Abstract

Purpose: To report a case of psychogenic vision loss caused by false-positive anti-retinal antibody testing.

Methods: We describe a case of visual and systemic symptoms following anti-retinal antibody detection. The case was analyzed for clinical presentation, diagnosis, and consequences of false-positive testing.

Results: The patient presented with decreased vision without detectable pathology on ophthalmic examination. Tests were ordered in search of a diagnosis, including an antibody test. Following detection of anti-retinal antibodies, the patient developed worsening visual symptoms and systemic manifestations. A repeat antibody test performed at our institution revealed negative results, which, in conjunction with lack of visual field expansion, confirmed our suspicion of psychogenic vision loss.

Conclusions: Laboratory screening may be limited by test specificity and can lead to false-positive results, affecting the patient psychologically and clinically. Care must be taken in patients with positive anti-retinal antibodies to ensure the presence of definitive disease before initiation of treatment.

A 55-year-old woman with no history of cancer presented with decreased vision. She was noted to have 20/20 vision 4 years prior but now demonstrated a vision of 20/30 in her right eye and 20/40 in her left eye. Ophthalmic examination revealed no other abnormalities. Without an identifiable explanation for the patient's vision deterioration, the ophthalmologist ordered a workup for a possible ocular paraneoplastic syndrome. The patient underwent a mammogram, following which she underwent a lumpectomy that was devoid of any evidence of malignancy. A PET scan revealed no abnormal regional metabolism, and head MRI was negative for demyelinating lesions. Electroretinography (ERG) revealed decreased scotopic response in the left eye, though it was noted that she was claustrophobic and moved during the examination. Serum immunological studies showed anti-retinal antibodies against 43- and 52-kDa proteins, and treatment with methotrexate, tacrolimus, and azathioprine was initiated. During treatment, the patient was hospitalized due to severe colitis from azathioprine and tacrolimus, and the immunosuppression was discontinued. Over the next year, the patient began to experience erratic systemic symptoms, which included aphasia, tremors, and insomnia. She also experienced severe deterioration in vision and feared inevitable blindness. The patient was referred to the Mayo Clinic for complicated autoimmune retinopathy.

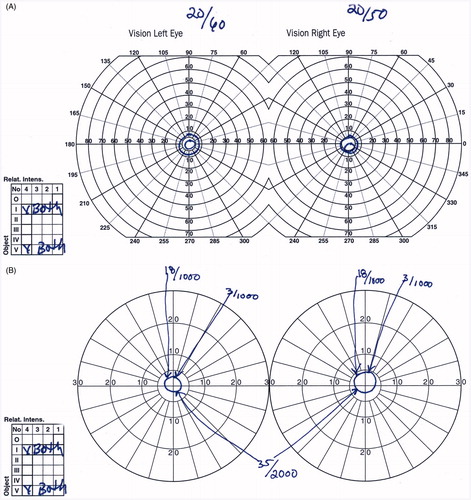

At presentation to our institution, the patient's symptoms encompassed loss of peripheral vision, poor night vision, diplopia, word aphasia, tremors, myoclonus, and weight loss (70 pounds in 1.5 years) with decreased appetite. In addition, she exhibited several side effects of immunosuppression and malnutrition, including Candida esophagitis, chronic fatigue, and gingival hemorrhage. Rheumatological evaluation was negative for lupus, among other immunological diseases, and a repeat anti-retinal antibody titer was within normal range. During ophthalmic evaluation, the patient was noted to ambulate extraordinarily well for having a 10-degree visual field (). Further investigation revealed inconsistencies in vision deficit from previous visual field tests. Near and distant visual field screening subsequently revealed absence of normal expansion of visual field at distance (). ERG done under careful guidance starting with the left eye, because of her claustrophobia, also showed no abnormalities. Furthermore, careful examination of the ERG done elsewhere showed that the diagnosis of scotopic diminution in the left eye was the result of averaging multiple discordant, poorly obtained waveforms. The lack of visual field expansion (keyhole fields) together with negative anti-retinal antibodies titers and ERG findings confirmed our suspicion of psychogenic vision loss.

FIGURE 1. (A) Goldmann manual visual field test. The patient's visual field is centrally constricted (keyhole field) at less than 10 degrees. A keyhole field leads to difficulty maneuvering around objects in the periphery in organic vision loss. (B) Tangent screen test. The visual field remained consistent when the size of the object, as well as the distance between the patient and the tangent screen, was increased (3/1000 = object of 3 cm in size at 1 m distance from the patient; 18/1000 = 18 cm object at 1 m; 35/2000 = 35 cm object at 2 m).

Functional vision loss makes up 1% of the referrals to ophthalmologists, with the highest incidence in young females.Citation1,Citation2 It is defined as vision loss without evidence of organic pathology. In the absence of malingering and factitious disorder, functional vision loss is referred to as psychogenic vision loss (PVL), which is a somatoform disorder caused by increased psychological susceptibility to suggestion. Depending on the origin of the suggestive force, each presentation of PVL encompasses a unique constellation of nonpathognomonic symptoms. It is important to note that the patient's visual decline along with manifestation of systemic symptoms were due to genuine belief in the accuracy of her false-positive anti-retinal antibody lab test.

In the modern medical realm, screening for critical disease such as cancer and autoimmune disorders has led to reduction in adverse events.Citation3,Citation4 However, tests with incorrect results have significant ramifications. For instance, false-positive mammograms can lead to anxiety, psychosomatic pain, and long-term psychosocial consequences.Citation5 False-positive in utero testing and early neonate testing have resulted in pregnancy termination and/or stigmatization of the child.Citation6,Citation7 In low resource settings, false-positive HIV tests have led to breastfeeding cessation, putting infants at increased risk for mortality.Citation8

The detection of anti-retinal antibodies has led to an association of anti-retinal antibodies to autoimmune retinopathies, which encompass paraneoplasticCitation9–12 and nonparaneoplasticCitation13 syndromes. The test detects antibodies that primarily affect photoreceptor function and can lead to progressive visual decline. However, there is dissent in the use of anti-retinal antibodies as a diagnostic tool. First, anti-retinal antibodies can be nonspecific, presenting in 42% of people without ocular disease.Citation14 Furthermore, Western blot for anti-retinal antibodies is imprecise, exhibiting roughly a 64% concordance rate between laboratories using the same detection protocol.Citation15 Thus, clinical vigilance by the medical professional is imperative in accurate diagnosis of autoimmune retinopathy, and the results have to be used in the context of clinical, electroretinographic, perimetric, and imaging data that truly is compatible with autoimmune retinopathy.

In conclusion, anti-retinal antibodies can be positive in the absence of clinical disease. False-positive tests may affect the patient psychologically and lead to clinical decline. Care must be taken in patients with positive anti-retinal antibodies to ensure the presence of definitive disease before initiation of treatment.

Declaration of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

References

- Lim SA, Siatkowski RM, Farris BK. Functional visual loss in adults and children patient characteristics, management, and outcomes. Ophthalmology. 2005;112:1821–1828

- Bose S, Kupersmith MJ. Neuro-ophthalmologic presentations of functional visual disorders. Neurol Clin. 1995;13:321–339

- Tria Tirona M. Breast cancer screening update. Am Fam Physician. 2013;87:274–278

- Vansteenkiste J, Dooms C, Mascaux C, et al. Screening and early detection of lung cancer. Ann Oncol. 2012;23:320–327

- Brodersen J, Siersma VD. Long-term psychosocial consequences of false-positive screening mammography. Ann Fam Med. 2013;11:106–115

- Hansen D, Dehlholm B. [Psychosocial consequences of screening programs in children]. Nord Med. 1992;107:280–282

- Tluczek A, Orland KM, Cavanagh L. Psychosocial consequences of false-positive newborn screens for cystic fibrosis. Qual Health Res. 2011;21:174–186

- Lamberti LM, Fischer Walker CL, Noiman A, et al. Breastfeeding and the risk for diarrhea morbidity and mortality. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:S15

- Adamus G, Brown L, Schiffman J, et al. Diversity in autoimmunity against retinal, neuronal, and axonal antigens in acquired neuro-retinopathy. J Ophthalmic Inflamm Infect. 2011;1:111–121

- Carboni G, Forma G, Bond AD, et al. Bilateral paraneoplastic optic neuropathy and unilateral retinal compromise in association with prostate cancer: a differential diagnostic challenge in a patient with unexplained visual loss. Doc Ophthalmol. 2012;125:63–70

- Luiz JE, Lee AG, Keltner JL, et al. Paraneoplastic optic neuropathy and autoantibody production in small-cell carcinoma of the lung. J Neuroophthalmol. 1998;18:178–181

- Weleber RG, Watzke RC, Shults WT, et al. Clinical and electrophysiologic characterization of paraneoplastic and autoimmune retinopathies associated with antienolase antibodies. Am J Ophthalmol. 2005;139:780–794

- Morohoshi K, Ohbayashi M, Patel N, et al. Identification of anti-retinal antibodies in patients with age-related macular degeneration. Exp Mol Pathol. 2012;93:193–199

- Ko AC, Brinton JP, Mahajan VB, et al. Seroreactivity against aqueous-soluble and detergent-soluble retinal proteins in posterior uveitis. Arch Ophthalmol. 2011;129:415–420

- Faez S, Loewenstein J, Sobrin L. Concordance of antiretinal antibody testing results between laboratories in autoimmune retinopathy. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2013;131:113–115