We would like to report a complex case of ocular leishmaniasis. A 38-year old West-African patient with a history of HIV and cutaneous leishmaniasis caused by Leishmania major presented with a conjunctival nodule. Direct microscopic evaluation of a conjunctival biopsy revealed Leishmania amastigotes. Real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) on the conjunctival biopsy, performed at the reference laboratory of the Institute of Tropical Medicine, targeting a 115-bp sequence of the 18S rRNA gene of Leishmania spp., aided in the diagnosis of conjunctival and disseminated cutaneous leishmaniasis. A positive control (L. donovani, 0.1 pg/µL) and negative water control were run together with the samples to control the amplification process. A real-time PCR targeting the human beta-globine gene was used to control the DNA extraction efficiency. The cutaneous manifestations consisted of multiple small nonulcerating nodules on hands, arms, and face, as well as an ulcer on the right leg. Medical history was significant for HIV (treated with ritonavir, atazanavir, lamivudine, and abacavir, CD4 count: 140 (11.5%) and viral load (<400 copies/mL) at the time of conjunctival biopsy, large B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma (in remission after 5 courses of CHOP), and pancytopenia with positive PCR for CMV treated with ganciclovir. Clinical improvement was seen on a systemic regimen of meglumine antimoniate (Glucantime, Sanofi-Aventis, France) 850 mg daily. Despite the improvement, this was discontinued due to a drug-induced pancreatitis. The treatment was completed with liposomal amphotericin (AmbiSome, Gilead, California) 150 mg, once weekly.

Two years later the patient presented with severe photophobia, discomfort, and blurred vision. Visual acuity was 0.5 (0.8 with pinhole) in the right eye (RE) and 0.64 (no improvement with pinhole) in the left eye (LE). CD4 count was at 312 (10%) and viral load at <20 copies/mL under antiretroviral therapy. Biomicroscopy showed bilateral superficial punctate keratitis, extensive stromal infiltration, granulomatous keratic precipitates, aqueous cells, and flare. The conjunctiva was hyperemic with a marked ciliary flush and pterygia. Posterior segment showed no abnormalities. The diagnosis of a granulomatous anterior uveitis was made and topical therapy with fluorometholone and hyaluronic acid-based artificial tears was initiated. Symptoms and vision improved with a visual acuity of 1.0 (RE) and 0.5 (LE).

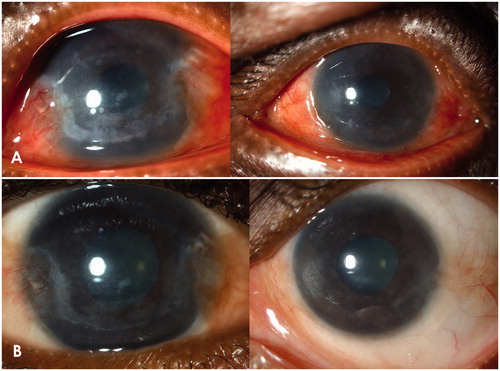

Two months later, the patient returned with a severe recurrence of the anterior uveitis with intense photophobia and pain in both eyes. Visual acuity was counting fingers bilaterally. Slit-lamp examination revealed an increase in granulomatous keratic precipitates, cells, and flare, hypopyon in RE, corneal edema, marked ciliary flush, and conjunctival hyperemia. Intraocular pressure was within the normal range bilaterally. A regimen of hourly prednisolone acetate and atropine sulfate three times daily was started. Initial symptomatic improvement was followed by recurrences and a diminishing response to corticosteroids. The granulomatous keratic precipitates increased in size and number and were accompanied by a pigmented pseudo-hypopyon and progression in stromal infiltrates (). A modest rise in intraocular pressure was also detected.

Figure 1. (A) both eyes before treatment. (B) both eyes 3 months after local treatment with amphotericin B.

Due to the unsatisfactory clinical response, a corneal scrape and an anterior chamber tap were performed. Leishmania PCR was positive on both samples. Due to small sample size, no direct microscopy was performed. The long-term systemic treatment had no effect on the corneal and anterior chamber disease; therefore, an alternative means of administering the antimicrobial treatment was required.

Intrastromal and intracameral injections of 0.1 mL amphotericin B (7.5 µg/0.1 mL) were performed in both eyes with a 3-week interval between the eyes. BCVA on the day of injection was 0.125 RE and 0.16 LE.

Two months postinjection, stromal infiltrates were notably diminished with no signs of active inflammation (). VA was 1.0 in RE and 0.63 in LE. Five months after clinical resolution, the patient presented again with a severe bilateral panophthalmitis and severely reduced visual acuity. Samples for microbial investigation were obtained from cornea, aqueous, and vitreous. Bacterial, mycobacterial, viral, and fungal cultures remained negative, as did PCR for TB. Leishmania PCR was persistently positive, indicating presence of Leishmania DNA in the tissue, so treatment with intraocular amphotericin and systemic miltefosine (Impavido, Aeterna Zentaris, Canada) 50 mg twice daily was repeated. After 3 weeks, inflammation decreased and BCVA partly recovered to 0.2 RE and 0.6 LE.

Leishmania is a protozoan hemoflagellate, which is transmitted by sandflies.Citation1,Citation2 Leishmaniasis may present in cutaneous, mucosal, or visceral forms. Disseminated disease may also be accompanied by local foci of leishmaniasis. The variety of disease manifestations is also accompanied by a wide spectrum of healing responses. Localized cutaneous leishmaniasis may heal spontaneously in immunocompetent individuals, though mucosal, visceral, and disseminated cutaneous disease typically requires treatment. Immunosuppression, such as HIV co-infection, may distort the clinical picture with atypical presentations and is often prone to relapses.Citation2

Reports of ophthalmic leishmaniasis in humans are rare. The most frequent ocular manifestation is cutaneous eyelid disease,Citation3 though there are a few reports of conjunctival disease, fulminant anterior uveitis, and posterior uveitis.Citation4,Citation5 The anterior uveitis caused by Leishmania is granulomatous in natureCitation4,Citation5 and, despite intensive systemic treatment, there is a high degree of ocular morbidity with many cases resulting in blindness.Citation6 A review of the literature identified only two reports of Leishmania-related corneal disease, dating from 1942 and 1979.Citation7,Citation8 The corneal manifestations were described very accurately, making direct comparison with this case possible. Furthermore, in the article by de Andrade,Citation7 the author implied that Leishmania-related keratitis occurred relatively frequently. The absence of reports on ophthalmic-related leishmaniasis in present-day literature may be due to underreporting, as leishmaniasis is still a neglected disease.

In this case of complex ocular leishmaniasis, the patient presented initially with cutaneous and conjunctival lesions. His presentation 2 years later was due to corneal opacities and granulomatous uveitis of unknown etiology. Onchocerciasis was considered in the differential diagnosis, but no microfilaria were seen and serology was negative. Only after a positive aqueous and corneal PCR could a diagnosis of ocular leishmaniasis be definitively made.

The first-line systemic treatment of leishmaniasis is with pentavalent antimonials, administered parenterally as a daily regimen. More recently, however, treatments with liposomal amphotericin B and miltefosine (Impavido) have been used with good effect.Citation9 The initial systemic treatment in this case was highly complicated and commenced with meglumine antimoniate (Glucantime), which was changed to amphotericin B because of drug-induced pancreatitis. Subsequent renal failure necessitated a change to miltefosine, followed by a successful return to meglumine antimoniate after another episode of renal failure.

Although systemic treatment of the initial cutaneous and conjunctival manifestation was effective, it showed no effect on the subsequent corneal and anterior chamber manifestations. It was therefore essential to consider a more effective local treatment. As mentioned previously, amphotericin B has activity against LeishmaniaCitation9 and a history of safe use in ophthalmic practice. Intracameral and intrastromal amphotericin have been used to treat fungal keratitis and endophthalmitis, though this approach has not been described in leishmanial keratouveitis.Citation10–12 Qu et al. compared the aqueous and corneal concentrations of amphotericin B in a rabbit model using three modes of administration: topical, intrastromal, and intracameral.Citation13 Intrastromal injection resulted in effective intracorneal drug levels for a period of 7 days, but did not result in a sufficiently high aqueous concentration. Intracameral injection was the only of the three modes of administration that reached high aqueous levels, though not lasting for more than 24 h. There is one report of leishmanial panuveitis treated with an intravitreal injection of amphotericin B, resulting in clinical improvement, but keratitis was not present in this case.Citation14 Topical administration was not a viable option due to the poor penetration of the drug into the cornea.

This is the first report where the ocular presence of the parasite has been proven in vivo using modern diagnostic tools such as PCR testing on aqueous and corneal samples. The corneal infiltrative lesions and anterior segment inflammation did not respond to systemic Leishmania treatment. This case is also the first report of a good clinical response to an intrastromal and intracameral amphotericin B approach in ocular leishmaniasis. The patient is currently clinically stable, though the long-term effect and possible need for further treatment is not yet known.

Declaration of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

References

- Murray HW, Berman JD, Davies, CR, et al. Advances in leishmaniasis. Lancet. 2005;366:1561–1577

- Goto H, Lindoso JAL. Current diagnosis and treatment of cutaneous and mucocutaneous leishmaniasis. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2010;8:419–433

- Veraldi S, Bottini S, Currò N, et al. Leishmaniasis of the eyelid mimicking an infundibular cyst and review of the literature on ocular leishmaniasis. Int J Infect Dis. 2010;14S:e230–e232

- Blanche P, Gombert B, Rivoal O, et al. Uveitis due to Leishmania major as part of HAART-induced immune restitution syndrome in a patient with AIDS. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34:1279–1280

- Meenken C, van Aegtmael MA, ten Kate RW, et al. Fulminant ocular leishmaniasis in an HIV1-positive patient. AIDS. 2004;18:1485–1486

- Ramos A, Cruz I, Muñez E, et al. Post-Kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis and uveitis in an HIV-positive patient. Infection. 2008;36:184–186

- De Andrade C. Interstitial and ulcerous keratitis in leishmaniasis. Arch Ophthalmol. 1942;27:1193–1198

- Roizenblatt J. Interstitial keratitis caused by American (mucocutaneous) leishmaniasis. Am J Ophthalmol. 1979;87:175–179

- Frézard F, Demichelli C. New delivery strategies for the old pentavalent antimonial drugs. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2010;7:1343–1358

- Kaushik S, Ram J, Brar GS, et al. Intracameral amphotericin B: initial experience in severe keratomycosis. Cornea. 2001;20:715–719

- Yoon KC, Jeong IY, Im SK, et al. Therapeutic effect of intracameral amphotericin B injection in the treatment of fungal keratitis. Cornea. 2007;26:814–818

- Garcia-Valenzuela E, Song D. Intracorneal injection of amphotericin B for recurrent fungal keratitis and endophtalmitis. Arch Ophthalmol. 2005;123:1721–1723

- Qu L, Li L, Xie H. Corneal and aqueous humor concentrations of amphotericin B using three different routes of administration in a rabbit model. Ophthalmic Res. 2010;43:153–158

- Gontijo CMF, Pacheco RS, Oréfice F, et al. Concurrent cutaneous, visceral and ocular leishmaniasis caused by Leishmania (Vianna) Braziliensis in a kidney transplant patient. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2002;97:751–753