Abstract

Purpose: Since sympathovagal imbalance influences clinical phenomena, such as hypertension, diabetes mellitus, chronic kidney disease (CKD) and sleeping problems, there should be correlations between these conditions. We hypothesized that sleep quality would be correlated with estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), blood pressure and the presence of diabetes. Methods: We included 303 CKD patients in this study. We employed the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI), Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) and Short Form 36 Quality of Life Health Survey Questions (SF-36) to screen sleeping disturbances, depression and quality of life, respectively. A chart review was performed for the patients' demographics, diagnoses and certain laboratory parameters—including blood glucose, hemoglobin, albumin, calcium, phosphate, parathyroid hormone and eGFR. Multivariate logistic regression models were employed to estimate odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals. Results: We included 303 patients in this cross-sectional study. A total of 101 patients were on dialysis. In the univariate models, gender, calcium and mental component summary scores (MCS) reached a significant level of 0.1, and those covariates were included in the multivariate analysis. The reduced models included gender and MCS categories. Female gender increases the risk for poor sleep quality. In our report, evidence suggests MCS domain scores are inversely related to the risk for impaired sleep. Conclusion: Our results indicated a high burden of sleep disturbances in kidney patients. In addition, female gender and having low MCS scores may influence sleep quality in kidney patients.

Introduction

Inadequate sleep is the root of the problem that ranges from accidents to long-term health effects, including hypertension, lower quality of life and life expectancy.Citation1–3 Patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) are more prone to sleep disturbances and the condition can be underdiagnosed.Citation1 Although, the determinants of the disease are well-defined in the general population, a lack of evidence supporting the correlates in CKD patients necessitates further investigations in that area.Citation4–9 Furthermore, most of the data are from the dialysis population, and identifiers of poor sleep quality in non-dialysis CKD patients also require more research.Citation10,Citation11

We hypothesize that sleeping problems correlate with the degree of kidney dysfunction, presence of diabetes mellitus and hypertension, and these conditions might affect quality of life in CKD patients. The prevalence of impaired sleep should be higher when kidney disease is more advanced, such as in the dialysis stage.

The primary objective of this study is to assess the factors associated with sleep quality in CKD patients. The point prevalence of sleeping problems was also studied.

Methods

Patient's enrollment

This is a cross-sectional study of adult CKD patients recruited between September 2012 and December 2012 from the St. John's area. All CKD patients were eligible to enroll, regardless of complaints related to sleep. In this study, only estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was employed for defining reduced kidney function due to the lack of albumin creatinine ratio (ACR) data. We excluded those with severe vision and/or hearing problems that interfered with the informed consent process.

We also recorded patient's demographics, diagnosis, laboratory data—including glucose, hemoglobin, albumin, calcium, phosphate, parathyroid hormone and eGFR, single blood pressure measurement, dialysis-related information for those who were on dialysis, including dialysis modality, vintage, type of vascular access and interdialytic weight gain (IWG).

The body mass index (BMI) was calculated with the following formula: weight (kg)/height2 (m2). Dialysis vintage was calculated in days, since the first dialysis treatment started. The IWG equals to sum of the net ultrafiltration per dialysis session in the last six dialysis sessions, including the day of the interview divided by six.

We included blood pressure parameters, such as systolic blood pressure (SBP), diastolic blood pressure (DBP), mean arterial pressure (MAP) and pulse pressure (PP) in our study. The sitting predialysis blood pressure was recorded for dialysis patients. Sitting blood pressure measurements before the doctor's visit were also recorded for ambulatory care patients. Only one measurement was recorded. We calculated the MAP with the following formula: [(2* diastolic blood pressure) + systolic blood pressure] ÷ 3; we calculated the PP with the following formula: [Systolic blood pressure – diastolic blood pressure].

The results related to sleep apnea have been reported previously.Citation12

Ethics

This study was approved by the provincial Health Research Ethics Authority and Research Proposal Approval Committee of Eastern Health.

The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index

We employed the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) to screen sleeping problems in our study cohort.Citation13 The questionnaire asks a total of 18 questions with a score range of 0–21. The PSQI has seven domains: subjective sleep quality, sleep latency, sleep duration, habitual sleep efficiency, sleep disturbances, use of sleep medication and daytime dysfunction over the last month.Citation13 A sum of the seven component scores produces a global score. The tool indicated test–retest reliability and validity.Citation13,Citation14

A total score was obtained for each participant by adding the scores from seven components of the PSQI. A total score greater than five indicates poor sleep, while a total score equal to or lower than five indicates good sleep.

The Beck Depression Inventory

We used the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) for depression screening in our study. The BDI is used to measure severity of depression and has 21 categories.Citation15,Citation16 The tool was validated against the structured clinical interview with a high degree of reliability and validity in the general population.Citation15 Later on, the instrument was also validated for the dialysis population with a score cut-off of 16.Citation17,Citation18 The standard version of the BDI has 21 questions, and each question is scored on a 4-point scale (0–3). The total score range lies between 0 and 63, and higher scores are consistent with more severe depression.

The practice recommendation for depression and anxiety screening in dialysis patients is an evaluation at dialysis initiation and every six months hereafter, according to the Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative (KDOQI) guidelines.Citation19

Quality of life

We used the Short Form 36 Quality of Life Health Survey Questions (SF-36) (Medical Outcomes Trust, Boston, MA) version 2.0 in this study.Citation20 The tool has been validated for CKD patients.Citation21 The SF-36 can be used for comparing populations, screening patients and comparing the health benefits of different treatment options.Citation20

The SF-36 form has 36 questions, eight scales and two summary measures. The eight scales are as follows: physical functioning (PF), role physical (RP), bodily pain (BP), general health (GH), vitality (VT), social functioning (SF), role emotional (RE) and mental health (MH). PF, RP and BP contribute to the physical component summary (PCS), whereas MH, RE and SF contribute to the mental component summary scores (MCS). VT, GH and SF contribute to both summary measures.Citation22,Citation23 The scoring software is used to compute norm-based scores for each component score (Quality Metric Health Outcomes™ Scoring Software 4.5).Citation24

Statistical analysis

The analytical plan included descriptive and inferential statistics. We assessed central tendency, dispersion and distribution for continuous variables. Consequently, we used mean (standard deviation; SD) for normally distributed and median (inter-quartile range; IQR) for non-normally distributed data to summarize the values. Frequencies (numbers) and proportions were used for categorical variables in the dialysis and non-dialysis groups.

Furthermore, the hypothesis of “sleep quality” can be predicted by “the presence of diabetes, blood pressure parameters (systolic, diastolic, pulse and MAP)”, severity of kidney dysfunction and CKD–bone and mineral disorders was tested in this study cohort. We also included potential confounders, such as age, sex and BMI in our multivariate models. The main exposure variable of interest was eGFR.

Logistic regression, including univariate, multivariate and reduced models, was performed to test the hypothesis. We employed the Wald statistic technique to test model fit and significance of individual coefficients. Odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were obtained. We included univariate models at alpha = 0.10.Citation25 Two-sided tests were employed with a significance level of 0.05 in our final models. All data analyses were performed using R studio, Version 0.96.122 (Integrated development environment for R, Boston, MA).

Since the linearity assumption was violated for MCS scores, quartiles ranges were used to categorize the variable. Category 1 (percentile < 25%) included values less than 49.4, category 2 (percentile 25–50%) included values between 49.4 and 55.5, category 3 (percentile 50–75%) included values between 55.5 and 59.5 and category 4 (percentile > 75%) included 59.5 and 73. Subsequently, MCS score was used as a categorical variable in the multivariate and reduced models. A difference contrast (reverse Helmert contrast) method was selected to compare the categories of MCS with the mean of the previous categories of the variable in the logistic regression technique.

Results

We included 303 patients (125 females, 178 males with mean age 62.7 ± 14.5 years) in this cross-sectional study (). Among these, 202 patients (86 females, 116 males, mean age 63.8 ± 14.4) had non-dialysis CKD, and 18 patients had a kidney transplant. A total of 101 (39 females, 62 males, mean age 60.6 ± 14.4) were on dialysis: seven patients were on peritoneal dialysis (PD), two patients were on home hemodialysis (HD) and 92 patients were in-centre HD treatments.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of the participants divided by sleep quality.

An arteriovenous (AV) fistula was the method of choice for a vascular access in most of the HD patients. A total of 55 (58%) HD patients had an AV fistula, while 39 (42%) patients had a catheter. Of the seven PD patients, three patients were on automated PD, while four patients were on continuous ambulatory PD.

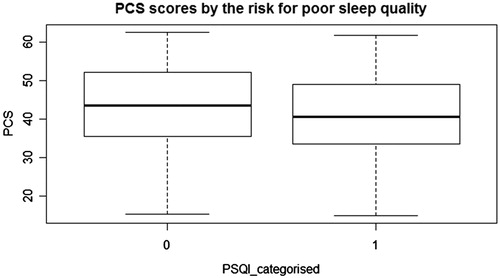

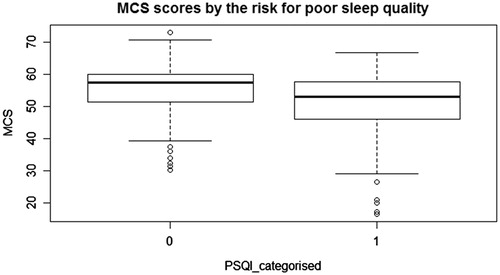

Sleep quality was evaluated with the PSQI and all participants completed the survey. We categorized participants as good and poor sleepers with a cut-off value of five, as previously noted. We used the BDI for depression screening and SF-36 for quality of life and all participants completed the surveys, except two people. and indicate PCS and MCS scores of the SF-36 questionnaire categorized by the PSQI. The median scores of PCS and MCS are higher in good sleepers ( and ).

Figure 1. Box plot indicating PCS scores and PSQI; abbreviations: PCS: physical component summary, PSQI categorised: The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index categorised by the total score.

Figure 2. Box plot indicating MCS scores and PSQI; abbreviations: MCS: mental component summary scores, PSQI categorised: The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index categorised by the total score.

Univariate analysis was performed for each predictor and potential confounder variables. Age, BMI, presence of diabetes mellitus, blood pressure parameters (SBP, DBP, MAP and PP), hemoglobin, glucose, PTH, P, Ca and eGFR did not reach the significance level for retention in the model (p < 0.1). Thus, those factors were excluded from the multivariate analysis. In the univariate models, gender, Ca and MCS scores reached a significant level of 0.1, and those covariates were included in the multivariate analysis. The reduced models included gender and MCS categories. Female gender increases the risk for poor sleep quality (). In our report, evidence suggests MCS domain scores are inversely related to the risk for impaired sleep.

Table 2. Variables associated with sleep quality.

Discussion

We included a total of 303 CKD patients from the St John's area and our results indicated: (1) MAP and PP were significantly higher in the dialysis group; (2) sleep quality was lower in the dialysis group; (3) female gender was associated with lower sleep quality; (4) patients with low MCS scores indicated high risk for impaired sleep.

Our results showed that female gender was associated with a higher likelihood for poor sleep quality. Parallel to our findings, evidence suggested that female gender was associated with poor sleep.Citation26 In contrast to these findings, few reports failed to show the correlation between sleep quality and gender.Citation27–29 The heterogeneity between the study results is likely due to differences in the study populations, study implementations or by chance alone. The PSQI was employed for the assessment of sleep problems, excluding the report by Davis and others, which employed the Pediatric Sleep Questionnaire.Citation29 The reports were all cross-sectional designs. As a result, study design and measurement tools were similar across studies.

We tested quality of life summary scales for an association with sleep quality. The results indicated that the MCS domain of SF-36 was correlated with sleep quality, and the most prominent effect was seen when comparisons were made between the highest percentile group and the lower percentiles. These findings were supported by previous studies in CKD patients.Citation30–32 Since sleep may influence physical and mental wellbeing, the link between sleep and life quality is an expected finding.

We found that age was not an independent factor for sleep quality in CKD patients. The correlation between age and sleep quality has been studied in CKD patients with mixed results. Few reports supported our findings both in healthy population and in dialysis patients.Citation33,Citation34 In contrast, two studies in PD patients indicated that age might influence sleep quality.Citation30,Citation35 The mixed results regarding the effects of age on sleep quality may be attributed to the differences in the study populations and measurement tools. The gold standard for diagnosis of sleep disorders is polysomnography, which many studies fail to employ. This may be a reason for a potential measurement bias.

We reported that abnormal blood pressure parameters and sleep quality were not related in our logistic models. However, MAP and PP were significantly higher in the dialysis group, when compared to the non-dialysis group. Further, in our study, we did not find any significant correlation between SBP and DBP with sleep impairment. Evidence failed to show the association between hypertension and sleep quality using the PSQI in previous reports.Citation19,Citation26,Citation36 Nevertheless, several studies reported that there was an association between non-dipper status, which was defined as blood pressure drop less than 10% during sleep, and sleep quality using the PSQI.Citation8,Citation9,Citation37,Citation38

The present results demonstrate that eGFR as a continuous variable was not a significant determinant for sleep quality in our study cohort (OR: 1.006 per 1 mL/min difference in eGFR, 95% CI: 0.98–1.03, p: 0.63). This finding was supported by a previous report in CKD patients.Citation39 In contrast to these findings, inadequate sleep has been associated with the severity of kidney dysfunction, according to another report by Plantinga and others.Citation11

Our findings indicated that the presence of diabetes mellitus was not an independent predictor for poor sleep quality. Furthermore, the rate of diabetes did not differ between poor sleepers and good sleepers in our study (48% vs. 45%, p: 0.5). The prevalence of diabetes in those with impaired sleep was previously studied. The reports indicated that diabetes was more common in those with high PSQI global scores (14.9% vs. 8.8%, p < 0.001).Citation38

We have demonstrated that BMI and IWG have not been associated with poor sleep quality in our study cohort. Similarly, evidence indicated that the PSQI global score was not correlated with BMI.Citation28,Citation37 In contrast, poor sleep quality has been linked to high BMI in the adolescent population without CKD.Citation40

Strengths of this study include methods related to administration and scoring of the instruments and large sample size with participants from the same centre. This reduces the risk of bias due to potential variability between centers. Additionally, we included all potential confounder variables and tested model fit and assumptions for modeling the relationship. Limitations of this study include a lack of gold standard for sleep disorders and single time point measurement with a cross-sectional design. Furthermore, we did not include physician-level variability into our models.

The prevalence of sleep problems is higher in kidney patients as compared to the normal population and these conditions have been related to lower quality of life and survival.Citation41–45 Our results indicated a high burden of sleep disturbances in kidney patients. In addition, female gender and having low MCS scores may influence sleep quality. Since life expectancy is already reduced in CKD patients, all appropriate measures to improve longevity and quality of life should be considered in the management.

Acknowledgments

Nigar Sekercioglu acknowledges with thanks that he received a license to use SF-36 forms and Quality Metric Health Outcomes™ Scoring Software 4.5 for this study.

Declaration of interest

Authors declared that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Hanly P. Sleep disorders and end-stage renal disease. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2008;14(6):543–550

- Ohayon MM, Guilleminault C, Priest RG, Caulet M. Snoring and breathing pauses during sleep: Telephone interview survey of a United Kingdom population sample. BMJ. 1997;314(7084):860–863

- Marin JM, Agusti A, Villar I, et al. Association between treated and untreated obstructive sleep apnea and risk of hypertension. JAMA. 2012;307(20):2169–2176

- Gellis LA, Lichstein KL, Scarinci IC, et al. Socioeconomic status and insomnia. J Abnorm Psychol. 2005;114(1):111–118

- Wickwire EM, Collop NA. Insomnia and sleep-related breathing disorders. Chest. 2010;137(6):1449–1463

- Zammit GK, Weiner J, Damato N, Sillup GP, McMillan CA. Quality of life in people with insomnia. Sleep. 1999;22(Suppl 2):S379–S385

- Taylor DJ, Lichstein KL, Durrence HH. Insomnia as a health risk factor. Behav Sleep Med. 2003;1(4):227–247

- Erden I, Erden EC, Ozhan H, et al. Poor-quality sleep score is an independent predictor of non-dipping hypertension. Blood Press Monit. 2010;15(4):184–187

- Huang Y, Mai W, Hu Y, et al. Poor sleep quality, stress status, and sympathetic nervous system activation in non-dipping hypertension. Blood Press Monit. 2011;16(3):117–123

- Beecroft J, Duffin J, Pierratos A, Chan CT, McFarlane P, Hanly PJ. Enhanced chemo-responsiveness in patients with sleep apnea and end-stage renal disease. Eur Respir J. 2006;28(1):151–158

- Plantinga L, Lee K, Inker LA, et al. Association of sleep-related problems with CKD in the United States, 2005–2008. Am J Kidney Dis. 2011;58(4):554–564

- Sleep apnea in patients with chronic kidney disease: A single center experience. Ren Fail. 2015;37(1):83–87

- Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF III, Monk TH, Berman SR, Kupfer DJ. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: A new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. 1989;28(2):193–213

- Curcio G, Tempesta D, Scarlata S, et al. Validity of the Italian version of the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI). Neurol Sci. 2013;34(4):511–519

- Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, Mock J, Erbaugh J. An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1961;4:561–571

- Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. BDI-II Manual. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation, Harcourt Brace & Company; 1987

- Watnick S, Wang PL, Demadura T, Ganzini L. Validation of 2 depression screening tools in dialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis. 2005;46(5):919–924

- Chilcot J, Wellsted D, Farrington K. Screening for depression while patients dialyse: An evaluation. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2008;23(8):2653–2659

- National Kidney Foundation. KDOQI Clinical Practice Guidelines and Clinical Practice Recommendations for cardiovascular disease in dialysis patients. Guideline 14: Smoking, physical activity, and psychological factors. Am J Kidney Dis. 2005;45(4):S60–68

- Ware JE Jr, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992;30(6):473–483

- Johansen KL, Painter P, Kent-Braun JA, et al. Validation of questionnaires to estimate physical activity and functioning in end-stage renal disease. Kidney Int. 2001;59(3):1121–1127

- Ware JE Jr. SF-36 health survey update. Spine. 2000;25(24):3130–3139

- Ware JE Jr, Kosinski M, Dewey JE. How to score version 2 of the SF-36 health survey. Lincoln, RI: QualityMetric Incorporated; 2000

- The QualityMetric Health Outcomes™ Scoring Software 4.5 [computer program]. Version 4.5.4330.22306. Available at: www.optum.com. Accessed January 10, 2013

- Mickey RM, Greenland S. The impact of confounder selection criteria on effect estimation. Am J Epidemiol. 1989;129(1):125–137

- Hung HC, Yang YC, Ou HY, Wu JS, Lu FH, Chang CJ. The association between self-reported sleep quality and metabolic syndrome. PLoS One. 2013;8(1):e54304

- Edalat-Nejad M, Qlich-Khani M. Quality of life and sleep in hemodialysis patients. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transplant. 2013;24(3):514–518

- Araujo SM, Bruin VM, Daher EF, Medeiros CA, Almeida GH, Bruin PF. Quality of sleep and day-time sleepiness in chronic hemodialysis: A study of 400 patients. Scand J Urol Nephrol. 2011;45(5):359–364

- Davis ID, Greenbaum LA, Gipson D, et al. Prevalence of sleep disturbances in children and adolescents with chronic kidney disease. Pediatr Nephrol. 2012;27(3):451–459

- Guney I, Biyik M, Yeksan M, et al. Sleep quality and depression in peritoneal dialysis patients. Ren Fail. 2008;30(10):1017–1022

- Turkmen K, Yazici R, Solak Y, et al. Health-related quality of life, sleep quality, and depression in peritoneal dialysis and hemodialysis patients. Hemodial Int. 2012;16(2):198–206

- Unruh ML, Buysse DJ, Dew MA, et al. Sleep quality and its correlates in the first year of dialysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;1(4):802–810

- Harris TJ, Nazir R, Khetpal P, et al. Pain, sleep disturbance and survival in hemodialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2012;27(2):758–765

- Monterrosa-Castro A, Marrugo-Florez M, Romero-Perez I, Fernandez-Alonso AM, Chedraui P, Perez-Lopez FR. Assessment of sleep quality and correlates in a large cohort of Colombian women around menopause. Menopause. 2013;20(4):464–469

- Li J, Guo Q, Ye X, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of sleep disturbance in continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis patients in Guangzhou, southern China. Int Urol Nephrol. 2012;44(3):929–936

- Ji-Rong Y, Hui W, Chang-Quan H, Bi-Rong D. Association between sleep quality and arterial blood pressure among Chinese nonagenarians/centenarians. Med Sci Monit. 2012;18(3):PH36–PH42

- Yilmaz MB, Yalta K, Turgut OO, et al. Sleep quality among relatively younger patients with initial diagnosis of hypertension: dippers versus non-dippers. Blood Press. 2007;16(2):101–105

- Fiorentini A, Valente R, Perciaccante A, Tubani L. Sleep's quality disorders in patients with hypertension and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Int J Cardiol. 2007;114(2):E50–E52

- Roumelioti ME, Wentz A, Schneider MF, et al. Sleep and fatigue symptoms in children and adolescents with CKD: A cross-sectional analysis from the chronic kidney disease in children (CKiD) study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2010;55(2):269–280

- Narang I, Manlhiot C, Davies-Shaw J, et al. Sleep disturbance and cardiovascular risk in adolescents. CMAJ. 2012;184(17):E913–E920

- Parfrey PS, Vavasour HM, Henry S, Bullock M, Gault MH. Clinical features and severity of nonspecific symptoms in dialysis patients. Nephron. 1988;50(2):121–128

- Unruh ML, Buysse DJ, Dew MA, et al. Sleep quality and its correlates in the first year of dialysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;1(4):802–810

- Molzahn AE, Northcott HC, Dossetor JB. Quality of life of individuals with end stage renal disease: Perceptions of patients, nurses, and physicians. ANNA J. 1997;24(3):325–333; discussion 334–325

- Elder SJ, Pisoni RL, Akizawa T, et al. Sleep quality predicts quality of life and mortality risk in hemodialysis patients: results from the Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study (DOPPS). Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2008;23(3):998–1004

- Balogun RA, Abdel-Rahman EM, Balogun SA, et al. Association of depression and antidepressant use with mortality in a large cohort of patients with nondialysis-dependent CKD. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;7(11):1793–1800