Abstract

Introduction: Since Jean-Nicolas Marjolin reported carcinoma arising in post-traumatic scars in 1828, the term ‘Marjolin ulcer’ has been applied to malignant changes in burn scars. Although many papers have been published already in this field, there are few reports from Oriental people. Methods: From 1989 to 2008, there were 11 cases noted as burn scar carcinoma in Chang Gung Memorial Hospital. Ten were reported as squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) and the one was verrucous carcinoma. Most of the cases occurred in the extremities (10/11). Results: Ten cases underwent an operation initially with wide excision and skin graft or local flap for coverage. Forefoot amputation was performed in one patient. One patient received above-knee amputation and adjuvant therapy because recurrent verrucous carcinoma occurred 2 years later. One patient suffered from a new lesion 8 years later and another case had inguinal lymph node metastasis 8 months later. Five patients were lost to follow-up and six cases were tumor-free during the follow-up period. Most scar malignancies are SCC while other cell types are rarer. Conclusion: The casual association between burn injuries and a later risk of basal cell carcinoma is questionable. Owing to poor prognosis in advanced scar cancer, the best treatment for scar carcinoma is to prevent the scar from developing repeated ulceration by performing aggressive initial burn wound care: early grafting by surgeons and daily scar care with regular follow-up for patients. This may be why a lower incidence has been noted in recent years.

Key words::

Introduction

Malignancies arising in burn scars were described in the first century AD by Celsus. Marjolin, in 1828, defined chronic ulcers originating from scar tissues. However, Da Costa, in 1903, invented the term ‘Marjolin's ulcer’ to describe malignant change of skin scars, especially burns (Citation1). Most burn scar carcinomas are the squamous cell type (more than 75%); however, basal cell carcinoma (BCC) (about 12%) has been reported (Citation2). The average latency period from injury to onset of malignancy is 31 years (Citation2). The lower extremities were most frequently affected (more than 40%). Poor prognosis compared with conventional skin cancer is another characteristic due to the high rate of recurrence (16%), lymph node metastasis (22%), distant metastasis (14%), and mortality (21%) (Citation2). Treatment of scar carcinoma continues to be controversial. In this paper, we present our experience of burn scar carcinoma.

Materials and methods

From 1988 to 2008, a total of 11 cases of burn scar carcinoma were treated in Chang Gung Memorial Hospital. There were five male and six female patients. The age at diagnosis ranged from 22 to 63 years (average 47 years). The mean interval from time of the burn to appearance of the cancer was 27.3 years. All of their burn wounds, except one, were allowed to heal by secondary intension. All experienced long-term recurrent ulceration. The joint region was the most commonly involved site, including three in the popliteal area, one on the ankle, one in the axilla, and two on the elbow. There was no lymphadenopathy on presentation ().

Table I. Data from 11 cases of burn scar carcinoma.

Results

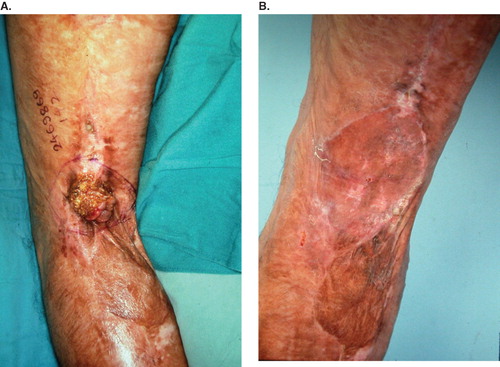

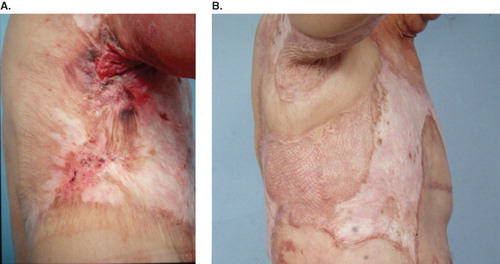

All cases received wide excision with a safe margin of at least 2 cm away from the tumors. Nine patients were then treated with skin graft for wound coverage. Combined skin grafting and local flap for large wound coverage was performed in two cases (). One case underwent forefoot amputation due to local deep invasion. The pathologic type was predominantly squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) in 10 patients and verrucous carcinoma in one case. All section margins were free of malignancy. Local recurrence and inguinal lymphadenopathy developed in the case with verrucous carcinoma 2 years postoperatively (). AK amputation, lymph node dissection and adjuvant chemotherapy were done in 1999. Another female patient developed inguinal lymph node metastases with no sign of local recurrence 8 months later. She received lymph node dissection in 2006. One case whose previous lesion was in the popliteal area suffered from a new lesion on the ipsilateral upper thigh 8 years later (). He received wide excision and skin grafting in 2006. Five patients were lost to follow-up and six cases remained tumor-free during the follow-up period ().

Figure 1. (A) Burn scar cancer at the axilla; (B) after wide excision and local flap and skin grafting. Tumor-free for 7 years to present.

Discussion

Incidence

The incidence of BCC is one to four per 1000 (Citation3), more than that of SCC. About 80% of all skin cancers are BCC, 16% are SCC, and 4% are melanoma (Citation2). In contrast, SCC is the most frequent burn scar neoplasm and the second is BCC. This is a reversal of incidence of these two tumors in burn scar cancers compared to their occurrence in the general population. It is estimated that 2% of burn scars undergo malignant transformation in the past (Citation4). What is the data today? One would expect to see fewer cases of burn scar neoplasms since the current standard of care requires early grafting and regular scar care. From 1989 to 2007, a total of 9531 patients were treated in our burn center; 10 years later, the latency period, we can estimate the incidence of malignant change of burn scars.

Sex

There were no differences in sex distribution in our series. However, the incidence in males was predominant; about 62% reviewed from the literature (Citation2). Even so, the fact that men have a greater tendency toward burn scar carcinoma is a wrong inference. This male predominance probably occurs because more males are burned (70% of burned patients are male in our burn center).

Anatomic location

Anatomically there is a preponderance of carcinomas on the extremities, especially the lower extremities. Burn scar cancer is typically seen on the lower extremities (43.7%), upper extremities (22.4%), trunk (11.5%) and head (22.4%) (Citation5). There is a propensity for burn scar cancer to arise in the flexion crease of the limbs: popliteal space, elbow, or groin area (Citation4,Citation6). In our series, the joint region was the most commonly involved site (seven patients, 63.6%). This is because repeated ulceration easily occurred at the joint area due to daily activities.

Pathological cell type

SCC is the most common cell type in burn scar carcinoma. A total of 71% of the burn scar tumors were SCC, 12% were BCC, and 6% were melanoma (Citation2). Sarcoma is rare. The burn scar SCC is clearly a distinct entity from that of conventional skin SCC and tends to be more aggressive in nature. The average age of onset is in the fifth decade of life, younger than that of the conventional SCC. In contrast to spontaneously occurring SCC, most of which arises on the head and neck (90%), 60% of burn scar SCC are typically seen on the extremities (Citation5). The average period is 10 years from premalignant lesion to onset of SCC; however, the lag period of burn scar SCC is about 30 years. The recurrence, metastasis, and mortality rates are quite different (). The majority of burn scar carcinomas occur in burns that have not been grafted. It may arise from chronic ulceration of burn wounds. Forty to fifty percent of the patients were reported with long-term ulceration (Citation7–9). The long-standing epidermal hyperplasia and increased mitotic activity at the edges of these chronic wounds may increase the risk of malignant transformation. The other 50% of patients without chronic ulceration had burn scar cancers. The pathophysiology may differ from that mentioned above. The relatively avascular scar tissue and no lymphatic channels in scars may then act as an immunologically privileged site that allows the tumor to resist the body's usual defenses (Citation10,Citation11). At the molecular level, Harland et al. and Sakatani et al. reported on the abnormalities in the p53 gene in patients with burn scar carcinoma (Citation12,Citation13). Lee had shown that burn scar SCC cases have Fas gene mutations in the apoptosis function region (Citation14). All our cases experienced long-term recurrent ulceration and the pathologic type was predominantly SCC. Marjolin's ulcer in the form of verrucous carcinoma, one variant of SCC, is rarely seen.

Table II. Comparison between conventional SCC with burn scar SCC.

Are the burn scar BCC different from conventional skin BCC? BCC usually occurs in lesions where the sweat glands and hair follicles have not been destroyed, such as superficially burned scars or when the burned area is small. So BCC should not originate from deep burn scar ulceration. Many of the burn scar neoplasms occurred in deeper burns; they no longer had the basal cells available in the burn area unless they had been skin-grafted. Whether BCC are related to stable burn scar is questionable. Most reported basal cell carcinomas occurring on burn scars are located in the head and neck area. The general characteristics of burn scar BCC are nearly the same as conventional BCC (). Burn scar BCC were least likely to have lymph node or distant metastases and had the lowest mortality (less than 1%) – the same as conventional BCC (Citation2). BCC are stroma-dependent, and experimentally transplanted BCC, free of dermal tissue, do not survive (Citation15). Approximately 2% of burn scars undergo malignant change over time (Citation4). Therefore, the incidence of BCC in burn scar is about 2.4 per 1000 burned patients (2% × 12%), which is not more than that of BCC in the normal population. We can presume that there is no casual association between burn injuries and a later risk of BCC.

Table III. Comparison between conventional BCC with burn scar BCC.

Prognostic factor

High histological grade, tumor location – especially on the lower extremities, large tumor diameter (> 10 cm), and regional lymphadenopathy on presentation are poor prognostic factors. Acute type, location on the head, neck, or upper limbs, exophytic form, well differentiated grade, peritumoral T-lymphocyte infiltration and absent metastasis on presentation are a better prognosis (Citation5). Even though the huge verrucous carcinoma is a well-differentiated SCC, local recurrence occurred 2 years later in our series. The tumor size may play a more important role than differentiated grade.

Prevention of the burn scar cancer

Promotion of rapid epithelization and early grafting are the principles of treating initial burns. Malignant degeneration rarely develops in a primarily grafted burn, although exceptions have been reported because areas of primary graft failure or where pinch grafts were used also show an increased likelihood of developing burn scar carcinoma (Citation16). Post-burn scar contracture should be relieved to prevent breakdown of the scar.

Treatment

Wide excisions including Mohs micrographic surgery with margin control must be done. Without nodal involvement, chances of a surgical cure can be favorable. Skin grafting with a full-thickness skin graft is favored for coverage of a joint area, with flap coverage 1 year later to ensure that recurrence is not obscured. If there is lymph node metastasis, then wide excision, lymph node dissection, radiotherapy (Citation7), and chemotherapy are indicated. Some authors believe that prophylactic lymph node dissection is necessary in all Marjolin's ulcer patients. Sentinel lymph node biopsy is another choice. Eastman et al. emphasized that sentinel lymph node biopsy identifies occult nodal metastases in patients with Marjolin's ulcer (Citation17). It is a minimally invasive and accurate staging procedure. Positive nodes in four patients out of six were identified when lymph nodes were clinically absent in those patients (Citation17). Bostwick et al. advocates that node dissection be done 2–4 weeks following surgery of a large tumor (Citation18).

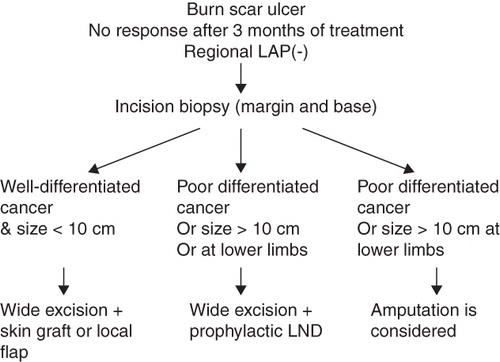

In Eser's series, the patients with advanced disease (the diameter of the tumor is over 10 cm) all died even after combined therapy (Citation19). So radical surgery, prophylactic lymph dissection and adjuvant therapies are likely to be effective only prior to the development of an advanced scar cancer. Amputation and elective lymph node dissection should be suggested given a dire prognosis, as mentioned above, or joint space, bone, extensive local tissue, and major nerve and vessel involvement. In a retrospective review of our case with verrucous carcinoma, which is capable of local invasion and extension into bone, amputation may be needed initially, especially with a large tumor size. The treatment algorithm is presented as .

Recurrence and metastasis

The local recurrence rate of scar cancer is around 10.8–37.0% (Citation2) more than usual SCC (1.3–18.7% (Citation20)). Metastases occur primarily through regional lymph nodes at around 22% (5.6–60%), which is significantly higher than that of usual SCC (0.5–16% (Citation21)) (). Novick and Gard showed an overall incidence rate of metastasis of 34.8% and a higher incidence of metastasis of 53.8% from lower extremity lesions (Citation22). Eroglu and Camlibel studied 107 patients and found that recurrence developed in 22 (30%) of 73 patients treated with wide local excision (Citation23). However, usual SCC on the extremities metastasize in 2–5%; on the face in 10–20% (Citation24). The tumor grows slowly despite its aggressive behavior, but patients may frequently have systemic metastases after wide excision. This may be because occult nodal micrometastases present or scar tissue acts as a barrier to the tumor. When the scar is removed, the tumor may rapidly spread (Citation18). In our series, there was one recurrence, two lymph node metastases and one new lesion. So excision with a safe margin is important and sentinel lymph node biopsy may be helpful.

Prognosis and mortality

The mortality rate of conventional SCC is about 1% (Citation25); however, that of scar cancer is 21–38% (Citation2) (). The mean period of death after scar cancer diagnosis was 25 months (Citation2). The 5-year survival rate varies from 52% to 80%. Edwards mentioned that the median survival of patients with regional adenopathy was 16 months and those without adenopathy was 66 months (Citation26). The mortality rate reported in recent decades is as high as the one studied by Treves and Pack in 1930 (28.5%) (Citation4). This means the optimal treatment of burn scar carcinoma remains unclear.

Conclusion

Burn injuries may not have a casual association with a later risk of BCC. This needs review of previous reports and further investigations. Incision biopsy should be taken for suspected Marjolin's ulcer. If the pathology shows well-differentiated SCC without distant metastasis or regional lymphadenopathy, then safe excision margin and skin graft coverage are adequate. A full-thickness skin graft or flap should be used for coverage of the flexion crease of the extremities. If there is lymphadenopathy on presentation, lymph node dissection must be done. If the tumor is poorly differentiated or its size is greater than 10 cm, especially if located on the lower extremities, then prophylactic lymph node dissection may be indicated. Because of poor prognosis in advanced scar cancer, prevention is the best treatment, with initial early grafting for a deep burn wound and proper scar care. Studies at the molecular level of scar cancer may help us in the early detection or treatment of scar cancer in the future.

Declaration of interest: The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the article.

References

- Da Costa JC. Carcinomatous changes in an area of chronic ulceration, or Marjolin's ulcer. Ann Surg. 1903;37:496–502.

- Kowal-Vern A, Criswell BK. Burn scar neoplasms: A literature review and statistical analysis. Burns. 2005;31:403–413.

- Miller DL, Weinstock MA. Nonmelanoma skin cancer in the United States: Incidence. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;30:774–778.

- Treves N, Pack GT. Development of cancer in burn scars. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1930;51:749–782.

- Tania J. Burn scar carcinoma diagnosis and management. Dermatol Surg. 1998;22:561–565.

- Arons MS, Lynch JB. Scar tissue carcinoma: I. A clinical study with special reference to burn scar carcinoma. Ann Surg. 1965;161:170–188.

- Ozek C, Cankayali R, Bilkay U, Guner U, Gundogan H, Songur E, . Marjolin's ulcers arising in burn scars. J Burn Care Rehabil. 2001;22:384–389.

- Chowdri NA, Darzi MA. Postburn scar carcinomas in Kashmiris. Burns. 1996;22:477–482.

- Lawrence EA. Carcinoma arising in the scars of thermal burns. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1952;95:579–588.

- Futrell JW, Myers GH Jr. The burn scar as an ‘immunologically privileged site’. Surg Forum. 1972;23:129–131.

- Dellon AL, Potvin C, Chretien PB, Rogentine CN. The immunobiology of skin cancer. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1975;55:341–354.

- Harland DL, Robinson WA, Franklin WA. Deletion of the p53 gene in a patient with aggressive burn scar carcinoma. J Trauma. 1997;42:104–107.

- Sakatani S, Kusakabe H, Kiyokane K, Suzuki K. p53 gene mutations in squamous cell carcinoma occurring in scars: Comparison with p53 protein immunoreactivity. Am J Dermatopathol. 1998;20:463–467.

- Lee SH, Shin MS, Kim HS. Somatic mutations of Fas (Apo-1/CD95) gene in cutaneous cell carcinomas arising from a burn scar. J Invest Dermatol. 2000;114:122–126.

- Miller SJ. Biology of basal cell carcinoma (Part I). J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;24:1–13.

- Türegün M, Nisanci M, Güler M. Burn scar carcinoma with longer lag period arising in previously grafted area. Burns. 1997;23:496–497.

- Eastman AL, Erdman WA, Lindberg GM, Hunt JL, Purdue GF, Fleming JB. Sentinel lymph node biopsy identifies occult nodal metastases in patients with Marjolin's ulcer. J Burn Care Rehabil. 2004;25:241–245.

- Bostwick J, Pendergrast WJ, Vasconez LO. Marjolin's ulcer: An immunologically privileged tumor? Plast Reconstr Surg. 1976;57:66–69.

- Eser A, Serkan Y, Tayfun A. Is surgery an effective and adequate treatment in advanced Marjolin's ulcer? Burns. 2005;31:421–431.

- Rowe DE, Carroll RJ, Day CL Jr. Prognostic factors for local recurrence, metastasis, and survival rates in squamous cell carcinoma of the skin, ear, and lip. Implications for treatment modality selection. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;26:976–990.

- Strom SS, Yamamura Y. Epidemiology of nonmelanoma skin cancer. Clin Plast Surg. 1997;24:627–636.

- Novick M, Gard DA, Hardy SB, Spira M. Burn scar carcinoma: A review and analysis of 46 cases. J Trauma. 1977;17:809–817.

- Eroglu A, Camlibel S. Risk factors for locoregional recurrence of scar carcinoma. Br J Surg. 1997;84:1744–1746.

- Roth JJ, Granick MS. Squamous cell and adnexal carcinomas of the skin. Clin Plast Surg. 1997;24:687–703.

- Jensen AO, Olesen AB. Do incident and new subsequent cases of non-melanoma skin cancer registered in a Danish prospective cohort study have different 10-year mortality? Cancer Detect Prev. 2007;31:352–358.

- Edwards MJ, Hirsch RM, Broadwater JR, Netscher DT, Ames FC. Squamous cell carcinoma arising in previously burned or irradiated skin. Arch Surg. 1989;124:115–117.