ABSTRACT

Background: Social vulnerability refers to the ways in which an individual is at risk of being victimised. The Test of Interpersonal Competences and Personal Vulnerability [TICPV] is an Australian assessment tool designed for adults with intellectual disabilities (ID) [Wilson et al. (1996). Vulnerability to criminal exploitation: Influence of interpersonal competence differences among people with mental retardation. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 40, 8–16. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2788.1996.tb00597.x]. It aims to evaluate their social vulnerability. This study aims to conduct a preliminary cross-cultural validation of the TV-22, the French-language, enhanced and accessible version of the TICPV.

Method: Twenty-nine French-speaking adults with ID answered the TV-22. The reliability and validity of this measure were assessed.

Results: Performance on the test was shown to be internally consistent (Cronbach’s α = .89; McDonald’s Ω = .93), stable over time (rs(29) = .81, p <.01) and a valid measure of social vulnerability.

Conclusions: Results provide psychometric support for the use of the TV-22. Further research is needed to confirm these results with a larger sample.

Background

The ability to protect oneself against victimisation varies from one person or group to another and increases or decreases according to contexts and periods of life. Victimisation is a broad term that includes physical and sexual assault, financial abuse, financial exploitation, neglect, discrimination and psychological abuse, such as bullying and coercion (Fisher et al., Citation2016). The precautionary principle and the need to think about prevention and protection have led to the designation of certain groups as vulnerable (for example, the elderly, people with intellectual disabilities [ID], migrants, children, etc.). The designation of vulnerable groups is based on epidemiological and clinical information (Petitpierre, Citation2012). The risk faced by these particular groups, given some of their characteristics, is also referred to as “collective vulnerability” (Petitpierre, Citation2012). Meta-analyses from both Jones and colleagues (Citation2012) and Hughes and colleagues (Citation2012) provided valuable information on prevalence rates of violence on children and adults with ID. Jones et al. (Citation2012) reported a pooled prevalence of physical violence at 27% and 15% for sexual violence on children with ID (combined measure of violence of 21%, 1/5 children with ID). Hughes et al. (Citation2012) estimated the pooled prevalence of any (physical, sexual, or intimate partner) recent violence at 6.1% (2.5–11.1) for adults with ID.

However, the assessment of collective vulnerability gives only partial indications of the risk faced by a particular individual, and few studies have described how individuals’ characteristics can convey individual social vulnerability (Fisher et al., Citation2012). Social vulnerability refers to the ways in which an individual is at risk of being victimised. Individuals are considered to be socially vulnerable when they fail to avoid negative social relationships (Fisher et al., Citation2018).

The evaluation of social vulnerability aims to assess (a) the person's ability to progress in a given environment without taking excessive risks, and (b) his or her ability to defend him- or herself against social risks. Conclusions of the assessment of an individual’s social vulnerability influence the choices and orientations offered (academic or professional perspectives, place of residence, access to leisure, etc.) and therefore play a crucial role in the everyday life of individuals with ID.

Currently, a person’s individual social vulnerability is assessed through clinical evaluation. The caregiver evaluates the person’s vulnerability through his or her observations. Nevertheless, to have a more complete and nuanced picture of the person's strengths and limitations, it is essential to cross-reference several sources of evaluations and, whenever possible, ask the point of view of the person him- or herself. Proxies’ observations could thus be supplemented by a standardised evaluation procedure. In the last twenty-five years, some promising measures have been developed to assess the social vulnerability of individuals with ID. The Test of Interpersonal Competence and Personal Vulnerability [TICPV] (Wilson et al., Citation1996), the Social Vulnerability Scale [SVS] (Sofronoff et al., Citation2011) and the Social Vulnerability Questionnaire [SVQ] (Fisher et al., Citation2012) are three published instruments that aim to measure social vulnerability.

The SVS and SVQ are both third-party reported measures with items assessing social vulnerability. Proxies have to rate the items on a Likert scale from never to always (example of an SVS item: My child … “is overly trusting of strangers”). Initially aimed at assessing the social vulnerability of people with intellectual and developmental disabilities (Greenspan & Stone, Citation2002), the SVS has a two-factor structure (gullibility and credulity). It was recently successfully adapted and validated for several other populations. (1) Neurotypical children (Seward et al., Citation2018): among a sample of 790 parents of elementary school children (3–12 years) and another sample of 96 parents and teachers, results provided strong reliability and validity evidence (α = .86); test–retest reliability (r(73) = .74); inter-rater reliability (r(93) = .29, p = .004). (2) Children with Asperger syndrome [AS] (Sofronoff et al., Citation2011): among a sample of 133 parents of children with AS, results provided strong reliability and validity evidence (α = .94; test–retest reliability (r(25) = .85)). This study also pointed out that among other variables (anxiety, anger, behaviour problems, social skills), social vulnerability was the strongest predictor of bullying. (3) Older adults with and without cognitive impairments (Pinsker et al., Citation2006): this scale was validated among a sample of 167 undergraduate students who had to complete this informant report by rating a relative or friend aged over 50 years, whether with or without memory problems, stroke, dementia, or other neurological conditions. It had an excellent internal consistency (α = .88) and test–retest reliability (r(14) = .87).

The SVQ has been validated among a sample of 428 individuals (M = 21.38 years; SD = 8.03) with intellectual and developmental disabilities (Fisher et al., Citation2018). The SVQ is characterised by a six-factor structure (vulnerable appearance [α = .66], risk awareness [α = .81], parental independence [α = .76], social protection [α = .75], credulity [α = .82] and experience of emotional abuse [α = .91]). Confirmatory factor analysis on the SVQ delivered good to excellent fit indices (RMSEA = 0.05, TLI = 0.91, CFI = 0.92) and the differential correlation patterns among the six SVQ factors indicated good discriminant validity within the SVQ (Fisher et al., Citation2018). Lough and Fisher (Citation2016) also compared results at parent report and self-report of 102 adults (M = 27.83 years; SD = 7.96) with Williams Syndrome [WS] on the SVQ. Compared to self-report, parent’s evaluation reported a significantly higher level of social vulnerability.

The TICPV is an assessment tool designed for adults with ID (Wilson et al., Citation1996). It aims to evaluate their self-protection abilities in different types of social risks (financial exploitation: 10 items; verbal or physical assault: 2 items; sexual abuse: 5 items; inappropriate request: 3 items). The person is asked to answer 20 questions with a three-option, multiple-choice response format. The test was validated among a sample of 40 individuals with ID (Wilson et al., Citation1996). In the validation study, the test succeeds in convincingly distinguishing between individuals with ID who had suffered from victimisation (assault, sexual assault, robbery, financial exploitation, break-in) and individuals with ID who were not victims. Reliability and validity of the TICPV (α = .72) and test–retest reliability (r(20) = .72, p < .001) were good. Validation was carried out with a relatively limited number of participants (N = 40), but the follow-up studies showed good discriminatory validity with larger samples. Indeed, the TICPV has been used in several research projects with (a) 48 adults with chronic schizophrenia (Nettelbeck & Wilson, Citation1995); (b) 53 neurotypical children (Nettelbeck & Wilson, Citation1995); (c) 63 adults with ID (Nettelbeck et al., Citation2000); (d) 60 adults with ID and 60 neurotypical individuals aged more than 16 years (Murphy & O’Callaghan, Citation2004). The TICPV also inspired the development of other tools in English (Lough & Fisher, Citation2016) and has been used or is advised to be used in clinical practice (British Psychological Society, Citation2006, Citation2019).

Although these measures are promising and can be part of a clinical assessment battery in order to assess a person’s vulnerability to the risk of victimisation, none of them are available in French. There is currently no French-language tool, and no cross-cultural adaptation of a tool built in another language, available in the French-speaking countries.

The TICPV has several strengths: it is a self-reported measure developed specifically for adults with ID, and permits the study of the individual's vulnerability to several types of risk (financial exploitation, verbal and physical assault, sexual assault, inappropriate request) and several types of abuser (family, stranger, friend).

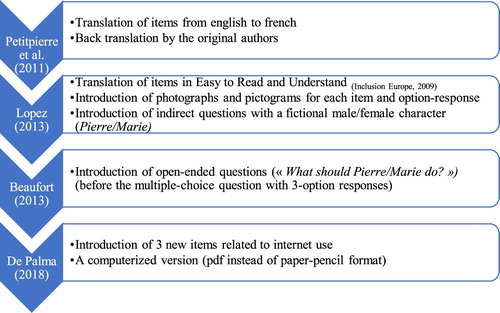

A cross-cultural adaptation of the Australian instrument TICPV was conducted for the French part of Switzerland. A cross-cultural adaptation consists of a “process that looks at both language (translation) and cultural adaptation issues in the process of preparing a questionnaire for use in another setting” (Beaton et al., Citation2001, p. 3186). The cross-cultural adaptation aims to best suit the Swiss context (e.g., change from first-person accounts to third-person accounts) and to be more actual (e.g., items involving digital risks were added). It also aims to make the items of the test more accessible according to the principle of universal design applied to assessments (Thompson et al., Citation2002). An Easy to Read and Understand language (Inclusion Europe, Citation2009) has been introduced throughout the test (e.g., illustration of the items, use of plain language). The adaptation leads to a French-language, enhanced and accessible version of the TICPV. The cross-cultural adaptation process is summarised in .

After the translation (and back translation by the original authors) of the TICPV into French (Petitpierre et al., Citation2011), three consecutive studies were conducted in the French-speaking region of Switzerland in order to proceed to the cross-cultural adaptation of the test (Beaufort, Citation2013; De Palma, Citation2018; Lopez, Citation2013). Unlike the original version of the test, which directly appeals to the participant, Lopez (Citation2013) created a female version (with the character of Marie) and a male version (with the character of Pierre). This change from first-person accounts to third-person accounts was made because it was less direct and allowed some distance between the participant and the situation (particularly for the items linked with sexual abuse) and thus allowed the participant to be freer in his/her answers. Lopez (Citation2013) also adapted the test into Easy to Read and Understand (Inclusion Europe, Citation2009). Her study, including 27 adults with ID aged 18–58 years, and 10 toddlers aged 4–8 years, confirmed that the scenario illustrations correspond well to the wording of the initial test, both for the main vignettes and for the response vignettes. When the identification of the illustrated scenario was insufficient (<70% of participants), the material was reworked.

Beaufort (Citation2013) verified the accuracy of the multiple-choice answers. She introduced open-ended questions (i.e., “What should Pierre/Marie do?”) to ensure that the proposed choices were among the solutions spontaneously mentioned by respondents. She was able to confirm this assumption by analysing the responses given by 20 young people with ID, aged 17–20 years, and by 20 neurotypical persons matched on chronological age. Beaufort’s analysis of the answers to open-ended questions also underpinned the value of such questions: most of the answers reflected the spontaneous reasoning of the respondents and conveyed very interesting clinical information, for example on the clues used to support the reasoning and/or on the finesse of the reasoning itself.

As Internet access has become more widespread, people with ID may also be exposed to risks related to Internet use (Chadwick et al., Citation2013). This raises the need for items portraying risk situations related to Internet use. De Palma (Citation2018) generated three items (into Easy to Read and Understand [Inclusion Europe, Citation2009]) on this topic from situations inspired by news stories and scientific literature. These items refer to the risk of being assaulted verbally in an online discussion, of transmitting personal or private data and finally of being sexually solicited on the Internet. Eight academic participants in the field of special education (six master’s students, one PhD student and one professor at the University of Fribourg) assessed their relevance, their representativeness and the accessibility of the wording for the public with an ID. Four people involved professionally or personally in the field of ID (a person in charge of an institution for adults with a mild to moderate ID; the mother of an adult person with an ID; a specialised educator; a man with an ID) verified that the selected illustrations do not offend sensitivity. Finally, the paper-pencil format of the test was updated through a computerised version (pdf) in order to increase the attractiveness of the test, as well as to be able to disseminate the test at a lower cost afterwards (De Palma, Citation2018).

In short, direct questions were replaced by indirect questions where the respondent is asked to advise a fictional character. The content of the item was illustrated with photographs (Lopez, Citation2013). Open-ended questions have been added to the three-option responses to multiple-choice questions (Beaufort, Citation2013). Items linked with the use of the Internet were added (De Palma, Citation2018). These several adaptations have led to a 23-item version submitted to the validation process.

This study aimed to conduct a preliminary cross-cultural validation of the French-language, enhanced and accessible version of the TICPV.

Method

Ethical approval for the study was obtained from Swissethics (Swiss Ethics Committee on research involving humans, N°2016-01480).

Sample

Twenty-nine French-speaking adults with ID were interviewed and answered the TICPV French version two times (with two to four weeks in between). Fifty-two percent of the sample was female. The mean age of the participants was 29.07 (SD = 13).

Recruitment

The study was conducted in the French-speaking part of Switzerland between March 2016 and September 2018. Potential participants were identified by local leaders of four social institutions for adults with ID. Local leaders were asked to respect the following inclusion criteria: French-speaking adults (i.e., 18 years and older) with mild to moderate ID, able to have a short conversation. According to the procedure proposed by Petitpierre et al. (Citation2013), potential participants and their legal representatives were invited to an informational meeting about the study. Informed consent of both the participants and their legal representatives was required in order to take part in the study.

Measures

Social vulnerability measure: characteristics of the French version of the TICPV

The TICPV French version consists of 23 questions, with an open-ended question followed by a three-option, multiple-choice question. There is a male and a female version. In the male version, the participant is asked to counsel Pierre, and in the female version, the participant is asked to counsel Marie. Each of the 23 questions describes an interaction by Pierre/Marie with a stranger (11 items), an acquaintance/friend (10 items) or a family member (2 items). Four risk dimensions are assessed: financial exploitation (9 items), verbal or physical assault (4 items), sexual abuse (6 items), inappropriate request (4 items). In each situation, an inappropriate request or action is made or carried out by the person against Pierre/Marie. After the presentation of the situation, the participant is asked an open-ended question (Que doit faire Pierre? [What should Pierre do?]). Afterwards, the participant is required to choose between three options (a, b, c) (). As in the original version, the incorrect responses are either overly helpful or aggressive, while the “most cautious response” terminates the interaction in a way that minimises harm and hostility. The position (a, b or c) of the “most cautious response” was randomised among the three options for each situation. Only the “most cautious” responses are considered as “correct” and scored 1. Incorrect responses are scored 0.

Convergent and control measures

A convergent measure of vulnerability for victimisation was used. All items from the last Adaptative Behaviour Assessment System [ABAS-3] (Harrison & Oakland, Citation2015) relating to social vulnerability were collected and translated into French. This third-party report consisted of 14 items rating on a 4-point scale of the extent of the social vulnerability of participants (example of item: “distinguishes between truthful and exaggerated claims by friends, advertisers or others”. Rated from “never” [0] to “always” [3]). The highest score possible was 42 points, which would express a low social vulnerability ().

Table 1. Convergent and control measure scores (N = 29).

The Supports Intensity Scale, French version [SIS-F] (Thompson et al., Citation2007) was used as a control measure. The SIS-F is a multidimensional scale that aims to assess the pattern and intensity of an individual's support needs. The scale consists of a main section, followed by two additional sections. The first section is the scale of support needs. It is composed of six domains (personal, work-related, social activities, community living, lifelong learning, health and safety). Scores in section 1 are reported in the Supports Needs Index, which is divided into four levels: Level I (scores 84 or fewer points, mild level of support needed), Level II (scores between 85 and 99, moderate level of support needed), Level III (scores between 100 and 115, substantial level of support needed), Level IV (scores higher than 116, pervasive level of support needed). The two additional sections focus respectively on (a) protection and advocacy and (b) exceptional medical and behavioural support needs.

The Raven’s Coloured Progressive Matrices Test ([RCPM], Raven, Citation2000) was used to characterise the sample. This test measures the individual’s non-verbal, abstract and cognitive functioning.

Procedure

A research team member with a master's degree in special education or psychology interviewed each participant individually, in a room provided by the social institution where the participant was working or living. During the first meeting, Raven’s Coloured Progressive Matrices Test was conducted. After a short break, the TICPV French version was completed. Female participants received the female version and males received the male version. The research team member read for each participant what appeared on the screen of the computer (i.e., the instruction and the items of the TICPV) and wrote down the participant’s answer. The first meeting lasted approximately 1 h 30 min. Then a retest on the TICPV French version, with the same assessor, was carried out 2–4 weeks later. This time frame was chosen to reduce the bias of recalling previous answers. Once the TICPV French version was administered (test and retest), the ABAS-3 short-report and the SIS-F were completed by the caregivers of the participants in accordance with standard procedures (person assessed in daily setting, in real time, by a rater – caregiver – who knows him/her well). Information was sent back to the research team.

All interviews were recorded using a voice recorder and then fully transcribed in order to proceed to the analysis. As our aim was to do a preliminary validation of the psychometric properties of the TICPV French version, the analysis was carried out on the quantitative data resulting from the three-option, multiple-choice response format and not on the answers to the open-ended questions, which will be presented in another article.

Analysis

SPSS-25 was used to carry out the main data analysis. Given that none of the outcome variables were normally distributed, Spearman’s coefficient was used to calculate the correlations (Field, Citation2014). Two members of the research team reviewed 100% of the participants’ answers (to the three-option, multiple-choice questions) in order to compute the inter-reliability analysis. A test-retest and inter-rater reliability analysis was conducted using Svensson’s rank-based statistical method for disagreement analysis (Svensson, Citation2001). McDonald’s omega and Cronbach’s alpha were calculated with R Studio (Dunn et al., Citation2014; Peters, Citation2014).

Results

All the analyses were calculated on the full sample of 29. Regarding the SIS-F results, the mean score of the Supports Needs Index was 75.66 (SD = 7.513). Most participants had a level of support needs corresponding to Level I (i.e., scores <84). Of the participants, 4 out of 29 had a level of support needs corresponding to Level II (i.e., scores on SIS-F between 85 and 99).

One item (No. 23 “if someone on the Internet always says mean words to Pierre/Marie, what should Pierre/Marie do?”) with no variation in response (i.e., all participants always chose the “most cautious answer” at the test and the retest) was dropped. This item was one of the three new items added by De Palma (Citation2018). It was the last item of the test and referred to online bullying on the Internet. The removal of this item resulted in a 22-item version “TV-22” on which the subsequent analyses were conducted. Mean score on TV-22 was 17.37 (SD = 4.97) points. Maximum score was 22 points. A quarter of the respondents chose a not cautious answer for items No. 12 (financial exploitation by a friend), No. 19 (financial exploitation by a friend) and No. 4 (sexual abuse by a stranger). Scores on TV-22 were not correlated to participants’ gender or age. Neither were they correlated to the scores of the short ABAS-3 report (α = .99; Ω = .94). In contrast, scores on TV-22 were correlated to the RCPM’s score (rs = .47, p < .01) and to the Supports Needs Index (rs = −.52, p < .01). Among the SIS-F dimensions, two were more specifically correlated with the TV-22 global score: Community Living (rs = −.44, p < .05) and Health and Safety (rs = −.40, p < .05).

As TV-22 is multidimensional, the internal consistency reliability of the global score and the four risk dimensions (financial exploitation, verbal or physical assault, sexual abuse, inappropriate request) were both evaluated with Cronbach’s alpha and McDonald’s omega (McDonald, Citation1981). According to DeVellis (Citation2017) cut-offs, internal consistency of the global score was very good (α = .89, Ω = .93). The Cronbach’s alpha and McDonald’s omega of the dimension concerning financial exploitation (items No. 1–(No. 6Footnote1)–No. 12–No. 13–No. 14–No. 16–No. 18–No. 19–No. 20) were very good (α = .75, Ω = .86). The sexual abuse dimension (items No. 4–No. 7–No. 8–No. 11–No. 17–No. 22) showed a “respectable” (i.e., between .70 and .80) to “high” internal consistency (α = .79, Ω = .89), while the dimension relating to inappropriate requests (items No. 5–No. 9–No. 10–No. 21) reached the “minimally acceptable” score (α= .64, Ω = .83). Given the small number of items of the verbal (item No. 2) and physical assault dimension (items No. 3–No. 15), internal consistency of these dimensions was not computed.

Since reliability means a high level of agreement in test–retest and inter-rater assessments, the percentage of agreement (PA) was calculated (Svensson, Citation2012). Svensson’s method was used to calculate the percentage of agreement at T0 between two inter-raters. Raters agreed in more than 90% of the assessments (PA range = 93% to 100%). Cohen’s k confirms the strong inter-rater agreement evaluation (Lund Research Ltd, Citation2018). Cohen’s k results are shown in .

Table 2. Inter-rater reliability (N = 29).

Test–retest results were stable over time (rs(29) = .81, p < .01). Except for item No. 16 (PA = 69%), PA measures for all items range from 72 to 100%, which means that most participants were stable in their test–retest assessments. Analysis shows a good test–retest reliability for all items except for item No. 16 (Marie/Pierre gets home from work and finds someone (s)he doesn’t know in her/his house). Nevertheless, the PA of item No. 16 is close to the cut-off of satisfactory level (i.e., >70% according to Kazdin, Citation1977). See for detailed results.

Table 3. Test–retest reliability.

Discussion

The TV-22, which was adapted from the Test of Interpersonal Competences and Personal Vulnerability (TICPV), is designed to assess the social vulnerability of adults with ID. The current study examined the psychometric properties of the TV-22. The findings provide preliminary support for the utilisation of the test, as the test demonstrates very good internal consistency and good test–retest and inter-rater reliability. The main findings of this study will be discussed in further details: results suggest that social vulnerability is not linked with gender or age but to the level of support needed and to IQ level; they highlight discrepancies between self-report (TV-22) and third-party report of social vulnerability (short ABAS-3); finally, among the 22 items of the test, three were more difficult for the participants, even if the quite high mean global score on the TV-22 suggest a ceiling effect.

Link between social vulnerability and need for support

Results showed that scores on TV-22 were negatively correlated to the need for support in daily activities. In other words, it means that the less an individual needs support in the context of community living and for his or her health and safety, the less (s)he is socially vulnerable. These results are similar to those of Lough and Fisher (Citation2016) who explored the social vulnerability of 102 adults with Williams Syndrome, through both self-report and parent report. Those who reported greater functional independence, as measured with the Activities of Daily Living [ADL] (Seltzer & Li, Citation1996) also showed less social vulnerability (as measured with the SVQ). More generally, individuals with ID with a higher degree of independence seem to report higher social participation (i.e., interpersonal relations, social inclusion, rights) than their more dependent peers (Alonso-Sardón et al., Citation2019; Simoes et al., Citation2016). Social skills of individuals with ID may thus vary not only in relation to the severity and etiology of the ID but also in relation to the opportunities for learning they are offered (Sigafoos et al., Citation2017). Adults with ID may be less independent because they are offered fewer opportunities for making choices (Simoes et al., Citation2016). Individuals who need less support may often also be those who attend more diverse and open environments and can benefit from a richer relational environment, offering more opportunities and more examples that inspire learning and the development of a wide range of valuable and diverse solutions. This could explain why the individual’s level of independence (and the opportunities of rich self-experiences) probably plays an important role in preventing social vulnerability.

Link between social vulnerability and fluid intelligence

Scores on TV-22 are correlated to the participant’s non-verbal, abstract and cognitive functioning (as measured with RPCM). These results were similar to those of the original instrument, where a significant correlation was observed between scores on the TICPV and IQ – as measured with TONI-2 (Brown et al., Citation1990) (TONI-2, n = 40, rs = .40, p < .05). This outcome suggests a moderate association between ability to protect oneself and fluid intelligence. This relation is theoretically consistent as the RPCM score reflects fluid intellligence, which is associated with new problem resolution abilities, in particular, relational reasoning (i.e., the ability to be creative, identify and consider relationships between multiple mental options) (Crone et al., Citation2009; Krawczyk, Citation2012). Intellectual disability is primarily “a disorder of reasoning and judgement” (Greenspan & Woods, Citation2014). These specific results can explain the difference with the results of Lough and Fisher (Citation2016) who found no correlation between the SVQ total score (or sub-scores) and IQ measured with the Kaufman Brief Intelligence Test 2nd ed. (KBIT-2; Kaufman & Kaufman, Citation2004). This difference can be explained by the fact that KBIT-2 is a composite test designed for screening and assessing several cognitive sub-dimensions (receptive vocabulary, verbal reasoning, matrices, including general knowledge) and not intended for the in-depth assessment of fluid intelligence. In view of this statement, further research is needed to explore in a thorough way the role of cognitive sub-skills in risk (un)awareness and social victimisation (Greenspan et al., Citation2011).

Link between social vulnerability (self-report) and adaptive behaviour (third-party report)

The results show no correlation between social vulnerability (self-report with TV-22) and the 14 items from the adaptive behaviour assessment related to social vulnerability (caregiver report with short ABAS-3). The following explanations can be put forward to account for this outcome:

Since, in the present study, the adaptive behaviour was measured with a non-validated translated version of ABAS-3, we cannot exclude a measurement problem due to the quality of the translation. As the same caregiver responded both to ABAS and SIS-F, we cannot suspect a problem with the informant, but rather with the rigour of the information-gathering tool. The rigour of the measures concerning adaptive behaviour is moreover a prevailing topic (Salekin et al., Citation2018). It should also be noted that the discrepancy between self-report (TV-22) and caregiver (short version of ABAS-3) on social vulnerability looks very much like the findings of Lough and Fisher (Citation2016). In their study, self-report of adults with Williams Syndrome and parent reports on social vulnerability were significantly different. An explanation for these differences may lie in the type of measurement. Dunning and colleagues (Citation2004) reviewed empirical findings on self-assessment of neurotypical persons and found that the correlation between self-ratings of skill and actual performance in many domains (e.g., health, education, workplace) is moderate to meagre. Informant report predicts a person’s behaviour more accurately than that person’s self-prediction (Balsis et al., Citation2014; Dunning et al., Citation2004; Galione & Oltmanns, Citation2013). Overall people seem to commonly overestimate the likelihood that they will engage in desirable behaviours (Dunning et al., Citation2004). These findings underpin the importance of crossing the sources of evaluations. De los Reyes and colleagues (Citation2019) argue for the value of a new assessment paradigm termed intersubjectivity, which considers that “each method (e.g., subjective, laboratory observation, objective) yields useful information about the experiences and/or contexts in which one observes displays of the phenomenon under study”. Rather than embracing the merits of some assessment forms and shunning the use of others, findings from their meta-analysis emphasise the importance of examining sources collectively. Multi-informant and multi-method approaches are critical to understand a phenomenon. Points of convergence and divergence should not be considered as noise that disturbs the understanding but might reflect contextual variations in behaviour and /or in social environment, as they might index meaningful information about the psychological phenomena under investigation (De Los Reyes et al., Citation2019). The fact that the evaluation of the social vulnerability of the participant by the caregiver does not match the self-report of social vulnerability underlines the need for further theory and research on this intersubjectivity, its meaning and its implication for practice.

Possible ceiling effect

The mean global score (17.37/ 22 points, SD = 4.97) on the TV-22 may suggest a ceiling effect. Such an effect was not observed in the original instrument. For ethical reasons, this study only included participants who had not been abused in the past. If we take this into account, the results are not so far from those of the original study of Wilson et al. (Citation1996), where the average global score on TICPV was 15.00 (SD = 2.23) on 20 points for adults with ID known as not being victims of abuse, but 12.75 (SD = 4.05) on 20 points for people known as having been victimised in the last 10–12 months. However, the difference can also be explained in several other ways: the high scores on TV-22 could be related to the changes introduced, e.g., to the fact that the items were presented in the Easy to Read and Understand Format; or to the fact that participants had to counsel Pierre/Marie and not speak for themselves. The change from first-person account to third-person account may have positively affected their answers by introducing a kind of conceptual step back (i.e., the person knows what is the most cautious behaviour for Pierre/Marie, but she/he would not act in this way). Another explanation could be linked to a possible rise in social vulnerability scores over generations, resulting in the population’s gains across time (i.e., “Flynn Effect” for IQ, Flynn, Citation1984), as it has been shown for fluid intelligence (Wongupparaj et al., Citation2015) to which it correlates. Some studies hypothesise that the Flynn Effect is not limited to intelligence tests but may be present across cognitive domains (Trahan et al., Citation2014).

Heightened social vulnerability

The three most difficult items for all respondents were items No. 12 and No. 19, which both imply financial exploitation by a friend, and item No. 4 (sexual abuse by a stranger). Regarding item No. 4 (“Marie/Pierre is in the toilet at work. Someone comes in and says he want to touch her/his private parts”), while 17 persons answered with the most cautious option (option a, “say that s/he doesn’t like people doing that”), nine persons chose to avoid the situation (option c, “don’t go to the toilet again”) and three persons chose option b (“let them do it because they might get angry”). The fact that one third of the sample chose not to go to the toilet any more provides a precious insight into the difficulty of some participants to assess the adequacy – in the long term – of the solution. The response is indeed not a viable option, because no-one can do without going to the bathroom for long. Thirteen persons at item No. 12 (“Marie/Pierre receives a smartphone for Christmas and a friend asks her/him to give it to her.”), did not choose the “most cautious answer” (option b, “let her listen to music with it but don’t give it to her”). Twelve persons chose rather option c, “give her money to buy her own”, and one person chose option a (“give it to her because it’s good to share”). At item No. 19 (“Marie/Pierre put some money in a piggy bank at home and a friend takes it.”), rather than choose option b (“tell his/her friend s/he knows she took it”), 12 persons preferred option c (“go to the friend’s house and take it from her”), while 1 person chose to forget about it (option a). These results may suggest a higher social vulnerability when there is a friendship relation between the victim and the offender, particularly with regard to financial exploitation. These results are similar to results on the SVQ, where 43 parents (out of 102) of adults with Williams Syndrome, when they were asked to give an example of their child’s social victimisation during the last year, provided an example of financial exploitation (e.g., “He has become friends with customers of his store. One of these individuals convinced him to give her money because she was going to lose her house. He used his debit card and gave her $300.”, from Lough & Fisher, Citation2016). More generally, results on TV-22 tend to confirm the risk of financial exploitation for individuals with ID, a risk that has already been identified as a common form of victimisation for this group (Fisher et al., Citation2012; Greenspan et al., Citation2001; Lough & Fisher, Citation2016; Nettelbeck & Wilson, Citation2001).

The fact that participants struggled with items involving friendships also corroborates findings of qualitative researches investigating friendships of persons with ID (Bane et al., Citation2012). In a participatory research involving almost one hundred adults with ID, Bane and colleagues found that education on friendships and relationships would help adults with ID to have and keep their social relations. Results on the TV-22 and participants’ choice of answer underpins the need for more research on friendships process among individuals with ID, in particular their ability to manage symmetrical relations with peers and self-protection. Such results would allow professionals to better support them in practice, for example through peer mentoring programs aiming at training social skills in more authentic settings (Athamanah et al., Citation2019).

Limitations, synthesis and implications

Despite a small sample size, results provide psychometric support for the use of TV-22. Nevertheless, a factor analysis of the TV-22 is needed to confirm these results. Future work should consist of a larger random sample in order to confirm these preliminary results.

Other situations of possible victimisation, which would be important to assess nowadays as well (for example, use of social media, sexting, etc.) were not created and the dimensions evaluated were not equal in terms of number of items. Consequently, research could improve this by balancing the explored dimensions (financial exploitation, sexual assault, verbal or physical assault, inappropriate request) and updating them with current social risks.

The cross-cultural adaptation of the TICPV led to several changes in the test, although the French version aimed to stay as close as possible to the original Australian version.

The high scores on the TV-22 and the fact that these were not correlated to the third-party reports underpins that the test is more accurate to highlight learned knowledge or social rules (e.g., “you should not give money to someone you don’t know”) rather than personal vulnerability in real life. Thus, this also underlines the need to cross-reference the sources and method of measurement. Further research should examine social vulnerability reports through the lens of intersubjectivity in order to inform an understanding of the intersection between vulnerability traits and the social contexts eliciting these traits. As a self-report measure, the TV-22 could be used with the SVQ (Fisher et al., Citation2018), which is a third-party report measure. Together, these evaluations would lead to a fuller picture of the person’s strengths and limitations in social risky situations.

To summarise, the results highlight the importance of teaching independence in daily activities, but also of providing the necessary social support and education to enable adults with ID to avoid victimisation. Findings of the TV-22 could thus help clinicians to provide better support of adults with ID in their daily life. Clinicians could use the TV-22 to assess the progress of the people with whom they work, either as part of an annual assessment or before/after attending courses on socialisation or abuse prevention. TV-22 could also be used in further research in pre-testing and post-testing to assess the effectiveness of an abuse prevention intervention (e.g., the program ESCAPE-NOW, Khemka & Hickson, Citation2015) or a program aiming at training social skills (e.g., the Friendships and Dating Program, Ward et al., Citation2013).

Finally, beyond the global score on the test, it seems that the way the person thinks in these situations is a key to assess a person’s social vulnerability. We are currently conducting a study that aims to analyse this framework and investigate the answers.

As Atkinson and Ward (Citation2012, p. 307) wrote:

we are beginning to understand the severity and intricacies of interpersonal violence for people with ID/DD. A shared awareness of the problem will help to better understand how to best measure the problem and to develop strategies to prevent interpersonal violence in the lives of individuals with ID/DD. There is a paucity of tools to assess these issues.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the participants and the institutions Geneva University Hospitals, The Perce-Neige Foundation, The Valaisanne Foundation for Mentally Handicapped People (FOVAHM), The Arche Switzerland, and the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF). There were no imposed restrictions on free access to or publication of the research data. All authors have contributed to, seen, and approved of the manuscript and agree to the order of authors as listed.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Item 6 was excluded from the internal consistency reliability analysis because of missing data.

References

- Alonso-Sardón, M., Iglesias-de-Sena, H., Fernández-Martín, L. C., & Miron-Canelo, J. A. (2019). Do health and social support and personal autonomy have an influence on the health-related quality of life of individuals with intellectual disability? BMC Health Research Services, 19, 63. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-018-3856-5

- Athamanah, L. S., Josol, C. K., Ayeh, D., Fisher, M. H., & Sung, C. (2019). Understanding friendships and promoting friendship development through peer mentoring for individuals with and without intellectual and developmental disabilities. In R. M. Hodapp & J. D. Fidler (Eds.), International Review of research in developmental disabilities (Vol. 57, pp. 1–48). Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.irrdd.2019.06.009

- Atkinson, J. P., & Ward, K. M. (2012). The development of an assessment of interpersonal violence for individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Sexuality and Disability, 30(3), 301–309. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11195-012-9275-3

- Balsis, S., Cooper, L. D., & Oltmanns, T. F. (2014). Are informant reports of personality more internally consistent than self reports of personality? Assessment, 22, 399–404. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073191114556100

- Bane, G., Dooher, M., Flaherty, J., Mahon, A., Donagh, P. M., Wolfe, M., & Shannon, S. (2012). Relationships of people with learning disabilities in Ireland. British Journal of Learning Disabilities, 40, 109–122. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-3156.2012.00741.x

- Beaton, D., Bombardier, C., Guillemin, F., & Ferraz, M. (2001). Guidelines for the process of cross-cultural adaption of self-report measures. Spine, 25, 3186–3191. https://doi.org/10.1097/00007632-200012150-00014

- Beaufort, N. (2013). Analyse du traitement de l’information sociale permettant la prise de décision efficace face à une situation à risques d’abus [Analysis of the processing of social information to enable effective decision making in a situation at risk of abuse] [Unpublished master’s thesis]. University of Liège.

- British Psychological Society. (2006). Assessment of Capacity in adults: Interim Guidance for Psychologists. The British Psychological Society.

- British Psychological Society. (2019). Consent to sexual relations. Professional practice Board and mental Capacity Advisory group.

- Brown, L., Sherbenou, R. J., & Johensen, S. K. (1990). Test of Non-verbal intelligence: A language-free measure of cognitive ability. Pro-Ed Inc.

- Chadwick, D., Wesson, C., & Fullwood, C. (2013). Internet access by people with intellectual disabilities: Inequalities and opportunities. Future Internet, 5, 376–397. https://doi.org/10.3390/fi5030376

- Crone, E. A., Wendelken, C., van Leijenhorst, L., Honomichl, R. D., Christoff, K., & Bunge, S. A. (2009). Neurocognitive development of relational reasoning. Developmental Science, 12, 55–66. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-7687.2008.00743.x

- De Los Reyes, A., Lerner, D. M., Keely, M. L., Weber, R. J., Drabick, D. A. G., Rabinowitz, J., & Goodman, L. K. (2019). Improving interpretability of subjective assessments about psychological phenomena: A review and cross-cultural meta-analysis. Review of General Psychology, 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1177/1089268019837645

- De Palma, N. (2018). TCIVP – FEAI. Test de Compétences Interpersonnelles et de Vulnérabilité Personnelle – version Française, Enrichie, Accessibilisée et Informatisée [TCIVP – FEAI. Test of interpersonal competences and personal vulnerability – French, enriched, accessible and computerized version] [Unpublished master’s thesis]. University of Fribourg.

- DeVellis, R. F. (2017). Scale development: Theory and applications (4th ed.). SAGE.

- Dunn, T. J., Baguley, T., & Brunsden, V. (2014). From alpha to omega: A practical solution to the pervasive problem of internal consistency estimation. British Journal of Psychology, 105(3), 399–412. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjop.12046

- Dunning, D., Heath, C., & Suls, J. M. (2004). Flawed self-assessment: Implications for health, education, and the workplace. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 5, 69–106. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1529-1006.2004.00018.x

- Field, A. (2014). Discovering statistics using IBM SPSS statistics (4th ed.). SAGE.

- Fisher, M. H., Corr, C., & Morin, L. (2016). Victimization of individuals With intellectual and developmental disabilities across the Lifespan. In R. M. Hodapp & J. D. Fidler (Eds.), International review of research in developmental disabilities (Vol. 51, pp. 233–280). Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.irrdd.2016.08.001

- Fisher, M. H., Moskowitz, A. L., & Hodapp, R. M. (2012). Vulnerability and experiences related to social victimization among individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Journal of Mental Health Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 5(1), 32–48. https://doi.org/10.1080/19315864.2011.592239

- Fisher, M. H., Shivers, C. M., & Josol, C. K. (2018). Psychometric properties and utility of the social vulnerability questionnaire for individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-018-3636-4

- Flynn, J. R. (1984). The mean IQ of Americans: Massive gains 1932 to 1978. Psychological Bulletin, 95(1), 29–51. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.95.1.29

- Galione, J. N., & Oltmanns, T. F. (2013). Identifying personality pathology associated with major depressive episodes: Incremental validity of informant reports. Journal of Personality Assessment, 95, 625–632. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223891.2013.825624

- Greenspan, S., Loughlin, G., & Black, R. S. (2001). Credulity and gullibility in people with developmental disorders: A framework for future research. In L. M. Glidden (Ed.), International review of research in mental retardation (Vol. 24, pp. 101–135). Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0074-7750(01)80007-0

- Greenspan, S., & Stone, V. (2002). Gullibility Rating Scale [Unpublished manuscript].

- Greenspan, S., Switzky, H. N., & Woods, G. W. (2011). Intelligence involves risk-awareness and intellectual disability involves risk-unawareness: Implication of a theory of common sense. Journal of Intellectual & Developmental Disability, 36(4), 246–257. https://doi.org/10.3109/13668250.2011.626759

- Greenspan, S., & Woods, G. W. (2014). Intellectual disability as a disorder of reasoning and judgement: The gradual move away from intelligence quotient-ceilings. Current Opinion Psychiatry, 27(2), 110–116. https://doi.org/10.1097/YCO.0000000000000037

- Harrison, P., & Oakland, T. (2015). ABAS-3 (3rd ed.). Western Psychological Services.

- Hughes, K., Bellis, M. A., Jones, L., Wood, S., Bates, G., Eckley, L., McCoy, E., Mikton, C., Shakespeare, T., & Officer, A. (2012). Prevalence and risk of violence against adults with disabilities: A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. The Lancet, 379(9826), 1621–1629. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61851-5

- Inclusion Europe. (2009). L’information pour tous, règles européennes pour une information facile à lire et à comprendre [Information for all, European standards for making information easy to read and understand]. https://easy-to-read.eu/fr/european-standards/

- Jones, L., Bellis, M. A., Wood, S., Hughes, K., McCoy, E., Eckley, L., Bates, G., Mikton, C., Shakespeare, T., & Officer, A. (2012). Prevalence and risk of violence against children with disabilities: A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. The Lancet, 380(9845), 899–907. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60692-8

- Kaufman, A. S., & Kaufman, N. L. (2004). Kaufman Brief intelligence test (2nd ed.). Pearson.

- Kazdin, A. E. (1977). Artifact, bias, and complexity of assessment: The ABCs of reliability. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 10(1), 141–150. https://doi.org/10.1901/jaba.1977.10-141

- Khemka, I., & Hickson, L. (2015). ESCAPE-NOW: An effective strategy-based curriculum for abuse prevention and empowerment for individuals with developmental disabilities – NOW. Teachers College, Columbia University.

- Krawczyk, D. C. (2012). The cognition and neuroscience of relational reasoning. Brain Research, 1428, 13–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brainres.2010.11.080

- Lopez, K. (2013). Adaptation du Test de compétence interpersonnelle et de vulnérabilité personnelle (Wilson, Seaman, & Nettelbeck, 1996/2001) [Adaptation of the Interpersonal Competences and Personal Vulnerability Test (Wilson, Seaman, & Nettelbeck, 1996/2001)] [Master’s thesis, University of Geneva]. Archives ouvertes UNIGE. https://archive-ouverte.unige.ch/unige:30678

- Lough, E., & Fisher, M. H. (2016). Parent and self-report ratings on the Perceived levels of social vulnerability of adults with Williams Syndrome. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 46(11), 3424–3433. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-016-2885-3

- Lund Research Ltd. (2018). Cohen’s kappa using SPSS statistics. Laerd Statistics. https://statistics.laerd.com/spss-tutorials/cohens-kappa-in-spss-statistics.php

- McDonald, R. P. (1981). The dimensionality of tests and items. British Journal of Mathematical and Statistical Psychology, 34(1), 100–117. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8317.1981.tb00621.x

- Murphy, G. H., & O’Callaghan, A. C. (2004). Capacity of adults with intellectual disabilities to consent to sexual relationships. Psychological Medicine, 34, 1347–1357. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291704001941

- Nettelbeck, T., & Wilson, C. (1995). Criminal victimisation: The influence of interpersonal competence on personal vulnerability. https://www.criminologyresearchcouncil.gov.au/reports/16-94-5.pdf

- Nettelbeck, T., & Wilson, C. (2001). Criminal victimization of persons with mental retardation: The influence of interpersonal competence on risk. In L. M. Glidden (Ed.), International review of research in mental retardation (Vol. 24, pp. 101–135). Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0074-7750(01)80008-2

- Nettelbeck, T., Wilson, C., Potter, R., & Perry, C. (2000). The influence of interpersonal competence on personal vulnerability of persons with mental retardation. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 15, 46–62. https://doi.org/10.1177/088626000015001004

- Peters, G. Y. (2014). The alpha and the omega of scale reliability and validity: Why and how to abandon Cronbach’s alpha and the route towards more comprehensive assessment of scale quality. The European Health Psychologist, 16(2), 59–69. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/h47fv

- Petitpierre, G. (2012). Handicap et vulnérabilité aux abus. Cadre conceptuel et opérationnel [Disability and vulnerability to abuse. Conceptual and operational framework]. Revue Suisse de Pédagogie Spécialisée, 3(7), 9–15.

- Petitpierre, G., Gremaud, G., Veyre, A., Bruni, I., & Diacquenod, C. (2013). Aller au-delà de l’alibi. Consentement à la recherche chez les personnes présentant une déficience intellectuelle [Go beyond the alibi. Consent to the research in individuals with intellectual disabilities. Discussion of ethical cases in ethnological research]. Société Suisse D’Ethnologie, 10. http://www.seg-sse.ch/pdf/2013-03-27_Petitpierre.pdf

- Petitpierre, G., Noir, S., & Jungo, M. (2011). Test de compétence interpersonnelle et de vulnérabilité personnelle (TCIVP) [Test of interpersonal competences and personal vulnerability] [Unpublished manuscript]. University of Geneva.

- Pinsker, D. M., Stone, V., Pachana, N., & Greenspan, S. (2006). Social vulnerability scale for older adults: Validation study. Clinical Psychologist, 10(3), 109–119. https://doi.org/10.1080/13284200600939918

- Raven, J. (2000). The Raven’s progressive matrices: Change and stability over culture and time. Cognitive Psychology, 41(1), 1–48. https://doi.org/10.1006/cogp.1999.0735

- Salekin, K. L., Neal, T. M. S., & Hedge, K. A. (2018). Validity, inter-rater reliability, and measures of adaptive behavior: Concerns regarding the probative versus prejudicial value. Psychology, Public Policy, and Law, 24, 24–35. https://doi.org/10.1037/law0000150

- Seltzer, M. M., & Li, L. W. (1996). The transitions of caregiving: Subjective and objective definitions. The Gerontologist, 36(5), 614–626. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/36.5.614

- Seward, R. J., Bayliss, D. M., & Ohan, J. L. (2018). The children’s social vulnerability questionnaire (CSVQ): validation, relationship with psychosocial functioning, and age-related differences. International Journal of Clinical and Health Psychology, 18(2), 179–188. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijchp.2018.02.001

- Sigafoos, J., Lancioni, G. E., Singh, N. N., & O’Reilly, M. F. (2017). Intellectual disability and social skills. In J. L. Matson (Ed.), Handbook of social behavior and skills in children (pp. 249–271). Springer.

- Simoes, C., Santos, S., Biscaia, R., & Thompson, J. R. (2016). Understanding the relationship between quality of life, adaptive behavior and support needs. Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities, 28, 849–870. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10882-016-9514-0

- Sofronoff, K., Dark, E., & Stone, V. (2011). Social vulnerability and bullying in children with Asperger syndrome. Autism, 15(3), 355–372. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361310365070

- Svensson, E. (2001). Guidelines to statistical evaluation of data from rating scales and questionnaires. Journal of Rehabilitation Medicine, 33(1), 47–48. https://doi.org/10.1080/165019701300006542

- Svensson, E. (2012). Different ranking approaches defining association and agreement measures of paired ordinal data. Statistics in Medicine, 31(26), 3104–3117. https://doi.org/10.1002/sim.5382

- Thompson, J. R., Bryant, B. R., Campbell, E. M., Craig, E. M., Hugues, C. M., Rotholz, D. A., Schalock, R. L., Silverman, W., Tassé, M. J., & Wehmeyer, M. L. (2007). L’échelle d’intensité de soutien: Manuel de l’utilisateur [Support intensity scale: User manual]. AAIDD.

- Thompson, S., Johnstone, C. J., & Thurlow, M. L. (2002). Universal design applied to large scale assessments (Synthesis report 44). University of Minnesota, National Center on Educational Outcomes. https://nceo.umn.edu/docs/OnlinePubs/Synth44.pdf

- Trahan, L. H., Stuebing, K. K., Fletcher, J. M., & Hiscock, M. (2014). The Flynn effect: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 140(5), 1332–1360. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0037173

- Ward, K. M., Atkinson, J. P., Smith, C. A., & Windsor, R. (2013). A friendships and dating program for adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities: A formative evaluation. Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 51, 22–32. https://doi.org/10.1352/1934-9556-51.01.022. doi: 10.1352/1934-9556-51.01.022

- Wilson, C., Seaman, L., & Nettelbeck, T. (1996). Vulnerability to criminal exploitation: Influence of interpersonal competence differences among people with mental retardation. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 40, 8–16. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2788.1996.tb00597.x

- Wongupparaj, P., Kumari, V., & Morris, R. G. (2015). A cross-Temporal meta-analysis of Raven's Progressive Matrices: Age groups and developing versus developed countries. Intelligence, 49, 1–9. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.intell.2014.11.008