abstract

Accumulations of health and social problems challenge current health systems. It is hypothesized that professionals should renew their expertise by adapting generalist, coaching, and population health orientation capacities to address these challenges. This study aimed to develop and validate an instrument for evaluating this renewal of professional expertise. The (Dutch) Integrated Care Expertise Questionnaire (ICE-Q) was developed and piloted. Psychometric analysis evaluated item, criterion, construct, and content validity. Theory and an iterative process of expert consultation constructed the ICE-Q, which was sent to 616 professionals, of whom 294 participated in the pilot (47.7%). Factor analysis (FA) identified six areas of expertise: holistic attitude towards patients (Cronbach’s alpha [CA] = 0.61) and considering their social context (CA = 0.77), both related to generalism; coaching to support patient empowerment (CA = 0.66); preventive action (CA = 0.48); valuing local health knowledge (CA = 0.81); and valuing local facility knowledge (CA = 0.67) point at population health orientation. Inter-scale correlations ranged between 0.01 and 0.34. Item-response theory (IRT) indicated some items were less informative. The resulting 26-item questionnaire is a first tool for measuring integrated care expertise. The study process led to a developed understanding of the concept. Further research is warranted to improve the questionnaire.

Introduction

Most health- and social-care professionals are specialists trained to combat the acute, single diseases of the past, but not necessarily today’s multiple and chronic ones (Jones, Podolsky, & Greene, Citation2012). Populations increasingly suffer from multimorbidity, especially in the context of deprivation, which frequently involves the accumulation of medical and social conditions. Evidence indicates that people with multiple chronic conditions already represent 50% of the burden of disease (Anderson, Citation2011; Barnett et al., Citation2012). As a consequence, patients must consult a broad range of specialists, at least one for each problem. This is arguably the root of the unsustainable functioning of healthcare systems (Plochg, Klazinga, Schoenstein, & Starfield, Citation2011; Plochg, Klazinga, & Starfield, Citation2009).

Emerging evidence indicates that having multiple, complex social and/or health problems is associated with poor outcomes in terms of quality of life (Fortin, Soubhi, Hudon, Bayliss, & van den Akker, Citation2007), longer hospital stays (Wright et al., Citation2003), more avoidable admissions and complications (Wolff, Starfield, & Anderson, Citation2002), higher mortality (Gijsen et al., Citation2001), increased service use (Salisbury, Johnson, Purdy, Valderas, & Montgomery, Citation2011; Wolff et al., Citation2002), and higher costs (Friedman, Jiang, Elixhauser, & Segal, Citation2006; Nagl, Witte, Hodek, & Greiner, Citation2012).

It is increasingly acknowledged that a renewal of professional expertise is warranted to fit the changing burden of disease (Plochg et al., Citation2009). Professionals who are equipped to address the contemporary health needs can provide effective and efficient services (e.g. Barnett et al., Citation2012; Jurgutis, Vainiomäki, Puts, & Jukneviciute, Citation2012; Tinetti, Fried, & Boyd, Citation2012). Renewed expertise draws on three major, though separate, debates in the literature. First generalism, a response to (sub)specialization, and consequently fragmentation in care for multimorbid patients (e.g. Barnett et al., Citation2012; Jurgutis et al., Citation2012; Luijks et al., Citation2012; Starfield, Citation2011; Tinetti et al., Citation2012). Second, coaching in order to empower patients to self-manage their care, in which professionals are increasingly present due to the chronic nature of diseases (Hibbard, Greene, & Tusler, Citation2009; Thompson, Citation2007). In this view, a responsive professional is favoured over paternalism (Loignon & Boudreault-Fournier, Citation2012). Third, population health orientation and prevention (Novick, Morrow, & Mays, Citation2008), which combats immature population health services (Lundy, Citation2010; Yach, Hawkes, Gould, & Hofman, Citation2004). Future health- and social-care professionals should develop integrated care expertise in these three areas (Box 1).

To develop the concept and start building its empirical evidence base, measurement tools are imperative. The objective of this article is to describe the first attempt at developing and validating an instrument for measuring integrated care expertise among health- and social-care professionals.

Methods

The Integrated Care Expertise Questionnaire (ICE-Q) was constructed and validated in four phases ().

Figure 1. Flow chart of the study process.

Phase I: Construction of the questionnaire

The aim of this phase was to select and/or construct items that cover integrated care expertise. The literature was explored for the three areas of expertise, i.e. generalism, coaching, and population health orientation. We performed searches for each in the MEDLINE (PubMed) and Google Scholar databases by using controlled vocabulary and text words, covering (equivalents of) the terms “questionnaire” and “capacities.” New items were drafted if none were available in existing questionnaires. In this process we used qualitative data gathered in focus groups and semi-structured interviews (professional, patient, policy, and insurer perspectives), within the context of a participatory action research project in deprived neighbourhoods in the cities of Utrecht and Amsterdam (The Netherlands). Poor health outcomes had driven their city councils and insurers to support collaboration between health- and social-care professionals. These collaborations were the reason to study integrated care expertise thoroughly beforehand.

Phase II: Expert consultation

In the second phase, the items were presented to experts of the research project (researchers and policymakers, n = 16). The aim was to examine whether experts confirmed the three areas of integrated care expertise, whether items covered them well (content validity), whether items were relevant, and whether items were well understood (face validity). If necessary, new items were constructed jointly. Each of the experts was consulted separately, mainly in writing. Additionally, three meetings were organized.

Phase III: Field consultation

In the third phase, the questionnaire was tested among potential participants (health and social care). The aim of this phase was to test whether the questionnaire tapped into professionals’ perception of their environment, and whether they understood the questionnaire (face validity). Information was collected by organizing face-to-face sessions (n = 8) during which the questionnaire was filled out and thoughts were shared about what crossed the participant’s mind while doing so.

Phase IV: Pilot and statistical analysis

An invitation to fill out the resulting ICE-Q digitally (LimeSurvey) was sent to medical- and social-care professionals (n = 616) in the selected deprived neighbourhoods in February 2012 for a pilot. The invitees included all professions that deliver extramural care. Professionals received a reminder after approximately 4, 8, and 12 weeks. Ethical approval was not required under Dutch law, since no patients were involved. Questionnaire data were stored anonymously.

In addition, the questionnaire included items for collecting contextual (possibly confounding) information, such as individual characteristics of participants, their work environment, and motives. Opportunities for making comments (on content and/or questionnaire) were provided. These items were also used for validation and interpretation purposes.

Validation of the psychometric properties of the ICE-Q (plan based on (Terwee et al., Citation2007)) consisted of four steps (: Phase IV, a–d), explained hereafter. IBM SPSS version 19 was used for statistical analyses.

Item validity

Item validity was analysed by assessing item’s discriminatory power (distribution), and redundancy between items. Items with ≥95% of the responses in one category (low discriminatory power) were removed. Redundancy was assessed by interpreting the inter-item correlation using Cronbach’s alpha (CA). Items were considered to possibly be redundant if |CA| ≥ 0.9. In addition, qualitative information in the open text fields (comments) was assessed, and professionals and policymakers (n = 8) reflected on and discussed interpretation(s) of items.

Internal consistency and FA

Internal consistency was assessed by calculating CAs for each area of expertise. CA does not measure unidimensionality, but is appropriate to conform whether a set of items is actually unidimensional (Cortina, Citation1993). Two exploratory Factor Analyses (FAs) were used to study the areas of expertise in-depth, maximizing the resulting constructs by an iterative interpretation process.

At this point, the ICE-Q was determined and its psychometric properties retrieved. Item-total correlations (internal consistency) were calculated, and considered satisfactory for the possible identification of a sub-scale if CA ≥ 0.60. Two researchers interpreted the results independently. Corrected item-total correlations were used to assess homogeneity of scales; items were deleted when not fitting any construct. The inter-scale correlations between factors were used to check whether the constructs were distinct from each other. A value of 0.70 or less was considered satisfactory for supporting the construct structure.

Construct validity

Validity of ICE-Q constructs was addressed by testing theories. Variables found to influence expertise were profession, alliance context, and experience. Different professions were expected to have different ICE-Q scores, because balance in the biopsychosocial paradigm as well as demands varies by profession (Hall, Citation2008). For instance, GPs are more generalistic, due to the broader scope of their profession. The literature does not provide clues however either on the other areas of expertise, or on how other professions fit in this theory. Regarding alliances, working in a team is expected to produce higher scores for generalism as well (Ferrer, Hambidge, & Maly, Citation2005). Finally, we hypothesized that professionals with less experience are more likely to adopt integrated care expertise, because they know more about multimorbidity and are inclined to change (Southern, Bellin, & Arnsten, Citation2011).

To test whether ICE-Q construct scores (continuous) detected the influence of profession (categorical variable) on integrated care expertise one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) analyses were conducted, in addition to Tukey’s post hoc test when significant differences were identified between professions. To test whether ICE-Q construct scores could detect the dependency of the alliance context (dichotomous) on integrated care expertise, we conducted unpaired t-tests. For the ability of the ICE-Q to test the association between integrated care expertise and years of experience (continuous), Pearson correlation coefficients were calculated for each sub-scale.

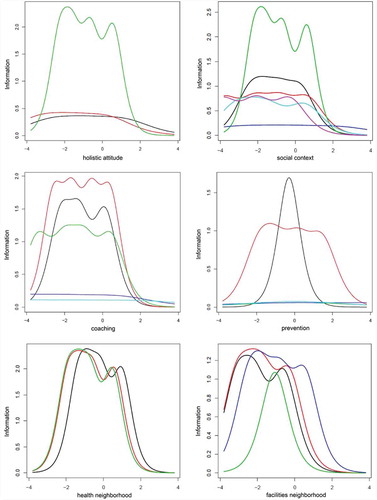

Item-response theory (informativeness)

Within an item-response theory (IRT) framework (Van de Linden, & Hambleton, Citation1996), graded response models were used to obtain item information curves: a visualization of the informativeness of items within each construct (one-dimensional latent variables) – that is, the ability of each item to discriminate respondents who vary on its latent trait.

Results

Phase I: Construction of the questionnaire

None of the questionnaires found in the literature could be used literally. However, several questionnaires were used as references when drafting items: two for “generalism” (Akhtar-Danesh et al., Citation2010; Bonomi, Wagner, Glasgow, & VonKorff, Citation2002), one for “coaching” (Bonomi et al., Citation2002), and two for “population health orientation” (Akhtar-Danesh et al., Citation2010; Gauld, Bloomfield, Kiro, Lavis, & Ross, Citation2006).

Most of the items were case-based, and presented realistic situations concerning accumulations of social and health problems (familiar situations within the context of deprived neighbourhoods). Other items presented general questions about attitude and behaviour in day-to-day practice. All 31 items were constructed as 5-point Likert scales, since expertise was assumed to have a fixed position on the underlying latent continuum (Dijkstra, Citation1991). Higher scores reflect higher expertise for integrated care.

Phase II: Expert consultation

The experts considered all items as fitting the areas of expertise closely after minor revisions regarding familiarity of cases for all of the potential participants’ professions. A few additional items with regard to the concept of generalism were drafted, as experts suggested items may have been missed in the non-medical contextual factors. This resulted in a 42-item questionnaire.

Phase III: Field consultation

Consulted professionals indicated that several items were repetitive, and some stated that other items did not concern their day-to-day practice. In the latter category were items on diagnosing, which was beyond the responsibility of some professionals. These items were either deleted (if repetitive) or rephrased and retested. Professionals also stressed the difference between their attitude and behaviour towards colleagues within or outside their team. Sub-items were drafted for both situations. The third phase resulted in the first complete draft of the ICE-Q, with 34 items.

Phase IV: Pilot and statistical analysis

A total of 294 professionals started (47.7%), and 206 filled out all items of the questionnaire (33.4%). Health- and social-care organizations were involved and encouraged participation. The majority worked within a multidisciplinary alliance (65.3%) and is confronted regularly with complex cases (66.2%). Respondents represented various professions ().

Table 1. Respondent characteristics. Self-reported, except for profession (categorized by experts). Data represent the number of respondents in each category (n) and the percentage (in parentheses), except for “experience” (mean (± standard deviation)).

Item validity

Neither of the items showed insufficient discriminatory power (maximum 91.1% in a single category), nor were redundant (maximum inter-item correlation CA was 0.74). Analysis of open text comments in the questionnaire and the focus group with professionals and policymakers indicated that reliability of two items was possibly doubtful.

The first item concerned the legal objections to share patients’ information with colleagues, which many respondents mentioned as having influenced their response. The item therefore did not measure professionals’ expertise. Because legal aspects actually do apply to this situation, we chose to remove the item.

The second item concerned discussing topics with patients beyond their professional scope. Experts indicated that professionals would do so in principle, and answer accordingly, although they compromise on this professional duty in practice due to contextual factors (e.g., time). The responses did not go beyond social desirability however, which was also reflected in the low discriminatory power. The item was deleted.

Internal consistency and FA

The remaining 32 items showed high internal consistency (CA = 0.80). The initial areas of expertise were confirmed mostly. Internal consistency of coaching (five items, CA = 0.66) and population health orientation (eight items, CA = 0.78) were satisfactory. Only the construct of generalism (seven items, CA = 0.44) was not satisfactory at that point.

FA confirmed the initial areas of expertise and distinguished sub-aspects, as had been reckoned by the experts in Phase II. The first exploratory FA (principal components extraction, eigenvalue >1, no rotation) revealed 11 components, explaining 69% of the variance. Three researchers (MA, JB, and TP) interpreted the output independently. Six meaningful factors were identified and three items were excluded. The second FA (principal components extraction, varimax rotation) on the remaining variables was therefore restricted to maximum six factors. They explained 51% of the variance. Three variables loaded low, and were removed. The output of the other 26 variables is shown in , suppressing loadings ≤0.39. Two items (17 and 18) loaded sufficiently on both “prevention” and “valuing local health knowledge”. These results indicate interrelatedness of factors. These items were assigned based on the researchers’ interpretations and should possibly be considered later for removal.

Table 2. Results of the second FA.

Internal consistency of the six constructs ranged from 0.61 to 0.81, except prevention (CA = 0.48). Corrected item-total scale correlations were high, apart from four items (13, 14, 18, and 19). The last two items were part of the construct that itself showed low internal consistency. All inter-scale correlations ranged from 0.01 to 0.34 (), which considerably exceed the threshold. This indicates that each factor is a separate entity. The six meaningful constructs were interpreted and labelled (Box 2).

Table 3. Inter-scale correlations.

Construct validity

One-way ANOVA confirmed that the ICE-Q could detect influences of profession on each of the sub-scales: coaching, prevention, valuing knowledge on local facilities (all p < 0.001), social context (p = 0.004), holistic attitude (p = 0.072), and valuing local health knowledge (p = 0.083). Tukey’s post hoc tests indicated however that neither profession scored consistently higher.

ICE-Q scores could detect the positive effect of working in multidisciplinary teams on all sub-scales as well, although the differences were small and only significant for social context (t = 1.81, p = 0.072), prevention (t = 1.90, p = 0.059), and valuing local health knowledge (t = 1.80, p = 0.073).

The ICE-Q could not detect the theoretical positive influence of years of experience on integrated expertise, as correlation coefficients with all constructs were between −0.30 and 0.30, and mostly not significant.

Item-response theory (informativeness)

The item information curves () indicate that items within constructs are unequally informative, although most items are informative. The x-axis represents the possible scores of items on the latent trait scale; the y-axis shows the ability of each item to discriminate respondents with different scores on that latent trait. Especially holistic attitude and prevention turn out to have only few items with high informativeness. Still, internal consistency was sufficient. Adjustment of less-informative items could therefore improve constructs.

Discussion

This article aimed to describe the first attempt to develop and validate an instrument for measuring integrated care expertise in four phases. Initially, three areas of expertise were identified. During the validation process these were confirmed, and developed further. This resulted in a 26-item questionnaire (see Appendix), covering six (sub-)areas of expertise.

Given its novelty, the ICE-Q developmental process was inherently iterative, which was a limitation of the validations’ methodology. This raises concerns on the factor structure identified. Replication studies should be performed to show stability of the factors. On the other hand, the iterative process was helpful in understanding the concept. Furthermore, research needs to include non-deprived neighbourhoods too, because accumulation of health problems, which integrated care expertise responds to, is not restricted to deprived areas only. Variation in Dutch care practice and health outcomes is low, but other countries may need to take this into account.

Even so, a comparison to other measures (criterion validity) could not be made due to the lack of similar instruments. As this field is still in its infancy, hypotheses for assessing construct validity were scarce as well. It is simply unclear how areas of expertise compare to other measures, because none of them has been approached quantitatively before. An educated guess would be, for example, that higher ICE-Q scores correlate with a smaller number of professionals being involved in the care process of patients suffering from multimorbidity. Such hypothesis should be attended to in the future.

The case-based items were deemed to gather the targeted information better when they were tailored to everyday situations within the specific domains; however, a single version was preferred for validation purposes. The issue of domain versions should be studied in more detail when applying the ICE-Q in practice.

The initial conceptual overview has not been refuted, but rather elaborated upon, by refining integrated care expertise into six dimensions (), which we interpret as covering both the individual level (1–3) and the community level (4–6). The authors consider the resulting questionnaire to be a preliminary instrument that should be developed further, along with understandings of integrated care expertise, which equips professionals to better combat the current burden of disease.

Though six (sub-)areas of expertise were identified, their loadings indicated interrelatedness. This supports the WHO’s notion of good stewardship: expertise as an indivisible capacity. The authors therefore wish to assign a sum score to the overall latent variable of integrated care expertise, or good stewardship. However, there is no consensus on the importance (weight) of each area of expertise. We recommend using the sub-scales separately. Further research is needed to develop a sum score.

Concluding comments

The goal of this study was to develop and validate an instrument for measuring professionals’ integrated care expertise. As such this study paves the way for the (quantitative) assessment of professional expertise and additionally provides insights into its understanding. By starting to quantify sub-areas of expertise, researchers will be able to study the role of integrated care expertise. The authors therefore hope that other studies will take up the challenge to continue the efforts described in this article.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the social and healthcare professionals involved with the project. The authors would also like to thank Sabine Quak (Public Health Service of Utrecht) and Judith van de Mast (Achmea Health Insurance) for their help in preparing the data set on the categorization of professions, and Marie-Louise Essink-Bot for sharing her expertise to improve the validation process.

Declaration of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the writing and content of this article.

References

- Akhtar-Danesh, N., Valaitis, R. K., Schofield, R., Underwood, J., Martin-Misener, R., Baumann, A., & Kolotylo, C. (2010). A questionnaire for assessing community health nurses’ learning needs. Western Journal of Nursing Research, 32, 1055–1072.

- Anderson, G. (2011). For 50 years OECD countries have continually adapted to changing burdens of disease; the latest challenge is people with multiple chronic conditions. Paris, France: OECD Publishing.

- Arah, O. A. (2009). On the relationship between individual and population health. Medicine, Health Care and Philosophy, 12, 235–244.

- Barnett, K., Mercer, S. W., Norbury, M., Watt, G., Wyke, S., & Guthrie, B. (2012). Epidemiology of multimorbidity and implications for health care, research, and medical education: A cross-sectional study. The Lancet, 380, 37–43.

- Bonomi, A. E., Wagner, E. H., Glasgow, R. E., & VonKorff, M. (2002). Assessment of chronic illness care (ACIC): A practical tool to measure quality improvement. Health Services Research, 37, 791–820.

- Cortina, J. M. (1993). What is coefficient alpha? An examination of theory and applications. Journal of Applied Psychology, 78, 98.

- Dijkstra, L. (1991). The Likert attitude scale: Theory and practice. Eindhoven: Technische Universiteit Eindhoven.

- Ferrer, R. L., Hambidge, S. J., & Maly, R. C. (2005). The essential role of generalists in health care systems. Annals of Internal Medicine, 142, 691–699.

- Fortin, M., Soubhi, H., Hudon, C., Bayliss, E. A., & van den Akker, M. (2007). Multimorbidity’s many challenges. British Medical Journal, 334, 1016–1017.

- Friedman, B., Jiang, H. J., Elixhauser, A., & Segal, A. (2006). Hospital inpatient costs for adults with multiple chronic conditions. Medical Care Research and Review, 63, 327–346.

- Gauld, R., Bloomfield, A., Kiro, C., Lavis, J., & Ross, S. (2006). Conceptions and uses of public health ideas by New Zealand government policymakers: Report on a five-agency survey. Public Health, 120, 283–289.

- Getz, L., Kirkengen, A. L., & Ulvestad, E. (2011). The human biology-saturated with experience. Tidsskrift for den Norske Laegeforening, 131, 683–687.

- Gijsen, R., Hoeymans, N., Schellevis, F. G., Ruwaard, D., Satariano, W. A., & van den Bos, G. A. (2001). Causes and consequences of comorbidity: A review. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 54, 661–674.

- Hall, R. E. (2008). From generalist approach to evidence-based practice: The evolution of social work technology in the 21st century. Critical Social Work, 9. Retrieved from http://www1.uwindsor.ca/criticalsocialwork/from-generalist-approach-to-evidence-based-practice-the-evolution-of-social-work-technology-in-the-2

- Hibbard, J. H., Greene, J., & Tusler, M. (2009). Improving the outcomes of disease management by tailoring care to the patient’s level of activation. The American Journal of Managed Care, 15, 353–360.

- Jones, D. S., Podolsky, S. H., & Greene, J. A. (2012). The burden of disease and the changing task of medicine. New England Journal of Medicine, 366, 2333–2338.

- Jurgutis, A., Vainiomäki, P., Puts, J., & Jukneviciute, V. (2012). Strategy for continuous professional development of Primary Health Care professionals in order to better response to changing health needs of the society. ImPrim Report #5. Klaipeda, Lithuania: Klaipeda University. Retrieved from http://www.ku.lt/svmf/files/2012/10/Report_5-Strategy-for-Continuous-Professional-Development-of-Primary-Health-Care-professionals-in-order-to-better-respond-to-changing-health-needs-of-the-society.pdf

- Kindig, D., & Stoddart, G. (2003). What Is Population Health? American Journal of Public Health, 93, 380–383.

- Loignon, C., & Boudreault-Fournier, A. (2012). From paternalism to benevolent coaching: New model of care. Canadian Family Physician Medecin de famille canadien, 58, 1194–1195, e1618–1199.

- Luijks, H. D., Loeffen, M. J., Lagro-Janssen, A. L., van Weel, C., Lucassen, P. L., & Schermer, T. R. (2012). GPs’ considerations in multimorbidity management: A qualitative study. The British Journal of General Practice, 62, e503–510.

- Lundy, T. (2010). A paradigm to guide health promotion into the 21st century: The integral idea whose time has come. Global Health Promotion, 17, 44–53.

- Nagl, A., Witte, J., Hodek, J. M., & Greiner, W. (2012). Relationship between multimorbidity and direct healthcare costs in an advanced elderly population. Results of the PRISCUS trial. Zeitschrift für Gerontologie und Geriatrie, 45, 146–154.

- Novick, L. F., Morrow, C. B., & Mays, G. P. (2008). Public health administration: Principles for population-based management. Ontario: Jones & Bartlett Publishers.

- Plochg, T., Klazinga, N. S., Schoenstein, M., & Starfield, B. (2011). Reconfiguring health professions in times of multimorbidity: Eight recommendations for change. In OECD (Ed.), Health Reform: Meeting the Challenge of Ageing and Multiple Morbidities (pp. 109–141). Paris, France: OECD Publishing. doi:10.1787/9789264122314-7-en

- Plochg, T., Klazinga, N., & Starfield, B. (2009). Transforming medical professionalism to fit changing health needs. BMC Medicine, 7, 64.

- Royal College of General Practitioners. (2012). Medical generalism. Why expertise in whole person medicine matters. London, UK: College of General Practitioners.

- Salisbury, C., Johnson, L., Purdy, S., Valderas, J. M., & Montgomery, A. A. (2011). Epidemiology and impact of multimorbidity in primary care: A retrospective cohort study. The British Journal of General Practice, 61, e12–21.

- Southern, W. N., Bellin, E. Y., & Arnsten, J. H. (2011). Longer lengths of stay and higher risk of mortality among inpatients of physicians with more years in practice. The American Journal of Medicine, 124, 868–874.

- Starfield, B. (2011). Point: The changing nature of disease: Implications for health services. Medical Care, 49, 971–972.

- Terwee, C. B., Bot, S. D., de Boer, M. R., van der Windt, D. A., Knol, D. L., Dekker, J., … de Vet, H. C. (2007). Quality criteria were proposed for measurement properties of health status questionnaires. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 60, 34–42.

- Thompson, A. G. (2007). The meaning of patient involvement and participation in health care consultations: A taxonomy. Social Science and Medicine, 64, 1297–1310.

- Tinetti, M. E., Fried, T. R., & Boyd, C. M. (2012). Designing health care for the most common chronic condition—Multimorbidity. The Journal of the Americal Medical Association, 307, 2493–2494.

- Van de Linden, W. J., & Hambleton, R. K. (1996). Handbook of modern item response theory. New York, NY: Springer-Verlag.

- Wolff, J. L., Starfield, B., & Anderson, G. (2002). Prevalence, expenditures, and complications of multiple chronic conditions in the elderly. Archives of Internal Medicine, 162, 2269–2276.

- Wright, S., Verouhis, D., Gamble, G., Swedberg, K., Sharpe, N., & Doughty, R. (2003). Factors influencing the length of hospital stay of patients with heart failure. European Journal of Heart Failure, 5, 201–209.

- Yach, D., Hawkes, C., Gould, C. L., & Hofman, K. J. (2004). The global burden of chronic diseases: Overcoming impediments to prevention and control. The Journal of the American Medical Association, 291, 2616–2622.

Appendix

Table A1. Outline of the ICE-Q.