ABSTRACT

Background: Canada was the first country to develop legal mechanisms that allow for supported decision making, and little research has explored how decision making is supported in this context. This research aimed to understand how seven people with intellectual disabilities, living in two Canadian provinces, were supported with their decision making.

Method: The research used constructivist grounded theory methodology, interviewing and observing the decision making of seven people with mild to severe intellectual disabilities and 25 decision supporters.

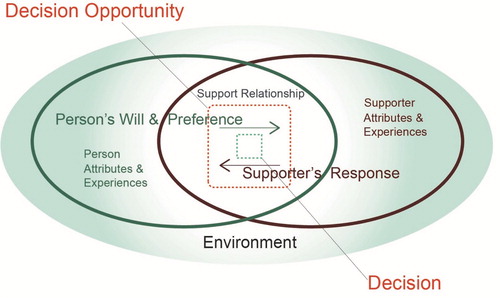

Results: A common process of decision-making support was discovered, involving dynamic interaction between the person’s will and preferences and supporters’ responses. This interaction was influenced by five factors: the experiences and attributes the person and their supporter brought to the process; the quality of their relationship; the decision-making environment and the nature and consequences of the decision.

Conclusion: The highly individualised and contextually dependent nature of decision-making support has implications for supported decision-making practice.

Supported decision making has two main aims, to enable people with cognitive disabilities to exercise their legal capacity (Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, Citation2014) and to determine their own lives (Shogren et al., Citation2017). The United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UNCRPD, Citation2006) promoted supported decision making, as a legal alternative to guardianship, and mechanism to reasonably accommodate people with cognitive disabilities to exercise their legal capacity (Donnelly, Citation2019; Harding & Taşciouğlu, Citation2018; Salzman, Citation2010). It has been widely discussed in relation to disability rights (Arstein-Kerslake, Citation2016; Carney, Citation2012; Dhanda, Citation2007; Dinerstein, Citation2012; Gooding, Citation2015; Lewis, Citation2010; Quinn, Citation2010; Szmukler, Citation2019), the subject of numerous reports of law reform agencies (Then et al., Citation2018) and in some cases adopted in legislationFootnote1 (Martinez-Pujalte, Citation2019).

In several Canadian provinces, legal mechanisms that create opportunities for supported decision making, such as Representation Agreements and Microboards, preceded the United Nations Convention on the Rights or Persons with Disabilities (CRPD), and have since been endorsed as examples of best practice (Stainton, Citation2016; UN Enable, Citation2006). Principles that underpinned these legally recognised supported decision-making schemes in Canada “emphasize the person’s right to self-determination and autonomy, the presumption of capacity, and the right to decision-making supports to enable equality before and under the law, without discrimination on the basis of disability” (Bach, Citation1998, p. 3). Few studies have explored actual practice of supported decision making in the context of Representation Agreements (James & Watts, Citation2014) or Microboards (Malette, Citation2002) and its alignment with the guiding principles (Nunnelley, Citation2015). Rather, the small body of research exploring supported decision-making in Canada has focused more generally on the uptake of legal mechanisms (Harrison, Citation2008; Nidus Personal Planning and Resource Centre, Citation2010; Nunnelley, Citation2015; Pedlar et al., Citation1999; Rutman & Taylor, Citation2009; Women’s Research Centre, Citation1994).

A growing body of research exploring how people with cognitive disability are supported with decision making outside legal supported decision-making schemes has focused on the experiences of specific groups; people with traumatic brain injury (Harding & Taşciouğlu, Citation2018; Knox et al., Citation2015; Knox et al., Citation2016a; Knox et al., Citation2016b), dementia (Fetherstonhaugh et al., Citation2016; Sinclair et al., Citation2018), severe or profound intellectual disabilities (Watson, Citation2016; Watson et al., Citation2019), family members (Sinclair et al., Citation2018) and workers in disability support services (Bigby et al., Citation2019; Harding & Taşciouğlu, Citation2018). Shogren et al.’s (Citation2017) review identified a wide range of contextual and environmental factors that shaped decision making for these populations, including decision-making experience, emotions, disability characteristics, accessibility of information, decision complexity, relationships with service providers, opportunities for decision making and family attitudes about decision making. Together these studies show that decision-making support is complex, difficult work (Bigby et al., Citation2019) that can be “burdensome” for supporters (Knox et al., Citation2015, p. 25) who apply a range of approaches (Sinclair et al., Citation2018) and at times defer to others (Harding & Taşciouğlu, Citation2018). People with severe or profound intellectual disability often rely on the responsiveness of their supporters to acknowledge, interpret and act on their will and preferences (Watson, Citation2016) and similarly, people with traumatic brain injury rely on supporters to assist them to “initiate” involvement with decision making (Knox et al., Citation2015, p. 26).

Support with decision making has been characterised as “assistive thinking”, acting as a cognitive “prosthesis” (Francis & Silvers, Citation2007, p. 487), whereby supporters co-construct the person’s will and preferences (Bach & Kerzner, Citation2010). Questions have been raised however, about whether it is possible for supporters to strip the process of their personality and interests (Silvers & Francis, Citation2009) and the risks of assigning meanings that reflect their own preferences (Johnson et al., Citation2012). The evidence to date suggests that a close, positive support relationship committed to the rights of the person and responsive to their will and preferences is central to good support for decision-making practice (Douglas & Bigby, Citation2020; Knox, Citation2016c; Watson, Citation2016).

Several conceptual models have been developed to assist supported decision-making practitioners (Douglas & Bigby, Citation2020; Shogren & Wehmeyer, Citation2015; Sinclair et al., Citation2018; Watson, Citation2016). Shogren and Wehmeyer’s (Citation2015) three-pronged framework considers the person’s 1) decision making abilities, 2) decision support needs and 3) the demands of their context. While the model embraces a social-ecological model of disability it considers decision-making ability as separate to the environmental demands and supports the person needs for decision making. This understanding is at odds with other proponents of supported decision making that see decision-making ability as determined and shaped by the supports and accommodations available to the person (Bach & Kerzner, Citation2010). This understanding is fundamental to ensuring people with severe or profound intellectual disabilities are not excluded from mechanisms of supported decision making (Watson, Citation2016).

Douglas and Bigby’s (Citation2020) support for decision-making practice framework has three elements: (a) seven iterative steps in the support for decision-making process, (b) three principles to guide support, and (c) multiple strategies for practice. Other support for decision-making models focus on the centrality of the relationship between the person and their supporter(s) as well as the impact of individual, relational, decisional, and external factors in the decision-making process (Sinclair et al., Citation2018; Watson, Citation2016).

This paper draws on a subset of data from a larger study, that aimed to understand how decision-making support is provided in the context of legal mechanisms that create opportunities for supported decision making in Canada.

Methodology

Social constructivism provided the theoretical framework – based on an understanding of reality as having multiple meanings, constructed through our experiences and interactions with others (Creswell, Citation2013). Constructivist researchers aim to understand “the complex world of lived experience from the viewpoint of those who live it” (Schwandt, Citation1994, p. 118) by exploring how individuals interact and the processes that shape these interactions (Creswell, Citation2013). Within this theoretical framework, the research utilised a grounded theory methodology as little was known about decision support and a process was thought to be embedded in it (Charmaz, Citation2006).

Participants

Two groups of participants were recruited: people with intellectual disabilities who were supported with decision making (central participants), and the people who provided the support (decision supporters). Participants were recruited through community-based disability support service networks in Vancouver, British Columbia using purposeful and theoretical sampling (Morse, Citation2007). Initially, inclusion criteria for central participants were 1) having an intellectual disability; 2) living in metropolitan Vancouver, British Columbia or surrounds; 3) be using a Representation Agreement (section 7) or Microboard to support decision making; and 4) being able to communicate verbally or using augmented and alternative communication (AAC) during an interview. A representation agreement is a legal document available to adults in British Columbia that authorises one or more personal supporters to become representatives to assist in the management of personal affairs and if necessary make decisions on their behalf in the case of illness, injury or disability. A microboard is a small group of committed family and friends that create a small non-profit society with a person to empower them and address their needs (Vela Microboard Association, Citation1997). As the study progressed, theoretical sampling was used to refine emerging tentative ideas (Charmaz, Citation2014). This meant recruiting of central participants with differing levels of intellectual disability, types of relationships with supporters, and whose use of their Representation Agreement or Microboard varied. It also led to the recruitment of a central participant from Ontario whose support network was engaging in decision-making support outside of formal legal mechanisms.

In total, seven central participants and 25 of their supporters participated. summarises their demographic information and data generated. Each participant was assigned a pseudonym to protect their anonymity. The study was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of the University.

Table 1. Demographic information and data generated from central participants and their supporters.

Consent to participate was sought from central participants using plain english information sheets and pictures. Supporters used this information to explain the research and link concepts to participants’ existing knowledge. Questions developed by Dye et al. (Citation2007) were used by the first author to assess each participant’s ability to provide informed consent. While proxy consent was obtained for three participants, assent was sought for all participants throughout the data generation process.

Data generation and analysis

Data generation, involving semi-structured interviews, participant observation and field notes, occurred between November 2013 and June 2014. The combination of observations and interviews helped to provide “a more complete and accurate account than either could alone” (Maxwell, Citation2012, p. 107). Semi-structured interviews enabled a balance between flexibility and structure (DiCicco-Bloom & Crabtree, Citation2006), ensuring participants were directing the telling of their stories (Mills et al., Citation2006) in a supportive context (Prosser & Bromley, Citation2012). An interview guide was used, which outlined general topics such as every day decision making, and exploratory prompts such as “Can you tell me about the support you provide (name) when you assist them with decision making?”.

After conducting the first interviews, the first author engaged in periods of participant observation of decision making in practice during which she wrote field notes capturing what occurred during interactions between central participants and supporters. Field notes included descriptions of people, events, and conversations as well as reflections on what had been observed (Taylor & Bogdan, Citation1998). A second interview provided an opportunity to ask about specific actions that had been observed and gather more focused information about the process of support (Maxwell, Citation2012).

Thirty-four interviews were conducted by the first author; five central participants and seven primary supporters were interviewed twice and 16 other supporters interviewed once. In total 104 h of participant observation occurred including all central participants and their networks, and over 170 pages of typed field notes were generated. All interviews were digitally recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Data analysis occurred over an extended period and involved initial, focused and theoretical coding. Initially, interview transcripts and field notes were coded by looking at each word, line and segment of data and developing preliminary “in vivo” codes (Charmaz, Citation2006, p. 56) that best captured the actions and incidents in the data. Initial coding used the terms as described by research participants to capture their ideas (e.g., “skin in the game”). These short, simple codes were written quickly in the margins of typed transcripts and field notes, though there were instances where it took time to find codes that fitted specific pieces of data well (Charmaz, Citation2006). For example, some simple codes that initially referred to supporter “influence” were later categorised as a range of supporter “responses”.

Research quality

The methods demonstrated the four quality criteria for grounded theory research proposed by Charmaz (Citation2014); “credibility, originality, resonance and usefulness” (p.337-338). For example, there was prolonged researcher engagement (eight months spent in Vancouver) and persistent observation of decision making (104 h). Data generated from semi-structured interviews was triangulated with the data generated from periods of participant observation enabling a deeper understanding of decision making in context. Member checking occurred during second interviews and peer debriefing was used to reflect on the researcher’s position. Regular supervision allowed for the interrogation of transcripts and field notes for methodological coherence. The use of a personal journal and memo writing enabled a rich description of research assumptions/limitations.

Findings

Decision support was a complex, dynamic and multifactorial process that started when a decision opportunity arose in the person’s life and was explored with their decision supporter. During this exploration the person expressed their will and preferences about the decision and their supporter responded. There was a dynamic interaction between the person’s will and preferences and their supporter’s responses all of which were influenced by five factors: (a) the experiences and attributes the person brought to the process; (b) the experiences and attributes of their supporter; (c) the nature of the support relationship; (d) the environment in which decision making occurred; and (e) the nature and consequences of the decision. The way that supporters responded during the process to the person’s will and preferences shaped the person’s agency and their control over the decision that was made. represents the process of decision-making support and the complex interaction between the two core elements (person’s will and preferences and their supporter’s responses) and the five influencing factors. The following sections use two examples of decision support to illustrate how the process was influenced by the five factors, and the different ways the process played out for the people who were supported depending on these factors.

Example 1. Does Cecily want to try swimming?

Person – attributes and experiences.

Cecily, a 49-year-old woman, loved “her fiancé David, the engagement ring he gave her, which she kept in a special box in her bedroom, going out for coffee with her sister Shirley on the weekend and Harry Mandel from Deal or No Deal.” Cecily enjoyed spending time with friends at her day program and the four women with whom she lived in a group home. Despite attempts by staff and family to encourage Cecily to try new things, she often preferred to stick with her existing weekly routine.

Supporter – perception of role

Lisa had fallen into her job as a disability support worker and “accidently” found her niche. She attempted to treat the people she supported in the group home as she would like to be treated in the same situation and believed her role as a support worker was to help Cecily be all that she “should and can be”. She said about the support she provided to Cecily:

… I can tweak here, tweak there, talk to you about this, talk to you about that.

Know when to be quiet and back off, you’ve had enough.

Lisa believed her role was to shape and frame information, to “empower” Cecily to make the best decision and “help guide her in a more healthy direction”. After many years working together, Lisa thought of Cecily as a friend who was very important to her.

Support relationship

Cecily and Lisa had known each other for over 12 years. Cecily was unable to discuss whether she trusted Lisa but her willingness to seek support from her in the day program environment when feeling insecure, and introduce her as someone important in her life, suggested she knew Lisa well and trusted her support. Lisa had developed a strong understanding of how Cecily comprehended information and the importance of breaking it down into “little steps”. She had learned the cues that helped her understand what Cecily wanted when she couldn’t say it in words. For example, she knew that sometimes when Cecily said no she didn’t really mean no.

Her first response tends to be no, or I can’t, I can’t. Everything’s critical, I can’t, I can’t … I learned through building rapport with her that it’s not always what she means. She could mean I can’t go right now. Or I want to finish my knitting, or I haven’t had a shower. But I learned that going out for dinner is a highlight for her. So no doesn’t mean no in that regard.

Environment – funding and service context.

As a staff member working in the group home, Lisa was under pressure to demonstrate she was meeting Cecily’s health needs adequately.

… in a licensed group home there are a lot of concerns … It's neglect if they don’t go to the dentist or they don’t see a doctor when they are sick and Cecily has a heart condition and so these things have to be addressed and kept on top of …

Decision opportunity

Cecily’s heart specialist, Dr Key, recommended changes to her diet and that she commence regular exercise such as swimming. Lisa believed swimming was “the only exercise” Cecily was “going to benefit from” and “the best thing for her”. She created a decision opportunity by inviting Cecily to join other members of the house who went on a weekly outing to the local swimming pool followed by dinner. Lisa was very aware of the serious consequences on Cecily’s heart condition of not exercising regularly.

Dynamic interaction between the person’s will and preferences and supporter’s response

In response to the invitation to participate, Cecily was “adamant”, saying “no God no, oh God no”. Cecily did not want to go swimming. In response, Lisa initially accepted Cecily’s will and preference. She said, “I heard no and we accommodated that in the beginning”. However, over time Lisa’s response changed, as she became frustrated at Cecily’s reluctance to try something new.

And a lot of the time for Cecily she will say no without knowing what she is saying no to. You know. I didn’t ask you to cut off your finger. We’re going swimming and then out for dinner.

Just come with me, put your bathing suit on, if you decide you don’t want to get in the water, don’t get in the water. But at least come with me and put your bathing suit on. And then if you don’t want to go you can sit with the lifeguard.

Decision

When Cecily eventually got to the swimming pool with her bathing suit on, she surprised everyone when she swam “like an Olympic star”. She was a strong swimmer, participating without “needing any prompts or praise. Once she got in she just did her laps no problem”. After the initial push, Cecily would willingly get her swimming bag ready, with her perfumes and shower gels, to go swimming each week.

Example 2: does Natalie want to quit?

Person – attributes and experiences

Natalie, a 28-year-old woman, was passionate about the environment and using technology. She was diagnosed with Leukaemia when she was three years of age and had a stroke aged 16 resulting in left-sided paralysis and significant speech, vision and memory impairments. With ongoing rehabilitation, she relearned to walk and talk and now relies on an electric wheelchair to travel medium to long distances.

Natalie needed a lot of support and encouragement to make decisions. She was perceived as a “people pleaser” who often felt “overwhelmed about making a decision”. It helped Natalie if complex decisions were broken into smaller bounded choices and she was asked questions to clarify her will and preferences. In recent years Natalie had experienced “quite a large weight gain” and was no longer able to stand “on a regular scale” to be weighed. Members of her Microboard were concerned about the long-term effects of the weight gain on her wellbeing given her medical history.

Supporter – perception of role

Annie was employed as a rehabilitation aide by Natalie’s parents to implement therapy programs, support her to access the community and develop life skills. She used music and humour to motivate Natalie to find her voice while doing physical therapy. Swimming enabled Natalie to “get a cardio workout” that was easy “on her joints, because she can’t walk” and Annie believed, “it goes without saying that swimming is very, very important [for her health]”.

Annie believed her role was to “always try and remain neutral” being careful not to impose her “preference on” Natalie. However, she also thought part of her role was supporting Natalie to accept boundaries set by her parents “we just have to work within what mum and dad said” and that if she could “make it seem like something is more of her idea, then it’s more readily welcomed”.

Annie was aware her word choice and body language could “influence” Natalie and tried to reduce this by using “self-analysis” and becoming clearer about her own “views” in relation to the proposed decision. Annie was strategic about eliciting Natalie’s views in order to minimise her influence on Natalie’s preferences.

I didn’t know how she felt about things so I was very careful not to tell her what I was thinking or feeling or what my stand was on anything. I always allow her to express her view first. And it was difficult because sometimes she would not want to do that because she was feeling insecure and she would rather hear what I thought before she said what she thought … it’s like gentle persistence in saying “no tell me what you think I’m really interested in what you have to say.”

Support relationship

Natalie and Annie had developed deep knowledge, respect and trust in one another over a period of 10 years. Natalie saw Annie as her therapist, friend and family member and when they were together, Annie moved between these roles constantly. They shared a familiar ease in each other’s company.

Environment – funding and service context

The decision-making environment was shaped by the family’s financial situation and the conditions of the funding Natalie received, which had been negotiated initially to pay for physical rehabilitation after her stroke. However, the health department had a continuing obligation to fund activities aimed at improving Natalie’s health. Her father explained:

… if Natalie wants to go swimming for instance, she is getting therapy from the rehab aide who will stand over her while she is swimming. The rehab aide also helps her in the shower and makes sure she gets down the stairs and into the pool safely. Now we’re talking health and safety and that falls within the purview of the health department. So, we can still definitely justify the funding.

Decision opportunity

About a year ago Natalie started to make excuses to avoid her long-term and regular swimming program, saying “I don’t want to go I’m cold” or “I’m tired.” In the warm weather, it was “too nice out I don’t want to go swimming” and when it was raining, “I don’t want to be in the pool it’s going to rain on me”. Annie wondered if Natalie wanted to stop swimming as a form of therapy and identified a decision opportunity about whether Natalie wanted to quit swimming.

Natalie was largely unaware of the consequences of ceasing swimming but Annie was mindful that weight gain increased Natalie’s risk of stroke and immobility. There was also the potential for Natalie to lose her individualised funding if she did not engage in physical therapy.

Dynamic interaction between the person’s will and preferences and supporter’s response

Annie asked Natalie in a “casual and easy” way that was not “intimidating, do you still care about this?” and Natalie responded that she still liked swimming. Annie sought to clarify Natalie’s will and preference by asking additional questions to understand her pattern of excuses. Natalie explained that the pool roof leaked when it rained, which meant the rain dripped on her when she was stretching at the end of the pool. When Annie asked her about winter she said “the pool’s cold” to which Annie empathised saying “I know it’s too cold for me to swim in winter”. Further exploration uncovered that Natalie didn’t want to swim indoors in summer because “it’s so nice out outside!”

After clarifying, Annie accepted Natalie’s will and preferences and thought that giving Natalie more options would help to clarify what she would do if she didn’t want to go swimming. Natalie had said she would like to go swimming in the indoor pool on cloudy days and no longer go there in winter. Annie supported Natalie to explore the possibility of going to an outdoor pool in the summer where they could do some personal training outside as well as play ball in the pool and generally have fun. When it was raining, Annie suggested she could plan some alternative therapy options from which Natalie could choose each week.

Decision

Natalie decided not to return to the indoor swimming pool during winter and was excited to try other therapy options until the weather improved. Annie asked Natalie to communicate the decision they reached together to her parents, which would allow everybody to stay “on the same page”. Natalie’s father respected her decision.

Reflecting on the decision-making process

These two examples both explored decision opportunities about swimming that involved concerns about the health of the person, support by paid staff in relationships characterised as mutually trusting and respectful, with shared mutual knowledge developed over years. There were however some significant differences. Participants brought to the process different attributes, experiences, values and priorities that shaped how it unfolded. Cecily brought a tendency towards routine and reluctance to try new things. Whereas, Natalie brought a tendency towards pleasing others and could become overwhelmed when making decisions. The two decision supporters brought different perceptions about their role. Lisa believed her role was to “help guide [Cecily] in a more healthy direction”, perceiving Cecily’s will and preferences as something to be shaped or “tweak[ed]”. Whereas, Annie believed her role was to “always try and remain neutral” and perceived Natalie’s will and preferences as vulnerable to influence.

Different environmental pressures, in these example service and funding contexts, helped to shape the process. Annie knew that Natalie’s individualised funding might be threatened if she stopped participating in rehabilitation activities, and as a group home employee Lisa needed to ensure Cecily’s heart condition and weight were being managed in line with medical recommendations.

The two examples demonstrate the recursive rather than linear nature of the process of decision-making support. The views of the person and their supporter bounce backwards and forwards, forming a dynamic interaction between the person’s will and preferences and their supporter’s responses. Sometimes these dynamic interactions changed the person’s will and preferences, in the case of Cecily, and sometimes they didn’t as in Natalie’s case. Sometimes, the interactions helped the person to clarify their will and preferences and articulate their decision more clearly, as in Natalie’s case where it became clearer why she didn’t want to swim. Sometimes, the interactions changed the supporter’s response, such as when Lisa moved from accepting Cecily’s will and preference to actively trying to change them. Clearly, in each example, both expression of will and preferences and responses were influenced by the nature of the decision, the attributes and experiences of person and supporter, their relationship and the environment.

The way supporters responded during the process influenced the outcome of the decision process for the person. For example, Natalie’s agency was increased by the way that Annie supported Natalie to clarify her will and preferences by asking questions, acknowledging her concerns, providing more options, and then accepting her preferences about the decision. Whereas Lisa’s responses gave Cecily little agency about the decision, as her preferences were not accepted and attempts were made to change her mind.

Discussion

Support is contextually dependent

The two examples illustrate the diversity of attributes and experiences brought to decision-making processes. Central participants brought different tendencies, skills and experiences of decision making. Supporters brought different values and beliefs, perceptions of decision-making ability and understanding of their role. There were also differences in support relationships, funding and service contexts as well as risks associated with the decision. People with intellectual disabilities were supported through a wide range of strategies that were shaped by these influencing factors.

The time over which decision support occurred varied; sometimes it was brief and other times stretched over months. The intensity and type of support also varied, taking many different forms; planning and breaking things down, enabling and clarifying understanding, minimising stress and anxiety, choosing when and how to discuss things, providing advice, helping problem solve, monitoring the person’s safety, explaining risks, creating opportunities to try new things, interpreting non-verbal communication, learning the person’s unique language, and interpreting the person’s will and preferences through observing the person’s reactions.

The findings of this research suggest that although at a conceptual level the processes of decision-making support are similar, the way it plays out for each individual and decision is unique because of the diverse composition of factors involved in the process. As such, it is challenging to prescribe what effective decision support is, as it needs to be determined in light of each person’s unique situation and the broader context in which decision making occurs.

Challenge of neutrality

Participants in this study, like many people with disabilities, were dependent on the support of others to identify and express their will and preferences (Series, Citation2015; Skowron, Citation2019; Watson, Citation2016). The findings demonstrate the influence of the different personal experiences and attributes supporters brought to the process, which together with the other influencing factors shaped how they helped the person identify, clarify and act on their will and preferences. This aspect of the model aligns with Watson’s research (Citation2016) which conceptualises decision-making support for people with severe to profound intellectual disability as contingent on the ability of supporters to interpret and act on the person’s expressions of will and preference.

Emerging research into the practice of supported decision making suggests it can be difficult for supporters to remain “neutral in decision support relationships” (Bigby et al., Citation2019, p. 10) and provide “prosthetic rationality” without substituting their own ideas (Silvers & Francis, Citation2009, p. 485). The findings of the present study suggest one reason for this may be the way that personal attributes and experiences are entwined in the decision-making support process. Supporters may not be explicitly aware of their own attributes or the influence of these on the nature of their supports. Thus remaining “neutral” requires significant capacity for self-reflection and the ability to actively separate their personal preferences and interests from the support process.

Exploration of undue influence

This study found instances of supporters trying to change the person’s will and preferences during the decision-making process. They used gently pursuasive strategies such as, verbal encouragement, presenting an idea as if it came from the person, bargaining and offering rewards, to influence an individual’s preferences. However, there were occasions when strategies were more heavy handed, and supporters used their tone of voice, withheld information or framed it in particular ways in order to influence preferences. All of these strategies might be perceived as dimishing the agency of the individual, resulting in a decision that deviated from their will and preferences. As such, they can be construed as undue influence or informal coercion. In the context of psychosocial disability this has been conceptualised as a “milder form” of influence than coercion and includes “request[s], reasoning, persuasion, barter, bargaining, gentle prodding, enticement, selective information, manipulation, deceiving, blackmail, threat and even various forms of physical force” (Rathner, Citation1998, p. 186).

The findings of the present study suggest that undue influence is not associated with a particular characterisation of the support relationship. Even in support relationships characterised by mutual knowledge, trust and respect, there were times when supporters influenced the person’s decision making. This is contrary to the suggestion that undue influence occurs when the support relationship is characterised by “domination”(Arstein-Kerslake, Citation2016, p. 89) and an imbalance of power rather than an “empowering dependency” (p.90).

Types of self-reflection and review

These findings, together with earlier research, suggest self-reflection and review may be useful tools to help supporters to be more self-aware and minimise practices of undue influence (Douglas & Bigby, Citation2020; Knox, Citation2016c). The process of decision-making support identified helps to illustrate the factors that influence supporters and suggests three types of reflection may be beneficial. First, self-reflection prior to engagement in the process may assist supporters to be more aware of the potential influence of their own attributes and experiences on those they support. For example, a supporter may be very risk averse because of difficult past experiences and awareness of this tendency will help to mitigate its influence when supporting someone with decisions that involve risk. Second, reflection during the process may improve supporters’ abilities to more consciously identify and challenge the individual, relational, decisional and environmental factors shaping their support. For example, a supporter may become aware that she is allowing the judgement of family members to influence her feelings about a decision opportunity for the person. By stepping back from the situation and reflecting on this she may be more able to withstand such pressure. Finally, reflection after the process can be used to review the outcome for the person and others. Such reflection may allow the supporter to identify the extent to which the process increased or decreased the agency of the person and was directed by their will and preferences. Decisions are not made in isolation and often lead to other decisions (Bigby et al., Citation2017b). Reviewing the process will assist in identifying associated decisions as well as the consequences of the decision for the person’s life. It could also help determine whether the process facilitated the development of decision-making skills and how it might be improved in the future.

Limitations and recommendations for future research

The inclusion of central participants with a range of intellectual disabilities was a strength of the broader doctoral research from which this data set was collected. However, the two examples used to illustrate the model of decision-making support developed from the research do not reflect this range. The examples were chosen because they share other important similarities (decision and relationship type) and differences (attributes, experiences and environmental constraints). As such, a limitation of the findings, as presented, is that they do not include the rich experiences of central participants who had severe to profound intellectual disabilities. A more thorough examination of how their experiences informed the development of the model, including a detailed example illustrating the experience of Emily and her supporter Sally, can be found in the thesis (Browning, Citation2018).

While the experiences of central participants and their supporters described in this study were unique, the applicability of the process identified and its influencing factors can be explored further with other groups and contexts of decision support. Resource constraints limited the number of participants and their location to two provinces in Canada. In general, participants were similar in terms of the quality of their support relationships and cultural background. Given the research that shows cultural context shapes the expression of preference in choice making (Savani et al., Citation2008) and how people understand the outcomes of decision making (Weber & Hsee, Citation2000), future research should include people from more diverse cultures. It would also benefit from exploring the impact different legal mechanisms, that recognise supported decision making, have on the decision-making context.

This research identified that the perception decision supporters had of their role was a personal attribute that contributed to how supporters responded to the person’s will and preferences. Future research would benefit from exploring the impact of other personal attributes such as prior education in supported decision-making practice and risk tolerance.

Conclusion

The aim of this study was to explore how people with intellectual disabilities were supported with their decision making in Canada. The findings have helped to broaden understanding of supporter neutrality and undue influence, and the complex, dynamic and multifactorial nature of decision support. The process uncovered demonstrates the contextually dependent nature of decision support. By identifying the individual, relational, decisional and environmental factors that influence the process it may assist supporters to engage in self-reflection and review.

Acknowledgement

This research was supported by an Australian postgraduate research scholarship.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 Legislation that legally recognises supported decision-making has been enacted in a number of countries including Argentina, Australia, Canada, India, Ireland, Peru and United States of America.

References

- Arstein-Kerslake, A. (2016). An empowering dependency: Exploring support for the exercise of legal capacity. Scandinavian Journal of Disability Research, 18(1), 77–92. https://doi.org/10.1080/15017419.2014.941926

- Arstein-Kerslake, A. (2016). Legal capacity and supported decision-making: Respecting rights and empowering people. SSRN Electronic Journal, https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2818153

- Bach, M. (1998). Securing self-determination: Building the agenda in Canada. http://www.communitylivingbc.ca/what_we_do/innovation/pdf/Securing_the_Agenda_for_Self-Determination.pdf

- Bach, M., & Kerzner, L. (2010). A new paradigm for protecting autonomy and the right to legal capacity (Report prepared for the Law Commission of Ontario) http://www.lco-cdo.org/en/disabilities-call-for-papers-bach-kerzner

- Bigby, C., Douglas, J., Carney, T., Then, S., Wiesel, I., & Smith, E. (2017b). Delivering decision-making support to people with cognitive disability: What has been learned from pilot programs in Australia from 2010-2015. Australian Journal of Social Issues, 52(3), 222–240. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajs4.19

- Bigby, C., Whiteside, M., & Douglas, J. (2019). Providing support for decision making to adults with intellectual disabilities: Perspectives of family members and workers in disability support services. Journal of Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 44(4), 396–409. https://doi.org/10.3109/13668250.2017.1378873

- Browning, M. (2018). Developing an understanding of supported decision-making practice in Canada: The experiences of people with intellectual disabilities and their supporters [Doctoral dissertation]. La Trobe University.

- Carney, T. (2012). Guardianship, citizenship, and theorizing substitute-decision making law. In I. Doron, & A. Soden (Eds.), Beyond Elder Law: New Directions in Law and Ageing (pp. 1–17). Springer Verlag.

- Charmaz, C. (2006). Constructing grounded theory: A practical guide through qualitative analysis. Sage Publications.

- Charmaz, C. (2014). Constructing grounded theory (2nd ed.). Sage Publications.

- Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. (2014). General Comment No 1 (2014) Article 12: Equal recognition before the law. Geneva. https://documents-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/G14/031/20/PDF/G1403120.pdf?OpenElement

- Creswell, J. W. (2013). Qualitative inquiry and research design (3rd ed.). Sage Publications.

- Dhanda, A. (2007). Legal capacity in the disability rights convention: Stranglehold of the past or lodestar for the future? Syracuse Journal International Law and Commerce, 34, 429–462.

- DiCicco-Bloom, B., & Crabtree, B. F. (2006). The qualitative research interview. Medical Education, 40(4), 314–321. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2929.2006.02418.x

- Dinerstein, R. (2012). Implementing legal capacity under Article 12 of the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with disabilities: The difficult road from guardianship to supported decision-making. Human Rights Brief, 19(2), 8–12.

- Donnelly, M. (2019). Deciding in dementia: The possibilities and limits of supported decision-making. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry, 66, 101466. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijlp.2019.101466

- Douglas, J., & Bigby, C. (2020). Development of an evidence-based practice framework to guide decision making support for people with cognitive impairment due to acquired brain injury or intellectual disability. Disability and Rehabilitation, 42(3), 434–441. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2018.1498546

- Dye, L., Hare, D. J., & Hendy, S. (2007). Capacity of people with intellectual disabilities to consent to take part in a research study. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 20(2), 168–174. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-3148.2006.00310.x

- Fetherstonhaugh, D., Tarzia, L., Bauer, M., Nay, R., & Beattie, E. (2016). “The red dress or the blue?” How do staff perceive that they support decision-making for people with dementia living in residential aged care facilities? Journal of Applied Gerontology, 35(2), 209–226. https://doi.org/10.1177/0733464814531089

- Francis, L. P., & Silvers, A. (2007). Liberalism and individually scripted ideas of the good: Meeting the challenge of dependent agency. Social Theory and Practice, 33(2), 311–334. https://doi.org/10.5840/soctheorpract200733229

- Gooding, P. (2015). Navigating the ‘flashing amber lights’ of the right to legal capacity in the United Nations convention of the rights of persons with disabilities: Responding to major concerns. Human Rights Law Review, 15(1), 45–71. https://doi.org/10.1093/hrlr/ngu045

- Harding, R., & Taşciouğlu, E. (2018). Supported decision-making from theory to practice: Implementing the right to enjoy legal capacity. Societies, 8(2), 25–39. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc8020025

- Harrison, W. (2008). Representation agreements in British Columbia: Who is using them and why? [Unpublished Master’s thesis]. Simon Fraser University.

- James, K., & Watts, L. (2014). Understanding the lived experiences of supported decision-making in Canada: Legal capacity, decision-making and guardianship (Report commissioned by the Law Commission of Ontario). https://www.lco-cdo.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/03/capacity-guardianship-commissioned-paper-ccel.pdf

- Johnson, H., Watson, J., Iacono, T., Bloomberg, K., & West, D. (2012). Assessing communication in people with severe-profound disabilities. Journal of Clinical Practice in Speech-Language, 14(2), 64–68. http://hdl.handle.net/10536/DRO/DU:30078913

- Knox, L. (2016c). The experience of being supported to participate in decision-making after severe traumatic brain injury [Doctoral dissertation]. La Trobe University.

- Knox, L., Douglas, J. M., & Bigby, C. (2015). ‘The biggest thing is trying to live for two people’: Spousal experiences of supporting decision-making participation for partners with TBI. Brain Injury, 29(6), 745–757. https://doi.org/10.3109/02699052.2015.1004753

- Knox, L., Douglas, J. M., & Bigby, C. (2016a). Becoming a decision-making supporter for someone with acquired cognitive disability following traumatic brain injury. Research and Practice in Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 3(1), 12–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/23297018.2015.1077341

- Knox, L., Douglas, J. M., & Bigby, C. (2016b). “I won’t be around forever”: understanding the decision-making experiences of adults with severe TBI and their parents. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation, 26(2), 236–260. https://doi.org/10.1080/09602011.2015.1019519

- Lewis, O. (2010). The expressive, educational and proactive roles of human rights: An analysis of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with disabilities. In B. McSherry, & P. Weller (Eds.), Rethinking rights-based mental health laws (pp. 97–128). Hart Publishing.

- Malette, P. (2002). Lifestyle quality and person centred support. Jeff, Janet, Stephanie and the microboard project. In S. Holburn, & P. M. Vietze (Eds.), Person centred planning research practice and future directions (pp. 151–179). Paul H Brookes Publishing.

- Martinez-Pujalte, A. (2019). Legal capacity and supported decision-making: Lessons from some recent legal reforms. Laws, 8(1), 4–26. https://doi.org/10.3390/laws8010004

- Maxwell, J. A. (2012). A realist approach for qualitative research. Sage Publications.

- Mills, J., Bonner, A., & Francis, K. (2006). Adopting a constructivist approach to grounded theory: Implications for research design. International Journal of Nursing Practice, 12(1), 8–13. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-172X.2006.00543.x

- Morse, J. M. (2007). Sampling in grounded theory. In A. Bryant, & K. Charmaz (Eds.), The Sage Handbook of grounded theory (pp. 229–244). Sage Publications.

- Nidus Personal Planning and Resource Centre. (2010). A study of personal planning in British Columbia: Representation agreements with standard powers. http://www.nidus.ca/?page_id=234

- Nunnelley, S. (2015). Personal support networks in practice and theory: Assessing the implications for supported decision-making law (Report commissioned by the Law Commission of Ontario). https://www.lco-cdo.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/capacity-guardianship-commissioned-paper-nunnelley.pdf

- Pedlar, A., Haworth, L., Hutchison, P., Taylor, A., & Dunn, P. (1999). A textured life: Empowerment and adults with developmental disabilities. Wilfrid Laurier University Press.

- Prosser, H., & Bromley, J. (2012). Interviewing people with intellectual disabilities. In E. Emerson, C. Hatton, K. Dickson, A. Caine, & J. Bromley (Eds.), Clinical Psychology and people with intellectual disabilities (2nd ed.) (pp. 107–120). John Wiley & Sons.

- Quinn, G. (2010). Personhood and legal capacity: Perspectives on the paradigm shift of article 12 CRPD [Presentation to HPOD Conference Harvard Law School]. http://www.nuigalway.ie/cdlp/documents/publications/Harvard Legal Capacity gq draft 2.doc

- Rathner, G. (1998). A plea against compulsory treatment of anorexia nervosa patients. In W. Vandereycken, & P. Beumont (Eds.), Treating eating Disorders: Ethical, legal and personal issues (Vol 1) (pp. 179–215). Athlone Press.

- Rutman, D., & Taylor, J. (2009). Experiences of adults living with Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder and their personal supporters in making and using a representation agreement: An analysis of representation agreements as a tool for supported decision-making for adults with FASD. http://www.nidus.ca/PDFs/Nidus_Research_RA_FASD_Project.pdf

- Salzman, L. (2010). Rethinking guardianship (again): Substituted decision-making as a violation of the integration mandate of title II of the Americans with disabilities Act. Cardozo legal studies research paper No 282. University of Colorado Law Review, 81, 157–245. http://lawreview.colorado.edu/wp-content/uploads/2013/11/10Salzman-FINAL_s.pdf

- Savani, K., Markus, H. R., & Conner, A. L. (2008). Let your preference be your guide? Preferences and choices are more tightly linked for North Americans than for Indians. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 95(4), 861–876. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0011618

- Schwandt, T. A. (1994). Constructivist, interpretivist approaches to human inquiry. In N. K. Denzin, & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), Handbook of qualitative research (pp. 118–138). Sage Publications.

- Series, L. (2015). Relationships, autonomy and legal capacity: Mental capacity and support paradigms. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry, 40(1), 80–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijlp.2015.04.010

- Shogren, K. A., & Wehmeyer, M. L. (2015). A framework for research and intervention design in supported decision-making. Inclusion, 3(1), 17–23. https://doi.org/10.1352/2326-6988-3.1.17

- Shogren, K. A., Wehmeyer, M. L., Lassman, H., & Forber-Pratt, A. J. (2017). Supported decision making: A synthesis of the literature across intellectual disability, mental health and ageing. Education and Training in Autism and Developmental Disabilities, 52(2), 144–157. https://doi.org/10.2307/26420386

- Silvers, A., & Francis, L. P. (2009). Thinking about the good: Reconfiguring liberal metaphysics (or not) for people with cognitive disabilities. Metaphilosophy, 40(3-4), 475–498. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9973.2009.01602.x

- Sinclair, C., Gersbach, K., Hogan, M., Bucks, R. S., Auret, K. A., Clayton, J. M., Agar, M., & Kurrle, S. (2018). How couples with dementia experience healthcare, lifestyle, and everyday decision-making. International Psychogeriatrics, 30(11), 1639–1647. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1041610218000741

- Skowron, P. (2019). Giving substance to ‘the best interpretation of will and preferences’. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry, 62, 125–134. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijlp.2018.12.001

- Stainton, T. (2016). Supported decision-making in Canada: Principles, policy and practice. Research and Practice in Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 3(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1080/23297018.2015.1063447

- Szmukler, G. (2019). “Capacity”, “best interests”, “will and preferences” and the UN convention on the rights of persons with disabilities. World Psychiatry, 18(1), 34–41. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20584

- Taylor, S. J., & Bogdan, R. (1998). Introduction to qualitative methods: A guidebook and resource (3rd ed.). John Wiley & Sons.

- Then, S., Carney, T., Bigby, C., & Douglas, J. (2018). Supporting decision-making of adults with cognitive disabilities: The role of law reform agencies: Recommendations, rationales and influence. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry, 61, 64–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijlp.2018.09.001

- UN Enable. (2006). Chapter Six: From provisions to practice: implementing the convention. Legal capacity and supported decision making. http://www.un.org/disabilities/ default.asp?id = 242 on 9 January 2013

- United Nations [UNCRPD]. (2006). The Convention of the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. http://www.un.org/disabilities/convention/conventionfull.shtml

- Vela Microboard Association. (1997). Microboards [brochure]. http://www.microboard.org/PDF/principles%20and%20functions.pdf

- Watson, J. (2016). Assumptions of decision-making capacity: The role supporter attitudes play in the realisation of Article 12 for people with severe or profound intellectual disability. Laws, 5(1), 6–9. https://doi.org/10.3390/laws5010006

- Watson, J., Voss, H., & Bloomer, M. J. (2019). Placing the preferences of people with profound intellectual and multiple disabilities at the center of end-of-life decision making through storytelling. Research and Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities, 44(4), 267–279. https://doi.org/10.1177/1540796919879701

- Weber, E., & Hsee, C. (2000). Culture and individual judgment and decision making. Applied Psychology, 49(1), 32–61. https://doi.org/10.1111/1464-0597.00005

- Women’s Research Centre. (1994). Microboards review: A report to Vela Housing Society. https://www.library.ubc.ca/archives/u_arch/womens.pdf