlings C, Zivicnjak M, Franke D, Geerlings H, Gellermann J. Steroid-resistant childhood nephrosis: Over diagnosis and undertreated. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2007;22(8):2183–2193

- Focal segmental glomerulosclerosis in children with idiopathic nephrotic syndrome. A report of the Southwest Pediatric Nephrology Study Group. Kidney Int. 1985;27:442–449

- Sinha A, Bagga A. Nephrotic syndrome. Indian J Pediatr. 2012;79(8):1045–1055

- El Husseini A, El-Basuony F, Mahmoud I, et al. Long-term effects of cyclosporine in children with idiopathic nephrotic syndrome: A single centre experience. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2005;20:2433–2438

- Hodson EM, Knight JF, Willis NS, Craig JC. Corticosteroid therapy for nephrotic syndrome in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003;1:CD001533

- Ponticelli C, Edefonti A, Ghio L, Rizzoni G, Rinaldi S, Gusmano R. Cyclosporine versus cyclophosphamide for patients with steroid-dependent and frequently relapsing nephrotic syndrome: A multicenter randomized controlled trial. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1993;8(12):1326–1332

- Seikaly MG, Prashner H, Nolde-Hurlbert B, Browne R. Long term clinical and pathological effects of cyclosporine in children with nephrosis. Pediatr Nephrol. 2000;14:214–217