Corneal infiltrates are a relatively uncommon complication after refractive surgery. Infectious corneal infiltrates may result in a significant loss of vision. Diffuse lamellar keratitis (DLK) is one of the most common sterile inflammations after LASIK. Recent studies have documented the clinical course of peripheral necrotizing keratitis following femtosecond-LASIK.Citation1,Citation2 We report the first case of bilateral peripheral necrotizing keratitis following femtosecond-LASIK using a high-frequency, low-energy VisuMax femtosecond laser system.

Case Report

A 29-year-old woman presented to our clinic on February 26, 2013. She had unremarkable medical and ocular histories except for an 8-year history of soft contact lens wear. The tear-film breakup time was 6 seconds, and the Schirmer's test scores were 11 mm in both eyes. Slit-lamp examination showed no evidence of meibomian gland dysfunction or chronic blepharitis. Preoperatively, the uncorrected visual acuity (UCVA) was 20/200 in both eyes; the best corrected visual acuity (BCVA) was 20/20 with a manifest refraction of −4.25–0.25 × 165 in the right eye and −3.75–0.50 × 20 in the left eye. The corneal topography did not reveal any abnormality. Informed consent for the procedure was obtained.

Uneventful bilateral femtosecond-LASIK was performed on February 28, 2013 by an experienced surgeon. A VisuMax femtosecond laser system (Carl Zeiss Meditec) with a 500-kHz repetition rate was used for flap creation. The flap thickness was 85 µm. A Mel 80 Excimer Laser (Carl Zeiss Meditec) was used for stromal ablation. Prednisolone acetate, neomycin sulfate, and polymyxin sulfate eyedrops (Poly-Pred, Allergan) were applied topically upon completion of the procedure.

The patient had no subjective complaints the day after surgery. The UCVA was 20/20 in both eyes. The corneas and flaps were clear under slit-lamp examination. Topical fluorometholone (FML) 0.1% ophthalmic solution, levofloxacin drops, and carboxymethylcellulose sodium eyedrops were prescribed 4 times a day.

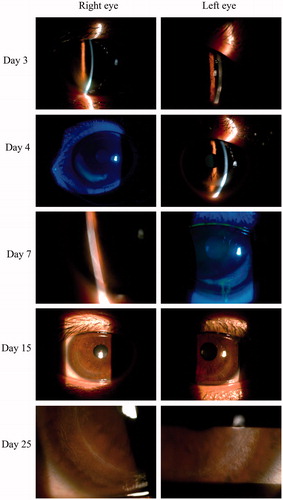

Three days after surgery, the patient presented complaining of photophobia and nighttime eye pain in both eyes. A slit-lamp examination of the right eye revealed a white confluent stromal infiltrate peripheral to the flap edge, with an irregular epithelium from 5 o'clock to 9 o'clock, and a clear zone between the limbus and the infiltrate. An examination of the left eye showed some solitary, discrete infiltrates at 5 O'clock along the flap edge, and an intact epithelium (, day 3). Based on the clinical evidence of bilateral, circumferential, and peripheral location without conjunctival injection, a diagnosis of noninfective keratitis was made. Therefore, the flaps were not lifted for corneal scrapings and culture. Topical FML was used every 2 h instead of 4 times a day.

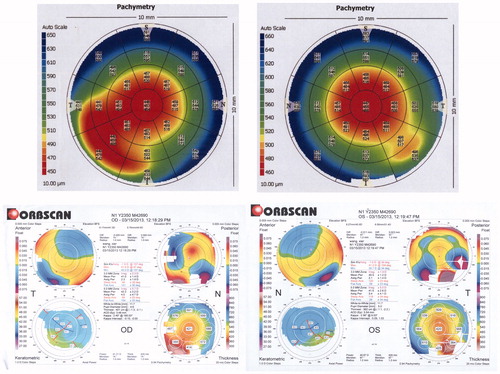

FIGURE 1. (A) Slit-lamp photography of the evolution process of cornea infiltrates of both eyes. (B) AS-OCT and corneal topography examination revealed inferior cornea stromal thinning.

On day 4, the eye pain and photophobia had been relieved. An examination revealed progressive worsening of the corneal infiltration in the left eye. A confluent stromal infiltrate was observed, similar to that in the right eye. In the right eye, there was no extension of the stromal infiltrate, but the overlying epithelium at the edge of the flap was damaged, indicated by positive staining with fluorescein dye (, day 4). A 3-day course of methylprednisolone (200 mg iv every day) was administered to treat the worsening corneal infiltration and stromal necrosis.

On day 7, both eyes had improved and there was increased transparency and no further extension or stromal infiltrates. The overlying epithelium had not healed completely, and necrotizing and ulceration were seen with fluorescein dye (, day 7). Oral methylprednisolone (32 mg) was prescribed once a day for 1 week, tapering by 8 mg a week thereafter. The patient complained of blurred vision in her right eye. UCVA was 20/30 in the right eye and 20/20 in the left eye. BCVA was 20/20 in both eyes. The manifest refractions were −0.5–1.00 × 130 in the right eye and −0.25–0.50 × 25 in the left eye.

On day 15, the stromal opacities were seen in both eyes, but the transparency had increased further along the flap edge (, day 15). Anterior segment optical coherence tomography (AS-OCT) (Carl Zeiss Meditec, Germany) and corneal topography (Orbscan II, Bausch & Lomb, USA) examinations revealed inferior cornea stromal thinning and an increase in the curvature of the inferior cornea compared to other areas (). On day 25, the inflammation resulted in mild residual stromal scarring in the areas of the ulceration in both eyes (, day 25). The manifest refractions were −0.25–1.00 × 125 and −0.50 × 25 in the right and left eyes. The patient still complained of blurred vision in her right eye, with a BCVA of 20/20 in both eyes and UCVA of 20/30 in her right eye.

Discussion

This case demonstrated a peripheral sterile keratitis in which the corneal infiltrates were well defined and straddled the edge of the flap with overlying necrotizing of the epithelium and ulceration, induced by an uneventful femtosecond-LASIK treatment in a patient with no systemic diseases.

Several reports have described sterile corneal infiltrates after corneal refractive surgery. Teal et al.Citation3 were the first authors to describe corneal subepithelial infiltrates following photorefractive keratectomy (PRK) in 1995. In 2005, Lifshitz et al.Citation4 first reported a case of peripheral sterile corneal infiltrate after LASIK using a 60-kHz IntraLase FS (femtosecond) Laser. In 2012, Bucci and McCormickCitation1 described a case of necrotizing peripheral keratitis after LASIK, using a low-energy (<100-nJ), high-frequency (1000-kHz) Femto LDV femtosecond laser. Here, we report a case of bilateral necrotizing peripheral keratitis after LASIK using a high-frequency (500 kHz), low-energy (130-nJ) VisuMax femtosecond laser for flap creation. Furthermore, we provide evidences of cornea thinning after infiltration by AS-OCT and corneal topographic examinations.

The exact mechanism of the formation of peripheral sterile corneal infiltrates after refractive surgery is unknown. In the previous study, it was suggested that the sterile infiltrate was related to the use of topical nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) without concomitant use of topical steroids,Citation3,Citation5 immunologic reaction,Citation6 and topical anesthetic abuse.Citation7 However, no NSAIDs were administered to the patient either preoperatively or postoperatively in our case. Our observation is inclined to support other etiologies of staphylococcal-immune infiltrates.Citation6 In addition, sterile peripheral keratitis has been reported in patients with chronic meibomian gland dysfunction and chronic blepharitis,Citation8,Citation9 as well as systemic inflammatory and autoimmune diseases. Lahners et al.Citation8 reported on a patient with known rheumatoid arthritis, who developed bilateral infiltrates after LASIK to the right eye only, demonstrating that surgery in just one eye can trigger an immune reaction in both eyes. Carp et al.Citation10 described a case of necrotizing keratitis that developed after LASIK in a patient with inflammatory bowel disease. The potential initiating events for an immunologic reaction include the deposition of immune complexes, serum autoantibodies, vasculitic injury, aberrant expression of HLA-II antigens on corneal epithelium and keratocytes, or an aberrant cell-mediated response to corneal injury.Citation8 We summarized the patient characteristics and treatments in the cases that have been published so far of sterile infiltration after LASIK (). We observed that some patients had histories of chronic blepharitis and meibomian gland dysfunction, while others had autoimmune diseases. Most patients underwent treatments of intensive topical antibiotic and corticosteroid eyedrops to control the inflammation, and others required systemic medications.

TABLE 1. The characteristics and treatment of patients with corneal infiltration after LASIKCitation1,Citation2,Citation4,Citation8–15.

There was no known medical history of autoimmune disorders, chronic blepharitis, or meibomian gland disease in our case. The linear, circumferential orientation of the infiltrates and crescent shape along the flap edge helped us rule out a diagnosis of infectious keratitis. We also did not lift the flap to obtain cultures or perform irrigation with balanced salt solution and steroids. The previous study recommended that if sterile infiltrates were diagnosed, invasive investigations, such as lifting the flap and performing corneal scrapings, should be avoided to prevent potential complications from aggressive interventions. The creation of epithelial defects may predispose the eye to the development of epithelial ingrowths and DLK.Citation1

In our case, the inflammation did not respond well to intensive topical steroid treatment. However, the systemic administration of steroids on the following day did prevent worsening of the inflammation. Although the inflammation was controlled by the correct diagnosis and treatment, the necrosis and infiltration of the corneal tissue still resulted in stromal thinning and affected the UCVA. In 2 of the 3 cases reported by Lifshitz et al., oral steroids were administered and tapered over 2 weeks with good responses.Citation4 We also recommended systemic administration of steroids when the inflammation was unresponsive to intensive topical steroid therapy.

In conclusion, we first presented a case with necrotizing sterile peripheral keratitis after LASIK performed with a VisuMax femtosecond laser. It is critical to differentiate sterile peripheral keratitis from infectious keratitis because the management is very different. A clear understanding of this disease and administration of the correct treatment may help to control the inflammation promptly, thus avoiding potential harm to visual acuity.

Declaration of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

References

- Bucci MG, McCormick GJ. Idiopathic peripheral necrotizing keratitis after femtosecond laser in situ keratomileusis. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2012;38:544–547

- Aman-Ullah M, Gimbel HV, Purba MK, et al. Necrotizing keratitis after laser refractive surgery in patients with inactive inflammatory bowel disease. Case Rep Ophthalmol. 2012;3:54–60

- Teal P, Breslin C, Arshinoff S, et al. Corneal subepithelial infiltrates following Excimer Laser photorefractive keratectomy. J Cataract Refract Surg. 1995;21:516–518

- Lifshitz T, Levy J, Mahler O, et al. Peripheral sterile corneal infiltrates after refractive surgery. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2005;31:1392–1395

- Arshinoff SA, Mills MD, Haber S. Pharmacotherapy of photorefractive keratectomy. J Cataract Refract Surg. 1996;22:1037–1044

- Rao SK, Fogla R, Rajagopal R, et al. Bilateral corneal infiltrates after Excimer Laser photorefractive keratectomy. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2000;26:456–459

- Kim JY, Choi YS, Lee JH. Keratitis from corneal anesthetic abuse after photorefractive keratectomy. J Cataract Refract Surg. 1997;23:447–449

- Lahners WJ, Hardten DR, Lindstrom RL. Peripheral keratitis following laser in situ keratomileusis. J Refract Surg. 2003;19:671–675

- Ambrósio R Jr, Periman LM, Netto MV, et al. Bilateral marginal sterile infiltrates and diffuse lamellar keratitis after laser in situ keratomileusis. J Refract Surg. 2003;19:154–158

- Carp GI, Verhamme T, Gobbe M, et al. Surgically induced corneal necrotizing keratitis following LASIK in a patient with inflammatory bowel disease. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2010;36:1786–1789

- Yu EYW, Rao SK, Cheng ACK, et al. Bilateral peripheral corneal infiltrates after simultaneous myopic laser in situ keratomileusis. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2002;28:891–894

- Solomon JD, Weigel J, Holzman AE. Peripheral keratitis following low-pulse energy femtosecond laser in situ keratomileusis. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2012;38:1881–1882

- Haw WW, Manche EE. Sterile peripheral keratitis following laser in situ keratomileusis. J Refract Surg. 1999;15:61–63

- Moon SW, Kim YH, Lee SC, et al. Bilateral peripheral infiltrative keratitis after LASIK. Korean J Ophthalmol. 2007;21:172–174

- Singhal S, Sridhar MS, Garg P. Bilateral peripheral infiltrative keratitis after LASIK. J Refract Surg. 2005;21:402–404