Abstract

Purpose: In this manuscript, we evaluated the effectiveness of an intervention programme consisting of integrated care and a participatory workplace intervention on supervisor support, work instability and at-work productivity after 6 months of follow-up among workers with rheumatoid arthritis (RA).

Methods: We conducted a randomized controlled trial; we compared the intervention programme to usual care. Eligible patients were diagnosed with RA, had a paid job (> 8 h per week) and who experienced, at least, minor difficulties in work functioning. Supervisor support was measured with a subscale of the Job Content Questionnaire, work instability with the Work Instability Scale for RA, and at-work productivity with the Work Limitations Questionnaire. Data were analyzed using linear regression analyses.

Results: A beneficial effect of the intervention programme was found on supervisor support among 150 patients. Analyses revealed no effects on work instability and at-work productivity.

Conclusion: We found a small positive effect of the intervention on supervisor support, but did not find any effects on work instability and at-work productivity loss. Future research should establish whether this significant but small increase in supervisor support leads to improved work functioning in the long run. This study shows clinicians that patients with RA are in need of efforts to support them in their work functioning.

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a chronic inflammatory disease with a severe impact on work functioning, even when a patient is still working.

It is important to involve the workplace when an intervention is put in place to support RA patients in their work participation.

Supervisor support influences health outcomes of workers, and it is possible to improve supervisor support by an intervention which involves the workplace and supervisor.

Implications for Rehabilitation

Introduction

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a chronic, systemic autoimmune disease which is characterized by inflammation of the joints and fluctuating symptoms such as pain and fatigue. The disease manifests itself in the synovial membrane of the joint and might result in structural damage to the joint.[Citation1] The medical treatment of RA has improved tremendously over time, and it is nowadays possible to prevent structural, irreversible damage. Patients might be treated with Disease Modifying Anti-Rheumatic Drugs (DMARDs; aim to bring chronic inflammations to a halt), and with biological therapeutics (aim to remove proteins involved in the immune reaction that causes the inflammation). The effectiveness of DMARDs and biological therapeutics on decreasing disease activity has been established.[Citation2,Citation3] Patients experience life with RA along a continuum from RA in the background to RA in the foreground of their lives, and vice versa. Even if RA is put back to the background of patient’s lives by means of disease-modifying agents, most patients still experience continuous, daily symptoms.[Citation4] RA has a profound impact on participation, from daily life activities, to, for example, a person’s working life.[Citation5–7] Despite a slight decrease in work disability (permanent exclusion from work) rates over the past decade, permanent work disability still occurs frequently.[Citation8]

At-work productivity loss implies that a person is present at work, but is limited in meeting work demands. Besides at-work productivity loss, work instability is also an important concept for patients who are still working. Work instability refers to a mismatch between job demands and abilities of the individual. A person with high work instability is at risk of losing his job. Work adaptations can be implemented to reduce work instability. The importance of supervisor support in the wellbeing of workers and the ability to continue working has been shown before. Previous studies suggest that supervisors influence health outcomes of workers. In a systematic review, it was shown that positive leader behaviours (such as support and empowerment) are associated with a low degree of employee stress.[Citation9] Supervisor support is associated with increased productivity,[Citation10] and with lower sickness absence,[Citation11] whereas low supervisor support is associated with increased long-term sick leave.[Citation12]

In addition to permanent work disability and sick leave, at-work productivity is often impacted by RA.[Citation13] It was shown that at-work productivity loss has the greatest impact on costs for RA patients, followed by wage loss from stopping or changing jobs, decreased hours and missed work days (sick leave).[Citation14] In other words, restrictions on participation in employment due to RA do not only arise incidentally by means of permanent work disability or sick leave but also structurally due to at-work productivity loss.

Varekamp et al. performed a qualitative study among RA patients with the aim to analyze factors that enable employees with RA to retain their jobs. They found that supervisor support and acceptance were the most important factors.[Citation15]

Usual care for RA patients does not include consultations with occupational health services, which may result in a lack of attention to work-related problems. In the Netherlands, patients sick-listed due to any disease visit occupational health services in case of prolonged sick leave, rather than earlier in the process to prevent limitations in work activities.[Citation16] To support RA patients with work limitations, a multidisciplinary integrated care programme in which the rheumatologist and occupational health care cooperate is necessary. Because of the need for multidisciplinary recommendations for maintenance of work activities for RA patients, the Care for Work project was initiated, consisting of a two-component intervention programme to maintain and improve at-work productivity among working RA patients. The intervention programme has been proven effective before in the study of Lambeek et al.[Citation17] They showed that the intervention decreased the time until sustainable return to work for workers sick-listed due to low back pain. Another study showed that the intervention was effective on sustainable return to work for workers sick-listed due to distress if they intended to return to work despite symptoms.[Citation18] The first component of the intervention is integrated care, the second component a participatory workplace intervention.[Citation19] In addition to integrated care, we included a workplace intervention in the intervention programme, based on participatory ergonomics.[Citation20] The participatory approach was used as this approach involves both the worker and the supervisor. To implement work adjustments at the workplace, approval of the supervisor is necessary. In the workplace intervention, the worker and his/her supervisor discuss barriers at the workplace for functioning at work, and brainstorm about solutions to reduce these barriers. The intervention programme was evaluated in a randomized controlled trial (RCT). We hypothesize that, in order to improve work productivity, supervisor support needs to be addressed first. The aim of the present study was, therefore, to evaluate the effectiveness of the Care for Work intervention programme on: (1) supervisor support, (2) work instability and (3) at-work productivity loss, after 6 months of follow-up in workers with RA compared to usual care.

Methods

Details of the study design have been published elsewhere.[Citation19] The trial was registered in the Dutch Trial Register (NTR2886). All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000. Informed consent was obtained from all patients for being included in the study. This study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of the Slotervaart Hospital and Reade, and the Medical Ethics Committee of the VU University Medical Center.

Study population

The study population consists of RA patients (18–64 years) who visited a rheumatologist of either Reade (formerly, the Jan van Breemen Institute), Amsterdam, the outposts of Reade, or the Department of Rheumatology of the VU University Medical Center, Amsterdam, The Netherlands. The study population is treated according to the current insights. Eligible patients were diagnosed with RA, had a paid job (paid employment or self-employed) for at least 8 h per week, and experienced, at least, minor difficulties in functioning at work. Patients were excluded in case of severe comorbidity that would hamper compliance to the protocol (not being able to participate in all pre-defined intervention activities), inability to read or understand the Dutch language, and in the case of a current sick leave episode for more than 3 months at the time of inclusion in the study. Eligible patients received an information letter about the project from their own rheumatologist. All participants filled out a questionnaire at baseline and after 6 months.

Randomization, blinding and sample size

Randomization to either the intervention or control group was performed on patient level. Patients were pre-stratified by three prognostic factors: gender, the number of working hours per week and whether a patient performed heavy or light physically/mentally demanding work, based on the classification of de Zwart (1997).[Citation21] To randomize, we used the minimization method, by applying Minim (London, UK), a software programme.[Citation22] Minimization allows pre-stratification by several prognostic factors, even in small samples.[Citation23,Citation24] Due to the character of the intervention, patients, therapists and researchers could not be blinded to the allocated treatment after randomization. The sample size was calculated according to the number of patients needed to show an effect on at-work productivity loss, expressed as hours lost from work due to presenteeism, measured with the Work Limitations Questionnaire (WLQ).[Citation25] We assumed that a difference of 2 h per 2 weeks was a minimal relevant difference, based on a study where an average of four lost hours per 2 weeks (SD: 3.9) was found with the WLQ.[Citation13] A 2 h per 2 weeks difference implies a moderate standardized effect of 0.5. Power analysis revealed a sample size of 71 patients per group. Assuming a dropout rate of 15%, 142 patients had to be included in the total, with a power of 0.80 and an alpha of 0.05.

Intervention and control group

All patients received usual rheumatologist-led care, which means that they are treated according to the current guidelines and insight as performed in The Netherlands. The patients in the intervention programme also received the Care for Work intervention programme.[Citation19] depicts the intervention programme schematically. The programme consisted of two components which complemented each other; integrated care and a participatory workplace intervention. Integrated care was delivered by a multidisciplinary team, which consisted of a trained clinical occupational physician (who acted as care manager), a trained occupational therapist and the patients’ own rheumatologist. The aim of integrated care was for all members of the multidisciplinary team to have the same treatment goal towards the patient. The care manager was responsible for the planning and coordination of care and for communication between members of the multidisciplinary team, the patient’s supervisor, occupational physician and general practitioner. The care manager started the intervention with the intake of the patient. The care manager started with history taking and physical examination with the goal to identify functional limitations at work and factors that could influence functioning at work. The care manager proposed a treatment plan at the end of the first consultation. After the patient’s consent, the care manager sent the treatment plan to the other members of the multidisciplinary team. The patients visited the care manager again after 6 and 12 weeks to evaluate, and, if necessary, adjust the treatment plan. After the occupational therapist received the treatment plan from the care manager, the occupational therapist started the participatory workplace intervention, which is based on active participation and strong commitment of both the patient and supervisor. The workplace intervention was based on methods used in participatory ergonomics.[Citation16,Citation20,Citation26] Participatory ergonomics has been defined as “practical ergonomics with the participation of the necessary actors in problem solving”.[Citation27] Participatory ergonomics empowers workers to design and change their own work, and consequently in decreasing risk factors at work.[Citation28,Citation29] The aim of the workplace intervention was to discuss obstacles at the workplace for work functioning and achieve consensus between patient and supervisor regarding feasible solutions for these obstacles. After consensus, the occupational therapist, patient and supervisor agreed on which solutions had to be implemented and described these in a plan of action. The patient and the supervisor were responsible for implementing the solutions described in the plan of action. The occupational therapist evaluated the implementation of the action plan with the patient and supervisor after 4 weeks.

Figure 1. Time scheduling of the multidisciplinary intervention program. COP: clinical occupational physician; OT: occupational therapist; OP: occupational physician; WI: workplace intervention [Citation19].

![Figure 1. Time scheduling of the multidisciplinary intervention program. COP: clinical occupational physician; OT: occupational therapist; OP: occupational physician; WI: workplace intervention [Citation19].](/cms/asset/a83e3c8b-833d-4ef3-bc65-3e6229544ddc/idre_a_1145257_f0001_b.jpg)

Outcome measures

Supervisor support

Supervisor support refers to the support an employee experiences from his supervisor. We measured supervisor support with the subscale supervisor social support of the Job Content Questionnaire (JCQ).[Citation30] The subscale consists of four items, which are answered on a scale of 1 to 4 (totally disagree to totally agree). The four items concern the themes: supervisor is concerned, supervisor pays attention, helpful supervisor and supervisor good organizer. Cronbach’s alpha for this subscale is 0.83.[Citation30] Scoring of the scale leads to a score ranging from 1 to 4, a higher score indicates more experienced supervisor support.

Work instability

Work instability refers to a mismatch between job demands and abilities of a worker. A person with high work instability is at risk of becoming work disabled. We measured work instability with the RA Work Instability Scale (RA-WIS).[Citation31,Citation32] The RA-WIS contains 23 statements such as “I’m getting up earlier because of the arthritis”, “I can get my job done, I’m just a lot slower” and “I feel I may have to give up work”. By counting the statements answered by yes, the RA-WIS score is calculated, leading to a score between 0 and 23. A higher score indicates more work instability, and hence, a higher risk of job loss.

Work productivity

At-work productivity was investigated as hours lost from work due to presenteeism. Presenteeism refers to being present on the job, but being limited in meeting work demands. Presenteeism was measured by means of the WLQ. The WLQ consists of 25 items based on which a score was calculated which presents the percentage of at-work productivity loss. The WLQ has a recall period of 2 weeks. This score was multiplied by the number of work hours per 2 weeks, resulting in an estimation of the hours that a participant was not fully productive and experienced at-work productivity loss during the past 2 weeks. The WLQ furthermore consists of four subscales (time management demands, physical demands, mental-interpersonal demands and output demands) which are calculated into scores ranging from 0 (no limitations) to 100 (highest limitations). The internal reliability is high for the separate WLQ subscales, time management (Cronbach’s alpha (α) = 0.87), physical demands (α = 0.83), mental-interpersonal demands (α = 0.83) and output demands (α = 0.84).[Citation33] Cronbach’s alpha for the total WLQ score is 0.88.[Citation33] The good validity and reliability of the WLQ concerning RA have been shown in several previous studies.[Citation33–35]

Potential confounders

As we used minimization for group allocation, we assessed potential confounders in order to be able to adjust our effect analyses in case of relevant differences between the intervention and the control group. Gender and age were collected from patient medical records. Education level was measured using one single item in the questionnaire. Low education was operationalized as primary school, middle education or basic vocational education. Middle education was operationalized as secondary vocational education or intermediate vocational education. High education was operationalized as higher vocational education or a university degree. The Disease Activity Score of 28 joints (DAS28) was assessed as a part of usual care and was collected from patient records. The DAS28 score was based on the number of tenders and swollen joints in 28 joints, the erythrocyte sedimentation rate and the patient’s general health measured on a visual analogue scale of 100 mm.[Citation36] We furthermore retrieved the use of biological therapeutics from the patient medical records. The presence of comorbidity (yes/no) was investigated by a list with 15 common comorbidities, including cardiovascular diseases, diabetes mellitus and psychological complaints such as depression. Disease duration was investigated by one open-ended question about the year of the RA diagnosis, as well as the duration of complaints due to RA (answer categories were 0–2 years, 3–5 years, 6–10 years, >10 years). Daily functioning was measured with the Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ), a reliable and valid questionnaire widely used in RA research.[Citation37] We also measured several variables related to the work situation of the participant. We measured co-worker support, decision authority, psychological and physical job demands with subscales of the JCQ.[Citation30] We asked participants to their type of job contract (permanent contract; self-employed). We furthermore asked patients whether they were satisfied with their job (not/moderately satisfied; (very) satisfied). We measured the quality of life with the RAND 36.[Citation38,Citation39] All nine subscales of the RAND 36 were included in the questionnaire (mental health (1), pain (2), physical role limitations (3), physical functioning (4), social functioning (5), vitality (6), emotional role limitations (7), general health perception (8) and perceived health change (9). We furthermore included baseline data of all of the outcomes described above as potential confounders.

Co-interventions

We collected data on co-interventions used by our participants to be able to determine whether the use of co-interventions might have intervened with our intervention effects. Information about all treatments and co-interventions received by patients were collected by means of two questions in the questionnaire. These questions were asked to patients in the intervention as well as in the control group. We asked participants whether their work situation was adapted during the past 6 months related to their work functioning. We indicated that these adaptations should not be related to the Care for Work intervention programme. We furthermore asked participants to describe the adaptations that were implemented at their work.

Statistical analyses

Participants in the control and intervention group were checked for baseline differences in outcome variables or potential confounders. To determine the effects of the intervention programme at 6 months of follow-up, linear regression analyses were performed with the outcome variable of interest as the dependent variable, and group allocation as the independent variable. All analyses were performed according to the intention to treat principle. All analyses were corrected for the baseline values of the outcome variable. Analyses were checked for potential confounders with a forward procedure. A potential confounder was included in the analyses when a >10% change occurred in the regression coefficient. We checked effect modification for the use of co-interventions. p Values <0.05 were considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed using SPSS software (version 20.0, Chicago, IL).

An additional post-hoc analysis was performed on subgroups based on compliance with the intervention. We performed this analysis to gain insight into the relationship between compliance with the intervention programme and the effects of at-work productivity loss. We defined three core components of our intervention, the intake by the care manager, the workplace visit by the occupational therapist and the evaluation by the occupational therapist. Compliance categories were then operationalized as: 1) no intervention (usual care group), 2) low compliance: participants who did not receive all three core components, 3) high compliance: participants who received all three core components. Linear regression coefficients were calculated for high and low compliance, using the usual care group as the reference category.

Results

Participants

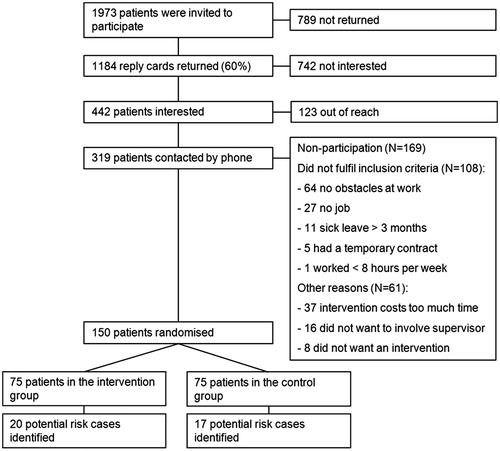

We invited 1973 RA patients to participate in the study, of which 442 patients expressed an interest to participate. Of these, 292 patients did not participate, either because they could not be contacted (n = 123), did not meet the inclusion criteria (n = 108) or had other reasons (n = 61) (). We randomized 150 patients into either the control (n = 75) or the intervention group (n = 75). During the 6 months follow-up period, three participants were lost-to-follow-up; one in the intervention group, and two in the control group.

Baseline characteristics of the study sample are described in . Participants were 50 years of age on average, and mostly women participated in the study. The mean score on the HAQ was low, which means that participants had a relatively good daily functioning. The mean DAS28 score was 2.7. When the DAS28 score is lower than 2.6, there is remission. Our mean score indicates that many participants were in remission. The use of biological therapeutics was relatively high (45–48%), and on average, disease duration was 10 years. We found significant baseline differences on the WLQ score and RA-WIS score; the intervention group reported significantly more lost hours due to presenteeism, and more work instability.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of the study population by allocated treatment.

Due to a systematic error in our minimization procedure, a subgroup of 37 participants was considered at risk to be mistakenly allocated to the control or intervention group. For this reason, we conducted a sensitivity analysis on a subgroup in which we left out the 37 participants at risk, to determine the impact of the potential bias on the study results. In the subgroup for the sensitivity analysis, 55 patients were randomized into the intervention group and 58 patients in the control group. Before conducting the sensitivity analyses, a change in the regression coefficients of >10% between the two analyses was defined as a relevant difference. All analyses were replicated by an independent researcher.

Examples of obstacles and solutions as proposed by the patient and his supervisor during the participatory workplace intervention are described in .

Table 2. Examples of obstacles and solutions as proposed during the participatory workplace intervention.

Intervention effects

Supervisor support

shows the mean values of the outcome variables for the intervention and control group, both at baseline and after 6 months. Furthermore, shows the estimated intervention effects. A statistically significant effect was found on supervisor support, with a difference between the groups of 0.19 (95% CI: 0.007–0.38), in favour of the intervention group. Co-interventions were not a significant effect modifier in the present study.

Table 3. Intervention effects on work productivity, work instability and supervisor support (N = 150).

Work instability

We found no statistically significant effect on work instability, our adjusted analysis (in which we added confounders to the model) shows a difference between the groups of −0.50 (95% CI: −1.71–0.71).

Work productivity

presents the mean value at baseline and 6 months follow-up for the outcome at-work productivity loss, as well as the subscales of the WLQ. We found no statistically significant effect on overall at-work productivity loss. Our adjusted analyses showed a difference between the groups of 0.1 (95% CI: −0.7–0.9). We also did not find significant effects on the subscales of the WLQ. All subscales show a slight non-significant increase of limitations in the intervention group, except for the subscale physical demands, where a slight non-significant decrease was shown in the intervention group.

Sensitivity analysis

In the subgroup, we found no statistically significant effect on at-work productivity loss (B: 0.3 (95% CI: −0.7–1.2)).

Post-hoc analysis

shows the results of the subgroup analysis based on compliance with the intervention. Compliance was not related to the intervention effects on at-work productivity loss and work instability. Both the subgroup with low compliance as well as the subgroup with high compliance showed no intervention effects on these two outcomes. On the outcome supervisor support, there is a relation between compliance and intervention effects. The subgroup with low compliance shows no effect on supervisor support, while the subgroup with high compliance shows a statistically significant intervention effect on supervisor support, compared to the control group.

Table 4. Effect of the intervention on at-work productivity loss in subgroups based on low and high compliance to the intervention compared to the control group.

Discussion

Main findings

We evaluated an intervention programme consisting of integrated care and a participatory workplace intervention. We found a beneficial intervention effect on supervisor support. We furthermore found that compliance to the intervention was related to intervention effects. Participants with high compliance perceived more supervisor support than participants in the control group while participants with low compliance had no effects when compared to the control group on supervisor support. We found no intervention effects after 6 months of follow-up on work instability and at-work productivity loss. We furthermore showed no relationship between compliance to the intervention and effects on at-work productivity loss.

Comparison with other studies

Our intervention shows a beneficial effect on the outcome supervisor support. Although significant, the effect size is rather small (B: 0.19), so this finding should be interpreted with caution. The supervisor support scale we used ranges from 1 to 4. At baseline, our participants in both the intervention and control group scored 3.0. After follow-up, participants in the intervention group scored supervisor support at 3.0, while participants in the control group gave a score of 2.9. Although in current literature there is no consensus about a relevant effect size on the supervisor support scale, we consider a change over time of 0.1 as not relevant. Supervisor support was already rated high by our participants at baseline (3 points out of a possible 4), therefore, there was not much room for improvement. The content of our intervention might have led to selection bias. Participants with a troublesome relationship with their supervisor might have been hesitant to participate because close collaboration with the supervisor was an essential element of the intervention programme.

Previous studies evaluated work-related interventions for workers with RA as well, with mixed results, although these studies did not focus on supervisor support as an outcome. An example of an intervention that showed positive effects was described by Macedo et al.[Citation40] This comprehensive occupational intervention consisted of an assessment of the patient’s medical history, and a work-, functional- and psychosocial assessment, including a work visit. In contrast to our participants, participants to the Macedo study had medium or high work disability risk on the RA-WIS at baseline. The Macedo intervention was significantly beneficial on the work outcomes RA-WIS, work satisfaction and work performance. Since we did not select patients based on the severity of limitations, we might have included a sample only moderately limited in their work functioning. Patients with more severe limitations in work functioning might have more to gain from a workplace intervention. Our aim with our workplace intervention was to make adaptations in order to decrease barriers for work performance at the workplace. If our participants were only slightly limited, there might not have been much room for improvement.

In the study of Baldwin et al., a workplace ergonomic intervention was evaluated, which consisted of individual workplace assessments, resulting in a work plan to improve arthritis-related vocational difficulties.[Citation41] Eligibility criteria were comparable to our study. The Baldwin intervention was effective after 24 months, the intervention group reported less arthritis-related impact on their work. No effects were found on job satisfaction, physical functioning, pain and psychosocial well-being. No effects were found after 12 months of follow-up in this study. The need for work-related interventions for workers with RA has been highlighted before. Studies of interventions that have been evaluated so far show variable results. From previous studies, it seems that an intervention including a workplace visit might be recommended.[Citation42]

We measured our outcomes after 6 months of follow-up; this might have been too rapidly after the intervention programme, although the results are in accordance with our conceptual model. We expect a change in supervisor support first before work performance related outcomes can improve. Although we also included a workplace visit in our intervention, our results did not show any effects of the workplace intervention on at-work productivity loss and work instability. Another point for discussion is that we included participants with a wide range of disease durations, with a mean duration of 10 years. The interventions described above also had no inclusion criteria related to disease duration. In other literature, it has been emphasized that work-related interventions might be more effective for workers with early RA. Eberhardt argued that very early intervention is essential to prevent work loss in patients with RA.[Citation43] This was also shown by Han et al.[Citation44] They suggest that intervention as early as possible in the disease course maximizes the employment potential of a patient.[Citation44] These two articles concern job loss, which is a different concept than functioning at work. Our participants are still working on their diagnosis. Job loss occurs mostly in the first couple of years after diagnosis, and patients without a paid job could not participate in our study. We might have therefore included a relatively healthy sample of patients, who are healthy enough to continue working, and hence, their work situation might be stable. An intervention very early in the disease course might have benefitted those at risk for job loss.

Strengths and limitations

A strength of the current study is that we applied an RCT study design. We furthermore evaluated an intervention that was shown to be effective in previous studies; although for different disabilities, and for the outcome return to work instead of at-work productivity. As described before, Lambeek et al. and van Oostrom et al. showed the effectiveness of the intervention on time until sustainable return to work for workers sick-listed due to back pain and distress, respectively.[Citation17,Citation18] The participatory workplace intervention was evaluated among sick-listed workers. In the current study, we chose to include workers not (yet) sick-listed but limited in their work functioning. Employees who are already work disabled hardly return to work, and, therefore, we chose to include workers who had not reached that stage yet.

We invited 1973 patients to participate in the study, and only 442 expressed an interest, which might have led to bias. The relatively low number patients expressing an interest might be caused, however, by the fact that we invited the general RA population within the age group of 18–64 of the participating hospitals without knowing if they had a paid job or not. In the information letter, it was emphasized that patients could only participate in the study if they had a paid job. It is likely that this has lowered the number of patients expressing an interest.

A strength of our study is that we measured our outcomes (supervisor support – subscale of the JCQ, work instability – RA-WIS, at-work productivity loss – WLQ) with questionnaires which are validated. Although for at-work productivity loss there is no consensus yet about which measurement instrument to use, the WLQ is the best instrument available [Citation45] and furthermore the WLQ has been validated among populations with arthritis.[Citation33,Citation34]

Our sensitivity analyses revealed that the systematic error in group allocation relevantly influenced our results as the regression coefficients between the total group and subgroup analyses differed > 10%. However, as both analyses resulted in non-significant results in the same direction, the allocation error did not influence our conclusions.

Study implications for research and practise

It is clear that workers with RA are in need of effective interventions to prevent job loss, and support them in their work functioning. Up to now, it is not clear which intervention components are required. There are indications that an intervention carried out at the workplace to enhance supervisor support and reduce barriers for work functioning might be helpful, and results of this study show that a workplace intervention might improve supervisor support. Future research should focus on which workers are in need of an intervention to enhance supervisor support, and which intervention would address their problems best. Our intervention did show promising effects on supervisor support, but its effectiveness on improving work functioning, in the long run, has to be established in future research.

Conclusion

Our intervention programme, consisting of integrated care and a participatory workplace intervention, showed a small positive effect on supervisor support but did not show any effects on work instability or at-work productivity. Future research should show whether this significant but small increase in supervisor support is effective to support workers with RA in their work functioning. Further research is furthermore needed to gain insight into ceiling effects of the measures we used, or on optimal follow-up duration as changes in work instability or at-work productivity following the intervention may need more time than 12 months. This study shows clinicians that patients with RA who are still working can still experience limitations, and might be in need of adjustments to the work environment. Our results do not support the usefulness of our intervention for the present study population.

Funding information

Financial support was provided by Instituut GAK.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of this article.

References

- Pereira da Silva JA, Woolf AD. Rheumatology in practice. London: Springer; 2010.

- Lopez-Olivo MA, Siddhanamatha HR, Shea B, et al. Methotrexate for treating rheumatoid arthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;6:CD000957.

- Singh JA, Christensen R, Wells GA, et al. Biologics for rheumatoid arthritis: an overview of Cochrane reviews. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;4:CD007848.

- Flurey CA, Morris M, Richards P, et al. It’s like a juggling act: rheumatoid arthritis patient perspectives on daily life and flare while on current treatment regimes. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2014;53:696–703.

- Boonen A, Severens JL. The burden of illness of rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Rheumatol. 2011;30:S3–S8.

- Citera G, Ficco HM, Alamino RS, et al. Work disability is related to the presence of arthritis and not to a specific diagnosis. Results from a large early arthritis cohort in Argentina. Clin Rheumatol. 2015;34:929–933.

- Kerola AM, Kauppi MJ, Nieminen T, et al. Psychiatric and cardiovascular comorbidities as causes of long-term work disability among individuals with recent-onset rheumatoid arthritis. Scand J Rheumatol. 2015;44:87–92.

- Huscher D, Mittendorf T, von Hinüber U, et al. Evolution of cost structures in rheumatoid arthritis over the past decade. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;74:738–745.

- Skakon J, Nielsen K, Borg V, et al. Are leaders’ well-being, behaviours and style associated with the affective well-being of their employees? A systematic review of three decades of research. Work Stress 2010;24:107–139.

- Baruch-Feldman C, Brondolo E, Ben-Dayan D, et al. Sources of social support and burnout, job satisfaction, and productivity. J Occup Health Psychol. 2002;7:84–93.

- Stansfeld SA, Rael EG, Head J, et al. Social support and psychiatric sickness absence: a prospective study of British civil servants. Psychol Med. 1997;27:35–48.

- Nielsen ML, Rugulies R, Christensen KB, et al. Psychosocial work environment predictors of short and long spells of registered sickness absence during a 2-year follow up. J Occup Environ Med. 2006;48:591–598.

- Zhang W, Gignac MA, Beaton D, et al. Productivity loss due to presenteeism among patients with arthritis: estimates from 4 instruments. J Rheumatol. 2010;37:1805–1814.

- Zhang W, Anis AH. The economic burden of rheumatoid arthritis: beyond health care costs. Clin Rheumatol. 2011;30:S25–S32.

- Varekamp I, Haafkens JA, Detaille SI, et al. Preventing work disability among employees with rheumatoid arthritis: what medical professionals can learn from the patients’ perspective. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;53:965–972.

- Lambeek LC, Anema JR, van Royen BJ, et al. Multidisciplinary outpatient care program for patients with chronic low back pain: design of a randomized controlled trial and cost-effectiveness study [ISRCTN28478651]. BMC Public Health. 2007;7:254.

- Lambeek LC, van MW, Knol DL, et al. Randomised controlled trial of integrated care to reduce disability from chronic low back pain in working and private life. BMJ. 2010;340:c1035.

- van Oostrom SH, van Mechelen W, Terluin B, et al. A workplace intervention for sick-listed employees with distress: results of a randomised controlled trial. Occup Environ Med. 2010;67:596–602.

- van Vilsteren M, Boot CR, Steenbeek R, et al. An intervention program with the aim to improve and maintain work productivity for workers with rheumatoid arthritis: design of a randomized controlled trial and cost-effectiveness study. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:496.

- Anema JR, Steenstra IA, Urlings IJ, et al. Participatory ergonomics as a return-to-work intervention: a future challenge? Am J Ind Med. 2003;44:273–281.

- de Zwart BC, Broersen JP, van der Beek AJ, et al. Occupational classification according to work demands: an evaluation study. Int J Occup Med Environ Health. 1997;10:283–295.

- Evans S, Royston P, Day S. Minim: allocation by minimisation in clinical trials. Avaliable from: http://www-users.york.ac.uk/~mb55/guide/minim.htm.

- Scott NW, McPherson GC, Ramsay CR, et al. The method of minimization for allocation to clinical trials. A review. Control Clin Trials. 2002;23:662–674.

- Altman DG, Bland JM. Treatment allocation by minimisation. BMJ. 2005;330:843.

- Twisk JWR. Sample size calculations. In: Twisk JWR, editor. Applied longitudinal data analysis for epidemiology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2003. p. 280–285.

- Steenstra IA, Anema JR, Bongers PM, et al. Cost effectiveness of a multi-stage return to work program for workers on sick leave due to low back pain, design of a population based controlled trial [ISRCTN60233560]. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2003;4:26.

- Kuorinka I. Tools and means of implementing participatory ergonomics. Int J Ind Ergon. 1997;19:267–270.

- Vink P, Koningsveld EA, Molenbroek JF. Positive outcomes of participatory ergonomics in terms of greater comfort and higher productivity. Appl Ergon. 2006;37:537–546.

- Bongers PM, Kremer AM, ter Laak J. Are psychosocial factors, risk factors for symptoms and signs of the shoulder, elbow, or hand/wrist? A review of the epidemiological literature. Am J Ind Med. 2002;41:315–342.

- Karasek R, Brisson C, Kawakami N, et al. The Job Content Questionnaire (JCQ): an instrument for internationally comparative assessments of psychosocial job characteristics. J Occup Health Psychol. 1998;3:322–355.

- Gilworth G, Chamberlain MA, Harvey A, et al. Development of a work instability scale for rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;49:349–354.

- Gilworth G, Emery P, Gossec L, et al. Adaptation and cross-cultural validation of the rheumatoid arthritis work instability scale (RA-WIS). Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68:1686–1690.

- Walker N, Michaud K, Wolfe F. Work limitations among working persons with rheumatoid arthritis: results, reliability, and validity of the Work Limitations Questionnaire in 836 patients. J Rheumatol. 2005;32:1006–1012.

- Lerner D, Reed JI, Massarotti E, et al. The Work Limitations Questionnaire’s validity and reliability among patients with osteoarthritis. J Clin Epidemiol. 2002;55:197–208.

- Allaire SH. Measures of adult work disability. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;49:85–89.

- Leeb BF, Andel I, Sautner J, et al. The Disease Activity Score in 28 joints in rheumatoid arthritis and psoriatic arthritis patients. Arthritis Rheum. 2007:57:256–260.

- Bruce B, Fries JF. The Stanford Health Assessment Questionnaire: a review of its history, issues, progress, and documentation. J Rheumatol. 2003;30:167–178.

- Moorer P, Suurmeije ThP, Foets M, et al. Psychometric properties of the RAND-36 among three chronic diseases (multiple sclerosis, rheumatic diseases and COPD) in The Netherlands. Qual Life Res. 2001;10:637–645.

- Van der Zee KI, Sanderman R. Het meten van de algemene gezondheidstoestand met de RAND-36: een handleiding. Groningen: Noordelijk Centrum voor Gezondheidsvraagstukken, Rijksuniversiteit Groningen; 1993.

- Macedo AM, Oakley SP, Panayi GS, et al. Functional and work outcomes improve in patients with rheumatoid arthritis who receive targeted, comprehensive occupational therapy. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;61:1522–1530.

- Baldwin D, Johnstone B, Ge B, et al. Randomized prospective study of a work place ergonomic intervention for individuals with rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2012;64:1527–1535.

- de Buck PD, le Cessie S, van den Hout WB, et al. Randomized comparison of a multidisciplinary job-retention vocational rehabilitation program with usual outpatient care in patients with chronic arthritis at risk for job loss. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;53:682–690.

- Eberhardt K. Very early intervention is crucial to improve work outcome in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2009;36:1104–1105.

- Han C, Smolen J, Kavanaugh A, et al. Comparison of employability outcomes among patients with early or long-standing rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;59:510–514.

- Noben CY, Evers SM, Nijhuis FJ, et al. Quality appraisal of generic self-reported instruments measuring health-related productivity changes: a systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:115.