Introduction

Experimental models suggest that vitamin D deficiency contributes to myocardial capillary rarefactionCitation1 and fibrosisCitation2—processes implicated in associations of chronic kidney disease (CKD) and cardiovascular death.Citation3 However, placebo-controlled vitamin D trials have not demonstrated conclusive effects on cardiovascular structure.Citation4 Whether this reflects differences between experimental models and human physiology or insensitivity of non-invasive measures to changes in the underlying myocardial structure is uncertain. Because associations between vitamin D use and human myocardial pathology have not been reported, we analyzed myocardial histology in humans with and without exposure to exogenous vitamin D.

Brief methods

All studies were approved by the Partners Human Research Committee (Chair-Elizabeth Hohmann, MD, Protocol# 2006P001192, Date of Approval 19 July 2006. Estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was calculated from outpatient (within 4 months) or the lowest stable inpatient serum creatinine using the MDRD equation. Vitamin D use was extracted from clinical records.

Paraffin-embedded, 5 µm left ventricular sections collected at autopsy were trichrome stained and examined with light microscopy (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). Collagen deposition (≥10 representative fields, 100× magnification) was digitally quantified. Microvascular density was assessed by CD31 (Pharmingen, San Diego, CA) staining and measured at 200× (≥10 fields). Myocytes and CD-31 positive tubular structures were counted blindly, pixels were labeled, and the area measured.

Univariate differences were compared using Chi-square, t or Mann–Whitney tests. Multivariable linear regression was performed with logarithmic transition of non-normal independent variables. Analyses were performed in STATA 13.0 (STATA Corp., College Station, TX) with p < 0.05 considered significant.

Key results

Twelve of 44 subjects (27.2%) had a history of prior vitamin D use (). Age, race, sex, and renal function were similar, but eGFR was significantly lower among vitamin D users compared to non-users (15.3 [IQR: 2.0–62.1] vs. 64.9 mL/min/1.73mCitation2 [IQR: 42.3, 101.0], p = 0.03. Diabetes (p = 0.03), hyperparathyroidism (p = 0.03) and history of phosphate binding therapy (p < 0.01) were more frequent among vitamin D users compared with non-users.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics.

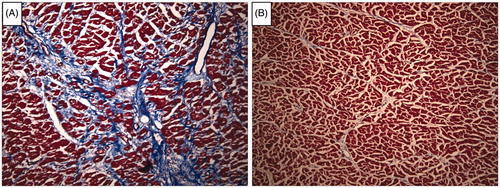

In models adjusted for age, sex, CKD class, and hypertension, vitamin D use was associated with statistically significant decreases in myocardial fibrosis (β = −3.9%, 95% CI: −7.3, −0.4, , ). Microvascular density and cardiomyocyte number were not significantly different and trends in cardiomyocyte size did not achieve significance. Results were qualitatively similar among individuals with baseline CKD, and in models adjusting for sex, age, diabetes and ace inhibitor/angiotensin receptor blocker use or the use of erythropoietin stimulating agents (not shown).

Figure 1. Fibrosis of the left ventricle in individuals with and without exogenous vitamin D exposure. Representative images of left ventricle from patients with (A) and without (B) exogenous vitamin D exposure. Left ventricle sections were paraffin embedded, sectioned at 5 µm and trichrome stained using standard techniques and visualized at 100× magnification.

Table 2. Crude and adjusted associations of vitamin D and myocardial histology.

Discussion

Vitamin D reverses myocardial capillary rarefactionCitation1 and deficiency contributes to myocardial fibrosis in experimental models.Citation2 Despite compelling science, trials have been unable to detect a correlation of vitamin D use and MRI-assessed left ventricular mass index or echocardiography-based assessment of diastolic function.Citation4 Whether this reflects differences in biology or a failure of non-invasive measures to detect these histological changes is uncertain. Cardiac fibrosis, a main predictor of cardiac mortality, was not directly assessed in these studies. We examined human left ventricle and found that vitamin D use was independently associated with decreased myocardial fibrosis but not with microvascular supply or cardiomyocyte number. Effect on myocyte size was of only borderline significance.

Our study is based on the use of post-mortem samples from a single center. The retrospective nature of the study as well as incomplete or unavailable data regarding circulating mineral and bone metabolites (calcium, phosphorous, parathyroid hormone, and fibroblast growth factor-23) or vitamin D analogue, dose or duration of use are limitations of the study design. However, associations between exogenous vitamin D and human myocardial histology have not been previously reported. Our data suggest that vitamin D reduces myocardial fibrosis but has less profound impact on microvascular supply, myocyte number and myocyte size when adjusted for confounding variables.

Our findings imply that non-invasive measures of ventricular mass which integrate the combined effects of collagen accumulation and myocyte hypertrophy may be insufficiently sensitive to detect important effects of vitamin D analogues on fibrosis alone. New vitamin D trials examining specific measures of myocardial fibrosis and changes in the underlying mechanistic pathways or clinical outcomes may be worthwhile to unravel the association of vitamin D deficiency with increased cardiovascular mortality.Citation5

Our study had limitations including sample size, non-randomized use of multiple vitamin D formulations, lack of information on exogenous vitamin D duration, and estimation of GFR. Nevertheless, this is the first report of associations between vitamin D and human myocardial histology. The association with fibrosis but not with other histologic parameters provides novel insights into the discordant results between experimental models and recent trials that merit further study. The results also provide motivation for additional cardiovascular outcome trials of vitamin D in individuals with and without CKD.

Declaration of interest

The authors have no conflicts to declare.

This work was funded by the University Medical Center of Göttingen; the Paul Teschan Research Fund; the American Society of Nephrology (Carl Gottschalk Award); the American Heart Association (Scientist Development Grant); and the SFB1002/C01 DFG grant.

References

- Repo JM, Rantala IS, Honkanen TT, et al. Paricalcitol aggravates perivascular fibrosis in rats with renal insufficiency and low calcitriol. Kidney Int. 2007;72:977–984

- Panizo S, Barrio-Vazquez S, Naves-Diaz M, et al. Vitamin D receptor activation, left ventricular hypertrophy and myocardial fibrosis. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2013;28:2735–2744

- Charytan DM, Padera R, Helfand AM, et al. Increased concentration of circulating angiogenesis and nitric oxide inhibitors induces endothelial to mesenchymal transition and myocardial fibrosis in patients with chronic kidney disease. Int J Cardiol. 2014;176:99–109

- Thadhani R, Appelbaum E, Pritchett Y, et al. Vitamin D therapy and cardiac structure and function in patients with chronic kidney disease: The PRIMO randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2012;307:674–684

- Hocher B, Reichetzeder C. Vitamin D and cardiovascular risk in postmenopausal women: How to translate preclinical evidence into benefit for patients. Kidney Int. 2013;84:9–11