A patient with bilateral granulomatous uveitis also had the simultaneous manifestation of granulomatous inflammation under red dye areas of a 10-year-old multicolored tattoo. The patient manifested secondary cystoid macular edema and uveitic glaucoma due to the chronic uveitis. Punch biopsy of the inflamed area of the tattooed dermis displayed a dense lichenoid granulomatous inflammation. Thoracic imaging revealed lymphadenopathy and pulmonary biopsy confirmed a diagnosis of sarcoidosis.

This case and review of literature demonstrates that tattoo inflammation, whether generalized or localized to a particular color, should be considered a potential sign of systemic sarcoidosis and patients should be carefully evaluated for systemic granulomatous inflammation.

Case Report

A 44-year-old African American male veteran presented with complaints of bilateral ocular pain, photophobia, and blurred vision. The 10-year-old tattoo on his left arm was “thick and scaly” for the same 2-month period. He had received a 0.5-mL IM influenza vaccination (Sanofi Pasteur) in his right deltoid 2 months prior to his initial clinical presentation and at the approximate time of the initiation of his symptoms. His medical history was positive for arthritis and mild chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and he denied any previous ocular injuries or surgeries. He was not using any significant systemic medication and denied any drug allergies. He denied cigarette, alcohol, and illicit drug use. He reported his maternal grandmother had glaucoma. Review of systems was positive for chest pain and shortness of breath.

Best corrected visual acuities were 20/150 in the right eye (OD) and 20/150 in the left eye (OS). Slit-lamp evaluation revealed trace injection of the bulbar conjunctiva along with 4+ anterior chamber cells and 2+ flare in both eyes (OU) according to the SUN grading scheme. There were multiple keratic precipitates and a near complete posterior iris synechiae OU. Fundus examination revealed a healthy appearing optic nerve OD with a 0.35 cup-to-disc ratio without edema or pallor. The optic nerve OS had a glaucomatous appearance with a 0.75 cup-to disc-ratio without edema or pallor. Intraocular pressure (IOP) was 14 mmHg OD and 16 mmHg OS. The optic nerves and retinal nerve fiber layer were analyzed with a time-domain Stratus optical coherence tomography (OCT) revealing healthy, robust nerve tissue OD of average thickness 108.27μm, but thinning inferiorly and superiorly OS with average thickness 70.23 μm, indicative for probable glaucoma OS with more testing necessary.

An aggressive dosing of topical prednisolone acetate 1% and atropine 1% was prescribed and a standard granulomatous uveitis blood panel was ordered. All results returned unremarkable with the exception of an elevated angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE). A chest x-ray (CXR) followed by a more detailed thoracic computed tomography (TCT) was also performed to explore for pulmonary disease. A consultation was placed to both dermatology and pulmonology departments. The refractory ocular inflammation resulted in bilateral cystoid macular edema (CME) 6 months following the patient's initial presentation. The maculae were scanned with retinal time-domain Stratus OCT to reveal a foveal thickness of 514 μm OD and 409 μm OS. The patient was referred to the ophthalmology clinic for triamcinolone intraocular injections.

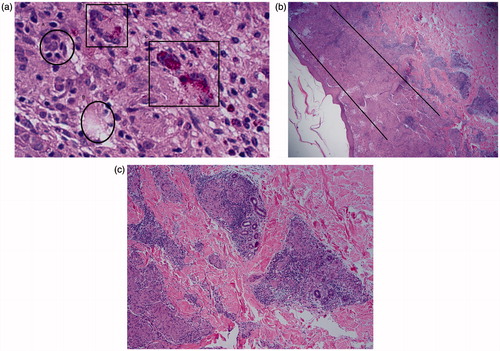

The tattoo on the patient's left brachium contained indurated plaques sharply limited to red dye of the tattoo while the black dye was completely uninvolved (). An 8-mm punch biopsy of the tattoo revealed a “dense lichenoid granulomatous inflammation permeating the superficial, mid, and deep dermis along with eccrine units.” The inflammation consisted of foci of reddish brown pigment, histiocytes, and multinucleated giant cells (). There was no evidence of infection or necrosis. Infrared spectroscopy confirmed large, red, birefringent particles within the dermis containing carbon and consistent with “an aromatic, organic, non-mercury-containing dye within the cytoplasm of the macrophages and multinucleated giant cells.” The aromatic dye could not be further specified among several hundred possible chemical sources, as the red dye spectra were not identical to previous cases or to the reference spectra of the department of environmental and toxicologic pathology, but was consistent with red dye tattoo ink. Unfortunately, the tattoo artist was also unable to be contacted in regard to the composition of the dye. Following the results of the cutaneous biopsy, the patient was given an intralesional injection of triamcinolone.

CXR and TCT revealed lymphadenopathy of the middle mediastinum along with both right and left hila. Pulmonary function testing (PFT) was performed and compared to measurements from 2 years prior revealing mild restriction. An endobronchial ultrasound guided transbronchial needle aspiration (EBUS-TBNA) and bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) were performed. The specimen from the biopsy of the patient's right lower lobe lymph node contained mononuclear cells along with a trace amount of squamous cells and polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMNs). There were small, well-formed granulomas with accompanying lymphocytes. Acid-fast bacillus and periodic acid Schiff stains failed to reveal any acid-fast or fungal organism and there was no evidence of tissue necrosis. Flow cytometry revealed no distinct CD34+ population. Approximately 74% of the cells were within the lymphoid gate, 48% of which were T cells and 45% of which were B cells, the high lymphocyte percentage being indicative of sarcoidosis. There was no aberrant T-cell antigen or light chain restriction. There was no abnormal CD19/5+, CD19/10+, or CD38/138+ populations identified, where mutations may be indicative of severe immunodepression. No features were diagnostic for malignancy. Importantly, no birefringent tattoo particles were found within the specimen. The EBUS-TNA and BAL results confirmed a diagnosis of sarcoidosis, and 20 mg daily oral prednisolone was prescribed and eventually tapered. His ongoing pulmonary symptoms are now managed only with steroidal and bronchodilator inhalers.

The timeline of the inflammatory reaction following the patient's influenza vaccination raised suspicion of an activation of his immune system from allergy of the injected material. The Sanofi Pasteur influenza vaccination the patient received was preserved with thimerosal. Thimerosal is a mercury-containing preservative and is frequently an ingredient of red tattoo dye, especially at the time of application of the patient's tattoo. As a precaution, mercury-containing substances were added to the patient's allergy list and the patient was warned of a potential thimerosal allergy.

Comment

Scar sarcoidosis is a granulomatous infiltration and elevation of previously flat scars. In addition to previous injury sites, scar sarcoidosis has been documented in tattoos and in sites of previous intramuscular injections, blood donation, and herpes zoster.Citation1 The first case of tattoo sarcoidosis was mentioned by MaddenCitation2 in 1939. Granulomatous inflammation under scars is believed to occur due to systemic or local diseases as a result of being sites of lower resistence.Citation3 Scar sarcoidosis is an example of the well-known Koebner phenomenon, which is defined as skin lesions appearing on lines of trauma. The Koebner phenomenon was first mentioned in 1877 as psoriatic lesions appearing on scars and no other location in psoriatic patients.Citation4

Immunological granulomatous reactions are often indistinguishable from foreign body granulomatous reactions, with the exception of the presence of the foreign matter. Although foreign body granulomas are generally, by definition, isolated to the offending foreign body, there have been documented cases of foreign matter resulting in systemic granulomatous inflammation.Citation5 Many studies have found incidental birefrigent material within the cutaneous biopsies of patients with known systemic sarcoidosis.Citation5–6 Foreign bodies have also been found in granulomatous systemic lesions. These studies demonstrate that foreign bodies may be a stimulus for granuloma formation in some cases of sarcoidosis.

There have been a number of documented cases of granulomatous tattoo inflammation confined to a specific color dye in cases of sarcoidosis with only a cutaneous component. There are far fewer reports of tattoo reaction confined to a particular color dye along with systemic inflammation (). Inflammation restricted to a particular color dye is evidence that a local hypersensitivity is the origin to a broad, sarcoid-like systemic inflammation. Sensitization in delayed hypersensitivity inflammation can actually occur at any point during the existence of the foreign body antigen. Therefore, tattoo reactions may occur weeks to years following placement of the tattoo.

Table 1. Review of literature.

Although reactions to red,Citation7–16 purple,Citation17–18 green,Citation19 blue,Citation20–24 brown,Citation25 and blackCitation16,Citation26–28 have been reported, mercuric sulfide (red pigment) is the most common irritant in tattoo hypersensitivity.Citation2,Citation7–10 Modern red pigment alternatives such as cadmium selenide (cadmium red), ferric hydrate (sienna/red ochre), and organic vegetable dyes such as brazilwood and sandalwood are still causing red dye hypersensitivities.Citation2,Citation10 Documented reactions to red tattoo dye include dermatitis of granulomatous, lichenoid, and pseudolymphomatous types ().

There have been a number of documented cases of uveitis associated with a granulomatous tattoo reaction (). Saliba et al.Citation28 reported a case of bilateral panuveitis and CME associated with a non-color-specific tattoo reaction and a cutaneous biopsy that revealed noncaseating granulomas. The patient was diagnosed as having delayed tattoo hypersensitivity on account of serum ACE, chest x-ray, and CT scan all being normal. No pulmonary biopsy was performed on account of the normal imaging; however, the patient was symptomatic with a chronic cough and had a history positive for asthma. The patient was successfully treated with systemic immunosuppressive agents.

Hanada et al.Citation7 documented 3 cases of bilateral uveitis, BHL, and red dye-specific tattoo noncaseating granulomatous inflammation. However, aluminum, mercury, and silicon were found within the bronchial biopsy specimen. Lubeck et al.Citation3 described a case of BHL, polyarthralgia, a nonspecific red, blue, and green tattoo nonnecrotizing granulomatous inflammation with simultaneous bilateral uveitis, which increased in severity and led to bilateral glaucoma. The patient was treated with systemic corticosteroids, which suppressed the inflammation. Post et al.Citation31 described a case of granulomatous inflammation in a monochromatic tattoo, bilateral uveitis with suggestive pulmonary changes. The patient in the Post et al.Citation31 case was given a diagnosis of sarcoidosis, but pulmonary biopsy was not performed.

Moschos et al.Citation32 reported a case of severe posterior uveitis with retinal vasculitis and CME following tattoo placement, which resolved after systemic immunosuppressive therapy. Their systemic workup ruled out an infectious or autoimmune cause and the severe vasculitis was concluded to be the result of severe tattoo hypersensitivity. Mansour et al.Citation33 described a case of chronic bilateral uveitis with recurrent simultaneous swelling of various tattoo sites preceding the ocular inflammation by 1 week. Results of laboratory, imaging, and lung biopsies were repeatedly negative. The high B-lymphocyte and macrophage ratio with an equal number of T-helper and T-suppressor cells was demonstrative of a delayed hypersensitivity reaction and not of a typical sarcoidosis histology. An elevation T-helper cells is typical in traditional sarcoidal inflammation.

Our case is unique on account of the confinement of the inflammation only within the red dye tattoo areas in the multicolored tattoo in addition to the other multisystem involvement. The limitation to the red areas indicates that this is more than the previously described Koebner phenomenon. If our case were simply a case of severe delayed tattoo dye hypersensitivity as in the Hanada et al.Citation7 cases, then we would expect foreign birefringent particles to be present not only in the cutaneous punch biopsy, but also in EBUS-TNA and BAL specimens. We suspect that the sarcoidal reaction in this case was the result of an immunologic cascade to the foreign red-dye tattoo antigen. Since the specific red dye was not recognizable or reproducible in our case, patch testing was not performed, although the majority of patch tests previously performed on red dye tattoo hypersensitivity have been inconclusive. Due to the 10-year delay between the placement of the tattoo and the initiation of symptoms, we believe an immunological trigger set off the systemic inflammation. As previously mentioned, the patient in our case received his influenza vaccine 2 months prior to his first presentation in our clinic and the approximate time his tattoo signs appeared. His triggering event may very well have been his viral vaccination leading to the stimulation of his immune system. Our patient was injected with 0.5 mL im influenza vaccination (Sanofi Pasteur) preserved with thimerosal, an organomercury compound.

Handler et al.Citation34 reported a case of granulomatous inflammation confined to the blue areas of a patient's tattoo 1 week following injection of an H1N1 vaccine containing 0.01% thimerosal preservative. The injection was administered directly superior to the tattoo on the right deltoid, which was placed 8 years prior. The patient underwent a sarcoidosis workup that was unremarkable with exception of a moderate restrictive lung defect on PFT. Handler et al.Citation34 theorized the release of the tattoo pigment into extracellular space during the patient's immunization initiated the granulomatous reaction. The Handler et al.Citation34 case differs from our case because our patient received his vaccination in the arm contralateral to the tattooed arm. Therefore, the theory of Handler et al. of the release of the tattoo pigment would not apply to our case. We believe our patient developed a hypersensitivity to mercury and the injection of the vaccination with the mercuric compound caused a systemic hypersensitivity simply by the injection of the organomercury compound.

In our case, there were no signs of mercury in the birefringence investigation of the biopsied tattoo pigment. However, we strongly believe there was mercury contained in the original red compound, on account of the popularity of the ingredient in red tattoo dye, even though the tattoo biopsy was negative for mercury within the pigment granules in the inflammatory cells' cytoplasm. Taaffee and WyattCitation35 reported a case of a lichenoid reaction confined to red areas of a 14-year-old tattoo in a metallurgy extraction process worker. Although no mercury was identified in the biopsy of the patient's tattoo, the authors believed mercury was in fact used in the red dye as mercury was commonly used when the patient's tattoo was applied.

To our knowledge, this is the first documented case of bronchoscopy-confirmed systemic sarcoidosis presenting with an aggressive bilateral granulomatous uveitis and resulting subsequent CME and glaucoma, BHL, and color-specific granulomatous tattoo inflammation. The finding of a granulomatous tattoo inflammation restricted to a specific color dye should not be assumed to be strictly a localized hypersensitivity reaction and warrants an extensive workup for systemic sarcoidosis, including chest imaging and possible bronchoscopy confirmation, a comprehensive ophthalmological examination, and close monitoring if tests fail to reveal the disease. Tissue samples should also be carefully examined with stains for bacterial, fungal, and mycobacterial infection, while malignancy must also be ruled out as a cause of the inflammation. The isolation of inflammation to a particular tattoo color in the presence of systemic sarcoidosis supports the theory of an exogenous antigen releasing an inflammatory cascade leading to the disease. Risk of secondary multisystem sarcoidosis should be included in possible side effects of tattooing and there should be an increase in public awareness. This case demonstrates that widespread sarcoidal inflammation may result from a hypersensitivity to an identifiable antigen.

Declaration of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

References

- Hong YC, Na DJ, Han SH, et al. A case of scar sarcoidosis. Korean J Intern Med. 2008;23:213–215

- Madden JF. Reactions in tattoos, chronic discoid lupus erythematosus. Arch Derm Syphilol. 1949;60:789–793

- Lubeck G, Epstein E. Complications of tattooing. Calif Med. 1952;76:83–85

- Köbner H. Zur Aetiologie Ppsoriasis. Vjschr Dermatol. 1876;3:559

- Kim YC, Triffet MK, Gibson LE. Foreign bodies in sarcoidosis. Am J Dermatopathol. 2000;22:408–412

- Marcoval J, Mañá J, Moreno A, et al. Foreign bodies in granulomatous cutaneous lesions of patients with systemic sarcoidosis. Arch Dermatol. 2001;137:427–430

- Hanada K, Chiyoya S, Katabira Y. Systemic sarcoidal reaction in tattoo. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1985;10:479–484

- Sowden JM, Cartwright PH, Smith AG, et al. Sarcoidosis presenting with a granulomatous reaction confined to red tattoos. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1992;17:446–448

- Cruz FAM, Lage D, Frigério RM, et al. Reactions to the different pigments in tattoos: a report of two cases. An Bras Dermatol. 2010;85:708–711

- Mortimer NJ, Chave TA, Johnston GA. Red tattoo reactions. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2003;28:508–510

- Wollina U, Gruner M, Schönlebe J. Granulomatous tattoo reaction and erythema nodosum in a young woman: common cause or coincidence? J Cosmet Dermatol. 2008;7:84–88

- Verdich J. Granulomatous reaction in a red tattoo. Acta Derm Venereol. 1981;61:176–177

- Kluger N, Godenèche J, Vermeulen C. Granuloma annulare within the red dye of a tattoo. J Dermatol. 2012;39:191–193

- Barabasi Z, Kiss E, Balaton G, Vajo Z. Cutaneous granuloma and uveitis caused by a tattoo. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2008;120:1--2

- Bagley MP, Schwartz RA, Lambert WC. Hyperplastic reaction developing within a tattoo: granulomatous tattoo reaction, probably to mercuric sulfide (cinnabar). Arch Dermatol. 1987;123:1557, 1560–1561

- Tope WD, Arbiser JL, Duncan LM. Black tattoo reaction: the peacock's tale. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;35:477–479

- McFadden N, Lyberg T, Hensten-Pettersen A. Aluminum-induced granulomas in a tattoo. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989;20:903–908

- Schwartz RA, Mathias CG, Miller CH, et al. Granulomatous reaction to purple tattoo pigment. Contact Derm. 1987;16:198–202

- Loewenthal LJ. Reactions in green tatoos: the significance of the valence state of chromium. Arch Dermatol. 1960;82:237–243

- Rorsman H, Brehmer-Andersson E, Dahlquist I, et al. Tattoo granuloma and uveitis. Lancet. 1969;2:27–28

- Collins P, Evans AT, Gray W, Levison DA. Pulmonary sarcoidosis presenting as a granulomatous tattoo reaction. Br J Dermatol. 1994;130:658–662

- Yoong C, Vun YY, Spelman L, Muir J. True blue football fan: tattoo reaction confined to blue pigment. Australas J Dermatol. 2010;51:21–22

- Haddad C, Webb FJ, Haddad-Lacle J. Delayed complication from a tattoo. Am Fam Physician. 2012;86:669–670

- Bachmeyer C, Blum L, Petitjean B, et al. Granulomatous tattoo reaction in a patient treated with etanercept. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2007;21:550–552

- Ali SM, Gilliam AC, Brodell RT. Sarcoidosis appearing in a tattoo. J Cutan Med Surg. 2008;12:43–48

- Baumgartner M, Feldmann R, Breier F, Steiner A. Sarcoidal granulomas in a cosmetic tattoo in association with pulmonary sarcoidosis. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2010;8:900–902

- Jones MS, Maloney ME, Helm KF. Systemic sarcoidosis presenting in the black dye of a tattoo. Cutis. 1997;59:113–115

- Saliba N, Owen ME, Beare N. Tattoo-associated uveitis. Eye (Lond). 2010;24:1406

- Anolik R, Mandal R, Franks AG Jr. Sarcoidal tattoo granuloma. Dermatol. Online J. 2010;16:19

- Morales-Callaghan AM Jr, Aguilar-Bernier M Jr, Martínez-García G, Miranda-Romero A. Sarcoid granuloma on black tattoo. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:S71–S73

- Post J, Hull P. Tattoo reactions as a sign of sarcoidosis. CMAJ. 2012;184:432

- Moschos MM, Guex-Crosier Y. Retinal vasculitis and cystoid macular edema after body tattooing: a case report. Klin Monbl Augenheilkd. 2004;221:424–426

- Mansour AM, Chan CC. Recurrent uveitis preceded by swelling of skin tattoos. Am J Ophthalmol. 1991;111:515–516

- Handler M, Tonkovic-Capin V, Brewster S, et al. Granulomatous reaction confined to two blue-ink tattoos after H1N1 influenza vaccine. J Vaccines Vaccin. 1:108. doi:10.4172/2157-7560.1000108

- Taaffe A, Wyatt EH. The red tattoo and lichen planus. Int J Dermatol. 1980;19:394–396

- McElvanney AM, Sherriff SM. Uveitis and skin tattoos. Eye (Lond). 1994;8:602–603

- Jones B, Oh C, Egan CA. Spontaneous resolution of a delayed granulomatous reaction to cosmetic tattoo. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:59–60

- Toulemonde A, Quereux G, Dréno B. Sarcoidosis granuloma on a tattoo induced by interferon alpha. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2004;131:49–51

- Atluri D, Iduru S, Veluru C, Mullen K. A levitating tattoo in a hepatitis C patient on treatment. Liver Int. 2010;30:583–584