Abstract

Purpose: To determine if non-occupational therapists (non-OTs) with different job titles using Algo, a clinical algorithm for recommending bathroom modifications (e.g., bath seat) for community-dwelling elders in “straightforward” situations, will make clinically equivalent recommendations for standardized clients. Method: Eight non-OTs (three social workers, two physical rehabilitation therapists, two homecare aides and one auxiliary nurse) were trained on Algo and used it with six standardized clients. Bathroom adaptations recommended (one of nine options) by non-OTs were compared to assess interrater agreement using Fleiss adapted kappa. Results: Estimated kappa was 0.43 [0.36; 0.49] qualified as a moderate agreement, according to Landis and Koch’s arbitrary divisions, among the recommendations of non-OTs. However, clinical equivalence is reached, since safety and client needs were met when raters selected two different options (e.g., with or without a seat back). Conclusions: Non-OTs using Algo in the same simulated clinical scenarios recommend clinically equivalent bathroom adaptations, increasing the confidence regarding the interrater reliability of Algo used by non-OT members of homecare interdisciplinary teams

In homecare services, non-occupational therapists from different health care disciplines (e.g., homecare aides, social workers, physical rehabilitation therapists) may be asked to select assistive devices for the hygiene care of clients living at home.

Algo was designed to guide non-occupational therapists in the selection of assistive devices when performed with clients in straightforward cases.

This study indicates that non-occupational therapists using Algo recommend similar and acceptable bathroom adaptations to enhance client safety.

Implications for Rehabilitation

Introduction

Bathing is a common reason for intervention in homecare occupational therapy in Quebec, Canada.[Citation1,Citation2] This is not surprising in an aging population where staying at home as long as possible is often the first choice,[Citation3] and also since bathing is the most problematic activity of daily living associated with aging.[Citation4–6]

Despite this reality, it is noticed that in homecare occupational therapy in Health and Social Services Centers (HSSCs) providing publicly funded services to the Quebec population, the priority criterion to determine the degree of urgency for bathing difficulties is quite moderate, thus leading to a target wait time of 3–6 months.[Citation1] Some consider this wait time as unacceptable [Citation7] because the risk of bathroom falls is elevated, and both prevention of injury and promotion of functional autonomy are essential for the elderly.[Citation8,Citation9]

Therefore, to support extended roles and cross-skilling within interdisciplinary teams (i.e., skill mix) [Citation10,Citation11] as an alternative to long wait times in occupational therapy, the clinical algorithm Algo was recently developed [Citation12] for the selection of bathing equipment by non-occupational therapists (non-OTs) for community-dwelling elders in straightforward cases. Such cases are adults with morphology that is within the norm, presenting foreseeable difficulties with occupational performance during personal hygiene in a standard environment.[Citation13] Usually, in Quebec homecare services, referrals for bathing difficulties are first analyzed to identify these straightforward cases that could be referred to non-OTs (e.g., homecare aides).[Citation14]

Considering this context of practice, Algo’s criterion validity was recently studied.[Citation15] To determine if Algo guides towards the appropriate bath seat, eight homecare aides trained in using Algo met with community-dwelling elders, and their bath seat recommendations were compared to those proposed by research team OTs (criterion) who had visited the same individuals. To enrich the interpretation of the agreement between recommendations, a subgroup of community-dwelling elders was assessed a third time by clinical OTs from participating HSSCs. In 84% of the cases (95% CI = [75, 93]), non-OTs using Algo identified a seat that would enable these elderly people to bathe according to their preferences, abilities and settings. Moreover, the appropriateness rate of seats recommended by homecare aides did not statistically differ from that of the two clinical OTs (84 vs. 89.5%, p = 0.48).

As documented in a census conducted in 2009, 87 out of 98 (89%) of all HSSCs in Quebec solicited the services of non-OTs to recommend technical assistance for bathing. Homecare aides are the most common members of the interdisciplinary team who take on this role, in addition to the OTs. Other members with different job titles are potential users of Algo in half of the HSSCs listed, such as physical therapists, physical rehabilitation therapists, social workers and nursing staff.[Citation14] However, recommendations made by non-OTs with job titles other than homecare aides using Algo were not studied. Moreover, no previous study has focused on Algo’s interrater reliability. This study aimed to estimate Algo’s interrater reliability by exploring if non-OTs with different job titles made clinically equivalent recommendations when assessing standardized clients.

Methods

Design

This is a psychometric study on Algo that focuses on its interrater reliability. To estimate interrater reliability, non-OTs with different job titles administered Algo to six standardized clients,[Citation16,Citation17] and their recommendations were compared.

Algo

Algo [Citation12,Citation18] is a clinical algorithm for selecting bathing equipment for community-dwelling elders in straightforward situations. Administered at home, Algo has four sections: (1) Clientele, (2) Selecting a Seat, (3) Recommendations, and (4) Notes.

The first two sections (Clientele and Selecting a Seat) are illustrated with blue waves that separate the items according to three components: occupation, person, and environment. Simple questions guide the non-OTs’ observations: they must respond by either yes or no to the items, checking them off to indicate the path taken through Algo, which is designed as a decision tree. When Algo leads non-OTs to a STOP box, they should refrain from making any recommendations. STOP boxes indicate that the case could be more complex than anticipated. As recommended by the Ordre des ergothérapeutes du Québec [Citation7,Citation19,Citation20] and the Canadian Association of Occupational Therapists,[Citation7] in those situations (about 17% according to a previous study [Citation15]), non-OTs should seek guidance with an OT in his/her role, or refer the client for an OT evaluation.

Section 3, Recommendations, can be removed from the questionnaire and given to the client. All clients receive general recommendations made by non-OTs using Algo, such as add two wall grab bars, put non-slip mats inside and outside the bathtub or shower stall and clear some space in the bathroom. In addition, clients are given one of nine recommendations regarding how to perform full body bathing, taking into account their preferences, capacities and environment: (A) standing, without a seat, in the bathtub, (B) standing, without a seat, in the shower stall, (C) sitting on a bath stool in the bathtub, (D) sitting on a bath stool in the shower stall, (E) sitting on a bath chair in the bathtub, (F) sitting on a bath chair in the shower stall, (G) sitting on a board in the bathtub and (H) sitting on a bath transfer bench in the bathtub. For each client, non-OTs need to select a combination of position (standing or sitting), bath seat (none, bath stool, bath chair, board or bath transfer bench) and location (bathtub or shower stall) for bathing. Non-OTs can also refrain from making recommendations if the situation seems complex (i.e., stop box or non-OTs doubt) and (I) refer the client to an OT. The fourth and last section provides space for non-OTs to jot down questions.

Participants

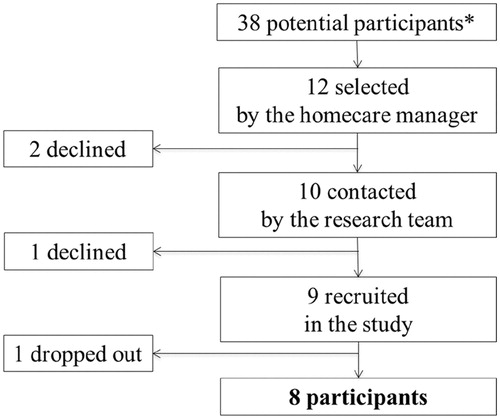

Participants were non-OTs with different job titles working as part of the same homecare interdisciplinary team at a HSSC. For human resource management purposes, homecare managers themselves selected non-OTs for training on using Algo (convenience sample; ). The research team acceded to this request because it was consistent with the context in which Algo is used in HSSCs.

Figure 1. Flow diagram of participants’ recruitment. *Job titles of potential participants in HSSC interdisciplinary teams: 15 homecare aides, 8 social workers, 4 physical rehabilitation therapists, 6 clinical nurses, 2 nurse technicians, 2 auxiliary nurses and 1 physiotherapist.

All non-OTs received the same training, provided by two OTs from the research team, over a two-day period (7 h), to learn how to administer Algo. More specifically, the training program was similar to the one used in previous studies, and included lectures (development, content and use of Algo), role modelling, peer feedback, and individual work. Algo comes with a users’ guide that was handed out to trainees.[Citation15,Citation18] At the end of the training session, the data collection process was explained, and informed consent was obtained for each participant.

Simulated clinical scenarios

Simulated clinical scenarios were developed by an OT (referred to below as OT-scriptwriter) who had (a) practiced as a homecare OT, (b) taught and evaluated undergraduate OTs using standardized clients, and (c) trained non-OTs to use Algo. OT was asked to extract straightforward clinical scenarios within research files from a previous study of Algo conducted with 65 community-dwelling older adults evaluated to make their bathroom safer. The OT was thereafter asked to identify: (1) the best equipment recommendation for each clinical scenario and (2) the recommendations considered as clinically equivalent meaning that the equipment chosen meets the client’s needs and ensures his/her safety.

Such clinical scenarios involved adults with normal-range morphology, presenting foreseeable difficulties with occupational performance during personal hygiene in a standard environment.[Citation13] Criteria for a straightforward clinical scenario were: (1) being able to get to the tub or shower stall with or without assistive mobility devices, but without human assistance; (2) not needing or wishing to soak in the water (no transfer to the bottom of the tub); (3) being aged 18 years old or over; (4) weighing less than 250 pounds; (5) having a stable medical condition (neither degenerative neurological disease nor end-of-life condition); (6) having no medical restrictions (no restriction such as partial weight bearing); (7) being able to stand up with or without support for 5 seconds; (8) can use a bar for support; (9) being able to follow simple instructions (neither severe dementia nor misbehavior); and (10) using a standard shower stall or bathtub at home (neither podium tub nor tub on legs).[Citation13] A convenient number of six simulated clinical scenarios was selected since it covered a variety of Algo’s potential recommendations for bathing in home environments, including at least one instance of bathing: (1) standing in a shower stall, (2) sitting on a bath stool, (3) sitting on a bath chair, and (4) sitting on a bath board or bath transfer bench.

The simulated clinical scenarios were written by the OT-scriptwriter as scenarios to be played out by standardized clients in their own homes (Appendix 1). The term “client” here was chosen because of the nomenclature used in the Canadian [Citation21] and Quebec [Citation19] contexts. Standardized clients are individuals paid to learn and simulate a pre-established clinical scenario in the field of health education.[Citation16,Citation17] In this study, each of the standardized clients simulated a specific clinical scenario and were asked to repeat and maintain the same performance with each participant (eight non-OTs with different job titles using Algo), without considering the previous participant’s performance. The chosen standardized clients had consistent social history, physical characteristics and home environment with his/her simulated clinical scenario.

Each simulated clinical scenario was pre-tested by one of two non-OT research assistants trained to use Algo. Pretests were filmed with a head-mounted video camera.[Citation22] The OT-scriptwriter watched each video to provide feedback to maximize standardization of clients about their performance, prior to data collection.

Data collection

Non-OTs with different job titles administered Algo to the six standardized clients in their own homes during the week following the training session. The main variable was the custom recommendation made by non-OTs with different job titles to the standardized client (A–I; see above). As planned during the development of Algo, non-OTs could call an OT from their interdisciplinary team (referred to below as the OT-partner) at any time during the administration, prior to making their decision. The OT-partner was asked to support [Citation23] non-OTs based on the information available in the Algo Reference Manual,[Citation18] professional guidelines,[Citation19,Citation20] and his/her clinical knowledge and experience.

Data collection was completed over two consecutive days, and the order of home visits was randomly selected. Each non-OT with different job titles had to visit the six standardized clients the same day, appointments being set every hour. A research assistant was present at each standardized client’s home to ensure consistency in the data collection process. Non-OTs noted their recommendations on a data collection sheet, which they handed to the research assistant with the completed Algo before leaving the standardized client’s home. To preserve non-disclosure, there was no discussion between research assistants and between non-OTs regarding the administration of Algo to standardized clients. Non-OTs submitted their recommendations without being aware of those made by others. There was a verbal agreement with standardized clients not to inform evaluators about previous visits. The OT-partner was blind to simulated clinical scenarios and expected recommendations according to the OT-scriptwriter. The OT-partner was asked to support non-OTs without considering previous exchanges with other participants.

To estimate Algo administration time, each participant administered Algo with a head-mounted video camera.[Citation22] All videos were watched by two research assistants following data collection to (a) extract the non-OT’s administration time of Algo, (b) extract discussion time with OT-partner, and (c) attest for non-OTs and standardized clients being consistent in their observations.

Data analyses

Continuous variables are presented using means and range, and categorical variables using frequencies and percentages. To estimate Algo’s interrater reliability,[Citation24] the degree of agreement was calculated using kappa.[Citation25] The formula adapted by Fleiss was computed since it allows measurement of nominal scale agreement above chance for many raters.[Citation26] Sample variation was taken into account by constructing the 95% confidence interval around kappa. Criteria proposed by Landis and Koch [Citation27] were considered when interpreting the measurements of agreement greater than chance. Indeed, Landis and Koch proposed consistent nomenclature when describing the relative strength of agreement: <0.00 = poor, 0.00–0.20 = slight, 0.21–0.40 = fair, 0.41–0.60 = moderate, 0.61–0.80 = substantial, and 0.80–1.00 = almost perfect.[Citation27]

Recommendations were judged clinically equivalent when they met the client’s needs and ensured his/her safety. For example, recommending a bath stool or a bath chair (which has a seat back) is clinically equivalent when the client needs only to sit, the seat back being non-essential without compromising the client’s safety. However, for a client who needs to sit and have support for his/her back, the bath stool and the bath chair are not clinically equivalent because the seat back is an essential feature to ensure the client’s safety and meet his/her needs.

Ethics

The research protocol was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Eastern Townships HSSCs (approval number: 2014–429). The HSSC involved in the study received a token payment to compensate for some of the time that practitioners spent on the study. A member of the research team presented the research results at the participating HSSC.

Results

Recruitment, training and data collection took place over a four-week period between February and March 2014. Eight non-OTs with different job titles administered Algo to six standardized clients (). Participants had various backgrounds (). A total of 48 home visits were completed (8 non-OTs × 6 standardized clients).

Table 1. Characteristics of participating non-occupational therapists (n = 8).

Recommendations (A–I; see above) made by non-OTs using Algo with six standardized clients are presented in . Except for clinical scenario #3 where three different recommendations were observed, other clinical scenarios led non-OTs to select two recommendations out of the possible nine. All of these recommendations were considered as clinically equivalent (). Estimated kappa is 0.43, and 95% confidence interval around agreement above chance for many raters ranges from 0.36 to 0.49.

Table 2. Recommendations made by eight non-occupational therapists using Algo in six simulated clinical scenarios.

Table 3. Recommendations made by eight non-occupational therapists using Algo in six simulated clinical scenarios compared to occupational therapist’s judgement.

Algo administration took 14 minutes on average (range: 9–22 minutes). Out of the 48 administrations by non-OTs, the OT-partner was called nine times (19%) before a recommendation was made. Average discussion time was 1 minute (range: 0.5–3 minutes). On four occasions (8%), non-OTs refrained from making a recommendation, judging the situation complex, and referred the client to an OT.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to estimate the interrater reliability of Algo, a clinical algorithm for selecting bathing equipment for community-dwelling elders in straightforward situations, administered by non-OTs with different job titles working in a homecare interdisciplinary team. Results indicate that non-OTs using Algo with standardized clients give clinically equivalent recommendations by considering the client’s needs and ensuring his/her safety during hygiene care.

Algo’s interrater reliability provides information regarding the assurance that recommendations could be replicated, if the same client was evaluated under the same circumstances by different evaluators.[Citation24] Fleiss’ adapted kappa allowed us to measure such consistency between multiple raters, calculating agreement greater than chance.[Citation26] Estimated kappa of 0.43 (95% confidence interval: 0.36–0.49) could therefore be considered fair to moderate under Landis and Koch arbitrary divisions. However, these criteria appear to be somewhat severe when patterns of non-OTs’ recommendations are examined since they are not that distinct regarding the client’s safety and needs. For instance, recommendations of non-OTs using Algo in simulated clinical scenarios varied only between two options out of a possible nine, except for standardized client #3 for whom three different recommendations were selected.

Among the factors proposed to improve reliability, many authors, as stated by Streiner et al.,[Citation28] recommend observer training, which is already available for Algo users. Considering the fact that specific strategies to use in training raters for improving reliability are not well developed,[Citation28] a qualitative study was therefore conducted as a complementary way of understanding the underlying factors of this statistical value. This study aimed to explore in-depth the clinical reasoning processes of non-OTs during administration of Algo for the interrater reliability study.[Citation29] Explicitation interviews were conducted to pinpoint items leading to disagreements to enhance the standardization of Algo’s administration. Recommendations by Ruest et al. [Citation30] have been included in the user guide for non-OTs and now provide clearer guidelines for every step when administering Algo.

Clinicians and managers could use this study for its relevance in extending the roles and cross-skilling in an interdisciplinary team. According to literature, role flexibility in the interdisciplinary team is a potential avenue to meet the challenges of this increasing population’s needs.[Citation31] An initiative such as Algo, allowing non-OTs to work in collaboration with OTs in straightforward situations, is an interesting option to allow recommendations of clinically equivalent adaptations to elders experiencing bathing difficulties in their homes. Algo could be used, for example, in situations where homecare rehabilitation human resources are scarce, a problem encountered in many countries.[Citation32–34] Indeed, results show that Algo’s administration by non-OTs with different job titles is relatively fast, requires minimal support after training, and helps non-OTs discriminate straightforward situations for which they could recommend equipment to facilitate bathing. However, future research should examine the influence of skill mix in the interdisciplinary team on client outcomes [Citation35] and in contexts different than the existing homecare services in Quebec, Canada.

Study limitations

Testing the interrater reliability of a clinical tool requires clients to have stable performances. Observed divergence of recommendations between non-OTs could be linked to standardized clients changing their answers or behaviors from one administration to the next. Enrolment of standardized clients, trained to repeat a clinical scenario based on real situations, is an original solution designed to minimize the risk of performance variations, although this risk cannot be totally eliminated.

Other members of the homecare interdisciplinary team, such as qualified nurses or respiratory therapists,[Citation14] might find it helpful to use a decision tool to select bathing equipment but they were not represented in the non-OT sample. Moreover, the judgment of non-OTs in our study may not be representative of practices outside the single interdisciplinary team concerned, all working in the same clinical context. Consequently, caution is called for when interpreting the results, since there is a potential risk of assessor bias. Nevertheless, preserving internal validity was considered more important than external validity in this psychometric study.

Parallel to the judgment of non-OTs, the limited number of clinical situations (n = 6) involves a lower number of paired comparisons between raters to calculate the kappa value. Indeed, studies about clinical tools in other fields of geriatrics such as pressure ulcer risk and pain assessment [Citation36,Citation37] tend to use a higher number of participants than the present study. However, the number of raters is lower in these two studies compared to the eight non-OTs included in this study.

Finally, it is possible that non-disclosure between participants was breached despite the short two-day timeframe for data collection and the precautions taken. The OT-partner might have unintentionally communicated information during consultations with non-OTs, or non-OTs may have unintentionally spoken to each other about the cases. Although appropriate research methods were used to prevent the unblinding of raters, this still could have occurred and is a potential limitation of this study.

Conclusions

Algo is a decision tree helping non-OTs with different job titles to select clinically equivalent bathing equipment for community-dwelling elders in straightforward situations. The study of clinically equivalent recommendations of non-OTs allows increased confidence in the interrater reliability of Algo and then favors its use by different members of homecare interdisciplinary teams. Non-OTs such as social workers, auxiliary nurses and homecare aides working with numerous older adults living at home and experiencing bathing difficulties could rely on Algo to provide sound recommendations.

Funding information

This study was financed by the Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Université de Sherbrooke, and Research Center on Aging, CSSS-IUGS.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank occupational therapy students Virginie Beaudin, Andréanne Lecours, Sophie-Andrée Marois and Marilou Trempe for their collaboration in study design and data collection; Natalie Chevalier (OT) and Audrée Jeanne Beaudoin (OT) for their contribution to data collection and analyses; and statisticians Lise Trottier and Modou Sene for their contribution to data analyses.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

References

- Raymond M-H, Feldman D, Prud’homme M-P, et al. Who’s next? Referral prioritization criteria for occupational therapy in home care. Int J Ther Rehabil. 2013;20:580–589.

- Sainty M, Lambkin C, Maile L. I feel so much safer’: unravelling community equipment outcomes. Br J Occup Ther. 2009;72:499–506.

- Ministère de la Santé et Services sociaux. Le Plan stratégique 2010–2015. Québec: Direction des communications du ministère de la Santé et des Services sociaux du Québec; 2010.

- Guay M, Dubois M-F, Corrada MM, et al. Exponential increases in the prevalence of disability in the oldest old: a Canadian national survey. Gerontology. 2014;60:395–401.

- Gitlin LN, Mann W, Tomit M, et al. Factors associated with home environmental problems among community-living older people. Disabil Rehabil. 2001;23:777–787.

- Gooch H. Assessment of bathing in occupational therapy. Br J Occup Ther. 2003;66:402–408.

- Guay M. Enjeux entourant le recours au personnel auxiliaire en ergothérapie [Issues surrounding the participation of auxiliary personnel in occupational therapy]. Can J Occup Ther. 2012;79:116–127.

- Gill TM, Guo Z, Allore HG. The epidemiology of bathing disability in older persons. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54:1524–1530.

- Dahlin-Ivanoff S, Sonn U. Use of assistive devices in daily activities among 85-year-olds living at home focusing especially on the visually impaired. Disabil Rehabil. 2004;26:1423–1430.

- Buchan J, Dal Poz MR. Skill mix in the health care workforce: reviewing the evidence. Bull World Health Organ. 2002;80:575–580.

- Stanmore E, Waterman H. Crossing professional and organizational boundaries: the implementation of generic rehabilitation assistants within three organizations in the northwest of England. Disabil Rehabil. 2007;29:751–759.

- Guay M, Dubois M-F, Robitaille J, et al. Development of Algo, a clinical algorithm for non-occupational therapists selecting bathing equipment. Can J Occup Ther. 2014;81:237–246.

- Guay M, Dubois M-F, Desrosiers J, et al. Identifying characteristics of ‘straightforward cases’ for which support personnel could recommend home bathing equipment. Br J Occup Ther. 2012;75:563–569.

- Guay M, Dubois M-F, Desrosiers J, et al. The use of skill mix in homecare occupational therapy with patients with bathing difficulties. Int J Ther Rehabil. 2010;17:300–308.

- Guay M, Dubois M-F, Desrosiers J. Can home health aids using the clinical algorithm Algo choose the right bath seat for clients having a straightforward problem? Clin Rehabil. 2014;28:172–182.

- May W, Park JH, Lee JP. A ten-year review of the literature on the use of standardized patients in teaching and learning: 1996–2005. Med Teach. 2009;31:487–492.

- Cleland JA, Abe K, Rethans JJ. The use of simulated patients in medical education: AMEE Guide No 42. Med Teach. 2009;31:477–486.

- Algo: a clinical algorithm for selecting bathing equipment. 2013. Available from: http://ergotherapie-outil-algo.ca/en/home.

- Ordre des ergothérapeutes du Québec. Participation du personnel non-ergothérapeute à la prestation des services d’ergothérapie: lignes directrices. Montréal: Ordre des ergothérapeutes du Québec; 2005.

- Ordre des ergothérapeutes du Québec. Participation du personnel non-ergothérapeute à la prestation des services d’ergothérapie. Lignes directrices (OEQ, 2005) – addenda (OEQ, 2008). Montréal: Ordre des ergothérapeutes du Québec; 2008.

- Canadian Association of Occupational Therapists (CAOT). Profile of occupational therapy practice in Canada. [s.l.] Canadian Association of Occupational Therapists; 2012. Available from: https://www.caot.ca/pdfs/2012otprofile.pdf.

- Unsworth CA. Using a head-mounted video camera to study clinical reasoning. Am J Occup Ther. 2001;55:582–588.

- Guay M, Levasseur M, Turgeon-Londei S, et al. Support needed by home health aides in choosing bathing equipment: Exploring new challenges for occupational therapy collaboration. Work. 2013;46:263–271.

- Crocker L, Algina J. Introduction to classical and modern test theory. Orlando: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich College Publishers; 1986.

- Sim J, Wright CC. The kappa statistic in reliability studies: use, interpretation, and sample size requirements. Phys Ther. 2005;85:257–268.

- Fleiss J. Measuring nominal scale agreement among many raters. Psychol Bull. 1971;76:378–381.

- Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1977;33:159–174.

- Streiner DL, Norman GR, Cairney J. Health measurement scales: a practical guide to their development and use. 5th ed. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2014. p. 399.

- Ruest M, Bourget A, Guay M. La recherche qualitative: un vecteur d’innovation pour améliorer la fidélité inter-examinateurs d’un outil clinique. Recherches qualitatives. 2015;17:1–19.

- Ruest M, Bourget A, Delli-Colli N, et al. Recommandations to foster standardization for the completion of Algo [Recommandations pour favoriser la standardisation de la passation de l’Algo par le personnel non-ergothérapeute]. OT-NOW [Actualités ergothérapiques]. 2016;181:28–30.

- King O, Nancarrow SA, Borthwick AM, et al. Contested professional role boundaries in health care: a systematic review of the literature. J Foot Ankle Res. 2015;8:2–9.

- McMeeken J. Australia’s health workforce: implications of change. Int J Ther Rehabil. 2009;16:472–473.

- Powell JM, Kanny EM, Ciol MA. State of the occupational therapy workforce: results of a national study. Am J Occup Ther. 2008;62:97–105.

- Sanford JA, Butterfield T. Using remote assessment to provide home modification services to underserved elders. Gerontologist. 2005;45:389–398.

- Laurant M, Reeves D, Hermens R, et al. Substitution of doctors by nurses in primary care. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;2:CD001271.

- Wang LH, Chen HL, Yan HY, et al. Inter-rater reliability of three most commonly used pressure ulcer risk assessment scales in clinical practice. Int Wound J. 2015;12:590–594.

- Zwakhalen SMG, Hamers JPH, Berger MPF. The psychometric quality and clinical usefulness of three pain assessment tools for elderly people with dementia. Pain. 2006;126:210–220.

Appendix 1

Summary of clinical scenarios

Clinical scenario #1

A 69-year-old man living at home with his wife. He had central neurological disease, had diagnosed with lung cancer in 2009 and had surgery, i.e., craniotomy; client not at end of life; postoperative weakness; no cognitive impairment. Precarious balance, so he walks with a cane. Client reports having difficulty standing up in the bathtub and would like to try a grab bar. Bathroom assessment would be appreciated.

Clinical scenario #2

Needs assessment requested for 67-year-old man living with his spouse in an apartment; requested by nurse who does home visits to control Coumadin. Diagnosis: heart condition (no medical contraindication). Limited walking endurance; no assistive device for walking; fell a few months ago. Bathes with difficulty because bathroom is not adapted. Client has difficulty standing up in the bathtub.

Clinical scenario #3

Needs assessment requested for 71-year-old woman living alone at home. Diagnoses: fractured left thumb (no longer has a cast), cracks in her left side (pain), and residual back pain secondary to accidental fall. No cognitive impairment. Functional autonomy and mobility limited by pain in thumb, back and sides. No other history of falls; no assistive device for walking. Client has not had a bath since leaving hospital because she is afraid of slipping. Bathroom is not adapted.

Clinical scenario #4

Needs assessment requested for 67-year-old woman living alone at home. Diagnoses: severe bilateral gonarthrosis, has been waiting 3 years for surgery; depression secondary to constant pain; substantial deterioration (pain) in the past year; still 5–6 months’ wait for surgery in both knees (2–3 month recovery period between knees); hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes, and migraines. Always uses walker. No falls. Difficulty with any movement involving lower limbs. Activities of daily living (ADL) and household chores (IADL) difficult to do: please adapt bathroom.

Clinical scenario #5

Needs assessment requested by physician for 71-year-old man living at home with his spouse. Diagnoses: pulmonary problem (silicosis) with dyspnea, arteriosclerotic heart disease with angina, suspected neoplastic lesion in left lower lobe. Limited walking endurance; no assistive device for walking; no falls. Bathes with difficulty in shower stall: bathroom needs to be adapted.

Clinical scenario #6

Needs assessment requested for 72-year-old woman living alone at home. She needs bathing equipment since her early release from rehabilitation unit, despite good rehabilitation potential. Diagnoses: left side stroke with right hemiparesis, hypothyroidism. No cognitive impairment. Functional autonomy and mobility limited by hemiparesis. No falls; uses a cane. Family, friends and home help assist with household chores (IADL).