Re: László Pál, Ervin M. Árnyas, Béla Tóth, Balázs Ádám, Gábor Rácz, Róza Ádány, Martin McKee, and Sándor Szűcs. Aliphatic alcohol contaminants of illegally produced spirits inhibit phagocytosis by human granulocytes. April 2013, Vol. 35, No. 2, Pages 251–256 (doi:10.3109/08923973.2012.759962)

To the Editor

Pál et al.Citation1 claim that the unrecorded production of spirits leads not only to products contaminated with appreciable levels of aliphatic alcohols but that it is also the main source of human exposure to these substances worldwide. In their research, a sub-group of aliphatic alcohols, namely methanol, ethanol and the higher alcohols 1-propanol, 2-propanol, 1-butanol, 2-butanol, iso-butanol and isoamyl alcohol, were tested using human granulocytes in an in vitro assay. The dose-dependent effect on the inhibition of phagocytosis led the authors to believe that this mechanism may also be active in humans consuming aliphatic alcohols in illegally produced spirits and that the ingestion of illicit spirits may pose an additional risk factor for the development of ethanol-induced immunosuppression.

While we have no general problem with the underlying research of Pál et al.Citation1, we think that the rationale for the research as well as the conclusions drawn from the results need rebuttal for several reasons:

Aliphatic alcohols are suggested as “contaminants”, which suggests that the substances are not intentionally added, might imply a risk, and should be reduced as low as it can be reasonably achieved by following good manufacturing practices. This is certainly not the case, as the compounds are important for the flavor of most spirits when contained at certain levels (some spirits regulations even demand minimum contents)Citation2. Only at very high levels, the compounds are unwanted as they cause a solvent-like “fusel oil” flavor. The Joint FAO/WHO Expert Committee on Food Additives included higher alcohols (1-propanol, 1-butanol, isobutanol) in the functional class “flavoring agent” and commented that there was no safety concern at current levels of intakeCitation3.

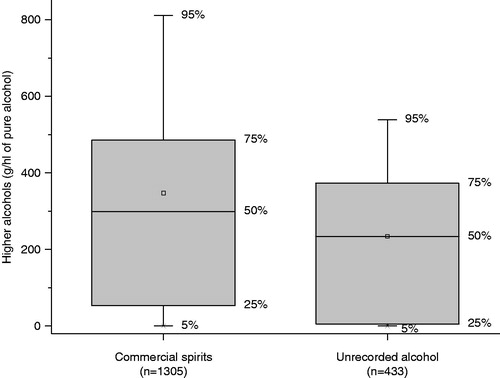

The suggestion that unrecorded spirits are the main source of human exposure to these substances is incorrect. None of the references provided by Pál et al.Citation1 demonstrate this point. On the contrary, our recent research about unrecorded alcohol has clearly invalidated this assumptionCitation4–6 – and even alcohol industry-financed studies did not detect a substantial difference between unrecorded and commercial forms of alcohol with respect to higher alcohol concentrationCitation7. To further prove our point in respect to higher alcohols, we have re-evaluated our data of 1305 commercial spirit samples, including all typical groups found on the European market, analyzed between 2006 and 2012 according to the European reference methodCitation8 and compared the results to the analyses of 433 unrecorded alcohol samples from EuropeCitation4,Citation9–12. The average sums of all higher alcohols (i.e. all analyzed aliphatic alcohols except methanol and ethanol) were 347 g/hl of pure alcohol (pa) in commercial spirits and 234 g/hl pa in unrecorded alcohol, with 95th percentiles at 811 g/hl pa (commercial) and 539 g/hl pa (unrecorded). The full distribution is shown in . According to Mann–Whitney test, the concentration of higher alcohols in unrecorded alcohol is significantly lower than in commercial alcohol (p < 0.0001). This is exactly the opposite than the assumption of Pál et al.Citation1 In light that the consumption of recorded alcohol is larger than the one of unrecorded alcohol in most parts of the world, we conclude that recorded alcohol may be the “main source of human exposure” (to higher alcohols in particular, and aliphatic alcohols in general) rather than unrecorded alcohol.

For the reasons pointed out above, the research results of Pál et al.Citation1 may be relevant for all types of alcohol consumed (except vodka and neutral alcohol, which may contain only traces of higher alcohols <0.5 g/hl pa). In fact, increased susceptibility to infectious diseases such as tuberculosis and HIV has been epidemiologically demonstrated to be related to levels of pure alcohol with no specificity for certain beveragesCitation13–15. Nevertheless, the mechanism may only be relevant for extreme heavy drinkers and alcohol-dependent people. For example, the typical blood 1-propanol levels for alcohol consumption up to 1.3‰ BAC were 0.3 mg/l for beer, 0.2 mg/l for white wine, 0.4 mg/l for brandy and 2.5 mg/l for fruit spiritsCitation16. This would be a range of ∼3–42 µM, which is below the lowest concentration (50 µM), for which an inhibitory effect could be proven by Pál et al.Citation1

Figure 1. Distribution of higher alcohols in commercial spirits and unrecorded alcohol (outliers >800 g/hl pa not shown).

Finally, as a general rule, one should wait for in vivo corroboration of in vitro results before jumping to premature deductions about potentially important and politically relevant conclusions.

Declaration of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The sampling and analysis of unrecorded alcohol has received funding from the European Community’s Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007–2013) under grant agreement no. 223059 – Alcohol Measures for Public Health Research Alliance (AMPHORA). Participant organizations in AMPHORA can be seen at http://www.amphoraproject.net/view.php?id_cont=32. Support to CAMH for the salaries of scientists and infrastructure has been provided by the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long Term Care. The contents of this paper are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the Ministry of Health and Long Term Care or other funders.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Julie Grayson for English copy-editing of the manuscript.

References

- Pál L, Árnyas EM, Tóth B, et al. Aliphatic alcohol contaminants of illegally produced spirits inhibit phagocytosis by human granulocytes. Immunopharmacol Immunotoxicol 2013;35:251–256

- Lachenmeier DW, Haupt S, Schulz K. Defining maximum levels of higher alcohols in alcoholic beverages and surrogate alcohol products. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol 2008;50:313–321

- JECFA. Summary of evaluations performed by the Joint FAO/WHO Expert Committee on Food Additives. Geneva (available online: www.inchem.org): World Health Organization; 2013

- Lachenmeier DW, Leitz J, Schoeberl K, et al. Quality of illegally and informally produced alcohol in Europe: results from the AMPHORA project. Adicciones 2011;23:133–140

- Lachenmeier DW, Schoeberl K, Kanteres F, et al. Is contaminated alcohol a health problem in the European Union? A review of existing and methodological outline for future studies. Addiction 2011;106:20–30

- Lachenmeier DW, Rehm J. Unrecorded alcohol – no worries besides ethanol: a population-based probabilistic risk assessment. In: Anderson P, Braddick F, Reynolds J, Gual A, eds. Alcohol policy in Europe: evidence from AMPHORA. Barcelona, Spain: Alcohol Measures for Public Health Research Alliance (AMPHORA); 2012:94–106

- Nuzhnyi V. Chemical composition, toxic, and organoleptic properties of noncommercial alcohol samples. In: Haworth A, Simpson R, eds. Moonshine Markets. Issues in unrecorded alcohol beverage production and consumption. New York: Brunner-Routledge; 2004:177–199

- European Commission. Commission Regulation (EC) No 2870/2000 laying down Community reference methods for the analysis of spirits drinks. Off J Europ Comm 2000;L333:20–46

- Lachenmeier DW, Ganss S, Rychlak B, et al. Association between quality of cheap and unrecorded alcohol products and public health consequences in Poland. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2009;33:1757–1769

- Lachenmeier DW, Sarsh B, Rehm J. The composition of alcohol products from markets in Lithuania and Hungary, and potential health consequences: a pilot study. Alcohol Alcohol 2009;44:93–102

- Lachenmeier DW, Samokhvalov AV, Leitz J, et al. The composition of unrecorded alcohol from Eastern Ukraine: is there a toxicological concern beyond ethanol alone? Food Chem Toxicol 2010;48:2842–2847

- Solodun YV, Monakhova YB, Kuballa T, et al. Unrecorded alcohol consumption in Russia: toxic denaturants and disinfectants pose additional risks. Interdiscip Toxicol 2011;4:198–205

- Lönnroth K, Williams BG, Stadlin S, et al. Alcohol use as a risk factor for tuberculosis – a systematic review. BMC Public Health 2008;8:289

- Rehm J, Samokhvalov AV, Neuman MG, et al. The association between alcohol use, alcohol use disorders and tuberculosis (TB). A systematic review. BMC Public Health 2009;9:450

- Baliunas D, Rehm J, Irving H, Shuper P. Alcohol consumption and risk of incident human immunodeficiency virus infection: a meta-analysis. Int J Public Health 2010;55:159–166

- Gilg T. Alkohol. In: Madea B, Musshoff F, Berghaus G, eds. Verkehrsmedizin. Fahrsicherheit, Fahreignung, Unfallrekonstruktion. Cologne, Germany: Deutscher Ärzte-Verlag; 2007:439–469