Abstract

The aim of the study was to assess the safety and efficacy of laparoscopic treatment of distal infiltrative ureteral endometriosis with segmental ureteral resection, ureteroneocystostomy, and vesicopsoas hitch. We performed a retrospective analysis of perioperative data and looked at follow-up outcomes of patients with deep endometriosis with ureteral involvement treated by laparoscopic vesicopsoas hitch. Six patients were treated for left ureteral endometriosis in the study period. Four of those were diagnosed during previous laparoscopies. A ureteroneocystostomy (Lich-Gregoir reimplantation procedure) with vesicopsoas hitch was fashioned laparoscopically in all cases, and a double-J stent was applied intraoperatively. There were no intraoperative or postoperative complications and no cases of extravasation of contrast at cystogram one week after surgery. The median follow-up time was 38 months (range 12–56). All patients had normal renal ultrasound or intravenous pyelogram results at one year follow-up. This study confirmed that laparoscopic ureteroneocystostomy and vesicopsoas hitch is a safe and effective option in the management of distal ureteral endometriosis. In view of the small size of this series, multicenter studies are needed to confirm these conclusions.

Introduction

Endometriosis, which is the presence of endometrial tissue outside the uterus, affects 5-10% of women of childbearing age (Citation1–3). Endometriosis can be classified as peritoneal, ovarian, or deep infiltrating endometriosis (DIE) (Citation4). DIE, characterized by the infiltration of anatomic structures within the pelvis, is defined as a lesion that infiltrates 5 mm or more into the peritoneum (Citation5–7). DIE typically involves the pouch of Douglas, the uterosacral ligaments, and the recto-vaginal septum; however, it can affect the urinary tract as well.

Urinary tract endometriosis (UTE) is characterized by the presence of endometrial glands and stroma in or around the urinary bladder wall, ureters, urethra, and kidney (Citation8). It is estimated to affect between 0.3% and 6% of patients with a diagnosis of endometriosis (Citation9). The ratio of bladder/ureter/kidney/ urethral endometriosis is 40:5:1:1 (Citation9–11). Although ureteral endometriosis, as first described by Cullen in 1917 (Citation12), is rare (fewer than 1% of all UTE cases), it can asymptomatically lead to a compromised renal function secondary to hydronephrosis. Up to 47% of patients with ureteral endometriosis require nephrectomy at the time of diagnosis (Citation13–14). There are two types of ureteral endometriosis: Intrinsic and extrinsic. Extrinsic is the most common, accounting for 80% of cases of ureteral endometriosis, and is characterized by ectopic endometrial tissue involving the ureteral adventitia or surrounding connective tissues. Intrinsic ureteral endometriosis (20% of all cases) involves the uroepithelial and submucosal layers. Intrinsic and extrinsic ureteral endometriosis may both be present in the same individual, and either type may present with other foci of endometriosis (Citation10,Citation15–18).

Although ureteral endometriosis can cause flank pain and gross hematuria in some patients, in more than 50% of cases there are nonspecific symptoms or no symptoms at all; thus, there are often delays in diagnosis leading to substantial morbidity (Citation10,Citation19). Moreover, this condition is not always recognized by laparoscopy (Citation20). In addition, there are no specific diagnostic tests for ureteral endometriosis and therefore the diagnosis requires a high index of suspicion. The diagnostic tests currently used include ureteroscopy with endoluminal ultrasound, laparoscopy, computerized tomography, pelvic ultrasound, and excretory urography (Citation10). However, the diagnosis of ureteral endometriosis is often made incidentally during laparoscopy. Although medical treatment can reduce symptoms it is often unsatisfactory and results in side effects and a high recurrence rate (Citation21–23). Research has shown that surgical treatment of DIE is recommended for symptomatic disease resulting in compromised quality of life. Complete excision of the affected area seems to provide long-term pain relief and improved quality of life with a low recurrence rate in most patients with DIE (Citation24–28).

Following the first case of laparoscopic ureteral resection and ureteroureterostomy for endometriosis published by Nezhat et al. in 1992 (Citation29), a few small studies have confirmed the feasibility of laparoscopic ureteral resection for endometriosis. A variety of treatment options are available for ureteral strictures. Short distal ureteric defects can be treated by ureteroneocystostomy or end-to-end anastomosis. In cases of longer segments of ureteric disease more complex reconstrutive techniques, such as vesicopsoas hitch, Boari-flap, ileal ureteral substitution or autotransplantation are required (Citation30).

With regard to the laparoscopic approach, Rassweiler et al. (Citation31) have completed a retrospective comparison of laparoscopic vesicopsoas-hitch (with or without Boari-flap technique) with open ureteral reimplatation. They concluded that laparoscopic ureteral implantation is a feasible procedure with functional outcomes comparable to open surgery.

Here we report our experience in laparoscopic treatment of distal ureteral endometriosis with resection of the involved segment, ureteroneocystostomy, and vesicopsoas-hitch.

Material and methods

We retrospectively reviewed the data of all patients with DIE referred to our institution and treated with surgery from January 2001 to July 2008. Only patients with severe stenosis and hydroureteronephrosis requiring ureteral resection and ureteroneocystostomy with vesicopsoas-hitch were included. Cases of external endometriosis in which the lesion was treated by simple ureterolysis were excluded. All patients were investigated by CT scan, abdominal ultrasonography, and intravenous pyelogram (IVP). During laparoscopy, the entire course of both ureters was evaluated via retroperitoneal dissection.

The following data were collected for each patient: Age, parity, symptoms, diagnostic test results, previous medical and surgical treatment, intraoperative findings, associated operative procedures, operating room time, hospital stay, intraoperative and postoperative complications, concurrent disease, and symptom recurrence at follow-up.

All patients received detailed information regarding the risks and benefits of the technique and provided informed written consent. No mechanical bowel preparation was used, and perioperative antibiotic prophylaxis was given in all cases.

Surgical technique

The laparoscopic procedure was performed with the patient in the Lloyd-Davis position. Pneumoperitoneum was induced with a Veress needle. After the introduction of a 10-mm, 30° laparoscope in the right paraumbilical position, two additional trocars (10- and 12-mm) were placed in the right hypochondrium and right iliac fossa as for standard triangulation for left colon and rectal surgery. Another 5-mm trocar was placed selectively in the left abdomen. The procedure began with adhesiolysis, ovarian cystectomy as required and excision of peritoneal implants of endometriosis.

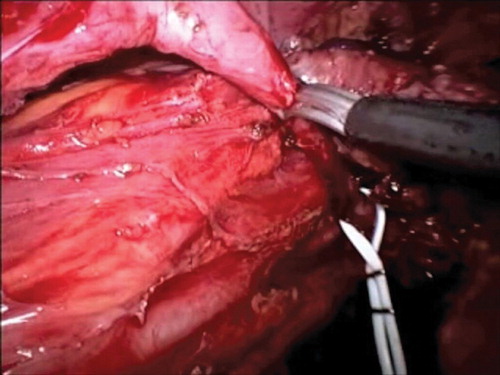

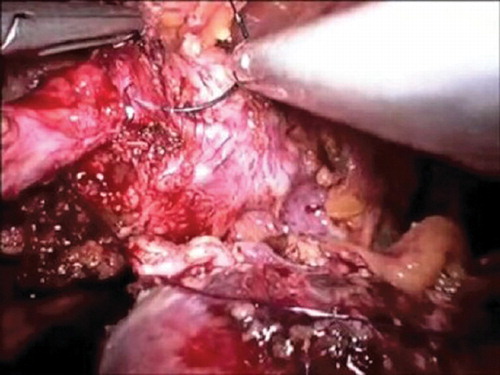

The operation was performed with a harmonic scalpel (Ultracision, Ethicon Endosurgery, Cincinnati, OH, USA). The patient was placed in an anti-Trendelenburg position for the mobilization of the descending and sigmoid colon and the detachment of Gerota's fascia from Toldt's fascia. The gonadal vessels and the left ureter were identified, and the uterosacral cardinal ligaments and rectovaginal septum were carefully evaluated. During mobilization of the mesorectum, care was taken to avoid damaging the underlying hypogastric nerve plexus without breaching the Heald's Fascia. The ureters were isolated up to the crossing with the uterine vessels, and then retroperitoneal mobilization was carried out from the sacral promontory. A bladder flap was created by vescical dissection and opening of the space of Retzius. The diseased ureteral segment was then excised (), the psoas muscle exposed and consequently the bladder secured to the muscle tendon. Following intraoperative insertion of an 8F double-J ureteral stent (occasionally with the aid of a cystoscope), an ureterocystoneostomy was fashioned using two continuous 4-0 PDS® sutures or alternatively four cardinal stitches (), as from modified Lich-Gregoir anti reflux technique. A Jackson-Pratt drain was placed in the pelvis.

Results

Between January 2001 and July 2008, 703 patients underwent laparoscopy for endometriosis. Of these, 155 (22.04%) were affected by DIE. Six (2.49%) patients had a left UTE, necessitating ureteral resection and ureteroneocystostomy with vesicopsoas-hitch. Patient characteristics are shown in .

Table I. Characteristics of the study population.

Only three patients presented with specific urinary symptoms: All had flank pain, and two had hematuria. Both cases with hematuria had concomitant bladder endometriosis. The remaining three patients had no specific urinary symptoms. In four of the six patients, UTE was diagnosed during previous laparoscopies performed at other institutions. All four patients had a positive IVP and a positive CT scan that showed a pelvic ureteral stenosis with left hydroureteronephrosis. For the other two patients, a diagnosis of hydroureteronephrosis was made by CT scan, and further diagnostic laparoscopy confirmed the presence of DIE. One of these patients underwent left percutaneous nephrostomy, and the other underwent ureteral endoscopic stent placement.

Laparoscopy confirmed left ureteral stenosis in all cases. All procedures were performed fully laparoscopically, and a double-J stent was applied during surgery. Three patients had partial bladder resection and two had rectal anterior resection.

The mean operating room time was 320 min (range 250–440). There were no intraoperative or postoperative complications. The mean length of stay was 8.3 days (range 7–10). All patients had a cystogram performed one week after surgery prior to Foley catheter removal and there were no cases of radiological extravasation of contrast The Jackson-Pratt drain was removed the day after the Foley catheter. The double-J stent was removed after 30 days.

Histopathological examination showed extrinsic endometriosis with the presence of fibrotic and inflammatory tissue in four cases and intrinsic endometriosis in two cases. All patients were followed up at one, three, six, and twelve months post-surgery with clinical examination, hematological tests, and abdominal ultrasound scan. After one year, patients had regular outpatient assessments annually. Each patient underwent IVP three months after surgery, and there were no cases with pathological findings ( and ). The median follow-up time was 38 months (range 12–56). There were no recurrences at follow-up in the study period, and the three patients who had previously had flank pain became asymptomatic.

Discussion

UTE is characterized by the presence of endometrial glands and stroma in or around the urinary bladder wall, ureters, urethra, and kidneys (Citation8). A high index of suspicion for ureteral endometriosis is necessary in order to avoid delays in diagnosis and prevent impairment of the urinary excretory system. The most effective method for detecting early ureteral involvement remains controversial.

Ureteral resection and ureteroneocystostomy with vesicopsoas is a surgical procedure usually performed via laparotomy (Citation32). Recent studies have reported that this technique provides positive long-term results; in addition, it is associated with minimal complications and a high success rate for the treatment of lower ureteral disease (Citation33). Reported side effects include injury to the femoral nerve branches (mainly the genito-femoral nerve) during placement of the psoas muscle sutures. Due to magnification, the laparoscopic technique offers an improved view and allows more accurate exposure, identification, and dissection of the involved areas in the pelvis, retroperitoneal space, and lower urinary tract. Moreover, a laparoscopic approach could reduce the associated pelvic pain and the length of hospitalization.

Research suggests that surgical treatment of DIE is recommended when the disease is symptomatic and affects the woman's quality of life. The present study shows that laparoscopic segmental ureteral resection with ureteroneocystostomy is technically feasible and represents a valid alternative to open surgery for patients requiring distal ureteral resection for endometriosis.

We had no intra- or postoperative complications and no disease recurrence at a median follow-up of 38 months. All patients had a normal IVP three months after surgery and were symptom-free at follow-up.

Our series confirms that the distal portion of the left ureter is more frequently affected by endometriosis than the contralateral ureter and that specific urinary symptoms are often absent.

Histological examination indicated that intrinsic endometriosis occurred in two cases (33%). This is higher than the percentage described by other researchers; however, our study included only severe cases that required ureteral resection.

Some studies support the use of ureterolysis for extrinsic endometriosis as a safe and effective technique even when moderate or severe hydroureteronephrosis is present (Citation20,Citation32). Others maintain that a ureteral resection should be performed in all cases of hydroureteronephrosis. In cases of intrinsic endometriosis it is generally accepted that a ureteral resection is mandatory, along with primary ureteroureterostomy or ureteral reimplantation with or without a vesicopsoas hitch (Citation10,Citation32,Citation34). It is important to achieve sufficient ureteral mobilization to obtain a tension-free anastomosis, and a vesicopsoas hitch procedure may be needed. Ureteral resection is usually performed via a laparotomic approach (Citation32).

The largest series of ureterolysis, published in 2006 by Ghezzi et al., reports a 15% recurrence rate. It also recommends that patients should be warned about the risk of further interventions and progressive renal failure, along with the need for close follow-up (Citation20). Our opinion, supported by other reports, is that simple ureterolysis is an effective technique in cases of extrinsic ureteral endometriosis when not associated with hydroureteronephrosis.

Ureteroureterostomy has been described as another possible reconstructive technique following resection, but we consider the ureteroneocystostomy with vesicopsoas a safer technique as it prevents stenosis as well as traction on the suture.

With regard to ureteral resection followed by reimplantation, a variety of techniques have been described in the literature and we report our successful series of laparoscopic reimplantation with modified Lich-Gregoir technique and vesicopsoas-hitch.

Unlike short distal ureteric defects which are suitable to an end-to-end anastomosis or ureteroneocystostomy, the cases with longer defects are more challenging and require more complex reconstructive procedures, such as the vesicopsoas-hitch technique, in order to obtain a tension-free vesicoureteral anastomosis.

The effectiveness of the psoas hitch and ureteral reimplantation in open surgery has been proven by multiple reports in the literature (Citation35–37). Gozen et al. (Citation38) reported their series of laparoscopic psoas hitch and concluded that it is a versatile procedure with multiple indications and associated with excellent results.

There are also other reconstructive techniques described in the literature which use replacements with bowel segments or bladder flaps (Citation30,Citation39).

Although we have no personal experience with laparoscopic bladder flap procedures, there are report in literature suggesting that combined vesicopsoas-hitch with Boari-flap technique is safe and associated with minimal complications in the treatment of wide defects of the distal and mid third of the ureter (Citation30, Citation40,Citation41). Also Rassweiler et al. (Citation31), in a retrospective comparison with open surgery, report a functional success rate of 10 out of 10 in the laparoscopic group.

With regard to the extravesical Lich-Gregoir technique, it is commonly used in the management of vesicoureteral reflux in pediatric patients and in renal transplant surgery (Citation42,Citation43). Gozen et al. (Citation38) report a successful series of five laparoscopic non-refluxing extravesical Lich-Gregoir reimplantations with no intra- or postoperative complications and a 100% success rate in accordance with previous literature for open surgery.

In conclusion, we recommend that patients with DIE should be referred to specialized centers with extensive experience in the laparoscopic management of DIE. We also suggest that all cases of DIE, especially those with uterosacral ligament or rectovaginal septum involvement, should undergo dissection and inspection of both ureters in order to avoid further complications. The laparoscopic approach represents a safe, minimally invasive, and effective option for the management of UTE also in cases requiring ureteral reimplantation. We consider the laparoscopic Lich-Gregoire with vesicopsoas-hitch technique the most effective laparoscopic reconstructive procedure; although it is technically challenging and requires high laparoscopic skills and should therefore be carried out only in specialist centers.

Large multicenter studies are needed to further support these findings and improve our understanding of this uncommon yet debilitating disease.

Acknowledgement

We would like to express our gratitude to IHTSC for editing support.

Declaration of interest: The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

References

- Weed JC, Ray JE. Endometriosis of the bowel. Obstet Gynecol. 1987;69:727–30.

- Bazot M, Darai E, Hourani R, Deep pelvic endometriosis: MR imaging for diagnosis and prediction of extension of disease. Radiology 2004;232:379–89.

- Darai E, Thomassin I, Barranger E, Feasibility and clinical outcome of laparoscopic colorectal resection for endometriosis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;192:394–400.

- Donnez J, Nisolle M, Casanas-Roux F. Three-dimensional architectures of peritoneal endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 1992;57:980–3.

- Kavallaris A, Kohler C, Kuhne-Heid R, Schneider A. Histopathological extent of rectal invasion by rectovaginal endometriosis. Hum Reprod. 2003;18:1323–7.

- Cornillie FJ, Oosterlynck D, Lauweryns JM, Koninckx PR. Deeply infiltrating pelvic endometriosis: histology and clinical significance. Fertil Steril. 1990;53:978–83.

- Koninckx PR, Mueleman C, Demeyere S, Lesaffre E, Cornillie FJ. Suggestive evidence that pelvic endometriosis is a progressive disease, whereas deeply infiltrating endometriosis is associated with pelvic pain. Fertil Steril. 1991;55:759–65.

- Gustilo-Ashby A, Paradiso M. Treatment of urinary tract endometriosis. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2006;13:559–65.

- Seracchioli R, Mabrouk M, Importance of Retroperitoneal Ureteric Evaluation in Cases of Deep Infiltrating Endometriosis. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2008;15:435–9.

- Yohannes P. Ureteral endometriosis. J Urol. 2003;170:20–5.

- Al Khawaja, Tan PH Ureteral endometriosis: clinicopathological and immunohistochemical study of 7 cases. Hum Pathol. 2008;39:954–9.

- Cullen TS. Adenomyoma of the tect-vaginal septum. Bull Johns Hopkins Hosp. 1917;28:343.

- Nezhat CH, Malik S, Laparoscopic ureteroneocystostomy and vesicopsoas hitch for infiltrative endometriosis. JSLS 2004:8:3–7.

- Klein RS, Cattolica EV. Ureteral endometriosis. Urology 1979;13:477–82.

- Takeuchi S, Minoura H, Toyoda N, Ichio T, Hirano H, Sugiyama Y. Intrinsic ureteric involvement by endometriosis: a case report. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 1997;23:273.

- Stanley KE Jr, Utz DC, Dockerty MB. Clinically significant endometriosis of the urinary tract. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1965;120:491.

- Yates-Bell AL, Molland EA, Pryor JP. Endometriosis of the ureter. Br J Urol. 1972;44:58.

- Pollack HM, Willis JS. Radiographic features of ureteral endometriosis. Am J Roentgenol. 1978;131:627–31.

- Comiter CV. Endometriosis of the urinary tract. Urol Clin North Am. 2002;29:625–35.

- Ghezzi F, Outcome of laparoscopic ureterolysis for ureteral endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 2006;86:418–22.

- Stillwell TJ, Kramer SA, Lee RA. Endometriosis of ureter. Urology 1986; 28:81.

- Bailey HR, Ott MT, Hartendorp P. Aggressive surgical management for advanced colorectal endometriosis. Dis Colon Rectum 1994;37:747–53.

- Ling FW. Randomized controlled trial of depot leuprolide in patients with chronic pelvic pain and clinically suspected endometriosis. Pelvic Pain Study Group. Obstet Gynecol. 1999;93:51–8.

- Chapron C, Jacobs S, Dubuisson JB, Vieira M, Liaras E, Fauconnier A. Laparoscopically assisted vaginal management of deep endometriosis infiltrating the rectovaginal septum. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2001;80:349–54.

- Preziosi G, Cristaldi M, Angelini L. Intestinal obstruction secondary to endometriosis: a rare case of synchronous bowel localization. Surg Oncol. 2007;16Suppl 1:S161–3.

- Busacca M, Bianchi S, Agnoli B, Follow up of laparoscopic treatment of stage III-IV endometriosis. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 1999;6:55–8.

- Chapron C, Dubuisson JB, Fritel X, Operative management of deep endometriosis infiltrating the uterosacral ligaments. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 1999;6:31–7.

- Garry R, Clayton R, Hawe J. The effect of endometriosis and its radical laparoscopic excision on quality of life indicators. BJOG 2000;107:44–54.

- Nezhat C, Nezhat F, Green B. Laparoscopic treatment of obstructed ureter due to endometriosis by resection and ureteroureterostomy: a case report. J Urol. 1992;148:865.

- Streem SB, Franke JJ, Smith JA. Surgery of the ureter 7th ed. In: Walsh PC, Retik AD, Vaughan Jr ED, editors. Campbell's urology, Vol.3. Philadelphia: WB Saunders 2003:2327.

- Rassweiler JJ, Gozen AS, Ureteral Reimplantation for Management of Ureteral Strictures: A Retrospective Comparison of Laparoscopic and Open Techniques European urology 2007;51:512–23.

- Frenna V, Santos L, Ohana E, Bailey C, Wattiez A. Laparoscopic management of ureteral endometriosis: our experience. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2007;14:169–71.

- Mathews R, Marshall F. Versatility of the adult psoas hitch ureteral reimplantation.J Urol. 1997;158:2078–82.

- Antonelli A, Simeone C, Clinical aspects and surgical treatment of urinary tract endometriosis: our experience with 31 cases. Eur Urol. 2006;49:1093–7.

- Riedmiller H, Becht E, Hertle L, Jacobi G, Hohenfellner R. Psoas-hitch ureteroneocystostomy: experience with 181 cases. Eur Urol. 1984;10:145–50.

- Ahn M, Laughlin KR. Psoas Hitch ureteral reimplantation in adults—analysis of a modified technique and timing of repair. Urology 2001;58:184–7.

- Benson MC, Ring KS, Olsson CA. Ureteral reconstruction and bypass: experience with ileal interposition, the Boari flappsoas hitch and autotransplantation. J Urol. 1990;143:20–3.

- Gozen AS, Cresswell J, Laparoscopic ureteral reimplantation: prospective evaluation of medium-term results and current developments. World J Urol. 2010;28:221–6.

- Shalhav AL, Elbahnasy AM, Bercowsky E, Kovacs G, Brewer A, Maxwell KL, Laparoscopic replacement of urinary tract segments using biodegradable materials in a large animal model. J Endourol. 1999;13:241–4.

- Stief CG, Jonas U, Petry KU, Bektas H, Klempnauer J, Chavan A, Ureteric reconstruction. Br J Urol. 2003;91:138–42.

- Olsson CA, Norlen LJ. Combined Boari bladder flap-psoas bladder hitch procedure in ureteral replacement. Scand J Urol Nephrol 1986;20:279–84.

- Heidenreich A, Ozgur E, Becker T, Haupt G. Surgical management of vesicoureteral reflux in pediatric patients. World J Urol. 2004;22:96–106.

- Veale JL, Yew J, Gjertson DW, Smith CV, Singer JS, Rosenthal JT, Long-term comparative outcomes between 2 common ureteroneocystostomy techniques for renal transplantation. J Urol. 2007:177:632–6.