Abstract

Purpose: We aimed to evaluate the effectiveness of the endourologic management of forgotten and/or encrusted ureteral stents together with our single-center experience.

Materials and methods: Fifty-four patients with forgotten double-J ureteral stents were treated in our center between January 2008 and March 2014. Encrustation and the related stone burdens were estimated by using computerized tomography and kidney–ureter–bladder radiography. The management method was chosen based on the stone burden or clinical and radiological findings.

Results: Fifty-four patients, 39 males and 15 females, were included in the study. The average age of the patients was 38.2 ± 25.06 (2–86) years. The average indwelling time of the ureteral stents was 22.6 ± 30.3 (6–144) months. Six of the patients with forgotten stents had solitary kidneys. The double-J stent (DJS) was fragmented in four (7.4%) patients. A urinary system infection was present in 15 (27.7%) of the patients. The ureteral stents and related stones were successfully removed without any complications by combined endourologic techniques to achieve a stone-free state in all patients except for patient with 110 months of forgotten stent time in whom nephrectomy was performed for a nonfunctioning kidney related to the forgotten stent.

Conclusions: Forgotten/encrusted DJS may lead to complications in a range of urinary system infections, up to a loss of renal function. They can be safely and successfully removed, and the renal function can be preserved by endourologic techniques, starting with the least invasive procedures in centers highly experienced.

Introduction

Ureteral stents have been widely utilized since their first use in 1967.Citation1 Double-J stents (DJS) have been a basic part of many urologic procedures when needed, following open or endoscopic ureteral surgery for retroperitoneal tumors or fibrosis, ureteral strictures, ureteropelvic junction obstructions, or the treatment of obstructing ureteral stones.Citation1,Citation2 Stents may also be inserted following iatrogenic injuries of the ureters or to protect and define the ureter in complex abdominal procedures in a preoperative period.Citation3

In the last decade, new materials and stents have been designed in the presence of important technological innovations and developments to improve patient tolerance and to overcome stent-related problems.Citation4 Despite significant progress, the utilization of DJS is not complication-free. Sometimes, DJS may be left in place for a long duration due to physician and/or patient negligence.Citation5 Serious complications such as stone formation, migration, fragmentation, and encrustation may occur when DJS remains inside the patient for an extended period of time.Citation6 The management of forgotten DJS may be time-consuming, difficult, complex, risky, and expensive.Citation7

Various combinations of endourologic methods have been reported for the management of forgotten DJS (FUS) in the literature. However, there are no algorithmic approaches in urology guidelines for forgotten stents in both adults and children, meaning their treatment may be complicated and difficult for urologists.

We aimed to present our management methods in patients with forgotten and/or encrusted DJS. Together with our experience, it may constitute the largest single-center series reported in the literature up to the present time.

Materials and methods

Fifty-four patients who were treated in our center between January 2008 and March 2014 with the indication of forgotten (> 6 months) double J ureteral stents were analyzed retrospectively. Patient data were obtained by chart reviews. The indwelling time of the stent was calculated from the time of insertion to removal.

The preoperative evaluation consisted of a urinalysis, blood creatine level, whole blood count, and a urine culture with an antibiotic sensitivity test. A negative urine culture result was documented in all patients before endourologic intervention. In patients with positive urine culture results, an intervention was performed after antibiotic treatment. All patients received antibiotic prophylaxis preoperatively. Kidney–ureter–bladder (KUB) radiography, urinary system ultrasonography (US), and/or non-contrast computerized tomography (NCCT) and/or intravenous pyelography were performed in all patients to evaluate stone burdens and stent encrustation. The renal function was evaluated by diethylenetriamine penta-acetic acid renography when necessary.

The patient anatomy, stent encrustation, related stone burden, and degree of complexity of the situation (e.g., broken or migrated stent) were evaluated with the help of KUB radiography and/or NCCT. Treatment decisions were made on the basis of imaging findings and the clinical presentation. If the stented kidney was nonfunctional, nephrectomy could be considered a cautious option to avoid the morbidity of numerous interventions.

Patients needed various endourologic procedures under general or local anesthesia in one or more sessions. To remove the stent and related stone burden, various combinations of the following were used: shockwave lithotripsy (SWL), simple cystoscopic stent removal (SCSR), endoscopic cystolithotripsy (EnCL), ureterorenoscopy (URS), retrograde intrarenal surgery (RIRS), percutaneous cystolithotripsy (PCCL), and percutaneous nephrolithotomy (PCNL).

A PCCL and PCNL were performed using a rigid 15F or 24F nephroscope. The URS was done using 8F/9.8F or 4.5F/6.5F semirigid ureteroscopes under fluoroscopic guidance. A holmium laser lithotripter or pneumatic lithotripter was used as an intracorporeal lithotripter. Extracorporeal SWL was performed using the Siemens Lithostar Modularis (AG Healthcare, Munich, Germany).

A RIRS operation was performed at the lithotomy position on the endoscopy table, enabling fluoroscopic visualization. First, a hydrophilic guide wire was introduced into the renal pelvis by semirigid ureteroscope with the guidance of fluoroscopy. To work under low intrarenal pressures with optimal visualization, a 9.5F ureteral access sheath was placed through the hydrophilic guide.

Only encrustation/stones immediately adjacent to the encrusted tube were used to calculate stone burden with the following formula:

stone burden = length × width of stone on plain X-ray.Citation8

The encrustation was graded based on the calculated area as light (less than 100 mm2), moderate (100–400 mm2), or severe (greater than 400 mm2).

KUB radiography and renal US were used to evaluate the postoperative residual stone burden. Patients suspected of having urinary stones or hydronephrosis were evaluated by NCCT. Patients were considered stone-free if the postoperative imaging studies revealed no stones greater than 3 mm.

Results

Fifty-four patients, 39 (72.2%) males and 15 (27.8%) females, were included in the study. The mean age of the patients was 38.2 ± 25.06 (2–86) years. The mean indwelling time of the DJS was 22.6 ± 30.3 (6–144) months. The average duration of hospitalization was 3.77 ± 3.35 (1–15) days. includes an outline of the initial indications for stenting, patient demographic characteristics, the indwelling time of a stent, the degree and site of encrustation, the type of procedure, and the length of the hospital stay.

Table 1. Patients and characteristic.

Urolithiasis, persistent hydronephrosis during pregnancy, ureteral reconstructive surgery, and renal transplantation were the indications for stenting in 45 (83.3%), 5 (9.2%), 3 (5.5%), and 1 (1.8%) patients, respectively. Six of the patients (11.1%) with forgotten ureteral stents had solitary kidneys. Four patients (7.4%) had fragmented DJS. Preoperative urine cultures were positive in 15 (27.7%) of the patients in whom antibiotic therapy preceded intervention.

A preoperative evaluation of patients’ revealed encrustations in 40 KUB radiographs; 14 KUB radiographs in patients showed none. While preoperatively, the evaluation for encrustation was by KUB radiography only in 15 patients, 38 patients were evaluated by KUB radiography together with NCCT. NCCT detected encrustation in three patients in whom KUB radiography showed none.

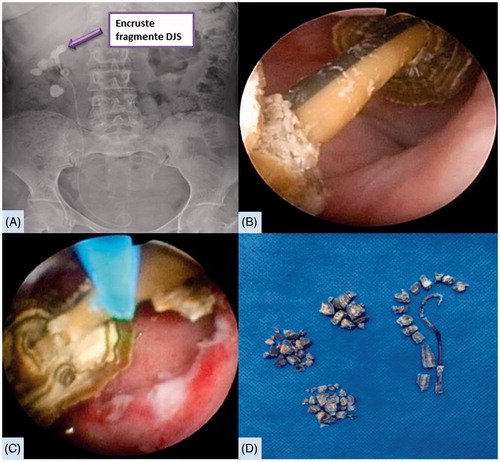

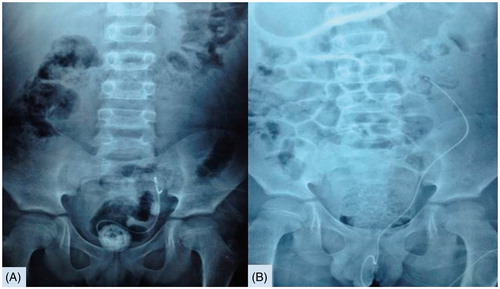

The initial management consisted of SWL in 18 patients. In 5 patients, following SWL, stents were removed successfully by SCSR; 13 patients necessitated other endoscopic procedures. In 11 patients without any encrustations showing in KUB radiography, stents were removed by SCSR under fluoroscopic guidance. Endoscopic cystolithotripsy was used in five cases to remove the stent with encrustation at the distal end. EnCL was combined in two cases with URS. In five male patients with severe encrustations at the distal end of the stent, PCCL was used. It was combined with URS in a pediatric patient who had a severely encrusted bladder accompanied by a ureteral stone. In four cases, PCNL was performed for severe encrustations proximal to the stent and/or related renal stones. In five cases, only a URS procedure with intracorporeal lithotripsy was performed. Nine patients with kidney and bladder encrustations were treated by EnCL and PCNL. A URS was combined with a PCNL in one patient. RIRS was used for three patients with encrustations proximal to the stent. EnCL + URS + PCNL was used for one patient in whom the forgotten stent time was 60 months. One patient with 122 months of forgotten stent time was treated by PCNL, followed by holmium laser lithotripsy with the insertion of a flexible cystoscope through the percutaneous entrance site. Additionally, removal of the fragmented encrusted stent resulted in a stone-free state (). Nephrectomy was done for the indication of a non-functional atrophic kidney in a 53-year-old patient who had a DJS for hydronephrosis during pregnancy and forgotten for 110 months.

Figure 1. (A) KUB radiograph view of associated stone burden and encruste fragmented DJS. (B) During PCNL view of within the kidney of encruste fragmented DJS. (C) Encruste fragmented DJS applying of holmium laser lithotripsy through percutaneous access tract by the flexible cystoscope. (D) Encruste fragmented DJS and all stones in right kidney were removed by PCNL.

We were extremely careful during the removal of forgotten DJS. Following removal, we checked the integrity of the stents meticulously. Selected complicated and special cases are shown in and , together with their data.

Figure 2. (A) KUB radiograph appearance of left lower ureteral stone and part in the bladder of forgotten severe encruste DJ stent for 41-month. (B) Severe encruste distal part of DJS and left lower ureteral stone were removed after PCCL and URS combine endourologic treatment.

In 12 patients, intraoperative intense ureteral manipulation necessitated DJS following the procedure. They were removed two weeks after intervention. By using combined endourologic techniques, encrusted stents and their related stone burdens were removed without any complications, leaving the patients free of stones.

Discussion

The encrustation of forgotten stents with a severe stone burden is a serious problem due to recurrent urinary tract infections, hematuria, urinary tract obstructions, and renal failure.Citation9 The etiology of encrustation is multifactorial. The well-known risk factors for stent encrustation are prolonged duration of stenting, urinary sepsis, previous history or simultaneous occurrence of stone disease, chemotherapy, chronic renal failure, and metabolic or congenital anomalies.Citation10 In our case series with forgotten DJS, the most prominent factor was the previous existence of urolithiasis. Conflicting reports have been published about the effect of stent composition on the severity of encrustation. Tunney et al.Citation11 observed that the risk of encrustation and fragmentation is dependent on the type of stent material, with silicone being the least prone to encrustation, followed by polyurethane, Si–litek®, PercuflexTM, and hydrogel-coated polyurethane. Conversely, Wollin et al.Citation12 reported that the type and duration of stenting were not significantly correlated with the amount of encrustation in their observation of removed stents. Because our study was retrospective and some of the stents were placed outside our center, the materials that composed the stents were unknown.

The prolonged indwelling time of stents increases the prevalence and severity of all complications. Serious complications, even death, may occur because of stenting for a period longer than originally planned, or following unintentional stenting for longer than six months.Citation13 These stents may cause serious morbidity and mortality due to upward migration and fragmentation, knot formation, and significantly dense stone-loaded encrustation.Citation14 Their management necessitates combined endourologic interventions or, rarely, an open surgical approach. The most important risk factor for stent encrustation is the placement time of the stent.Citation15 El-Faqih et al.Citation16 reported that the stent encrustation rate increased from 9.2% in less than 6 weeks to 47.5% between 6 and 12 weeks, and up to 76.3% in later than 12 weeks. Other factors in the series were a previous history of urolithiasis, urinary materials dissolved in high concentrations, the type of stent material, the existence of bacterial colonization, and pregnancy.Citation11,Citation17 In our series, the average removal time was 22.3 ± 30.5 months. Significant morbidity occurred in our patient with a forgotten stenting period of 110 months, leading to a non-functioning kidney and nephrectomy.

The preoperative evaluation of patients with forgotten DJS is another important subject requiring discussion. Weedin et al.Citation18 reported that NCCT estimated the actual stone burden of encrustation proximal to the stent more accurately when compared with KUB. NCCT identifies the localization of stent encrustation precisely, because it is a preferred method for the diagnosis of urinary tract stones and stents encrusted with radiolucent uric acid calcifications.Citation19 In our series, in 3 out of 15 cases in whom only KUB radiographs were used for the preoperative evaluation of encrustations, removal of the stents was not accomplished by cystoscopy and grasping forceps, leading to unexpected additional surgical procedures. A semirigid URS was used in two patients, RIRS in one patient, and laser lithotripsy was applied to encrustations for removal of the stents. These unexpected encrustations led us to use preoperative NCCT in patients with forgotten stents. We recommend that all patients with forgotten stents be routinely evaluated by NCCT in the preoperative period.

Fragmentation is a serious complication of forgotten DJS. It is caused by loss of tensile strength due to the degeneration of stent polymers and hardening of the stent.Citation20 The fragmentation rate of ureteral stents is 0.3–10% in the literature.Citation13,Citation16 In our series, the fragmentation rate was 7.4%.

The management of forgotten and encrusted DJS is a challenging condition for endourologists. Multiple endourologic procedures may often be required due to encrustation and the related stone burden of kidney, ureter, and bladder. Rarely, open surgery may be necessary for the removal of the encrusted stent. Using a combination of SWL, PCNL, EnCL, and ureteroscopy with intracorporeal lithotripsy, clearance rates ranging from 75% to 100% has been reported.Citation20–22 SWL is the initially preferred management in patients with minimally or moderate encrusted stents. In our series, a single session of SWL was used as the initial management in 18 patients with minimal or moderate encrustations. In 13 of them, the stent could not be removed by SCSR, meriting additional endourologic procedures. If KUB radiography did not reveal any encrustation, our approach was to remove the stent by cystoscopy, carefully using grasping forceps under the guidance of fluoroscopy.

We emphasize that the most important aspect of this procedure is the avoidance of using excessive force, which may lead to serious complications such as ureteral avulsion or injuries. If encrustation was at the distal end of the stent, we tried to remove it by EnCL using laser lithotripter, avoiding excessive force. In children and adult males, when the distal end of the stent had excessive encrustation and a severe stone burden, PCCL was used because of the caliber of the urethra. When the stent could not be removed by pulling gently with a grasping forceps, a 4.5F semi-rigid URS was introduced into the ureter between the stent and ureteral wall. If encrustation was only at the distal and middle portion, the stent was removed following fragmentation by laser lithotripsy. RIRS was performed if mild encrustation or a fragmented piece of the stent existed at the proximal portion or partly inside the kidney. If the proximal part of the stent showed excessive encrustation and a related severe stone burden, a PCNL was done. Except for the nephrectomy case with a non-functioning kidney, in all cases included in our study, forgotten and/or encrusted stents were removed successfully endoscopically, without any complications, and without necessitating open surgery.

In the management of forgotten stents, endourological approaches provide required solutions. However, the ideal treatment is preventing the occurrence of forgotten DJS. A consensus has not been reached concerning the ideal dwelling or exchange time of the stents. In the literature, optimal stent dwelling time reportedly varies between 2 and 4 months.Citation2,Citation23 The stents on which recurrent encrustations were formed can be changed at an early period (6–8 weeks). On the other hand, the main etiologic factor for forgotten stents is poor patient compliance and failure to follow the recommendations. Many approaches have been recommended to solve this important health problem. However, this issue remains unsolved. Programs for close follow-up of patients with stents, including computerized monitorization programs, stent removal software, and follow-up by e-mail, have been recommended.Citation24–26 Currently, the most advised method is to send a reminder SMS (short message service, or text message) to the cell phone number of the patient and the physician in cases where the stent replacement/withdrawal time has passed. This method attempted to eliminate the possibility of neglect by the physician.Citation27

In addition to the retrospective design of our study, another limitation was the inability to collect any data on the composition of stones of our patients with encrusted DJS and/or a related heavy stone burden.

Conclusion

Forgotten/encrusted DJS may lead to complications ranging from infections of the urinary tract to the loss of renal function. When a case with a forgotten DJS is admitted, it should be kept in mind that excessive encrustation may also be encountered, and combined endourologic methods may be necessary for management. Forgotten stents can be safely and successfully managed and renal function can be preserved by means of endourologic techniques.

Disclosure statement

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Zimskind PD, Fetter TR, Wilkerson JL. Clinical use of long-term indwelling silicone rubber ureteral splints inserted cystoscopically. J Urol. 1967;97:840–844.

- Borboroglu PG, Kane CJ. Current management of severely encrusted ureteral stents with a large associated stone burden. J Urol. 2000;164:648–650.

- Kuno K, Menzin A, Kauder HH, et al. Prophylactic ureteral catheterization in gynecologic surgery. Urology. 1998;52:1004–1008.

- Beiko DT, Knudsen BE, Denstedt JD. Advances in ureteral stent design. J Endourol. 2003;17:195–199.

- Chen AS, Saltzman B. Stent use with extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy. J Endourol. 1993;7:155–162.

- Bostanci Y, Ozden E, Atac F, et al. Single session removal of forgotten encrusted ureteral stents: Combined endourological approach. Urol Res. 2012;40:523–529.

- Sancaktutar AA, Söylemez H, Bozkurt Y, et al. Treatment of forgotten ureteral stents: How much does it really cost? A cost-effectiveness study in 27 patients. Urol Res. 2012;40:317–325.

- Persky L, Lockhart JJ, Karp R, et al. The overlooked, retained double J stent. Urology. 1990;36:519–521.

- Singh V, Srinivastava A, Kapoor R, et al. Can the complicated forgotten indwelling ureteric stents be lethal? Int Urol Nephrol. 2005;37:541–546.

- Bultitude MF, Tiptaft RC, Glass JM, et al. Management of encrusted ureteral stents impacted in upper tract. Urology. 2003;62:622–626.

- Tunney MM, Keane PF, Jones DS, et al. Comparative assessment of ureteral stent biomaterial encrustation. Biomaterials. 1996;17:1541–1546.

- Wollin TA, Tieszer C, Riddell JV, et al. Bacterial biofilm formation, encrustation, and antibiotic adsorption to ureteral stents indwelling in humans. J Endourol. 1998;12:101–111.

- Monga M, Klein E, Castañeda-Zúñiga WR, et al. The forgotten indwelling ureteral stent: A urological dilemma. J Urol. 1995;153:1817–1819.

- Eisner B, Kim H, Sacco D. Repeat knot formation in a patient with an indwelling ureteral stent. Int Braz J Urol. 2006;32:308–309.

- Chew BH, Duvdevani M, Denstedt JD. New developments in ureteral stent design, materials and coatings. Expert Rev Med Devices. 2006;3:395–403.

- El-Faqih SR, Shamsuddin AB, Chakrabarti A, et al. Polyurethane internal ureteral stents in treatment of stone patients: Morbidity related to indwelling times. J Urol. 1991;146:1487–1491.

- Robert M, Boularan AM, El Sandid M, et al. Double-J ureteric stent encrustations: Clinical study on crystal formation on polyurethane stents. Urol Int. 1997;58:100–104.

- Weedin JW, Coburn M, Link RE. The impact of proximal stone burden on the management of encrusted and retained ureteral stents. J Urol. 2011;185:542–547.

- Vanderbrink BA, Rastinehad AR, Ost MC, et al. Encrusted urinary stents: Evaluation and endourologic management. J Endourol. 2008;22:905–912.

- Zisman A, Siegel YI, Siegmann A, et al. Spontaneous ureteral stent fragmentation. J Urol. 1995;153:718–721.

- Mohan-Pillai K, Keeley FX, Jr, Moussa SA, et al. Endourological management of severely encrusted ureteral stents. J Endourol. 1999;13:377–379.

- Somers WJ. Management of forgotten or retained indwelling ureteral stents. Urology. 1996;47:431–435.

- Lam J, Gupta M. Tips and tricks for the management of retained ureteral stents. J Endourol. 2002;16:733–741.

- McCahy PJ, Ramsden PD. A computerized ureteric stent retrieval system. Br J Urol. 1996;77:147–148.

- Ather MH, Talati J, Biyabani R. Physician responsibility for removal of implants: The case for a computerized program for tracking overdue double-J stents. Tech Urol. 2000;6:189–192.

- Lynch MF, Ghani KR, Frost I, Anson KM. Preventing the forgotten ureteral stent: Implementation of a web-based stent registry with automatic recall application. Urology. 2007;70:423–426.

- Sancaktutar AA, Tepeler A, Söylemez H, et al. A solution for medical and legal problems arising from forgotten ureteral stents: Initial results from a reminder short message service (SMS). Urol Res. 2012;40:253–258.