Abstract

Previous research on the association between maternal daily stress and cortisol in pregnancy has yielded inconsistent findings. However, past studies have not considered whether stressful experiences in childhood impact maternal cortisol regulation in pregnancy. In this pilot study, we aimed to examine whether the association between maternal daily stress and cortisol differed according to maternal history of child abuse. Forty-one women provided salivary cortisol samples at wake-up, 30 min after wake-up, and bedtime for 3 days at three times over second and third trimesters of pregnancy. On each day of cortisol collection women reported their daily stress. Women reported child abuse experiences prior to age 18 years by completing 15 items from the Adverse Childhood Experiences Scale. Twenty-one percent (N = 9) of women reported a history of child sexual abuse (CSA), 44% (N = 18) reported a history of non-sexual child abuse and 34% (N = 14) reported no history of child abuse. Hierarchical Linear Modeling (HLM) analyses revealed that stress in the day prior was associated with increases in morning cortisol in women with CSA histories compared to women with non-sexual abuse histories or no history of child abuse. Increases in evening cortisol were associated with increases in daily stress in women with CSA histories compared to women with non-sexual abuse histories or no history of child abuse. Results reveal a dynamic association between daily stress and cortisol in pregnancy and suggest that patterns differ according to maternal child abuse history.

Introduction

Maternal hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) functioning is hypothesized to act as a key mechanism linking maternal stress in pregnancy to adverse neonatal outcomes (Rich-Edwards & Grizzard, Citation2005; Wadhwa et al., Citation2011). However, studies on the association between stress and HPA activity in pregnancy have yielded inconsistent findings (Davis et al., Citation2007; Goedhart et al., Citation2010; Harville et al., Citation2009; Obel et al., Citation2005). Inconsistencies may be due, in part, because previous research has failed to consider whether stressful experiences in childhood influence maternal HPA activity in pregnancy. This gap in the knowledge base is significant given the robust literature showing that stressful early life experiences have profound and permanent effects on HPA regulation (Miller et al., Citation2010).

In this study, we assessed whether associations between maternal daily stress and diurnal cortisol varied according to maternal child abuse history. Specifically, childhood sexual abuse (CSA) has been associated with both hyper- and hypo-activity of the HPA axis in non-pregnant samples (Bremner et al., Citation2003; Cicchetti et al., Citation2010; De Bellis et al., Citation1994; Lemieux & Coe, Citation1995). Recent work by our group indicated that cortisol trajectories over pregnancy differ according to maternal history of CSA (Bublitz & Stroud, Citation2012): women with CSA histories displayed increasing cortisol awakening responses over gestation compared to women with non-sexual abuse histories or no abuse history.

As a next step, we sought to understand whether associations between maternal daily stress and cortisol varied as a function of child abuse history. We examined whether the associations among stress and cortisol on the same day, and stress and cortisol across days, differed according to maternal child abuse history. We examined day-to-day associations between stress and cortisol because past research in non-pregnant samples shows a dynamic association between daily experiences and cortisol, such that cortisol patterns are modified both by same-day and prior-day challenge (Adam et al., Citation2006; Doane & Adam, Citation2010).

Methods

Participants

Women in this pilot study were pregnant women who participated in a larger study on the effects of maternal mood on fetal and infant development [Behavior and Mood in Mothers, Behavior in Infants (BAMBI) Study]. Women were excluded from participating if they had medical conditions or were taking medications that could affect cortisol, reported more than one alcoholic drink per week over pregnancy, were over 40 years old, were pregnant with more than one fetus or were at increased risk for adverse neonatal outcomes.

Forty-one pregnant women participated in the pilot study (Mage = 26, SD = 5). Women were from diverse economic (45% of sample reported a total household income of <$30 K/year; 69% with less than a college degree) and racial (63% Caucasian) backgrounds. Fifty-four percent of pregnancies were reported as unplanned and 55% of women reported that they were unmarried at the time of this pregnancy. This study was approved by the Women and Infants Hospital IRB.

Procedure

Women completed three study sessions at 20 (SD = 2), 28 (SD = 1) and 35 (SD = 1) weeks gestation. At baseline, women completed a self-report measure of child abuse experiences, provided information on demographics, medical conditions, medications, health behaviors, mood and information on past pregnancies. For 3 days, after each of the three study sessions, women completed a measure of daily stress and provided saliva cortisol samples (passive drool) at wake-up, 30 min after waking and bedtime for a total of 9 days of stress/cortisol collection per participant. Time of samples was verified via Medication Event Monitoring System (MEMS) caps (AARDEX, Zurich, Switzerland) for 67% of the sample.

Child abuse history

Women were asked to report on child abuse experiences by completing 15 items from the Adverse Childhood Experiences Scale (Dube et al., Citation2003). This measure asked whether participants had experienced childhood sexual abuse, physical abuse, witnessed domestic violence or experienced physical neglect prior to age 18 years. Response options ranged from 0 = never to 4 = very often. Women who reported scores of 1 or higher were considered to have experienced abuse. Women were categorized as “No Child Abuse (NA)” if they had never experienced any of the items in the measure, “Non-sexual Child Abuse (CA)” if they endorsed one or more adverse experiences other than sexual abuse, and “Child Sexual Abuse (CSA)” if they endorsed having experienced child sexual abuse with or without other adverse childhood experiences.

Maternal salivary cortisol

Saliva samples were frozen at −80°C and shipped to Dresden University for analysis. Cortisol concentrations were analyzed in duplicate with an immunoassay with time-resolved fluorescence detection. Intra- and inter-assay coefficients of variation were <8%. For women with both self-reported and MEMS-recorded saliva sampling times there was an average time discrepancy of 5 min (SD = 5) for cortisol samples at awakening, 5 min (SD = 4) for cortisol samples collected 30 min after awakening and 7 min (SD = 29) for cortisol samples collected at bedtime. These discrepancies suggest that the majority of participants were collecting cortisol samples at the self-reported sampling times. Sampling time was included as a covariate in HLM analyses.

Daily stress

On each evening following salivary cortisol collection, women reported the severity of daily stressors by completing a modified version of the Pregnancy Experiences Scale (DiPietro et al., Citation2008). Women were asked, “How stressful were the following things for you today?” and were provided with a list of 13 stressors, including difficulties with their romantic partner, family, friends, financial and work stressors, thoughts about the health/well-being of the baby and pregnancy discomforts (i.e. sleep problems, pain). Responses ranged from 0 = not at all to 3 = very. Responses were summed on each day to create a daily stress variable.

Maternal demographic characteristics

Women provided information on demographics (age, race, marital status, income) and past births (gravida). Participants reported their pre-pregnancy height and weight to compute body mass index (BMI). Participants also provided information on mood (Inventory for Depressive Symptomatology) (Rush et al., Citation1986) and anxiety (Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale) (Hamilton, Citation1959). At all study sessions, alcohol and cigarette consumption were measured using Timeline Follow-Back interview (Sobell et al., Citation1996). Participants in this study were not included in our previous study on maternal child abuse history and cortisol awakening responses over gestation (Bublitz & Stroud, Citation2012).

Data analysis

Salivary cortisol values were log transformed to adjust for skewed distributions. In order to accurately capture the cortisol awakening response, morning saliva samples that were collected <20 or >40 min apart were removed from analyses. This resulted in missing values for 10% of cortisol samples at awakening (355 samples out of a possible 369 for analysis of stress and cortisol on the same day; 237 samples out of a possible 246 samples for analysis of stress and cortisol the next day) and 10% of samples collected 30 min after awakening (352 samples out of a possible 369 for analysis of stress and cortisol on the same day; 236 samples out of a possible 246 samples for analysis of stress and cortisol the next day). As well, 9% of evening cortisol samples were missing due to non-completion or non-compliance (348 samples out of a possible 369 for analysis of stress and cortisol on the same day; 236 samples out of 246 possible samples for analysis of stress and cortisol the next day).

To determine whether associations between daily stress and cortisol were moderated by maternal child abuse group, we computed two-level hierarchical linear models (HLM) using Hierarchical Linear Modeling software (Raudenbush & Bryk, Citation2002). At level 1, we examined the within-person associations among daily stress and cortisol. At level 2, we examined whether associations among daily stress and cortisol were moderated by maternal child abuse group (and significant covariates). Models were computed separately for cortisol values at awakening, 30 min following awakening and bedtime. Time of sampling and gestational age at sampling were included as covariates in all models.

We computed three models to examine same-day associations between stress and cortisol (trajectories over awakening, 30 min after awakening and evening) and three models to examine associations between prior-day stress and cortisol (trajectories over awakening, 30 min after awakening and evening). In models in which we examined same-day associations between cortisol and stress, stress was considered the dependent variable given that women reported their daily stress after providing saliva samples. In models in which we examined associations between prior-day stress and cortisol, cortisol was modeled as the dependent variable because samples were collected after the experience of stress. This analytic approach has been employed in prior studies (Adam, Citation2006; Doane & Adam, Citation2010). Analyses of same-day associations between stress and cortisol included all 9 days of data collection over pregnancy. Analyses of associations among daily stress and next-day cortisol included 6 days of data over pregnancy as we did not have cortisol data on the day after the last day of women reported on daily stress.

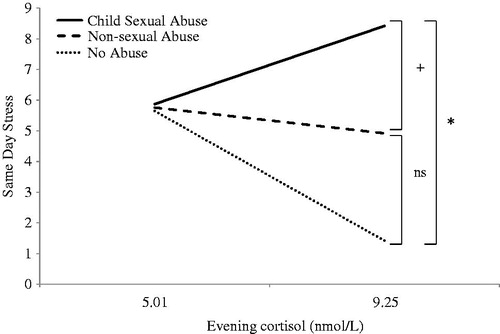

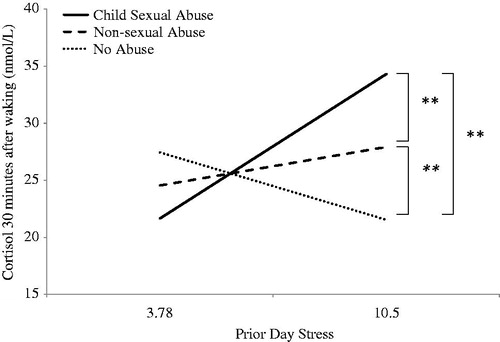

We performed post hoc HLM models to test whether the relationship between daily stress and cortisol differed between pairs of child abuse groups (i.e. CSA vs no abuse). In and , we used HLM software to model the predicted patterns of associations between daily stress and cortisol among women with CSA histories, non-sexual or no abuse histories. Daily stress and cortisol were assessed as continuous variables; however, HLM models associations among stress and cortisol at the 25th and 75th percentiles to model the within-person predicted patterns of associations. While log transformed cortisol values were included in analyses, raw values are presented in the figures. Figures contain brackets to indicate significant differences in paired comparisons of maternal child abuse groups.

Figure 1. Associations between evening cortisol and same-day stress by maternal child abuse group. Brackets indicate results from post hoc paired group comparisons of child abuse groups. Hierarchical linear models controlled for time of sampling, gestational age at assessment, maternal income and gravida. +p < 0.10; *p < 0.05; ns = not significant.

Figure 2. Associations between prior-day stress and cortisol 30 min after waking by maternal child abuse group. Brackets indicate results from post hoc paired group comparisons of child abuse groups. Hierarchical linear models controlled for time of sampling, gestational age at assessment, maternal income and gravida. **p < 0.01.

Results

Descriptive statistics

Twenty-one percent (N = 9) of women reported a history of child sexual abuse (CSA), 44% (N = 18) reported a history of non-sexual child abuse and 34% (N = 14) reported no history of child abuse. One-way analyses of variance (ANOVA) and chi-squared tests were performed using SPSS software for Windows (version 19) to assess whether child abuse groups differed on maternal characteristics. Child abuse groups significantly differed only on gravida (F(2,18) = 4.22, p = 0.03). Tukey’s post hoc comparisons showed that women with a history of CSA reported a greater number of past pregnancies than NA women (p = 0.01) and non-CSA women reported a marginally greater number of past pregnancies than NA women (p = 0.10). Gravida was included as a covariate in analyses. No other differences were found among child abuse groups.

We also examined associations between maternal characteristics, cortisol and stress using hierarchical linear models. Results showed that maternal income significantly predicted cortisol at awakening (b = 0.70, SE = 0.30, p = 0.03), but not 30 min after waking (b = 0.69, SE=0.53, p = 0.20) or bedtime (b = −0.14, SE = 0.19, p = 0.48). As income increased, maternal cortisol at awakening also increased. Maternal income was included as a covariate in all models. No other significant associations were found between maternal characteristics and cortisol levels at awakening (p values > 0.14), cortisol levels 30 min after awakening (p values > 0.13) or bedtime cortisol levels (p values > 0.16).

Analyses of associations between maternal characteristics and daily stress revealed that, as gravida increased, maternal daily stress increased (b = 1.70, SE = 0.60, p = 0.01). As previously noted, gravida was included as a covariate in all models. In addition, as symptoms of depression increased daily stress increased (b = 0.43, SE = 0.14, p = 0.005). However, because depressive symptoms did not predict cortisol, depressive symptoms were not included as a covariate in subsequent models. No other significant associations were found between daily stress and maternal characteristics (p values > 0.12).

All women delivered babies that were full-term (M = 39.69 weeks gestation; range: 38.13–41.86). No babies were born low birth weight (M = 3336 g; range: 2605–4610). APGAR scores, a measure of the physical condition of a newborn infant rated on a scale from 0–10 with higher scores indicating better health, reflected that babies in this sample were in good health when babies were scored 5 min following delivery (M = 9; range: 7–10). Neonatal outcomes did not significantly differ according to maternal child abuse group (p values > 0.15).

Associations between daily stress and diurnal cortisol by child abuse group

All results are presented in . Results from HLM analyses examining maternal abuse as a moderator of the association between daily stress and same-day cortisol revealed that abuse history significantly moderated associations between evening cortisol levels and stress reported the same evening (b = 0.14, SE = 0.07, p = 0.04) (). Post hoc paired-group comparisons revealed that, as evening cortisol levels increased, self-reported stress levels were higher in women with child sexual abuse histories versus women with no abuse history (b = 0.13, SE = 0.06, p = 0.05). As well, as evening cortisol levels increased, stress levels were marginally higher in women with child sexual abuse histories versus non-sexual abuse histories levels (b = 0.24, SE = 0.13, p = 0.07). Finally, as evening cortisol levels increased there were no significant differences in daily stress levels in women with non-sexual abuse histories versus women with no abuse history (b = 0.01, SE = 0.05, p = 0.75). Maternal child abuse history did not significantly moderate associations among morning cortisol levels and stress reported the same evening (p values > 0.45).

Table 1. Maternal history of child abuse as a moderator of associations between daily stress and cortisol.

Next we examined whether maternal history of child abuse moderated the associations among prior-day stress and cortisol. Results revealed that maternal history of child abuse significantly moderated the association between prior-day stress and cortisol at 30-min post-awakening (b = 0.79, SE = 0.33, p = 0.02) (see ). Post hoc analyses of group differences revealed that as prior-day stress increased, cortisol at 30 min after awakening increased in women with CSA histories versus women with no history of child abuse (b = 0.69, SE = 0.32, p = 0.01). Cortisol levels at 30 min after awakening increased as prior-day stress increased in women with non-sexual child abuse histories versus women with no abuse (b = 3.67, SE = 0.99, p = 0.001). Finally, post hoc analyses revealed that as prior-day stress increased, cortisol levels 30 min after awakening increased in women with sexual abuse histories compared to women with child non-sexual abuse histories (b = −2.67, SE = 0.78, p = 0.002). Maternal history of child abuse did not significantly moderate the association between daily stress and next-day cortisol at awakening or at bedtime (p values > 0.30).

Discussion

The aim of this pilot study was to assess whether the associations between daily stress and cortisol in pregnancy varied according to maternal history of child abuse. We found that increases in evening cortisol were associated with increases in daily stress in women with CSA histories compared to women with non-sexual abuse histories or no history of child abuse. As well, we found that prior-day stress was associated with increases in morning cortisol in women with CSA histories compared to women with non-sexual abuse histories or no history of child abuse. These results are consistent with those from past studies in non-pregnant samples showing that prior-day feelings of loneliness and sadness were associated with altered diurnal cortisol rhythms, including greater morning cortisol output and flatter cortisol slopes (Adam et al., Citation2006; Doane & Adam, Citation2010). According to the “boost” hypothesis proposed by Adam et al. (Citation2006), an increase in morning cortisol following adverse prior-day experiences may provide the individual with extra energy and resources to help manage future daily challenges. As an alternative explanation, Adam et al. (Citation2006) also suggested that higher morning cortisol levels could reflect a (maladaptive) prolonged stress response that carried over from the previous day. Future research is needed to examine potential consequences of these altered cortisol patterns on maternal and neonatal health.

Previous studies have shown that, over typically developing pregnancies, morning cortisol levels decline as pregnancy progresses (Buss et al., Citation2009; Entringer et al., Citation2010). Thus, cortisol patterns observed in this study may be indicative of maternal HPA dysregulation. Results also indicate that women with CSA histories may display greater HPA dysregulation following stress compared to women with histories of child abuse that was non-sexual in nature. Prior findings on the impact of child maltreatment type on cortisol regulation are mixed (Bremner et al., Citation2003; Cicchetti et al., Citation2010; De Bellis et al., Citation1994; Lemieux & Coe, Citation1995). However, in pregnancy, prior work by our group found that women with CSA histories displayed more dysregulated diurnal cortisol patterns compared to women with non-sexual child abuse histories and no abuse history (Bublitz & Stroud, Citation2012). As well, past research has found that women with CSA histories are at greater risk for pregnancy complications compared to women with other forms of abuse (Leeners et al., Citation2010; Noll et al., Citation2007). Thus, maternal cortisol dysregulation following stress may serve as a biological pathway linking CSA history to adverse neonatal outcomes, though future studies are needed to examine this hypothesis.

This pilot study was the first, to our knowledge, to examine whether the association between maternal daily stress and cortisol in pregnancy differed according to maternal history of child abuse. Results are preliminary and limited by the small sample size and retrospective recall of maternal history of child abuse. As well, we included a small number of daily saliva samples in order to minimize participant burden; however this may limit the accuracy of our measure of diurnal cortisol rhythms. Despite these limitations, findings shed light on the dynamic association between daily experiences and diurnal cortisol in pregnancy, and the importance of considering associations both same-day and prior-day challenge when examining maternal cortisol output over pregnancy.

Declaration of interest

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare. Funding for this study was provided by NIH grant R01MH079153 to L.R.S. M.H.B.’s time was supported by T32HL076134-07.

References

- Adam EK. (2006). Transactions among adolescent trait and state emotion and diurnal and momentary cortisol activity in naturalistic settings. Psychoneuroendocrinology 31(5):664–79

- Adam EK, Hawkley LC, Kudielka BM, Cacioppo JT. (2006). Day-to-day dynamics of experience – cortisol associations in a population-based sample of older adults. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103(45):17058–63

- Bremner JD, Vythilingam M, Anderson G, Vermetten E, McGlashan T, Heninger G, Rasmusson A, et al. (2003). Assessment of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis over a 24-hour diurnal period and in response to neuroendocrine challenges in women with and without childhood sexual abuse and posttraumatic stress disorder. Biol Psychiatry 54:710–18

- Bublitz MH, Stroud LR. (2012). Childhood sexual abuse predicts diurnal cortisol in pregnancy: preliminary findings. Psychoneuroendocrinology 37(9):1425--30

- Buss C, Entringer S, Reyes JF, Chicz-DeMet A, Sandman CA, Waffarn F, Wadhwa PD. (2009). The maternal cortisol awakening response in human pregnancy is associated with the length of gestation. Am J Obstet Gynecol 201(4):398 e1–8

- Cicchetti D, Rogosch FA, Gunnar MR, Toth SL. (2010). The differential impacts of early physical and sexual abuse and internalizing problems on daytime cortisol rhythm in school-aged children. Child Dev 81(1):252–69

- Davis EP, Glynn L, Dunkel-Schetter C, Hobel C, Chicz-Demet A, Sandman CA. (2007). Prenatal exposure to maternal depression and cortisol influences infant temperament. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 46(6):737–46

- De Bellis MD, Chrousos GP, Dorn LD, Burke L, Helmers K, Kling MA, Trickett PK, et al. (1994). Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis dysregulation in sexually abused girls. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 78:249–55

- DiPietro JA, Christensen AL, Costigan KA. (2008). The Pregnancy Experiences Scale – brief version. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol 29(4):262–7

- Doane LD, Adam EK. (2010). Loneliness and cortisol: momentary, day-to-day, and trait associations. Psychoneuroendocrinology 35(3):430–41

- Dube SR, Felitti VJ, Dong M, Chapman DP, Giles WH, Anda RF. (2003). Childhood abuse, neglect, and household dysfunction and the risk of illicit drug use: the adverse childhood experiences study. Pediatrics 111(3):564–72

- Entringer S, Buss C, Shirtcliff EA, Cammack AL, Yim IS, Chicz-DeMet A, Sandman CA, et al. (2010). Attenuation of maternal psychophysiological stress responses and the maternal cortisol awakening response over the course of human pregnancy. Stress 13(3):258–68

- Goedhart G, Vrijkotte TG, Roseboom TJ, van der Wal MF, Cuijpers P, Bonsel GJ. (2010). Maternal cortisol and offspring birthweight: results from a large prospective cohort study. Psychoneuroendocrinology 35(5):644–52

- Hamilton M. (1959). The assessment of anxiety states by rating. Br J Med Psychol 32(1):50–5

- Harville EW, Savitz DA, Dole N, Herring AH, Thorp JM. (2009). Stress questionnaires and stress biomarkers during pregnancy. J Women’s Health 18(9):1425–33

- Leeners B, Stiller R, Block E, Görres G, Rath W. (2010). Pregnancy complications in women with childhood sexual abuse experiences. J Psychosom Res 69:503–10

- Lemieux AM, Coe CL. (1995). Abuse-related posttraumatic stress disorder: evidence for chronic neuroendocrine activation in women. Psychosom Med 57:105–15

- Miller GE, Chen E. (2010). Harsh family climate in early life presages the emergence of a proinflammatory phenotype in adolescence. Psychol Sci 21(6):848–56

- Noll J, Schulkin J, Trickett PK, Susman EJ, Breech L, Putnam FW. (2007). Differential pathways to preterm delivery for sexually abused and comparison women. J Pediatr Psychol 32(10):1238–48

- Obel C, Hedegaard M, Henriksen TB, Secher NJ, Olsen J, Levine S. (2005). Stress and salivary cortisol during pregnancy. Psychoneuroendocrinology 30:647–56

- Raudenbush SW, Bryk AS, editors. (2002). Hierarchical linear models: applications and data analysis methods. 2 edn. Newbury Park: SAGE. 485 p

- Rich-Edwards JW, Grizzard TA. (2005). Psychosocial stress and neuroendocrine mechanisms in preterm delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol 192(5 Suppl.):S30–5

- Rush AJ, Giles DE, Schlesser MA, Fulton CL, Weissenburger J, Burns C. (1986). The Inventory for Depressive Symptomatology (IDS): preliminary findings. Psychiatry Res 18(1):65–87

- Sobell IC, Brown J, Leo GI, Sobell MB. (1996). The reliability of the Alcohol Timeline Followback when administered by telephone and by computer. Drug Alcohol Depend 42:49–54

- Wadhwa PD, Entringer S, Buss C, Lu MC. (2011). The contribution of maternal stress to preterm birth: issues and considerations. Clin Perinatol 38:351–84