Abstract

When stressed, people typically show elevated rates of displacement behaviour – activities such as scratching and face touching that seem irrelevant to the ongoing situation. Growing evidence indicates that displacement behaviour may play a role in regulating stress levels, and thus may represent an important component of the coping response. Recently, we found evidence that this stress-regulating effect of displacement behaviour is found in men but not in women. This sex difference may result from women's higher levels of public self-consciousness, which could inhibit expression of displacement behaviour due to the fear of projecting an inappropriate image. Here, we explored the link between public self-consciousness, displacement behaviour and stress among 62 healthy women (mean age = 26.59 years; SD = 3.61). We first assessed participants' public self-consciousness, and then quantified displacement behaviour, heart rate and cognitive performance during a Trier Social Stress Test (TSST) and used self-report questionnaires to assess the experience of stress afterwards. Public self-consciousness was negatively correlated with rate of displacement behaviour, and positively correlated with both the subjective experience of stress post-TSST and the number of mistakes in the cognitive task. Moderation analyses revealed that for women high in public self-consciousness, high levels of displacement behaviour were associated with higher reported levels of stress and poorer cognitive performance. For women low in public self-consciousness, stress levels and cognitive performance were unrelated to displacement behaviour. Our findings indicate that public self-consciousness is associated with both the expression of displacement behaviour and how such behaviour mediates responses to social stress.

Introduction

Displacement behaviour refers to a group of activities, such as scratching, face touching and lip biting, that seem irrelevant to the context in which they occur (Troisi, Citation1999). A number of studies have provided evidence that displacement behaviour is related to negative affective states, with such behaviour increasing in frequency when people feel anxious or stressed (Troisi, Citation2002). More recently, evidence has been provided that the expression of displacement behaviour may play an important role in the regulation of stress levels. Pico-Alfonso et al. (Citation2007) found that women who showed higher frequencies of displacement behaviour during a stressful mock interview subsequently showed a lower heart rate during the post-stressor recovery period. In a study of men, Mohiyeddini and Semple (2013) quantified displacement behaviour during a Trier Social Stress Test (TSST), a procedure designed to increase social stress (Kirschbaum et al., Citation1993), and found evidence that displacement behaviour during the test attenuated the relationship between the anxiety experienced immediately before the test started and the self-reported experience of stress afterwards.

The occurrence of displacement behaviour, and its role in regulating stress levels, may however differ markedly between the sexes. During a TSST, women engaged in displacement behaviour only about half as often as men, and subsequently reported higher levels of stress than did men (Mohiyeddini et al. unpublished). In men but not in women, higher rates of displacement behaviour were associated with lower self-reported stress levels; in addition, higher displacement behaviour rates were associated with poorer performance in a cognitive task in women, but not in men. Sex did not appear, however, to moderate the relationship between displacement behaviour and the physiological stress response: overall, higher rates of displacement behaviour were associated with lower measures of heart rate. The reasons for the differences found between men and women in the occurrence and apparent stress-regulating role of displacement behaviour are unclear, but may be linked to sex differences in levels of public self-consciousness (Mohiyeddini et al. unpublished).

Public self-consciousness denotes an individual's awareness of himself or herself as a social ‘object’ (Fenigstein et al., Citation1975). It reflects the tendency to think about aspects of the self, such as mannerisms or habitual and stylistic behaviour, that are subject to public scrutiny and from which impressions are formed (Carver & Scheier, Citation1981; Diener & Wallbom, Citation1976). It is now well established that women are more keenly aware than are men of their public self, and of the image they project (Rankin et al., Citation2004; Workman & Lee, Citation2011). Furthermore, women appreciate from an early age the importance of conveying a positive image of themselves, and as a result are more attentive to the social signals they send out, their expressive skills and the overall impression they provide to others (Bolino & Turnley, Citation2003; Lippa, Citation1976; Lee et al., Citation1999). Displacement behaviours, such as face touching, scratching and running fingers through hair, have the potential to act as social signals, and others may use these behaviours to make judgements about the person exhibiting them (Ekman & Friesen, Citation1969; Ingram, Citation1960). Consequently, there is good reason to expect that women might suppress displacement behaviours due to their high public self-consciousness, consequently disrupting the role of this behaviour in regulating stress levels.

In this study, we explored the relationship between public self-consciousness, displacement behaviour and stress among women, and also investigated how participants' levels of displacement behaviour affected others' perception of them. We first assessed levels of public self-consciousness among participants in our study, and then used a TSST to induce social stress. We assessed the self-reported experience of stress after the TSST, quantified a physiological measure of the stress response (change in heart rate) before, during and after this stressor, and also assessed performance in a cognitive task which formed part of the test. Finally, observers scored how nervous they perceived participants to be during the TSST. We hypothesized, first, that public self-consciousness would be negatively correlated with rates of displacement behaviour during the TSST, and positively correlated with the subsequent self-reported experience of stress, the physiological response and the number of mistakes in the cognitive task. Second, following the results of our earlier study (Mohiyeddini et al. unpublished), we hypothesized that rates of displacement behaviour would be unrelated to the experience of stress, negatively correlated with the physiological response to stress and positively correlated with mistakes in the cognitive task performance; in addition, based on the potential for observers to cue in to displacement behaviour, we predicted that rates of displacement behaviour would be positively correlated with observers' rating of nervousness of participants. Third, we examined a moderation model to test hypotheses that public self-consciousness alters the strength of the relationship between displacement behaviour and the self-reported experience of stress, physiological response, number of mistakes in the cognitive task and observers' rating of participants' nervousness.

Methods

The project was approved at the Department of Psychology at the University of Salzburg (Austria). The study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki, and all participants provided a written informed consent prior to their inclusion in the study.

Power analysis

We conducted an a priori power analysis using the software G-Power (Faul et al., Citation2007) which indicated that n = 59 participants needed to be included in the study in order to detect a medium-high effect size of η2 = 0.4 for displacement behaviour with a power of 0.95 or greater and α = 0.05.

Participants

A total of 65 adult female participants were recruited through advertisements. Exclusion criteria were medical conditions such as heart disease, diabetes and hypertension, and current or previous diagnosis of any psychosomatic or psychiatric illness. Furthermore, individuals were excluded in case of any allergies, atopic diathesis, rheumatic diseases, recreational drug use, medication or poor sleep pattern. All exclusion criteria were checked via a self-report questionnaire.

Three participants had to be excluded from the study because of incomplete questionnaire data, technical issues during the recording of the heart rate or their taking of medication, so that analyses were based on data from 62 participants. The participants were between 20 and 37 years old (M = 26.59; SD = 3.61). Of the participants, 87.1% were native German speakers, 87.1% were students and 12.9% were employees. Our measures did not correlate with participants' age (Pearson correlations: for all analyses, n = 62, r < 0.20, p > 0.11). Also, there were no differences between native versus non-native speakers (t-tests: for all analyses t60 < 1.06, p > 0.33) or differences between students versus employees (t-tests: for all analyses t60 < 1.67, p > 0.10), so that age, native language and occupational status were ignored in the analyses.

Menstrual cycle

In their review on the effects of sex and hormonal status on the physiological response to acute psychosocial stress, Kajantie & Phillips (Citation2006) concluded that it is crucial to take the menstrual phase and oral contraceptive use of subjects into account in study design, in order to control the natural variation of neuroendocrinological processes in the menstrual cycle and the impact of oral contraceptives on physiological and emotional responses to stress. Female participants in our sample were all tested in the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle, with this being assessed from their self-report on occurrence of menstruation; none of the participants were using oral contraceptives.

Public self-consciousness

This was measured using the German version (Filipp & Freudenberg, Citation1989) of the public self-consciousness subscale of the self-consciousness scale (Fenigstein et al., Citation1975). This subscale comprises seven items (e.g. ‘I’m concerned about the way I present myself' or ‘I’m concerned about what other people think of me'). Participants responded to each statement on a scale of 0 (extremely uncharacteristic) to 4 (extremely characteristic). Previous studies have established the validity of this subscale with reliability ranging from 0.76 to 0.84 (Anderson et al., Citation1996; Bernstein et al., Citation1986; Britt, Citation1992). Cronbach's α in the present study was 0.71.

Experimental setting and stress paradigm

Participants were informed that their behaviour and heart rate would be recorded during a simulated job interview and a cognitive test, in order to represent a professional setting. We used the TSST (Kirschbaum et al., Citation1993) which involves a simulated job interview (5 min) and a subsequent mental arithmetic task (5 min) with the participant standing in front of two people (one male and one female). For the arithmetic task, the participants were asked to subtract an odd number (17) from a larger number (2043), and then to continue this process of subtraction. In order to render the challenge more stressful, the interviewer interrupted the participants in case of miscalculation and asked them to start from the initial number.

The total duration of the experiment was 40 min and included the following procedure: In phase 1 (adaptation phase; 10 min), the subject was comfortably seated on a chair and her heart rate was recorded in the presence of one experimenter. In phase 2 (baseline phase; 10 min), the baseline heart rate was recorded at rest before the experimenter provided the instruction for the TSST. Phase 3 (stress phase; 10 min) included the simulated job interview (5 min) and the mental arithmetic task (5 min) in the presence of two experimenters. During the TSST, the participant's heart rate was recorded and the participant was video-recorded with face and torso in full view. Finally, in phase 4 (recovery phase; 10 min), the recovery heart rate of participants was recorded in the presence of one experimenter.

Quantification of displacement behaviour

A revised version of the ethological coding system for interviews (ECSI) was used to assess displacement behaviour. The ECSI is an ethogram measuring nonverbal behaviour during interviews (Troisi, Citation1999). It allows the assessment of 37 behaviour patterns. For this study, we only used the displacement scale (). Trained observers scored the subject's recorded behaviour according to the patterns listed in the ECSI. Recordings were rated independently by two trained observers. The recording method was one-zero sampling, a form of time sampling (Martin and Bateson, Citation1986). The recordings were divided into 15-s sample intervals (identified to observers by an acoustic signal). For each interval, the observers recorded whether the behaviour pattern of interest had occurred or not. Observers underwent training sessions prior to the study to ensure anadequate level of inter-observer reliability (i.e. a κ coefficient of > 0.85).

Table 1. Ethogram of the displacement behaviours recorded in this study.

Self-reported experience of stress

Participants completed visual analogue scales (VASs) ranging from 0 to 10 (with 0 indicating no stress experienced at all) to report their experience of stress after the TSST. The VAS required that the respondents specified their level of agreement to a statement by indicating a position along a continuous line between the two endpoints. VAS items are more reliable and show higher content validity than discrete scales and thus a wider range of statistical methods can be applied to these measurements (Reips & Funke, Citation2008). Participants were asked to rate whether they experienced the TSST as relaxing/stressful, clear/confusing, controllable/uncontrollable, energizing/exhausting, interesting/boring, pleasant/unpleasant, comfortable/embarrassing, challenging/fearful and calming/frightening. Previous research has confirmed the reliability and the validity of the German version of the VAS (Gaab et al., Citation2005). The average inter-correlation of the VAS items was 0.60 (p < 0.001) and Cronbach's α was 0.92.

Physiological measure of stress (haemodynamic measure)

Portable heart rate monitor devices (Polar system, S810, Polar, Kempele, Finland; Wirtz et al., Citation2006) were used to continuously acquire heart rate data. The R-R interval was quantified as the mean of each 10-min recording period (adaptation, baseline, stress task and recovery). Using the trapezoid formula, the area under the total response curve, expressed as area under the measured time points and ground from baseline to peak response (area under the curve for heart rate with respect to the ground (AUCg)) was calculated (Pruessner et al., Citation2003). The computation of the area under the curve is a frequently used method in psychophysiological research to estimate changes over a specific time period. It captures information that is contained in repeated measurements over time, and increases the power of the testing. Although cuff-based measurement of blood pressure can provide relevant data on the physiological stress response, we decided not to measure this becuase in a pilot trial the five participants reported that they avoided hand movements in order not to affect the measurement of blood pressure.

Cognitive measure of stress (arithmetic task performance)

In addition to the standard protocol of the TSST (Kirschbaum et al., Citation1993), we recorded the number of mistakes made during the mental arithmetic task, as a cognitive indicator of stress.

Rating of the TSST panel members

At the end of each TSST session, each panel member was asked to provide an overall rating of participants' nervousness using a scale ranging from 1 (not at all nervous) to 6 (very nervous). Nervousness was indicated by participants appearing agitated, edgy, distressed or jumpy. The ratings of panel members were highly correlated (r62 = 0.894, p < 0.001), and therefore the average of their two scores was used.

Statistical analyses

All calculations were carried out using SPSS v.20 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Data are presented as mean ± SD. In case of missing data, cases were excluded listwise. Data were tested for normal distribution using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test before statistical procedures were applied. Results were considered statistically significant at the p < 0.05 level.

Bivariate correlations

The associations between public self-consciousness, displacement behaviour, self-reported experience of stress, physiological and cognitive measures of stress and the observers' rating of participants' nervousness were explored using Pearson's correlations (two tailed).

Moderation analysis

To explore interaction effects between displacement behaviour and public self-consciousness, multiple regression analyses were carried out. Although there were no signs of multicollinearity (the variance inflation factor values were well below 2.5 and tolerance statistics well above 0.2), all variables were standardized in order to equate different metrics used in measuring variables (Dunlap & Kemery, Citation1987). The interaction term was created as a product term (public self-consciousness X displacement behaviour). Computing a hierarchical multiple regression, public self-consciousness and displacement behaviour were entered first in the equation, followed by the interaction term public self-consciousness X displacement behaviour. A moderator effect was indicated by a significant effect of the product term, while the effects of public self-consciousness and displacement behaviour were controlled. Significant moderation was evaluated by performing a test of simple slope analysis (Aiken & West, Citation1991).

Results

Public self-consciousness scores at the start of the study were 2.3 ± 0.57 (mean ± SD). During the 10-min TSST, subjects showed displacement behaviours in 22.2 ± 9.05 of the forty 15-s time blocks; scratch was the most frequent displacement behaviour (occurring in 5.3 ± 2.86 blocks), followed by hand-mouth (3.1 ± 2.08), groom (2.9 ± 1.31), fumble (2.9 ± 1.60), hand-face (2.9 ± 1.70), bite lips (1.7 ± 1.37), lick lips (1.7 ± 0.96), twist mouth (1.6 ± 0.88) and yawn (0.05 ± 0.22). After the TSST, subjects scored their experience of stress on the VAS as 4.70 ± 1.01. On average, participants made 7.0 ± 3.31 mistakes in the cognitive task. The average rating of participants' nervousness was 2.6 ± 1.43. The average heart rate in phase 1 (adaptation phase; 10 min) was 86.9 ± 12.11 beats per minute (bpm), in phase 2 (baseline phase; 10 min) 86.7 ± 11.41 bpm, in phase 3 (stress phase; 10 min) 110.9 ± 11.31 bpm and in phase 4 (recovery phase 10 min) 88.5 ± 11.31 bpm.

Bivariate correlations

displays the results of the bivariate correlation analyses. Public self-consciousness was negatively correlated with displacement behaviour (r62 = − 0.3 68, p = 0.003) and positively correlated with both the experience of stress (r62 = 0.390, p = 0.002) and the number of mistakes in the cognitive task (r62 = 0.356, p = 0.005). In contrast, public self-consciousness was not associated with the physiological response (r62 = 0.167, p = 0.20) or with the rating of participants' nervousness (r62 = − 0.161, p = 0.21).

Table 2. Bivariate correlations of public self-consciousness, displacement behaviour, measures of stress and ratings of participants' nervousness.

Displacement behaviour was negatively associated with the physiological response to stress (r62 = −0.276, p = 0.030) and positively associated with the rating of participants' nervousness (r62 = 0.387, p = 0.002). Displacement behaviour was not associated with the experience of stress (r62 = 0.168, p = 0.19) or with the number of mistakes in the cognitive task (r62 = 0.017, p = 0.89).

Moderation analysis

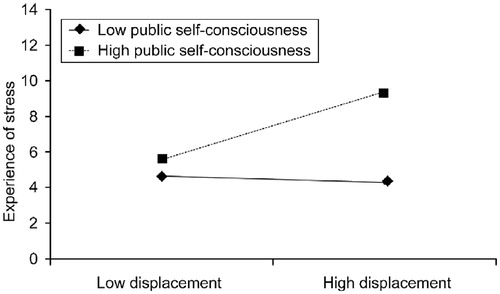

The results revealed a significant public self-consciousness X displacement behaviour effect (β = 1.934, t58 = 3.423, p = 0.001) on the self-reported experience of stress ( and ). After controlling for the first-order effects, the interaction between public self-consciousness and displacement behaviour was consistent with 12.4% of incremental variance in the experience of stress. Test of simple slopes revealed that the experience of stress varied with displacement behaviour for women high in public self-consciousness (b = 1.813, t58 = 4.643, p < 0.001): women with high levels of public self-consciousness (i.e. rates higher than the mean + 1 SD) reported higher levels of stress when they showed high rates of displacement behaviour. By contrast, the link between displacement behaviour and self-reported stress did not vary for women with low levels of public self-consciousness (i.e. rates lower than the mean −1 SD; b = −0.151, t58 = 0.471, p = 0.64).

Figure 1. Experience of stress during the TSST as a function of displacement behaviour and public self-consciousness. Low displacement behaviour/public self-consciousness was defined as below the mean − 1 SD; high was defined as above the mean + 1 SD. This figure displays the variation of experience of stress within the range of displacement behaviour and public self-consciousness using the test of simple slopes. The t-test results in conjunction with Bonferroni correction using median-split displacement behaviour and public self-consciousness revealed that the women high in both displacement behaviour and public self-consciousness (n = 15) reported significantly higher levels of stress than women low in displacement behaviour and high in public self-consciousness (n = 22); t(35) = 4.53, p < 0.001. Furthermore, women high in both displacement behaviour and public self-consciousness (n = 15) reported higher levels of stress than women high in displacement behaviour and low in public self-consciousness (n = 16); t(29) = 9.02, p < 0.001.

Table 3. Testing standardized moderator effects of public self-consciousness using a hierarchical multiple regression (n = 62).

The impact of the public self-consciousness X displacement behaviour interaction on the area under the curve for heart rate was not significant (β = 0.446, t58 = 0.646, p = 0.52; ). However, the association between displacement behaviour and the area under the curve was marginally nonsignificant (β = −0.248, t58 = 1.847, p = 0.07). Post hoc comparisons using Student's t-test revealed that women high in displacement behaviour showed a significantly lower heart rate (84.3 ± 10.98 bpm) in the post-stress phase compared with women low in displacement behaviour (92.8 ± 10.12 bpm; t60 = 3.175, p = 0.002).

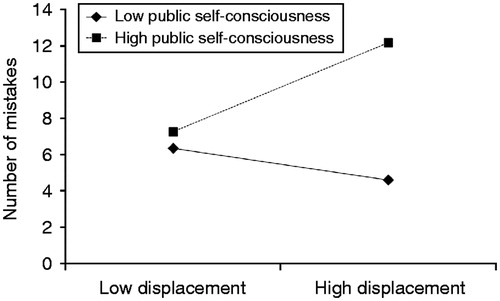

Furthermore, the public self-consciousness X displacement behaviour interaction effect on the number of mistakes in the cognitive task was significant (β = 1.881, t58 = 3.044, p = 0.004; and ). After controlling for the first-order effects, the interaction between public self-consciousness and displacement behaviour was consistent with 11.7% of incremental variance in the number of mistakes in cognitive task. Test of simple slopes revealed that the number of mistakes in the cognitive task varied with displacement behaviour for women high in public self-consciousness (b = 2.340, t58 = 3.331, p = 0.002): women with high levels of public self-consciousness made significantly more mistakes when they showed higher rates of displacement behaviour than women with lower levels of displacement behaviour. By contrast, the association between displacement behaviour and the number of mistakes did not vary among women with low levels of public self-consciousness (b = −0.802, t58 = −1.388, p = 0.17).

Figure 2. Number of mistakes in mental arithmetic task during the TSST as a function of displacement behaviour and public self-consciousness. Low displacement behaviour/public self-consciousness was defined as below the mean − 1 SD; high was defined as above the mean + 1 SD. This figure displays the variation in the number of mistakes in the cognitive task within the range of displacement behaviour and public self-consciousness, using the test of simple slopes. The t-test results in conjunction with Bonferroni correction using median-split displacement behaviour and public self-consciousness revealed that the women high in both displacement behaviour and public self-consciousness (n = 15) made significantly more mistakes in the cognitive task than women low in displacement behaviour and high in public self-consciousness (n = 22); t(35) = 3.12, p < 0.01. Furthermore, women high in both displacement behaviour and public self-consciousness (n = 15) made significantly more mistakes than women high in displacement behaviour and low in public self-consciousness (n = 16); t(29) = 6.82, p < 0.001. In addition, women low in displacement behaviour and low in public self-consciousness (n = 9) made significantly more mistakes in the cognitive task than women high in displacement behaviour and low in public self-consciousness (n = 16); t(23) = 5.85, p < 0.001.

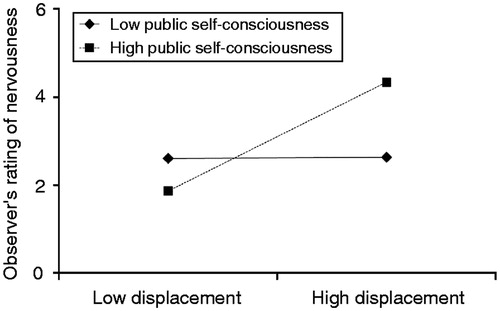

Furthermore, the public self-consciousness X displacement behaviour interaction effect on the observer's rating of nervousness of participants during TSST was significant (β = 1.599, t58 = 2.528, p = 0.014; and ). After controlling for the first-order effects, the interaction between public self-consciousness and displacement behaviour was consistent with 8.4% of incremental variance in the observers' rating. Test of simple slopes revealed that the observers' rating of nervousness of participants while performing the TSST varied with displacement behaviour for women high in public self-consciousness (b = 1.175, t58 = 3.378, p < 0.001): observers perceived more nervousness when women with high levels of public self-consciousness showed high rates of displacement behaviour. By contrast, the link between displacement behaviour and the rating of observers did not vary among women with low levels of public self-consciousness (b = 0.019, t58 = 0.076, p = 0.94).

Figure 3. Observer's rating of nervousness of participants during the TSST as a function of displacement behaviour and public self-consciousness. Low displacement behaviour/public self-consciousness was defined as below the mean − 1 SD; high was defined as above the mean + 1 SD. This figure displays the variation in observers' rating of nervousness within the range of displacement behaviour and public self-consciousness, using the test of simple slopes. The t-test results in conjunction with Bonferroni correction using median-split displacement behaviour and public self-consciousness revealed that women high in both displacement behaviour and public self-consciousness (n = 15) were rated as more nervous than women low in displacement behaviour and high in public self-consciousness (n = 22); t(35) = 3.50, p < 0.01.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to explore the relationship between public self-consciousness, displacement behaviour and stress levels. In line with our expectations, bivariate correlations revealed that women with higher public self-consciousness showed lower rates of displacement behaviours during a TSST, reported higher stress levels afterwards and more mistakes in the cognitive task that formed part of this procedure. Displacement behaviour was uncorrelated with the reported experience of stress or with the number of mistakes in the cognitive task, but was negatively related to a measure of heart rate, indicating a role for displacement behaviour in regulating the physiological stress response. Participants showing higher rates of displacement behaviour were judged to be more nervous, indicating that observers can use displacement behaviour to infer information about emotional state. Finally, moderation analyses provided evidence that for women with high levels of public self-consciousness (but not for those with low public self-consciousness), high rates of displacement behaviour were associated with a greater experience of stress, more mistakes in the cognitive task and being perceived as more nervous. Overall, these findings provide new insights into the interactions between public self-consciousness, displacement behaviour and stress levels among women.

The negative association between public self-consciousness and rates of displacement behaviour in our study indicates that women who are more self-conscious suppress displacement behaviour as they feel it to be socially inappropriate and/or because they are concerned with how such behaviour may be perceived. In the light of consistent findings that women show higher levels of public self-consciousness than men (Rankin et al., Citation2004), this link between public self-consciousness and displacement behaviour may help us to understand recent evidence that displacement behaviour is associated with reduced stress levels among men but not women (Mohiyeddini et al. unpublished): if displacement behaviour has an important role to play in regulating the stress response and the experience of stress, then active suppression of such behaviour for fear of how it may be perceived may disrupt this aspect of the coping response. Moreover, our results have important implications for the field of clinical psychiatry, in which quantification of displacement behaviour during clinical interviews has been proposed to provide a useful index of negative affective state (Shreve et al., Citation1988) and has been used to explore key aspects of psychiatric disorders such as schizophrenia (Troisi et al., Citation1998; Troisi, Citation1999). The strong association between public self-consciousness and rates of displacement behaviour in our study indicates that this aspect of personality may be crucial to consider in any context where assessment of displacement behaviour is utilized in a clinical setting.

Public self-consciousness was also positively related to the self-reported experience of stress and number of mistakes in the cognitive task, but it is important to note that these two measures were themselves highly correlated and that stress levels and cognitive performance during the TSST may have fed back on each other. In this study, the experimenter pointed out mistakes in the cognitive task to the participant when they occurred. Individuals that have high public self-consciousness may experience this as being particularly stressful, due to a fear that mistakes might result in giving a less favourable impression; their emotional reactions may further impede their performance, in turn triggering additional stress responses and further mistakes. Overall, however, these results add to evidence that high levels of public self-consciousness can in a non-responsive social setting (the observers in our study were instructed not to show any emotional or verbal responses to the participants) lead to an increased experience of stress (Else-Quest et al., Citation2012) and impaired cognitive performance (Reeves et al., Citation1995).

Our finding that the rate of displacement behaviour among women is unrelated to the self-reported experience of stress replicates our previous findings from a female study population (Mohiyeddini et al. unpublished) and contrasts markedly with data from men, in which higher rates of displacement are associated with significantly lower levels of self-reported stress (Mohiyeddini and Semple, in press; Mohiyeddini et al. unpublished). However, in line with a previous study of women (Pico-Alfonso et al., Citation2007), we found that the frequency of displacement behaviours was negatively related to our measure of heart rate. As a coping behaviour, displacement behaviour among women thus seems to be effective at the physiological level, but not at the level of the subjective feeling of stress. For men, by contrast, such behaviour seems to be effective at both levels (Mohiyeddini and Semple, in press; Mohiyeddini et al. unpublished). Women's concern, conscious or subconscious, about how others perceive displacement behaviour may be a key factor underlying this sex difference. The finding that observers rated participants who displayed displacement behaviours more frequently as being more nervous indicates that people can indeed use observed displacement behaviour as a cue to an individual's inner emotional states.

The results of the moderation analyses revealed that women who scored high in both public self-consciousness and displacement behaviour reported higher levels of stress, made more mistakes in the cognitive task and were perceived as more nervous, when compared with women that scored high in public self-consciousness but low in displacement behaviour. No such variation with frequency of displacement behaviour was observed in women with low public self-consciousness scores. These results indicate that women with high levels of public self-consciousness are particularly detrimentally affected when they also display high rates of displacement behaviour, potentially because they are more acutely aware of how such behaviour may be interpreted (Carver & Scheier, Citation1981; Rankin et al., Citation2004; Workman & Lee, Citation2011). One might expect such concern about public impression to lead to suppression of displacement behaviour, and indeed in bivariate analyses these measures were negatively related. Concealing emotion-related behaviour can have negative emotional and cognitive consequences, however (Gross, Citation2002; Srivastava et al., Citation2009), and it may be that only a certain degree of suppression of displacement behaviour can be achieved, after which point its occurrence is particularly stressful and disruptive to cognitive performance for highly public self-conscious individuals. Furthermore, public self-consciousness may limit the use of displacement behaviour, due to the sociocultural interpretation of such behaviour in social situations. For instance, behaviours such as scratching, licking of the lips or raising the hand to the mouth contradict the socio-culturally determined western understanding of appropriateness (Bussey & Bandura, Citation1999; Bandura & Bussey, Citation2004; Moore, Citation1985) and politeness (Kemper, Citation1984) of female social behaviour and ‘ladylike’ manners (Carter & Patterson, Citation1982; Maslow, Citation1937) and such behaviour may also be perceived as flirtatious (Moore, Citation1985). The question of whether suppression of displacement behaviour by individuals high in public self-consciousness results from a mainly conscious and intentional process, or rather results from a primarily subconscious one, needs further empirical investigation.

With respect to the potential signalling value of displacement behaviour, it is of interest that in the moderation analysis, there was evidence that rates of displacement behaviour strongly affected judgement of nervousness for women high in public self-consciousness, but had no such effect for women with low public self-consciousness. Observers appear, therefore, to be integrating information provided by displacement behaviour with information contained in other signals; an elevation in displacement may not be sufficient in itself to convey nervousness and other signs known to be associated with public self-consciousness, such as blushing (Bogels et al., Citation1996; Edelmann, Citation1990), may be required for observers to infer emotional state.

The difference in this study between physiological and emotional changes related to the display of displacement behaviour merits further investigation. However, such a difference is not necessarily unexpected. The discrepancy hypothesis, based on the idea proposed by Lazarus (Citation1966), maintains that the pattern of stress coping responses on the behavioural-expressive, physiological-biochemical and subjective-affective levels could be interpreted as indicators for the employment of psychological coping mechanisms and hence ‘... we should not necessarily expect all classes of response to agree with each other. It is their combined pattern that yields the best information about the psychological processes we wish to understand’ (p. 387). Accordingly, the difference between the changes in physiological and emotional measures related to the frequency of occurrence of displacement behaviour could be an indicator of the effectiveness of ongoing psychological coping mechanisms.

Strengths of this study include the structured experimental setting and procedures, high internal validity and the inclusion of multiple measures of stress. However, we acknowledge that the external validity of the findings may be limited, and it is important therefore for future research to explore the issues investigated here in a more naturalistic setting. Furthermore, repeating the present research with male participants would provide more conclusive insights into the issue of whether sex differences in public self-consciousness may explain the differences observed between men and women in the frequency of displacement behaviours and in the stress-regulating function of these behaviours (Mohiyeddini and Semple unpublished). What the current study does make clear is that public self-consciousness is an important factor that should be taken into consideration in studies that quantify displacement behaviour, explore its role in regulating stress or use such behaviour as a tool in clinical psychiatry.

Declaration of interest

We thank the University of Salzburg for financial support. Dr Julia Lehmann provided invaluable feedback on an earlier version of this manuscript. The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

References

- Aiken LS, West SG. (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage

- Anderson EM, Bohon LM, Berrigan LP. 1996. Factor structure of the private self-consciousness scale. J Personal Assess 66: 144–52

- Bandura A, Bussey K. (2004). On broadening the cognitive, motivational, and sociostructural scope of theorizing about gender development and functioning: Comment on Martin, Ruble, and Szkrybalo (2002). Psychol Bull 130:691–701

- Bernstein IH, Teng G, Garbin CP. (1986). A confirmatory factoring of the self-consciousness scale. Multi Be Re 21:459–75

- Bogels SM, Alberts M, de Jong PJ. (1996). Self-consciousness, self-focused attention, blushing propensity and fear of blushing. Personal Indiv Diff 21:573–81

- Bolino MC, Turnley WH. (2003). More than one way to make an impression: Exploring profiles of impression management. J Manag 29:141–60

- Britt TW. (1992). The self-consciousness scale: On the stability of the three-factor structure. Personal Soc Psychol Bull 18:748–55

- Bussey K, Bandura A. (1999). Social cognitive theory of gender development and differentiation. Psychol Rev 106:676–713

- Carter DB, Patterson CJ. (1982). Sex roles as social conventions: The development of children's conceptions of sex-role stereotypes. Dev Psychol 18:812–24

- Carver CS, Scheier MF. (1981). Self-consciousness and reactance. J Res Personal 15:16–29

- Diener E, Wallbom M. (1976). Effects of self-awareness on antinormative behaviour. J Res Personal 10:107–11

- Dunlap WP, Kemery ER. (1987). Failure to detect moderating effects: Is multicollinearity the problem? Psychol Bull 102:418–20

- Edelmann RJ. (1990). Chronic blushing, self-consciousness, and social anxiety. J Psychopathol Behav Assess 12:119–27

- Else-Quest NM, Higgins A, Allison C, Morton LC. (2012). Gender differences in self-conscious emotional experience: a meta-analysis. Psych Bull 138:947–81

- Ekman P, Friesen WV. (1969). The repertoire of nonverbal behaviour: Categories, origins, usage and coding. Semiotica 1:49–98

- Faul F, Erdfelder E, Lang A-G, Buchner A. (2007). G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav Res Methods 39:175–91

- Fenigstein A, Scheier MF, Buss AH. (1975). Public and private self-consciousness: Assessment and theory. J Consult Clin Psychol 43:522–7

- Filipp SH, Freudenberg E. (1989). Der Fragebogen zur Erfassung dispositioneller Selbstaufmerksamkeit (SAM-Fragebogen). Gottingen: Hogrefe

- Gaab J, Rohleder N, Nater UM, Ehlert U. (2005). Psychological determinants of the cortisol stress response: The role of anticipatory cognitive appraisal. Psychoneuroendocrinology 30:599–610

- Gross J. (2002). Emotion regulation: Affective, cognitive, and social consequences. Psychophysiology 39:281–91

- Ingram GIC. (1960). Displacement activity in human behavior. Am Anthropol 62:994–1003

- Kajantie E, Phillips DI. (2006). The effects of sex and hormonal status on the physiological response to acute psychosocial stress. Psychoneuroendocrinology 31:151–78

- Kemper S. (1984). When to speak like a lady. Sex Roles 10:435–43

- Kirschbaum C, Pirke K-M, Hellhammer DH. (1993). The ‘Trier Social Stress Test': A tool for investigating psychobiological stress responses in a laboratory setting. Neuropsychobiology 28:76–81

- Lazarus RS. (1966). Psychological stress and the coping process. New York: McGraw-Hill

- Lee S-J, Quigley BM, Nesler MS, Corbett AB, Tedeschi JT. (1999). Development of a self-presentation tactics scale. Personal Indiv Diff 26:701–22

- Lippa R. (1976). Expressive control and the leakage of dispositional introversion-extraversion during role-played teaching. J Personal 44:541–59

- Martin P, Bateson P. (1986). Measuring behaviour: An introductory guide. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

- Maslow AH. (1937). Dominance-feeling, behaviour, and status. Psychol Rev 44:404–29

- Mohiyeddini C, Semple S. 2013. Displacement behaviour regulates the experience of stress in men. Stress 16:163–71

- Moore MM. (1985). Nonverbal courtship patterns in women: Context and consequences. Ethol Sociobiol 6:237–47

- Pico-Alfonso MA, Mastorci F, Ceresini G, Ceda GP, Manghi M, Pino O, Troisi A, Sgoifo A. (2007). Acute psychosocial challenge and cardiac autonomic response in women: The role of estrogens, corticosteroids, and behavioural coping styles. Psychoneuroendocrinology 32:451–63

- Pruessner JC, Kirschbaum C, Meinlschmid G, Hellhammer DH. (2003). Two formulas for computation of the area under the curve represent measures of total hormone concentration versus time-dependent change. Psychoneuroendocrinology 28:916–31

- Rankin JL, Lane DJ, Gibbons FX, Gerrard M. (2004). Adolescent self-consciousness: Longitudinal age changes and gender differences in two cohorts. J Res Adolesc 14:1–21

- Reeves AL, Watson PJ, Ramsey A, Morris RJ. (1995). Private self-consciousness factors, need for cognition, and depression. J Sol Be Personal 10:431–43

- Reips U-D, Funke F. (2008). Interval-level measurement with visual analogue scales in Internet-based research: VAS generator. Behav Res Methods 40:699–704

- Shreve EG, Harrigan JA, Kues JR, Kagas DK. (1988). Nonverbal: Expressions of anxiety in physician-patient interactions. Psychiatry 51:378–84

- Srivastava S, Tamir M, McGonigal KM, John OP, Gross JJ. (2009). The social costs of emotional suppression: A prospective study of the transition to college. J Pers Soc Psychol 96:883–97

- Troisi A. (1999). Etiological research in clinical psychiatry: The study of nonverbal behaviour during interviews. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 23:905–13

- Troisi A. (2002). Displacement activities as a behavioural measure of stress in nonhuman primates and human subjects. Stress 5:47–54

- Troisi A, Spalletta G, Pasini A. (1998). Non-verbal behaviour deficits in schizophrenia: An ethological study of drug-free patients. Acta Psychiatr Scand 97:109–15

- Wirtz PH, von Kanel R, Mohiyeddini C, Emini L, Ruedisueli K, Groessbauer S, Ehlert U. (2006). Low social support and poor emotional regulation are associated with increased stress hormone reactivity to mental stress in systemic hypertension. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 91:3857–65

- Workman JE, Lee SH. (2011). Vanity and public self consciousness: A comparison of fashion consumer groups and gender. Int J Consum Stud 35:307–15