Abstract

There has been growing academic interest in “drinking cultures” as targets of investigation and intervention, driven often by policy discourse about “changing the drinking culture”. In this article, we conduct a critical review of the alcohol research literature to examine how the concept of drinking culture has been understood and employed, particularly in work that views alcohol through a problem lens. Much of the alcohol research discussion on drinking culture has focussed on national drinking cultures in which the cultural entity of concern is the nation or society as a whole (macro-level). In this respect, there has been a comparative tradition concerned with categorising drinking cultures into typologies (e.g. “wet” and “dry” cultures). Although overtly focused on patterns of drinking and problems at the macro-level, this tradition also points to a multifaceted understanding of drinking cultures. Even though norms about drinking are not uniform within and across countries there has been relatively less focus in the alcohol research literature on cultural entities below the level of the culture as a whole (micro-level). We conclude by offering a working definition, which underscores the multidimensional and interactive nature of the drinking culture concept.

Introduction

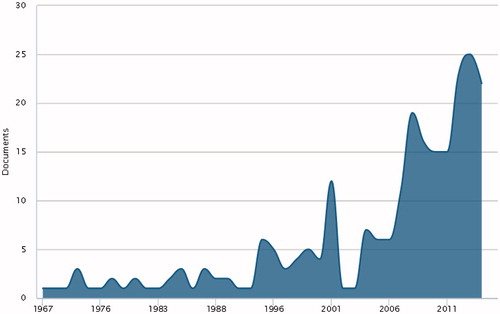

Policy documents increasingly refer to the need to “change the drinking culture” as a way of addressing problems associated with alcohol use (Her Majesty’s Government, Citation2012; Ministerial Council on Drug Strategy, Citation2006; Victorian Government, Citation2008). At least in part reflecting this, interest in drinking culture has also grown in academia. As indicated in , the number of academic journal articles in the health and social sciences that contain the term appears to have grown steadily since the early 2000s.

Figure 1. Journal articles in the SCOPUS database containing the term “drinking culture/s” between 1967 and 2014.

Although there is considerable anthropological and sociological literature on culture and drinking (e.g. see Douglas, Citation1987; Heath, Citation1987; Hunt & Baker, Citation2001), the issue of cultural aspects of drinking has also come to the fore in public health-oriented research that is concerned with the description, prevention and alleviation of health and social problems. This is not surprising given that public health has traditionally focussed on social determinants of health and upstream factors beyond the level of the individual. However, in much social research on alcohol, public health’s traditional focus on environmental and structural factors has been relegated to the background in favour of a focus on the individual (and individual responsibility), behaviour change and unhealthy lifestyles, of which alcohol consumption is seen as a part (Hunt & Baker, Citation2001).

In the public health-oriented literature on alcohol and other issues, there has been a tendency to treat “context” and causality in over-simplistic ways (Hart, Citation2015; Shoveller et al., Citation2015) and to discount the pleasures of alcohol use (Hunt & Baker, Citation2001). Given this tendency for oversimplification, we undertake a critical review of public health-oriented alcohol research (henceforth referred to as “alcohol research”) to trace how this body of work has understood and deployed the concept of “drinking culture”. Consistent with the critical review approach, we aim to “go beyond mere description of identified articles” deploying the drinking culture concept and “offer a degree of analysis and conceptual innovation … to ‘take stock’ and evaluate what is of value from the previous body of work” (Grant & Booth, Citation2009, p. 93). We do not attempt an exhaustive inventory of all the available literature on alcohol and culture, nor even all the public health-oriented literature; our concern is primarily with “the conceptual contribution of each item of included literature”, and as such this article “may provide a ‘launch pad’ for a new phase of conceptual development and subsequent ‘testing’” (Grant & Booth, Citation2009, pp. 93, 97). In particular, we trace the application of the drinking culture concept to different cultural entities at both macro- and micro-levels, and in so doing examine points of consensus and departure in terms of how drinking cultures have been understood in alcohol research. We utilise insights from anthropological and sociological literature to draw attention to potential oversimplifications, limitations and ways forward for alcohol research. In so doing, we encourage a nuanced and multi-dimensional understanding of drinking cultures and provide insights into how drinking cultures might be defined, investigated and monitored.

We show that the alcohol research literature offers little in terms of explicitly defining what is meant by the term “drinking culture”. Even in a recent review of drinking cultures, Gordon, Heim, & MacAskill (Citation2012, p. 4) stopped short of a definition, suggesting that “the question of what constitutes drinking cultures is somewhat abstract and open to interpretation”. This conceptual ambiguity has not stopped researchers from viewing drinking culture as a target of investigation or intervention. Indeed in the very next sentence, Gordon et al. go on to state that their paper identifies “key themes influencing drinking cultures” and reviews “their nature and function” (2012, p. 4). By skipping over any detailed conceptual discourse or discussion of how the study operationalises drinking culture, the concept is enacted paradoxically as commonsense and unproblematic – something that the reader intuitively understands.

On the contrary, we suggest that the widespread and unquestioned use of “drinking culture” terminology in problem-oriented alcohol research has deepened the ambiguity surrounding it and stifled conceptual development and understanding. We argue that alcohol researchers need to more clearly articulate what they mean when they refer to drinking cultures. Prior to making this argument, however, we begin with a brief overview of anthropological and sociological understandings of culture.

Culture

More than half a century after Kroeber and Kluckhohn (Citation1952) found 164 definitions of “culture” in the anthropological literature, Taras, Rowney and Steel (Citation2009) found it still true that “there is no commonly accepted definition of the word”. Taras et al. characterise culture as a “complex multilevel construct”, with shared assumptions and values as a core, and practices, symbols and artifacts as outer layers. They also emphasise stability – that a culture is shared by members of a group that it is formed over a long period, and that it is relatively stable. Jepperson and Swidler (Citation1994) suggest that for a particular cultural form, there is an underlying code of meaning and rules, there are “customs that have emerged governing it”, and there are “ideologies of talk surrounding it”.

In an exchange specifically concerned with alcohol and culture, Lemert (Citation1965) noted that in his fieldwork he had found that “group interaction and social control are far more significant than culture values in understanding of predicting … drinking” (p. 291). In reply, Mandelbaum (Citation1965) accepted this observation, adding that “I include under the term ‘culture’ those patterns of social control and of collective behaviour which are regularly used” (p. 292).

The exchange between Lemert and Mandelbaum set a pattern that has been a regular feature of discussions of alcohol and culture, emphasising social control aspects at least as much as shared values as central to the meaning of culture. Lemert (Citation1962) and Bruun (Citation1971) made strong contributions to this tradition in their typologies of cultures in terms of differences in characteristic means of controlling and minimising harm from drinking. We will discuss below the continuation of this tradition in analyses emphasising norms concerning drinking – prescriptive norms is the term in psychology – as building blocks of culture and drinking.

Drinking culture in a society as a whole

Implicit in the use of the singular “drinking culture” or in the use of “the Australian drinking culture” is a macro-sociological focus. The cultural entity of concern is the nation or society as a whole. To talk about Australian drinking culture, for instance, is to refer to rules about and patterns of drinking which are seen as specific to, and applicable across, a national culture. Thus, Australian sociologist Margaret Sargent prefaced her 1968 description of Australian “values and attitudes … [in] a group of people drinking together” with a characterisation of general “value orientations” considered to be held in Australian culture:

“tolerance (hence permissiveness to drinking), disapproval of ‘wowsers’ (hence the determination not to be a kill-joy oneself), the ideal of self-control and ‘moderation in all things’ (the main social control of drinking), conformity and belief in equality and stress on the adult male role (especially the pressure on adolescents to assume this role early)” (1968, p. 150).

In Sargent’s view, eight general orientations lay behind Australian attitudes to drinking:

“drinking as a symbol of mateship and social solidarity (especially in adult male drinking); drinking for social ease (particularly in home entertaining and cocktail parties); drinking as utilitarian (hence it is acceptable to use alcohol to ‘drown one’s sorrows’); excessive drinking as socially more acceptable as an outlet for deviance than, for example, delinquent acts or schizophrenia; drinking as virile behaviour; ‘holding one’s liquor’ as also virile; adults’ opinion that adolescent drinking should as far as possible be supervised; disapproval of heavy drinking and drunkenness in women” (1968, p. 150).

At the level of “general orientations”, many of Sargent’s generalisations are still recognisable, though much has changed in Australian society, including who does how much drinking where. However, in a complex multicultural society, there will be many subdivisions of the society where the generalisations do not apply. As Sargent intimates, the drinking culture of a society may refer and “belong” to some parts of the culture much more than to others. For instance, given the male predominance everywhere in heavier drinking, it has been remarked that what are referred to as national drinking cultures seem to mostly be referring to male drinking in the society (Gmel Room, Kuendig, & Kuntsche, Citation2007). This is important to keep in mind as we discuss drinking culture at the level of the culture as a whole. It is also important to note that the distinction between macro- and micro-scales of focus should not be viewed as mutually exclusive or necessarily in conflict, but are perhaps best seen as complementary perspectives.

The typological tradition

Concern with drinking norms and functions at the macro-level is evident in many early discussions of culture and drinking, in which academics used examples of drinking in different societies to develop typologies of the position of alcohol in cultures (Room & Mäkelä, Citation2000). These typologies are of interest because such classifications make differentiations on various dimensions. Examining the dimensions that are chosen provides insights into thinking around what is meant by a drinking culture.

A fuller catalogue of typologies identified in the literature can be found in . Many of the typologies in are focussed on drinking patterns and problems. We mention a few that are particularly noteworthy here.

Table 1. Typologies of drinking cultures identified in the literature.

Perhaps the most commonly invoked typology is the categorisation of drinking cultures into “wet” and “dry” cultures based on drinking patterns, the extent of drunkenness and drinking problems and the systems of controls that exist in a particular country (see Room & Mäkelä, Citation2000). In this framing, “wet” cultures, such as France or Italy, are characterised by high per capita consumption and of alcohol-related chronic disease and mortality, less restrictive control structures and lower rates of drunkenness. On the other hand “dry” cultures, such as Sweden or the United States (and perhaps Australia), are characterised by less frequent but heavier drinking, more restrictive control structures and higher rates of drunkenness, violence and social disruption. Although earlier typologies categorised drinking cultures on the basis of a single dimension – typically related to alcohol consumption, drunkenness or alcohol-related problems – the wet–dry typology is multi-dimensional. The “dry” label reflected that the societies it was applied to had a strong and influential temperance movement in the 19th and early 20th centuries, and scholars antagonistic to temperance tended to see the high rates of alcohol-related social problems in these cultures as resulting from the temperance history (Room, Citation1976). Other scholars pointed out, however, that the main reason temperance had been strong in these societies was the high pre-existing rates of socially disruptive drinking. The problematic drinking styles and inclinations towards heavy social control interacted with each other:

A strict system of legal and organisational control of accessibility of alcohol seems to be related to low alcohol consumption, but also to a high degree of public nuisance. The causal chain probably goes like this: A drinking culture with a large degree of highly visible, non-beneficial effects of alcohol consumption leads to a strict system of control, which somewhat reduces total consumption, which again influences and most often reduces the visible problems. But also, the system of control influences the visible problems – sometimes probably in the direction of increasing them … . In determining the amount of consumption and the problems created by consumption, I do not perceive the system of control as the independent variable. I view the system of control to be inter-related with the amount of consumption and especially with visible problems (Christie, Citation1965, p. 107).

Despite being critiqued from a number of angles (see Gordon et al., Citation2012; Room & Mäkelä, Citation2000), the wet–dry typology had the virtue of being one of the first to highlight systems of social controls as an important feature of drinking cultures, an aspect to which we will return.

Other typologies have focused on the dominant beverage consumed in a particular country (Sulkunen, Citation1976, Citation1983) to characterise these as “wine”, “beer” or “spirits” cultures. Discussions of these typologies focus not only on the type of beverage typically consumed but also on whether drinking commonly occurs with meals at home, such as in wine cultures (e.g. Italy, Greece), or whether drinking predominantly occurs in pubs and other places outside of the home, as in beer cultures. This recognition of the role of place and setting as a feature of drinking cultures is perhaps most overtly realised in Csikszentmihalyi’s (Citation1968) typology. Csikszentmihalyi describes three different types of places that exist in European countries:

Open and airy wine shops in Mediterranean cultures, with drinkers sitting in small groups around tables.

The huge darkened beer halls of Germany and Austria, with long parallel tables flanked by benches.

The stand-up bar of English pubs, with drinkers standing in a line.

What is most striking about this typology is not just the focus on places in which drinking might typically occur (e.g. a beer hall, wine shop, bar, etc.), but the detailed attention to how the drinking space feels, how it is organised in relation to the drinker and how drinkers relate to other drinkers. This relatively nuanced rendering of setting foregrounds a complex web of interactions that may occur between spatial arrangements and activities in drinking environments, individual drinkers, the drinking group and others in the drinking environment. Also of note is the absence of any mention of drinking behaviour, problems or drunkenness, which is a departure from most other typologies (d'Abbs, Citation2014).

Until Mäkelä’s discussion of “the uses of alcohol and their cultural regulation” (1983), there had been little consideration of the different uses of alcohol and meanings attributed to it as a feature of drinking cultures. Mäkelä (Citation1983) suggested that a defining feature of drinking cultures is how alcohol is used, arguing that in some cultures alcohol is used predominantly for nutrition (e.g. Italy) and in other cultures as an intoxicant (e.g. in Scandinavia). Although there are likely to be a range of further use-values – including therapeutic, recreational, social, psychoactive, etc. – Mäkelä’s discussion provokes consideration of how these uses are shaped by culture. He also considers the ways in which cultures regulate the intoxicating property of alcohol, proposing three modes of regulation:

Alcohol intoxication isolated into a sacral corner (e.g. orthodox Jews).

Alcohol intoxication confined to clearly demarcated occasions (e.g. the Camba in Bolivia).

The Scandinavian model: vacillation between “Dionysian acceptance and ascetic condemnation of drunkenness”.

As in thinking on the wet–dry typology, social control of alcohol emerges as a key feature of drinking culture in Mäkelä’s (Citation1983) discussion.

Drawing on a comprehensive review of typologies of the cultural position of alcohol, Room and Mäkelä (Citation2000) propose a basic two-dimensional typology, with possible additional features. At its most basic, this includes the regularity of drinking and the extent of drunkenness. The regularity of drinking provides an indication of the extent to which drinking is integrated in daily life – a feature of some other typologies. For instance, relatively uncommon but heavy drinking that is limited to certain religious or cultural events has been characterised as a fiesta style of drinking. However, as the authors note, a dichotomy between regular and occasional use is not enough to characterise the regularity of drinking, because in many industrialised societies many drinkers combine regular and sporadic drinking:

“A common pattern, well suited to the affluence and opportunity of the industrialised workweek, is a couple of drinks every evening, just enough to feel some effects, and a drunken “blast” on the weekend” (Room & Mäkelä, Citation2000, p. 481).

Room and Mäkelä (Citation2000) also steer attention towards the cultural meanings of drunkenness (e.g. how drunk is drunk? And what purpose does it serve?). For instance, Keane (Citation2009) shows how intoxication may be valued as “a positive and enhanced state: a form of bodily pleasure” (p. 135) in Australia, although public health discourse tends to construct and portray intoxication as risky and harmful. In this light, Room and Mäkelä (Citation2000) propose additional dimensions for understanding the cultural position of alcohol, including:

Use-values (e.g. alcohol as nutrient, alcohol as an intoxicant, etc. (Mäkelä, Citation1983)).

Expectations about behaviours while drinking or intoxicated.

The cultural position of the drinker, the drinking group and the drinking occasion.

Modes of social control of drinking.

The nature of drinking-related problems and their handling.

These additional features, together with the basic features of the regularity of drinking and the extent of drunkenness, offer a range of dimensions on which a particular cultural entity can be characterised and measured.

In a recent attempt at developing a typology, Gordon et al. (Citation2012) argue that many earlier typologies are outdated in light of the perceived homogenisation of drinking cultures across Western Europe. For instance, preference for wine is increasing in traditional beer drinking cultures (e.g. Germany), and beer consumption is increasing in places like France and Spain, which have traditionally been characterised as wine cultures. The authors provide other examples of this kind of convergence, which they suggest may be influenced by the:

“… homogenisation of lifestyles, urbanisation, greater female independence, globalisation of alcohol marketing (especially for beer, spirits and new beverages), and moves toward greater homogeneity of legislation and regulation (e.g., EU [European Union] alcohol policies)” (Gordon et al., Citation2012, p. 8).

In this light it is worth considering how globalisation has affected what have been traditionally thought of as national drinking cultures. With increased flows of people, products, information and ideas across national borders, is it possible to conceive of a national drinking culture that sits in isolation from the “global”? For instance, marketing of alcohol by multinational producers may generate flows of images and messages that are shared globally via the internet and social media (Room, Citation2010). Furthermore, scholars have noted a convergence of drinking patterns between men and women living in the USA (White et al., Citation2015) and in European countries (Beccaria & Guidoni, Citation2002; Leifman, Citation2001; Room & Mäkelä, Citation2000), and trends around young people drinking less have been described in various countries (de Looze et al., Citation2015; Pennay, Livingston, & MacLean, Citation2015). The analysis by Gordon et al. (Citation2012) prompts us to think about the extent to which phenomena of globalisation may be implicated in these recent observations (see Leifman, Citation2001; Room, Citation2010).

In what seems like a jump in their argument, Gordon et al. (Citation2012) also argue that the regularity of drinking and the extent of drunkenness dimensions proposed by Room and Mäkelä (Citation2000) could be encapsulated by a single “hedonism” dimension. They suggest that a hedonism dimension could also capture the extent to which individuals’ general lifestyles with regards to alcohol can, for example, be described as hedonistic (or ascetic).

Proposing a single dimension to characterise a culture’s drinking style, with “ascetic” at one end of it, seems reminiscent of old temperance-movement framings, with an implicit assumption that drinking will lead to intoxication. The dimension’s label assumes that both drinking and drunkenness are inherently hedonistic and thus opposed to dominant social discourses of restraint and moderation (Hunt & Barker, Citation2001); but alcohol’s use-values are not limited to pleasure. Alongside their “hedonism” dimension, Gordon et al. (Citation2012) propose two other dimensions to characterise “drinking cultures”: function (“inter/intrapersonal, ritual, intoxication”) and modes of social control. But the presentation of their typology does not go beyond these minimal characterisations, and the authors make no attempt to classify any societies on the dimensions.

The numerous instances where Room and Mäkelä (Citation2000) point to exceptions to general correlational patterns highlight the difficulty of pigeonholing national drinking cultures into discrete categories. For instance, drinking in Mediterranean or wine-drinking cultures is strongly associated with meals, and is associated with “less officially recognised social disruption than elsewhere” (2000, p. 478). However, the notion of this seemingly idyllic kind of drinking culture (or a singular homogeneous culture) is rendered problematic in light of other literature, for example, about men drinking in the tavernas of Greece rather than in the home (Gefou-Madianou, Citation1992), or about drunkenness that also occurs among young people in wine drinking cultures (Beccaria & Guidoni, Citation2002), even if to a lesser extent. What this suggests is that at a societal level drinking cultures are not homogeneous. For the society as a whole, there may be recognisable characteristics that differ from patterns elsewhere – as in Sargent’s (Citation1968) characterisation of Australian drinking culture quoted above – but there are often also divergent features in subcultures or social groups, and often also in culturally defined “time out” periods.

Although we can point to flaws in each individual typology and in the way in which typologies are developed, the typological literature produces some useful insights. First, as the more nuanced typologies suggest, the drinking culture concept is not just about patterns of drinking (e.g. rates of alcohol use, types of beverages consumed) or problems (e.g. extent of drunkenness, alcohol-related mortality or morbidity) that exist in a cultural entity, but also encompasses meanings and use-values, the settings and places in which drinking occurs, and how drinking is controlled or regulated within a society.

Normative perspectives

A perspective which encompasses both the aspect of customs and expectations about drinking and the aspect of social control and adverse responses to drinking behaviour is the concept of norms. Room (Citation1975) argued that norms are the crucial building blocks lying behind the consumption patterns that had been the primary focus of previous discussions. Defining a norm as “a cultural rule or understanding affecting behaviour, which is to a greater or lesser degree enforced by sanctions” (1975, p. 359), Room notes that a norm is cultural in the sense that it is “not a property of an individual or a private understanding between people interacting with one another, but is a relatively permanent rule shared by a class of individuals who may not ever have met each other” (1975, pp. 359–360). In this respect a norm can apply at the level of the whole culture, a well-defined subculture or a less well-defined “social world” of persons with common interests or status. In Room’s usage, a norm can be an understanding held in common by “a group of people about what is appropriate behaviour” (1975, p. 359), but it can also take the form of a law or official regulation. Including formal rules as a kind of norms potentially brings the tools of government into the fold of drinking cultures (e.g. regulation, policy, etc.).

The typological tradition’s emphasis on social control as a dimension of drinking cultures is reflected in Room’s (Citation1975) allusion to “sanctions”, which he suggests can be formal and severe (e.g. a fine, getting thrown out of a bar, being arrested and charged, etc.) or can be informal and transitory (e.g. a lifted eyebrow, a disapproving look, etc.). However, norms can act not only as mechanisms to limit behaviour, but also to encourage particular behaviours (e.g. norms about buying rounds of drinks). In contrast to the focus on “drinking” behaviour and patterns in the typological work, Room highlights that most norms are directed at behaviour during or after drinking.

A major point that Room (Citation1975) makes is that norms governing drinking and associated behaviour differ “both according to the social situation – time and place and occasion – and according to the individual status on various social differentiations” (p. 361). Examples of norms include the appropriate age to be a drinker, situations in which it is appropriate to drink (e.g. not at work), traditional expectations about women drinking less than men or older people drinking less than young people. Although drinking cultures have often been depicted implicitly as aggregates of individual actions carried out in certain prescribed ways (e.g. in wine-drinking cultures there will be less drunkenness, in dry countries there will be more drunkenness, etc.), Room directs our attention to the social, relational and emergent qualities of drinking behaviour and drinking problems, arguing that these “arise out of the interaction between the drinker’s behaviour and the various responses of others” (1975, p. 360).

Dimensions of focus in studies of drinking cultures at a macro-level

In order to obtain an indication of the dimensions of drinking culture alcohol researchers have focused on recently, we identified peer-reviewed articles in health and social science journals that included the term “drinking culture” between 2010 and 2015. This illustrated that the way in which drinking cultures have been researched at the level of the culture as a whole (the macro-level) has been similar, irrespective of the tradition in which the study might be located. Change over time analyses and cross-national comparisons have predominated. As illustrated in , most studies tend to be quantitative, with many drawing on general population survey data.

Table 2. Recent studies on drinking culture at a macro-level, 2010–2015.

As can be seen in , studies tend to focus on a limited number of dimensions of drinking culture. In studies examining drinking patterns, a focus on intoxication and alcohol-related problems is common (e.g. Härkönen, Törrönen, Mustonen, & Mäkelä, Citation2013; Loughran, Citation2010; Mäkelä, Tigerstedt, & Mustonen, Citation2012; Mustonen, Mäkelä, & Lintonen, Citation2014; Raitosalo et al., Citation2011; Stickley, Jukkala, & Norstrom, Citation2011). For instance, in their study of changes to Finnish drinking culture between 1968 and 2008 using general population survey data, Mäkelä et al. (Citation2012) note that Finland has become a “wet” drinking culture, although sporadic intoxication (primarily on weekends and evenings) still maintains an important role of the drinking culture. Many of the studies focus on young people (e.g. Beccaria & Prina, Citation2010; Bye & Rossow, Citation2010; Hellman & Rolando, Citation2013; Loughran, Citation2010; Petrilli et al., Citation2014; Rolando, Citation2014; Rolando, Beccaria, Tigerstedt, & Törrönen, Citation2012), reflecting a conceptualisation of youth drinking as in itself a problem, and ignoring the range of other frames in which the material might be analysed. In addition, with the exception of a few studies (e.g. Härkönen et al., Citation2013; Mäkelä et al., Citation2012; Mustonen et al., Citation2014; Raitasalo et al., Citation2011), the role of place, occasions and the settings in which drinking occurs has been largely neglected in recent alcohol research. Similarly, use-values and modes of social control have been understudied.

The dominant research interest in problem-focussed dimensions of drinking culture at a macro-level might be seen as reflecting a public policy discourse about drinking culture, in which changing the drinking culture is viewed as a way of preventing and minimising harms (e.g. Victorian Government, Citation2008), often presented as an alternative solution to social problems that do not require government interference in the market.

A drawback of focussing on a limited number of dimensions of drinking culture at a macro-level is that we are unable to understand how these dimensions interact in different circumstances and apply to different population groups. This may lead to an overly simplistic understanding of drinking culture as acting in predictable ways, with predictable effects, irrespective of the other forces that may be operating in any given drinking situation.

It should also be noted that the majority of studies of drinking culture at the macro-level focus on European countries, with Finland and Italy being particularly prominent. Given observations of shifting drinking patterns in Finland and Italy (e.g. Allamani & Prini, Citation2007; Mäkelä et al., Citation2012), it is understandable that researchers would be interested in why these changes have occurred. The applicability of findings on drinking culture from Europe to other countries is unclear.

Summary of the critique of the understanding of the drinking culture concept in alcohol research

As we have illustrated thus far, there are a number of limitations in the way “drinking culture” has been understood and studied in alcohol research, and thus good reason to consider potentially novel ways of conceptualising drinking cultures. There is a well-established anthropological and sociological criticism of alcohol research understandings of drinking culture highlighted thus far (see Douglas, Citation1987; Heath, Citation1987; Hunt & Baker, Citation2001). This has been most recently summarised by d’Abbs (Citation2014), who, like Room and Mäkelä (Citation2000), argues for a more nuanced understanding of drinking cultures, making three key points.

First, the emphasis on problems associated with drinking patterns and intoxication in discussions around drinking culture has obscured some of the meanings and practices associated with alcohol use that are culturally significant. As we have suggested, much of the research discussed on drinking cultures can be situated within a public health discourse, which views particular levels of alcohol use as “risky” and “harmful” irrespective of the context and purposes of use. As such, “drinking culture” as a determinant or mediator of alcohol use is viewed as a target for monitoring and intervention. The problem with this discourse is that it oversimplifies drinking cultures and does not take into account the benefits that alcohol use may confer (e.g. pleasure, social connection, intimacy, cultural belonging, cultural capital, etc.) and the way it is used in cultural practices (e.g. celebrations, religious occasions, etc.). Indeed there is a considerable body of sociological and anthropological work in particular that argues for the need to include pleasure in analyses of individual and collective decision-making about using alcohol and other drugs (e.g. Bancroft, Zimpfer, Murray, & Karels, Citation2014; Bunton, Citation2011; Duff, Citation2008; Moore & Measham, Citation2012; O'Malley & Valverde, Citation2004; Ritter, Citation2014). Without appreciation of the pleasure of alcohol use and other factors, attempts to change drinking cultures are likely to be unsuccessful.

Second, d’Abbs (Citation2014) notes that there is a tendency for the literature around drinking culture to enact drinking culture as “a stable sociological entity, anchored to a delimited geographical or social space” (p. 4). But in general thinking about cultures, this is increasingly seen as a problematic view, with cultures coming to be seen rather “as networks of meanings that are continuously being renegotiated and reconstituted rather than transmitted” (Hannerz, Citation1992 cited in d'Abbs, Citation2014, p. 4). In this context, d’Abbs (Citation2014) urges us to move away from viewing drinking culture as a static entity with prescriptive norms that are “linked to sanctions and rewards designed to foster conformity and discourage deviance” (p. 4). Drinking cultures do not necessarily produce consistent and predictable behaviour, independent of the other contextual forces in which they are entangled in a given situation. Rather, there is a need to examine how drinking culture manifests in relation to other actors, use-values, practices and settings, in a given local situation. This necessitates the need for a shift in examining drinking cultures from the macro to the micro.

Third, there is another good reason for this shift, as d’Abbs (Citation2014) notes. The notion of a national drinking culture assumes that the nation is a homogeneous entity. But patterns of, and norms about, drinking as with other social behaviours, are not uniform within a single country (Fortin, Bélanger, & Moulin, Citation2015). In fact, there are often great variations, which in part reflect variations in norms about drinking between different subgroups in the population. As d’Abbs (Citation2014) argues, there may be many drinking cultures within a society, necessitating a micro-level focus, below the level of the culture as a whole. We will draw on such insights in understanding drinking culture from anthropology and sociology later when we propose a working definition.

Below the culture as a whole

“Subcultures” (e.g. Hall & Jefferson, Citation1976), “contracultures” (or “countercultures”; e.g. Yinger, Citation1960), “subworlds”, “social worlds” (e.g. Unruh, Citation1980), “scenes” (e.g. Moore, Citation2004; Straw, Citation1991), and “neo-tribes” (e.g. Bennett, Citation1999) are among the array of terms used to describe cultural entities below the level of the culture as a whole, with each term offering a different meaning and frame of reference for “sub-entities”. In general, “subculture” (and related terms such as “contraculture” or “counterculture”) are used to refer to relatively holistic cultural entities that engross a good deal of members’ lives and times and which often provide a master identity for members. Terms like “social worlds” or “scenes” tend to indicate cultural entities more limited in their claim on participants’ lives, often referring to situations where members participate in several different “worlds” or “scenes”, and move back and forth between them as a matter of course. It should be recognised that there is no clear agreement on terminology or how best to operationalise cultural entities in terms of understanding their uniqueness, fluidity, degree of completeness or influence.

Despite the lack of agreement around terminology, sub-societal cultural groupings (e.g. subcultures, social worlds, scenes) tend to be both objects of self-conscious identification by members, and to be recognised and assigned a group identity from members of the larger society. The distinctions in norms between the cultural group and the larger society are often recognised by those outside the grouping, and are always recognised by those on the inside. For some sub-societal cultural entities, membership is considerably bounded by stable and largely assigned characteristics of the individual such as ethnicity, social class or geographic residence – ethnic subcultures or occupational subcultures, for instance. On the other hand, there are subcultures or social worlds where becoming a member is to a considerable extent a matter of choice and style – cultural entities such as rap or house music aficionados, graffiti artists, skateboarders or athletic “jocks”, to cite some social worlds which have been studied (e.g. Bennett, Citation1999; Eckert, Citation1989; Thornton, Citation1995; Hall & Jefferson, Citation1976). However, “choice” and “assigned characteristics” are often both involved: for instance in their fieldwork interviews with young people in the UK, McCulloch et al. (Citation2006, p. 539) show how “young people’s subcultural styles and identities are closely bound up with social class”, which is largely assigned. In any case, rules about drinking and associated behaviour – including norms about limiting drinking or not drinking – are often a part of the normative structure of the subculture or social world, whether the entity is defined in terms of assigned characteristics or in terms of members’ shared interests.

In the field of ethnography, the cultural entity – the scene, social world, or subculture – is studied through particular sets of people in regular interaction with other as they act out their group participation. To qualify as a cultural entity, it can be argued that the group’s norms and practices must extend beyond a particular face-to-face group, so that even members of the grouping who have not met each other will be able to recognise a common set of norms.

There are various examples of face-to-face groups operating between social worlds or scenes (for example see: Chatterton & Hollands, Citation2003; Grace, Moore, & Northcote, Citation2009; Jayne, Holloway, & Valentine, Citation2006; Measham & Brain, Citation2005; Roberts, Citation2015; Pennay, Beccaria, Prina, & Rolando, Citation2012; Valentine, Holloway, Knell, & Jayne, Citation2008; Winlow & Hall, Citation2006), and of the way in which these worlds have their own style of communication and set of activities although these studies do not usually adopt a problem perspective.

This previous research has highlighted among other things the fluid nature of scenes, with individuals moving between different groups and changing their alcohol and substance use practices accordingly. It has also highlighted the different norms and drinking practices that operate across groups, settings and gender. This is also a point that Hutton, Wright and Saunders (Citation2013) make in relation to young women’s drinking cultures in New Zealand, albeit in terms of identifying risky and pleasurable places in order to inform harm reduction interventions.

One type of subpopulation on which there has been a substantial literature on drinking norms is ethnic groups in multicultural societies. Studies of drinking in particular cultures were initiated in the mid-1940s by US researchers, who paid attention to the drinking practices of cultural and ethnic groups such as the Italians, Irish and Jews (see Room, Citation1985). Although some of these studies were concerned with national cultures, often the study focused on how ethnic drinking practices operated in an American context (Greeley & McCready, Citation1978). Some of these studies distinguished between patterns and meanings in the original national culture and the ethnic group in a multicultural society; for example, in Stivers’ study of Irish-American drinking patterns, he noted: “In Ireland, drink was largely a sign of male identity; in America it was a symbol of Irish identity” (Stivers, Citation1976, p. 129). More recent studies have explored the use of alcohol and risk factors for alcohol-related harm among migrant communities (e.g. Gutmann, Citation1999; Mills & Caetano, Citation2012). In one such study, Gutmann (Citation1999) discusses the “migratory and alcohol consumption experiences” of Latin American born individuals residing in the USA and critiques the use of the term “acculturation” as a means to explain changes in drinking practices among new migrants. As part of this discussion he provides the following reflection on ethnic identity, drinking patterns and migration:

“Cultures and cultural quantities like ethnicity are created anew as much as they are inherited from the past. Thus, for immigrants from Latin America, attitudes towards drinking and actual drinking behaviour do not simply reflect what people ‘left behind’ versus what they ‘find’ (and ‘move toward’) in the United States. Ethnic identity can also intensify following migration, and as part of this process alcohol use and abuse can undoubtedly change” (Gutmann, Citation1999, p. 182).

Often, indeed, the drinking behaviour of an ethnic group in a multicultural environment can be interpreted as an element in a performance before other elements of the society (Room, Citation2005; Stivers, Citation1976). What is evident in these examples is that each scene or social world has different norms, customs, sanctions and use-values associated with alcohol, and these often differ from those identified in macro-level typologies of drinking culture.

Making sense of different cultural entities and their interactions

Cultural entities, whether at the whole-culture level or as subordinate groupings, should not be assumed to be unchanging and unchangeable, nor are they necessarily in conflict. With this in mind, we propose it is important to consider what the layers of influence are surrounding multiple entities and the culture as a whole and whether there is a hierarchy. Questions such as this must be considered as we untangle and make sense of complex social and cultural arrangements.

To better understand the way in which drinking cultures operate it is important to understand how subcultures or social worlds interact with the larger culture. This is a common topic in studies of contracultures, but is often neglected in studies of more integrated cultural entities. Room (Citation1976) argues that there is a loose social world of heavy drinkers in complex societies like the USA or Australia. Members of this world share an understanding of a set of norms that support and require heavy drinking in particular situations – for instance, norms about drinking etiquette and buying rounds in a pub or club. These norms may vary from the norms of the general culture, but heavy drinkers and the general population co-exist relatively peacefully. The means through which the social world of drinkers co-exists with the general population norms is through what Room calls “an implicit compromise policy of enclaving”. Enclaving the social world of heavy drinking is “an agreement that the world … will be tolerated so long as it conducts itself only within certain boundaries” (1976, p. 363). This agreement needs to be maintained by both sides (e.g. bars and their patrons keep what goes on inside the bar from being too visible to others, etc.).

Room (Citation1975) argues that social problems of drinking arise more from a conflict of norms than from individual acts of transgression, which are more likely to be dealt with by informal non-institutionalised actors (e.g. family, friends, neighbours, strangers, etc.). He identifies two types of conflicts of norms that can occur in relation to drinking:

Sequence problems or problems of transition – where we find ourselves intoxicated in a situation where it is no longer appropriate (e.g. wrong place at the wrong time). For instance, this can occur when a bar closes and an intoxicated person finds themselves in the street or the partygoer finds herself or himself responsible for driving home. This can be solved by changing the normative structure of one or other of the sequenced situations or allowing more time between the two situations.

Boundary problems – in which the boundary of the zone in which heavy drinking is normative is breached either accidentally or deliberately by those “outside” or “inside” the boundary. The agreement of accommodation implied by enclaving becomes unstable, and people in the social world of heavy drinking may try to extend its reach whereas those in the general culture (e.g. moral entrepreneurs, law and order advocates or public health advocates), may seek to hem the social world in (e.g. contests around public drinking). Boundary problems can be resolved through strengthening the insulation surrounding the enclaves, as well as changing the normative structures on one side (e.g. smoking outside if people object to smoking indoors, etc.).

Room notes that, although efforts to control heavy drinking social worlds may reduce consumption, they may also sometimes increase the visibility of drinking-related problems, which in turn can result in resistance from members of the social worlds under observation. The concepts of “enclaving”, “sequence problems” and “boundary problems” provide useful ways of thinking about the way in which micro- and macro-level drinking cultures may interact, and how conflicts over drinking norms might be resolved.

Conclusion: ways forward

As we have articulated throughout, much of the alcohol research on drinking cultures has focussed narrowly on alcohol consumption and alcohol problems, obscuring the multidimensional nature of drinking cultures. This has essentially isolated alcohol consumption and problems from the network of other possible interactional and cultural factors involved. However, as Duff notes, research needs to focus on the way in which alcohol consumption “is enacted, performed or ‘entrained’ within a wider network of social, material and affective forces” (Duff, Citation2013, p. 267) in different occasions. Similarly, we have identified a need to acknowledge the multiplicity of “drinking cultures” at different scales (macro and micro) and the way that these might interact and be configured in different circumstances.

In the light of the preceding analyses and dimensions of drinking culture highlighted in the alcohol research literature, we offer here a summary characterisation of what “drinking cultures” can be taken to mean:

Drinking cultures are generally described in terms of the norms around patterns, practices, use-values, settings and occasions in relation to alcohol and alcohol problems that operate and are enforced (to varying degrees) in a society (macro-level) or in a subgroup within society (micro-level). Drinking culture also refers to the modes of social control that are employed to enforce norms and practices. Drinking culture may refer to the aspects concerned with drinking of a cultural entity primarily defined in terms of other aspects, or may refer to a cultural entity primarily defined around drinking. Drinking cultures are not homogeneous or static but are multiple and moving. As part of a network of other interacting factors (e.g. gender, age, social class, social networks, individual factors, masculinity, policy, marketing, global forces, place, etc.), drinking culture is thought to influence when, where, why and how people drink, how much they drink, their expectations about the effects of different amounts of alcohol, and the behaviours they engage in before, during and after drinking. The degree and nature of the influence that drinking cultures have on individuals is not inevitable but will depend on the configuration of factors in play in any given situation, and the nature of the relationships between the culture as a whole and smaller cultural entities as they affect the individual.

We acknowledge that attempting to define “drinking cultures” is a potentially fraught exercise and that there is other sociological and anthropological work that would be useful in the conceptualisation of drinking cultures, but we offer this “working definition” as a way of stimulating further conceptual thought and discussion amongst alcohol researchers and others. We also propose this working definition as a first step in thinking about how alcohol researchers might study drinking cultures in their complexity and possible questions such studies might pose. For instance, our definition foregrounds multiple dimensions that researchers might investigate, including norms about who can drink, patterns (how frequently and how much is it acceptable to drink?), practices (what is acceptable/unacceptable practice and behaviour during and after drinking?), alcohol problems (what constitutes an alcohol-related problem and how should such a problem be handled?), settings (where is it appropriate to drink and where is it not? How are drinking spaces configured/inhabited? How should people move between spaces/places when they are drinking or have finished drinking?), occasions and times (when is it acceptable to drink or get drunk?), use-values (what does alcohol use mean? What purpose does it serve?), and modes of social control (what are the informal and formal sanctions that are in place when norms are breached?). We acknowledge that anthropologists and sociologists readily ask many of these questions, and that alcohol researchers are already asking some of these questions or are attending to one dimension of drinking culture or another. However, we suggest that it would be valuable for alcohol researchers to attend to these simultaneously if we are to investigate drinking cultures in their complexity.

As our definition attends to the multi-dimensional nature of drinking cultures and their interactions, researchers might also explore how micro- and macro-level drinking cultures relate, and how drinking culture acts in combination with a range of other factors to produce effects. For instance, we might ask what influence does drinking culture have in different circumstances, occasions, settings and groups, and why is it more or less influential in particular circumstances than others? Addressing these questions may more productively inform attempts at changing drinking cultures.

Policy makers have increasingly argued that there is a need to “change the drinking culture”, and have sought to understand the drivers or impacts of changes in the drinking culture. But, given the conceptual ambiguity surrounding the concept, it is unclear what exactly needs to be changed. This article represents an attempt to conceptualise drinking cultures with reference to the relevant alcohol research literature and in light of insights from broader sociological and anthropological work. In so doing we have highlighted the multiple and multifaceted nature of drinking cultures at both macro- and micro-levels. Engaging with such conceptual complexities will hopefully sharpen attempts at investigating and changing drinking cultures. However, further empirical work in diverse contexts is needed to better understand drinking cultures, their interactions and their entanglement with other factors. Given that the majority of alcohol research discussed focuses on drinking cultures in European and Anglophone countries, there is a particular need for research outside these countries. Furthermore, additional work is necessary to examine policy makers’ understandings of drinking culture and how these compare with academic and “lay” definitions of drinking cultures.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank VicHealth for funding the project that was the basis for this paper. In particular, we would like to thank Emma Saleeba and Sean O’Rourke for their helpful feedback throughout the project.

Declaration of interest

M.L. and A.P. are supported by NHMRC Early Career Fellowships (1053029 and 1069907, respectively). This work was supported by a contract from the Victorian Health Promotion Foundation (VicHealth) and by a grant from the Foundation for Alcohol Research and Education (FARE).

References

- Ahlström-Laakso, S. (1976). European drinking habits: A review of research and some suggestions for conceptual integration of findings. In Everett, M., Waddell, J., & Heath, D. (Eds.), Cross-cultural approaches to the study of alcohol. An interdisciplinary perspective (pp. 119–132). The Hague and Paris: Mouton

- Allamani, A., & Prini, F. (2007). Why the decrease in consumption of beverages in Italy between the 1970s and the 2000s? Shedding light on an Italian mystery. Contemporary Drug Problems, 34, 187–197. doi: 10.1177/009145090703400203

- Allamani, A., Voller, F., Pepe, P., Baccini, M., Massini, G., & Cipriani, F. (2014). Italy between drinking culture and control policies for alcoholic beverages. Substance Use and Misuse, 49, 1646–1664. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2014.913386

- Bales, R.F. (1946). Cultural differences in rates of alcoholism. Quarterly Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 6, 480–499

- Bancroft, A., Zimpfer, M.J., Murray, O., & Karels, M. (2014). Working at pleasure in young women’s alcohol consumption: A participatory visual ethnography. Sociological Research Online, 19, 20. doi: 10.5153/sro.3409

- Beccaria, F., & Guidoni, O.V. (2002). Young people in a wet culture: Functions and patterns of drinking. Contemporary Drug Problems, 29, 305–336. doi: 10.1177/009145090202900205

- Beccaria, F., & Prina, F. (2010). Young people and alcohol in Italy: An evolving relationship. Drugs: Education, Prevention and Policy, 17, 99–112. doi: 10.3109/09687630802291703

- Bennett, A. (1999). Subcultures or neo-tribes? Re-thinking the relationship between youth, style and musical taste. Sociology, 33, 599–617. doi: 10.1177/S0038038599000371

- Bunton, R. (2011). Permissable pleasures and alcohol consumption. In Bell, K., McNaughton, D., & Salmon, A. (Eds.), Alcohol, tobacco and obesity: Morality, mortality and the new public health (pp. 93–106). Abingdon: Routledge

- Bruun, K. (1971). Implications of legislation relating to alcoholism and drug dependence. In Kiloh, L.G., & Bell, D.S. (Eds.), Proceedings, 19th International Congress on Alcoholism and Drug Dependence (pp. 175–181). Australia: Butterworths

- Bye, E.K., & Rossow, I. (2010). The impact of drinking pattern on alcohol-related violence among adolescents: An international comparative analysis. Drug and Alcohol Review, 29, 131–137. doi: 10.1111/j.1465-3362.2009.00117.x

- Chatterton, P., & Hollands, R. (2003). Urban nightscapes: Youth cultures, pleasure spaces and corporate power. London: Routledge

- Christie, N. (1965). Scandinavian experience in legislation and control. In Boston University (Ed.), National Conference on Legal Issues in Alcoholism and Alcohol Usage (pp. 101–122). Boston: Boston University Law-Medicine Institute

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1968). A cross-cultural comparison of some structural characteristics of group drinking. Human Development, 11, 201–216. doi: 10.1159/000270607

- d'Abbs, P. (2014). Reform and resistance: Exploring the interplay of alcohol policies with drinking cultures and drinking practices. Paper presented at the Kettil Bruun Society Thematic Conference on Alcohol Policy Research, Melbourne, Australia

- de Looze, M., Raaijmakers, Q., ter Bogt, T., Bendtsen, P., Farhat, T., Ferreira, M. … Pickett, W. (2015). Decreases in adolescent weekly alcohol use in Europe and North America: Evidence from 28 countries from 2002 to 2010. European Journal of Public Health, 25(Suppl. 2), 69–72. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckv031

- Douglas, M. (1987). A distinctive anthropological perspective. In Douglas, M. (Ed.), Constructive drinking: Perspectives on drink from anthropology (pp. 3–15). New York/Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

- Duff, C. (2008). The pleasure in context. International Journal of Drug Policy, 19, 384–392. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2012.12.009

- Duff, C. (2013). The social life of drugs. International Journal of Drug Policy, 3, 167–172. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2007.07.003

- Eckert, P. (1989). Jocks and burnouts: Social categories and identities in the high school. New York and London: Teachers College Press

- Fortin, M., Bélanger, R.E., & Moulin, S. (2015). Typology of Canadian alcohol users relationships between use, context, and motivation to drink in the definition of drinking profiles. Contemporary Drug Problems. . [Epub ahead of print]. doi: 10.1177/0091450915600119

- Gefou-Madianou, D. (1992). Exclusion and unity, retsina and sweet wine: Comensality and gender in a Greek agrotown. In Gefou-Madianou, D. (Ed.), Alcohol, gender and culture (pp. 1–34). New York: Routledge

- Gmel, G., Room, R., Kuendig, H., & Kuntsche, S. (2007). Detrimental drinking patterns: Empirical validation of the pattern values score of the Global Burden of Disease 2000 study in 13 countries. Journal of Substance Use, 12, 337–358. doi: 10.1080/14659890701249624

- Gordon, R., Heim, D., & MacAskill, S. (2012). Rethinking drinking cultures: A review of drinking cultures and a reconstructed dimensional approach. Public Health, 126, 3–11. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2011.09.014

- Grace, J., Moore, D., & Northcote, J. (2009). Alcohol, risk and harm reduction: Drinking amongst young adults in recreational settings in Perth. Perth: Curtin University of Technology

- Grant, M.J., & Booth, A. (2009). A typology of reviews: An analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Information & Libraries Journal, 26, 91–108. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x

- Greeley, A.M., & McCready, W.C. (1978). Part two: A preliminary reconnaissance into the persistence and explanation of ethnic subcultural drinking patterns. Medical Anthropology, 2, 31–51. doi: 10.1080/01459740.1978.9986961

- Gutmann, M.C. (1999). Ethnicity, alcohol and acculturation. Social Science and Medicine, 48, 173–184. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(98)00325-6

- Hall, S., & Jefferson, T. (1976). Resistance through rituals: Youth subcultures in post-war Britain. New York: Holmes & Meier Publishers

- Hannerz, U. (1992). The global ecumene as a network of networks. In: Kuper, A. (Ed.), Conceptualizing society (pp. 34–56). London: Routledge

- Härkönen, J.T., Törrönen, J., Mustonen, H., & Mäkelä, P. (2013). Changes in Finnish drinking occasions between 1976 and 2008 – The waxing and waning of drinking contexts. Addiction Research and Theory, 21, 318–328. doi: 10.3109/16066359.2012.727506

- Hart, A. (2015). Assembling interrelations between low socioeconomic status and acute alcohol-related harms among young adult drinkers. Contemporary Drug Problems, 42, 148–167. doi: 10.1177/0091450915583828

- Heath, D.B. (1987). A decade of development in the anthropological study of alcohol use: 1970–1980. In Douglas, M. (Ed.), Constructive drinking: Perspectives on drinking from anthropology (pp. 16–69). New York/Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

- Hellman, M., & Rolando, S. (2013). Collectivist and individualist values traits in Finnish and Italian adolescents' alcohol norms. Drugs and Alcohol Today, 13, 51–59. doi: 10.1108/17459261311310853

- Her Majesty’s Government. (2012). The Government’s alcohol strategy. London: Her Majesty’s Government

- Hunt, G., & Barker, J.C. (2001). Socio-cultural anthropology and alcohol and drug research: Towards a unified theory. Social Science & Medicine, 53, 165–188. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(00)00329-4

- Hutton, F., Wright, S., & Saunders, E. (2013). Cultures of intoxication: Young women, alcohol, and harm reduction. Contemporary Drug Problems, 40, 451–480. doi: 10.1177/009145091304000402

- Keane, H. (2009). Intoxication, harm and pleasure: An analysis of the Australian National Alcohol Strategy. Critical Public Health, 19, 135–142. doi: 10.1080/09581590802350957

- Jayne, M., Holloway, S.L., & Valentine, G. (2006). Drunk and disorderly: Alcohol, urban life and public space. Progress in Human Geography, 30, 451–468. doi: 10.1191/0309132506ph618oa

- Jepperson, R., & Swidler, A. (1994). What properties of culture should we measure? Poetics, 22, 359–371. doi: 10.1016/0304-422X(94)90014-0

- Kroeber, A.L., & Kluckhohn, C. (1952). Culture: A critical review of concepts and definitions. New York: Vintage Books

- Leifman, H. (2001). Homogenisation in alcohol consumption in the European Union. Nordic Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 18, 15–30

- Lemert, E.M. (1965). Comment on Mandelbaum’s article ‘Alcohol and culture’. Current Anthropology, 6, 291

- Lemert, E.M. (1962). Alcohol, values and social control. In Pittman, D.J., & Snyder, C.R. (Eds.), Society, culture and drinking patterns (pp. 553–571). New York & London: Wiley

- Loughran, H. (2010). Eighteen and celebrating: Birthday cards and drinking culture. Journal of Youth Studies, 13, 631–645. doi:10.1080/13676261003801721

- MacAndrew, C., & Edgerton, R.B. (1969). Drunken comportment: A social explanation. Chicago: Aldine

- Mäkelä, K. (1983). The uses of alcohol and their cultural regulation. Acta Sociologica, 26, 21–31. doi: 10.1177/000169938302600102

- Mäkelä, P., Tigerstedt, C., & Mustonen, H. (2012). The Finnish drinking culture: Change and continuity in the past 40 years. Drug and Alcohol Review, 31, 831–840. doi: 10.1111/j.1465-3362.2012.00479.x

- Mandelbaum, D.G. (1965). Reply [to comments on his ‘Alcohol and culture’]. Current Anthropology, 6, 292–293

- McCulloch, K., Stewart, A., & Lovegreen, N. (2006). ‘We just hang out together’: Youth cultures and social class. Journal of Youth Studies, 9, 539–556. doi: 10.1080/13676260601020999

- Measham, F., & Brain, K. (2005). ‘Binge’drinking, British alcohol policy and the new culture of intoxication. Crime, Media, Culture, 1, 262–283. doi: 10.1177/1741659005057641

- Mills, B.A., & Caetano, R. (2012). Decomposing associations between acculturation and drinking in Mexican Americans. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 36, 1205–1211. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2011.01712.x

- Ministerial Council on Drug Strategy. (2006). National Alcohol Strategy 2006–2009. Canberra: Ministerial Council on Drug Strategy

- Mizruchi, E.H., & Perrucci, R. (1970). Prescription, proscription and permissiveness: Aspects of norms and deviant drinking behavior. New Haven: College and University Press

- Moore, D. (2004). Beyond subculture in the ethnography of illicit drug use. Contemporary Drug Problems, 31, 181–212. doi: 10.1177/009145090403100202

- Moore, K., & Measham, F. (2012). Impermissible pleasures in UK leisure: Exploring policy developments in alcohol and illicit drugs. In Jones, C., Barclay, E., & Mawby, R.I. (Eds.), The problem of pleasure: Leisure, tourism and crime (pp. 62–76). London: Routledge

- Mustonen, H., Mäkelä, P., & Lintonen, T. (2014). Toward a typology of drinking occasions: Latent classes of an autumn week's drinking occasions. Addiction Research and Theory, 22, 524–534. doi: 10.3109/16066359.2014.911845

- O'Malley, P., & Valverde, M. (2004). Pleasure, freedom and drugs: The uses of ‘pleasure' in liberal governance of drug and alcohol consumption. Sociology, 38, 25–42. doi: 10.1177/0038038504039359

- Partanen, J. (1991). Sociability and intoxication: Alcohol and drinking in Kenya, Africa, and the modern world (Vol. 39). Helsinki: Finnish Foundation for Alcohol Studies

- Pennay, A. (2012). Carnal pleasures and grotesque bodies: Regulating the body during a “big night out” of alcohol and party drug use. Contemporary Drug Problems, 39, 397–428. doi: 10.1177/009145091203900304

- Pennay, A., Livingston, M., & MacLean, S. (2015). Young people are drinking less: It’s time to find out why. Drug and Alcohol Review, 34, 115–118. doi: 10.1111/dar.12255

- Petrilli, E., Beccaria, F., Prina, F., & Rolando, S. (2014). Images of alcohol among Italian adolescents: Understanding their point of view. Drugs: Education, Prevention and Policy, 21, 211–220. doi: 10.3109/09687637.2013.875128

- Pittman, D.J. (1967). International overview: Social and cultural factors in drinking patterns, pathological and nonpathological. In Pittman, D.J. (Ed.), Alcoholism (pp. 3–20). New York: Harper & Row

- Raitasalo, K., Holmila, M., & Mäkelä, P. (2011). Drinking in the presence of underage children: Attitudes and behaviour. Addiction Research and Theory, 19, 394–401. doi: 10.3109/16066359.2011.560693

- Ritter, A. (2014). Where is the pleasure? Addiction, 109, 1587–1588

- Roberts, M. (2015). ‘A big night out’: Young people’s drinking, social practice and spatial experience in the ‘liminoid’zones of English night-time cities. Urban Studies, 52, 571–588. doi: 10.1177/0042098013504005

- Rolando, S., Beccaria, F., Tigerstedt, C., & Törrönen, J. (2012). First drink: What does it mean? the alcohol socialization process in different drinking cultures. Drugs: Education, Prevention and Policy, 19, 201–212. doi: 10.3109/09687637.2012.658105

- Rolando, S., & Katainen, A. (2014). Images of alcoholism among adolescents in individualistic and collectivistic geographies. NAD Nordic Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 31, 189–205. doi: 10.2478/nsad-2014-0015

- Room, R. (1975). Normative perspectives on alcohol use and problems. Journal of Drug Issues, 5, 358–368. doi: 10.1177/002204267500500407

- Room, R. (1976). Ambivalence as a sociological explanation: The case of cultural explanations of alcohol problems. American Sociological Review, 41, 1047–1065

- Room, R. (1985). Foreword. In Bennett, L.A., & Ames, G.M. (Eds.), The American experience with alcohol: Contrasting cultural perspectives (pp. xi–xvii). New York and London: Plenum

- Room, R. (2005). Multicultural contexts and alcohol and drug use as symbolic behaviour. Addiction Research and Theory, 13, 321–331. doi: 10.1080/16066350500136326

- Room, R. (2010). Dry and wet cultures in the age of globalization. Salute e Società, 10(Suppl. 3), 229–237

- Room, R., & Mäkelä, K. (2000). Typologies of the cultural position of drinking. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 61, 475–483. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.15288/jsa.2000.61.475

- Room, R., & Mitchell, A. (1972). Notes on cross-national and cross-cultural studies. Drinking and Drug Practices Surveyor, 5, 16–20

- Sargent, M.J. (1968). Heavy drinking and its relation to alcoholism – with special reference to Australia. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Sociology, 4, 146–157. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/144078336800400206

- Shoveller, J., Viehbeck, S., Di Ruggiero, E., Greyson, D., Thomson, K., & Knight, R. (2015). A critical examination of representations of context within research on population health interventions. Critical Public Health. [Epub ahead of print]. DOI: 10.1080/09581596.2015.1117577

- Stickley, A., Jukkala, T., & Norstrom, T. (2011). Alcohol and suicide in Russia, 1870-1894 and 1956-2005: Evidence for the continuation of a harmful drinking culture across time? Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 72, 341–347. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.15288/jsad.2011.72.341

- Stivers, R. (1976). A hair of the dog: Irish drinking and American stereotype. University Park, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State University Press

- Straw, W. (1991). Systems of articulation, logics of change: Communities and scenes in popular music. Cultural Studies, 5, 368–388. doi: 10.1080/09502389100490311

- Sulkunen, P. (1976). Drinking patterns and the level of alcohol consumption: An international overview. In Gibbins, R., Israel, Y., Kalant, H., Popham, R.E., Schmidt, W., & Smart, R.G. (Eds.), Research advances in alcohol and drug problems (Vol. 3). New York: Wiley

- Sulkunen, P. (1983). Alcohol consumption and the transformation of living conditions. In Smart, R.G., Glaser, F.B., Israel, Y., Kalant, H., Popham, R.E., & Schmidt, W. (Ed.), Research advances in alcohol and drug problems (Vol. 7, pp. 247–298). New York: Plenum Press

- Taras, V., Rowney, J., & Steel, P. (2009). Half a century of measuring culture: Review of approaches, challenges, and limitations based on the analysis of 121 instruments for quantifying culture. Journal of International Management, 15, 357–373. doi: 10.1016/j.intman.2008.08.005

- Thornton, S. (1995). Club cultures: Music, media and subcultural capital. Cambridge: Polity Press

- Ullman, A.D. (1958). Sociocultural backgrounds of alcoholism. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 315, 48–54. doi: 10.1177/000271625831500107

- Unruh, D.R. (1980). The nature of social worlds. Pacific Sociological Review, 23, 271–296. doi: 10.2307/1388823

- Valentine, G., Holloway, S., Knell, C., & Jayne, M. (2008). Drinking places: Young people and cultures of alcohol consumption in rural environments. Journal of Rural Studies, 24, 28–40

- Victorian Government. (2008). Victoria’s Alcohol Action Plan 2008–2013: Restoring the balance. Melbourne: Victorian Government

- White, A., Castle, I.J.P., Chen, C.M., Shirley, M., Roach, D., & Hingson, R. (2015). Converging patterns of alcohol use and related outcomes among females and males in the United States, 2002 to 2012. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 39, 1712–1726. doi: 10.1177/002204267500500407

- Winlow, S., & Hall, S. (2006). Violent night: Urban leisure and contemporary culture. Oxford: Berg

- Yinger, M. (1960). Contraculture and subculture. American Sociological Review, 25, 625–635