Abstract

Background: The objective of this study was to evaluate the measurement properties of the Psoriasis Symptom Inventory (PSI), an eight-item patient-reported outcome measure for assessing severity of plaque psoriasis symptoms. Methods: In this prospective, randomized study using data from adults with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis, patients completed the PSI, Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI), SF-36v2 Acute, and Patient Global Assessment (PtGA). PSI construct validity was assessed using Spearman rank correlations between PSI and DLQI and SF-36; test-retest reliability and sensitivity to change were evaluated using PtGA as an anchor. Daily 24-h and weekly 7-day PSI versions were evaluated. Results: Eight US sites enrolled 143 patients; 139 (97.2%) completed the study. All symptoms (itch, redness, scaling, burning, cracking, stinging, flaking, and pain) were reported across all response options (not at all severe, mild, moderate, severe, very severe). Test-retest reliability was acceptable (intraclass correlation coefficients range = 0.70–0.80). A priori hypotheses of convergent and discriminant validity were confirmed by correlations of PSI with DLQI items and SF-36 domains. The PSI demonstrated good construct validity and was sensitive to within-subject change (p < 0.0001). Conclusions: The PSI is brief, valid, reproducible, and responsive to change and has the potential to be a useful PRO measure in psoriasis clinical trials.

Introduction

Psoriasis severity is frequently evaluated in clinical trials using the Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI), the Physician's Global Assessment, and an estimate of the body surface area (BSA) affected by psoriasis (Citation1–3). In addition to clinical measures, patient-reported outcomes (PROs) are important to understand the patient's perspective of disease (Citation4,5). Most PROs used in clinical trials of psoriasis therapies, such as the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) (Citation6) and Short Form 36 v2 Acute Health Survey (SF-36v2), assess the impact of psoriasis or illness in general on health-related quality of life. In patients with psoriasis, PROs often correlate poorly with clinical outcomes as measured by dermatologists (Citation5), indicating that the clinical assessments and PROs measure different aspects of psoriasis.

The Psoriasis Symptom Inventory (PSI) was developed as a patient-reported measure of psoriasis symptoms (Citation7–10). In qualitative studies (Citation7,9), the severity of psoriasis symptoms was shown to be the most relevant and important attribute when patients assessed symptoms associated with their psoriasis (Citation10). The PSI was first drafted to capture daily symptoms including itch from psoriasis, redness of skin, scaling, burning, stinging, cracking, flaking, and pain using a 24-h recall version. As psoriasis is marked by periods of improvement and relapse, a 7-day recall version of the PSI was also developed to capture changes in symptoms over a 1-week period based on input from patients during cognitive interviews indicating that some patients did not report fluctuating symptoms on a day-to-day basis (Citation8,10). The primary objective of this study was to conduct a preliminary assessment of the measurement and psychometric properties of the 24-h PSI with a secondary objective comparing the equivalence of responses to the 24-h and 7-day recall versions.

Methods

Study design

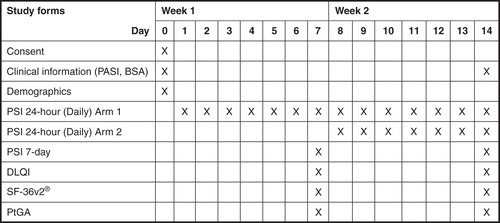

This prospective, randomized, double-arm, study was conducted over a period of 14 days. Clinical measures (PASI and psoriasis-affected BSA) were assessed at baseline and on Day 14 (). On days 7 and 14, patients completed PRO measures including the DLQI, the SF-36v2, and self-reported change using a Patient Global Assessment (PtGA) (Citation6,11).

Patients

Adult patients with psoriasis (≥18 years) with PASI score ≥10 and psoriasis-affected BSA ≥10% were eligible to participate in the study. Patients were required to be potential candidates for systemic therapy or phototherapy for their psoriasis. Patients could not have any medical condition or receive any treatments that would affect their memory, or participate in another study that included the use of investigational or approved medications for psoriasis. Patients could not have plans to initiate a systemic or biologic therapy for psoriasis during the study period.

PSI

The PSI contained eight items (symptom severity concepts) addressing itch from psoriasis, and redness, scaling, burning, cracking, stinging, flaking, and pain of psoriasis lesions. The mean of the seven daily responses for the eight symptom items was calculated to derive a weekly average for that symptom; a minimum of five completed days of the PSI 24-h recall were necessary to derive a weekly score (1–2 missed days, consecutive or nonconsecutive, were allowed). Each item was scored on a 5-point scale based on response: 0 = not at all severe, 1 = mild, 2 = moderate, 3 = severe, and 4 = very severe. Individual scores were summed for a total score, which ranged from 0 to 32. Psoriasis symptom items were the same between daily and weekly versions. For the 7-day recall diary, a sample of item structure was: “Overall, during the last 7 days, how severe was the redness of your skin lesions?” and for the 24-h daily diary, a sample of item structure was: “Overall, during the last 24 h, how severe was the redness of your skin lesions?”

Analytic methods

Sample size and validation analyses.

A minimum sample of 128 participants was calculated to provide at least 80% power to detect a mean difference of 0.3 on PSI items. One-week test-retest reliability was assessed using intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) on the weekly average PSI item scores of Week 1 (mean of days 1–7) and Week 2 (mean of days 8–14). The retest population was defined as patients whose psoriasis and treatment remained stable during the study period (Overall change item = “No Change” and Change in psoriasis treatment = “No”). Minimum values for reliability were predefined as >0.70 (Citation12). Convergent validity was evaluated using prespecified correlations between items and domains from the DLQI and SF-36v2 that are conceptually similar to the individual PSI symptom constructs. Spearman rank coefficients were computed between each PSI item and the DLQI items. Pearson's correlation coefficients were computed between each PSI item and the SF-36v2 domains. Minimum values for validity were predefined as convergent r ≥ 0.30 (Citation13). A stronger association was predefined as a difference in coefficients greater than 0.01 points. Known-groups validity was assessed using baseline DLQI score categories (total scores of 2–10, 11–20, or 21–30); mean PSI item scores and standard deviations (SDs) were calculated for each DLQI category, and one-way analysis of variance was used to compare groups. Ability to detect change was examined using PtGA as anchor; mean PSI total scores and SDs were calculated for patients with PtGA worsening by ≥1 point, no change in PtGA, or improvement in PtGA by ≥1 point, and the F test using repeated measures analysis of covariance (adjusted for body mass index, age, gender, and disease duration) (Citation14) was used to compare groups. Exploratory factor analyses were conducted to examine the measurement model.

Comparison of PSI 24-h and PSI 7-day recall versions.

To assess equivalence between 24-h and 7-day recall versions, the 7-day recall version of the PSI was completed on days 7 and 14 (). Equivalence between the 24-h recall and 7-day recall versions was assessed using bivariate comparisons (t-test) and confirmed using the ICC using data from Week 2 (average weekly scores for days 8–14 for the 24-h version and day 14 for the 7-day version).

As an exploratory analysis, we tested whether 7-day PSI scores were measurably affected by completing the 24-h PSI in the days preceding the 7-day PSI. Patients in one arm completed the 7-day version without first completing the 24-h version and patients in a second arm completed the 7-day version after first completing the 24-h version. Scores from patients in the two arms were compared (controlling for covariates) to identify any potential effect of previous exposure to most recent daily recall on the weekly recall assessment.

Results

Patients

A total of 139 patients from eight sites in the United States completed the study. The mean (SD) age was 51.2 (14.8; range 19–85) years, 56% were men, 91% were white, mean (SD) duration of psoriasis was 18.4 (14.0; range 0–61) years, mean (SD) PASI score at baseline was 17.6 (7.9; range 10.0–50.7), and mean (SD) psoriasis-affected BSA at baseline was 25.4% (17.1%) with a range of 10–75%.

PSI Item scores and characteristics

Mean item scores for Week 1 (days 1–7) and Week 2 (days 8–14) are shown in . Exploratory factor analysis yielded a single factor with coefficients for all items greater than 0.800 and total variance was explained at 71%. The initial performance results showed that all PSI items had acceptable distributions, low missing data, good internal consistency, and acceptable test-retest reliability ().

Table I. PSI item scores.

Table II. PSI item characteristics.

Convergent and known-groups validity

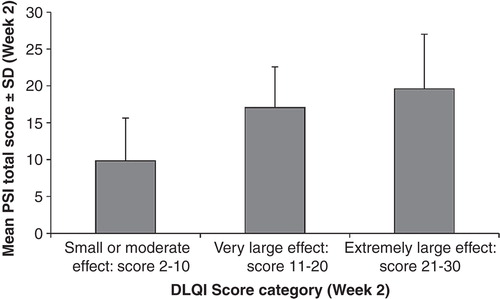

All PSI items were shown to have good convergent validity using Day 14 data (). The highest association between the PSI and the DLQI was seen between item 1 of the DLQI (“How itchy, sore, painful or stinging has your skin been?”) and the PSI total score (Spearman rank r = 0.73; p < 0.001). Items 2 through 9 of the DLQI were also significantly correlated with the PSI total score (p < 0.001). The highest association between the PSI and the SF-36v2 was observed with the bodily pain domain (Pearson's r = –0.59; p < 0.001). Significant correlations between the PSI and the SF-36v2 general health perception, vitality, social function, and mental health domains (p < 0.001) and the physical function, role physical, and role emotional domains (p < 0.01) were observed. Mean (SD) PSI total scores were 9.8 (5.8) for DLQI score 2–10 category; 17.1 (5.5) for DLQI score 11–20 category; and 19.6 (7.4) for DLQI score 21–30 category (f stat = 21.36; p < 0.001) (). PSI item scores were significantly different across DLQI groups (p < 0.001) (data not shown).

Table III. Convergent validity.

Ability of the PSI to detect change

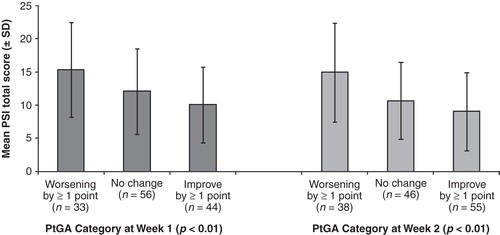

The ability of the PSI to detect change was assessed using categories of PtGA scores and by improvement in PtGA scores. PSI total scores were significantly different, in the expected direction, across categories of change in PtGA (p < 0.01) (). After adjusting for age, sex, body mass index, and duration of psoriasis, in those patients having at least a 1-point improvement in PtGA (n = 44) from Day 0 (PSI least squares mean [LSM] total score = 14.0) to Day 7 (PSI LSM total score = 10.4), the PSI showed significant improvement over time (p < 0.0001). Similar results were found for patients having at least a 1-point improvement in PtGA at Week 2 (n = 55), looking at changes from Day 7 (PSI LSM total score = 11.4) to Day 14 (PSI LSM total score = 9.2) (p < 0.0001).

Figure 3. Ability of the PSI to detect change. Mean PSI total scores for patients with PtGA worsening by ≥1 point, no change in PtGA, or improvement in PtGA by ≥1 point at Week 1 (dark gray bars) and Week 2 (light gray bars) are shown. Error bars represent standard deviations. PSI, Psoriasis Symptom Inventory; PtGA, Patient Global Assessment.

Comparison of PSI 24-h recall and PSI 7-day recall versions

Equivalence was observed between the mean PSI 24-h recall total score (1.39; SD 0.81) and PSI 7-day recall total score (1.41; SD 0.85) (p = 0.465, two-tailed). For all eight items, the ICC was above 0.85 and no differences in mean scores were noted between the PSI 24-h recall (7-day average) and the PSI 7-day recall except for the item “flaking,” which did show a significant difference (p = 0.02, two-tailed), but had an ICC of 0.91 (95% CI: 0.88–0.94) ().

Table IV. Comparison of PSI 24-h recall and PSI 7-day recall.

The scores from patients who did not complete the 24-h version prior to completing the 7-day version (n = 64) did not differ from the scores from patients who did complete the 24-h version prior to the 7-day version (n = 75).

Discussion

The goal of this study was to provide preliminary psychometric evidence evaluating a newly developed PRO measure specific to psoriatic symptoms and to establish its appropriateness for further use in evaluating treatment interventions and observational studies in individuals with psoriasis. Recommended minimum values for reliability (>0.70) (Citation12) and validity (convergent r ≥ 0.30) (Citation13) were exceeded for the PSI. Results of the preliminary exploratory factor analyses indicated that the PSI was unidimensional, and the use of a single score for the PSI was further supported by input from a clinical expert in dermatology. This result is consistent with the use of the model of item and instrument development and strongly supports the use of a brief psoriasis-specific self-report measure that can be administered alongside other clinical measurements in future studies.

Generic measures can be useful for assessments of functional status and other health-related quality of life outcomes and allow for comparison across populations and conditions. In this study, functional status was assessed using the generic SF-36v2, which permits comparison of this population of psoriasis patients with other populations and conditions. Validity of the observed scores obtained from the PSI was confirmed using pre-identified logical relationships between the concepts contained in the new instrument and concepts contained in previously used instruments. We conclude that the PSI is moderately associated with measures of highly similar constructs, including the SF-36v2, a general quality of life, mental and physical well-being instrument, and the DLQI, a psoriasis-specific symptom instrument. Further evidence of known-groups validity was shown () with a significant association (p < 0.0001) between PSI total score and predefined groups of DLQI scores representing small/moderate, very large, and extremely large effects. Building on the content validation evaluated in the qualitative development program (Citation7,9), the results of this analysis support the validity of the PSI and demonstrate that the PSI can be responsive to shorter-term (1 week) improvements in PtGA assessments.

The PSI should provide several advantages when used as a patient-reported assessment of symptom severity. The brevity of the measure should prove attractive in many applications, particularly for use in clinical trials. Further studies are needed to determine the interpretability of the PSI score and to identify the responder definition. Additional studies in the context of treatment trials may allow for testing of the ability for the PSI to detect symptom changes in a study population in response to an intervention.

An additional feature of this study was the concurrent development and equivalence testing of a 7-day weekly recall version of the PSI. The 7-day items mirror the 24-h version with the inclusion of “In the past 7 days….” Our overall findings showed that the two PSI versions yielded equivalent results. Although the actual item scores for “flaking” differed between the 24-h and 7-day versions, the correlation (ICC) between the total scores of the two versions was acceptable. The “flaking” item score was included in the PSI total score, and therefore, item-level differences do not lend sufficient evidence to warrant deletion of the item. Moreover, there was strong qualitative evidence justifying the inclusion of all eight symptom items of the PSI. Thus, both the 24-h PSI and 7-day PSI appear to provide comprehensive capture of symptoms and may be useful in psoriasis observational studies and clinical trials as well as in clinical practice to monitor change in patients' psoriasis symptoms. It is possible that completing the daily PSI in the days preceding the weekly PSI could affect responses to the weekly items resulting in differences in responses between the 24-h recall PSI and 7-day recall PSI; however, the 24-h PSI and 7-day PSI performed similarly, and there was no effect of completing the daily assessment on the responses to the weekly recall PSI.

The results of this study may be generalizable to most patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis based on the broad range of PASI scores (10.0 to 50.7) and psoriasis-affected BSA (10% to 75%) in the study population. The patients in this study represent the typical type of patient who would be appropriate for enrollment in clinical trials of systemic or biologic therapies for psoriasis. Additionally, patients who participated in the study were recruited from all regions of the United States. Although the preponderance of white subjects (91%) is reflective of the population in clinical trials, it may limit the generalizability to non-white races. Further research would be needed before broad adoption in clinical practice. Because this study collected data from patients with relatively stable disease, future studies are needed to confirm the ability of the PSI to detect improvements in symptoms when a patient initiates a new psoriasis therapy.

Assessing psoriatic symptoms from the perspective of the patient provides information not captured by clinician-assessed physiological measures and may provide a window into therapeutic efficacy and symptom control. The results presented here indicate that the PSI is brief, valid, reproducible, and responsive to change, and should be a useful PRO measure in clinical trials and observational studies of patients with psoriasis.

Declaration of interest

This study was funded by Amgen Inc. DMB, MLM, and KM are employees of Health Research Associates, which received funding for this study. KG has received honoraria from and served as a consultant to Abbott Laboratories, Amgen, Janssen Novartis, Pfizer, Merck, and Lilly and has received grants from Abbott, Amgen, Janssen, Lilly, and Celgene. C-FC and XH are past employees and shareholders of Amgen Inc. BO and GK are employees and shareholders of Amgen Inc. Julia R. Gage, PhD, provided writing support on behalf of Amgen Inc. Jon Nilsen, PhD (Amgen Inc.) provided editorial assistance.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dina Chau and Hema N. Viswanathan for comments on an earlier draft.

References

- Spuls PI, Lecluse LL, Poulsen MLBos JD, Stern RS, Nijsten T. How good are clinical severity and outcome measures for psoriasis?: quantitative evaluation in a systematic review. J Invest Dermatol. 2010;130:933–943.

- Fredriksson T, Pettersson U. Severe psoriasis–oral therapy with a new retinoid. Dermatologica. 1978;157:238–244.

- Bonifati C, Berardesca E. Clinical outcome measures of psoriasis. Reumatismo. 2007;59:64–67.

- Marquis P, Arnould B, Acquadro C, Roberts WM. Patient-reported outcomes and health-related quality of life in effectiveness studies: pros and cons. Drug Dev Res. 2006;67:193–201.

- Shikiar R, Bresnahan BW, Stone SP, Shikiar R, Bresnahan BW, Stone SP, Thompson C, Koo J, Revicki DA, et al. Validity and reliability of patient reported outcomes used in psoriasis: results from two randomized clinical trials. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2003;1:53.

- Finlay AY, Khan GK. Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI)–a simple practical measure for routine clinical use. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1994;19:210–216.

- Martin ML, McCarrier K, Chiou C-F, Gordon K, Kimball AB, Van Voorhees AS, Gottlieb AB, Huang X, et al. Development of a new patient reported measure for assessing symptoms of psoriasis. 20th European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology Congress; Lisbon, Portugal; 20–24 October 2011.

- Martin ML, McCarrier K, Bushnell DM, Gordon K, Chiou C-F, Huang X, Ortmeier B, Kricorian G. Validation of the Psoriasis Symptom Inventory (PSI), a patient reported outcome measure. 20th European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology Congress; Lisbon, Portugal; October 20–24 2011.

- Martin ML, McCarrier K, Chiou C-F, Gordon K, Kimball A, Van Voorhees A, Gottlieb AB, Huang Xet al. Development of a new patient reported measure for assessing symptoms of psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66:AB190.

- Martin ML, McCarrier K, Bushnell DM, Gordon K, Chiou C-F, Huang X, Ortmeier B, Kricorian G, et al. Validation of the Psoriasis Symptom Inventory (PSI), a patient-reported outcome measure. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66:AB207.

- Ware JE Jr, Kosinski M, Bjorner JB, Turner-Bowker DM, Gandek B, Maruish MEet al. User's manual for the SF-36v2™ health survey. 2nd edition. Lincoln, RI: QualityMetric Inc, 2007.

- Lohr K. Assessing health status and quality-of-life instruments: attributes and review criteria. Qual Life Res. 2002;11:193–205.

- Cohen J. Statistical power analysis in the behavioral sciences. 2nd edition. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc, 1988.

- Husted J, Thavaneswaran A, Chandran V, Eder L, Rosen CF, Cook RJ, Gladman DD, et al. Cardiovascular and other comorbidities in patients with psoriatic arthritis: a comparison with patients with psoriasis. Arthritis Care Res. 2011; 63: 1729–1735.