ABSTRACT

Background: “Convivial encounter” provides a new lens for understanding social inclusion of people with intellectual disabilities, characterised by shared activity and friendly interactions with strangers without intellectual disabilities. Places, props and support practices facilitate incidental convivial encounters. This study explored processes for deliberately creating opportunities for such encounters.

Methods: A case study design used mixed methods to collect data from two disability organisations about convivial encounters the people they supported experienced and staff practices that created these.

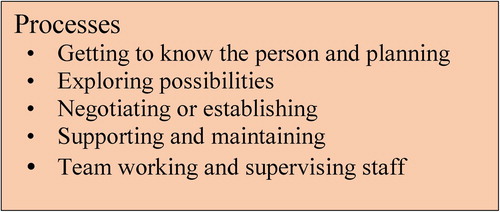

Results: Most commonly convivial encounters created involved repeated moments of shared activity through which people became known by name by others without disabilities. Eight approaches and five processes were used to create these opportunities for encounter.

Conclusions: The study provides a blueprint for scaling up or creating interventions to create opportunities for convivial encounters, and opens lines of enquiry about staff competences needed and parameters for costing this type of intervention.

Concepts of “encounter” and “conviviality,” are used by geographers to understand social dynamics and diversity of cities where most people are strangers rather than members of close-knit spatial communities (Fincher & Iveson, Citation2008). They also provide a new lens for understanding elements of the social inclusion of people with intellectual disabilities (Bigby & Wiesel, Citation2011; Bredewold et al., Citation2016; Simplican et al., Citation2015). Encounter was originally described by Goffman (Citation1961, p. 298) as effectively agreeing “to sustain for a time a single focus of cognitive and visual attention.” In an urban context encounters between strangers are potential catalysts for social inclusion, connecting people who are different and bringing them together briefly “over a project or matter of fleeting but common interest” and perhaps also enabling momentary shared identification (Fincher & Iveson, Citation2008, p. 70). When they are marked by friendliness and hospitality, Fincher and Iveson describe encounters as “moments of conviviality” or convivial encounters.

In the field of intellectual disability, exploration of encounter has disrupted the common binary of community presence (use of facilities or services available to everyone) and community participation (relationships between people with and without intellectual disabilities). Rather than creating a mid-point between these understandings of presence and participation, encounter research explores social interactions that occur in public or commercial spaces or that fall outside fully fledged relationships, shifting the focus from the normative to the diverse forms that community participation takes for people with intellectual disabilities (Bigby & Wiesel, Citation2019; Simplican et al., Citation2015). Studies show that people with intellectual disabilities experience convivial, exclusionary and non-encounters with people without disabilities (Wiesel et al., Citation2013). Scholars from sociology have begun to explore the meaning of non-encounters (Blonk, Citation2020) and from political science connections between encounter and freedom (Clifford-Simplican, Citation2020). This study is applied, focused on practice and strategies for creating and supporting opportunities for people with intellectual disabilities to experience convivial encounters.

Bigby and Wiesel (Citation2019) identified three types of convivial encounter involving people with intellectual disabilities; (1) momentary shared identification, moments of friendly interaction with strangers around a shared activity or identification. For example, interacting with other fans of a team at a football match; (2) moments of everyday recognition, fleeting friendly interaction with strangers without any form of shared identification, other than perhaps as a trader and customer, that acknowledge the right of a person to use the space. For example, expression of patience by another shopper while a person is supported to make a transaction, and, (3) repeat encounters and becoming known, regular and repeated momentary encounters involving shared identification or everyday recognition where people become known by name by others without a disability. A Dutch study observed the most common type of convivial encounters were moments of everyday recognition, which they described as “light moments of recognition” (Bredewold et al., Citation2016)

Disability researchers have explored the material base of convivial encounters that “cannot be coerced but can be encouraged by the right rules, the right props and the right places and spaces” (Peattie, Citation1998, p. 248). In terms of places and spaces, an Australian survey found convivial encounters were more likely in localities with lower social-economic profiles, higher social cohesion, and in regional towns or outer metropolitan suburbs (Wiesel & Bigby, Citation2014). Observations of people living in group homes, supported by staff to go out, found they were more likely to experience convivial encounters in places where activities were non-competitive, people had a common purpose and there were opportunities for verbal and non-verbal communication (Wiesel & Bigby, Citation2014, Citation2016). Two Dutch studies of projects, such as community gardens or urban farms, concluded that places with built-in social boundaries, shared purpose, clear roles and rules around participation and interaction, and ease of disengaging from social interaction were more conducive to encounters involving people with intellectual disabilities (Bredewold et al., Citation2016, Citation2019). In terms of props, dogs have been observed to facilitate convivial encounters in both Dutch and Australian studies (Bould et al., Citation2018; Bredewold et al., Citation2016).

Individual characteristics of people with and without intellectual disabilities have also been found to facilitate encounters. Younger people and those with relatives with intellectual disabilities were more likely to report having encounters (Wiesel & Bigby, Citation2016), while having a friendly disposition was a facilitating factors for people with intellectual disabilities having convivial encounters in community groups (Craig & Bigby, Citation2015).

Various studies suggest the significance of support worker practice in facilitating convivial encounters. An Australian study observed workers being alert to and supporting opportunities for encounter or gently managing moments of awkwardness or anxiety felt by either party (Bigby & Wiesel, Citation2015). The potential for support practices to obstruct or simply miss opportunities for encounter was also found in this study. Skills drawn from person-centred Active Support – a facilitative relationship to enable engagement in meaningful activities and social interactions, (Mansell & Beadle-Brown, Citation2012) – underpinned, though perhaps not consciously, practice of supporting these convivial encounters.

Encounter research has focussed on understanding places and spaces, props and support worker practices that maximise or take advantage of incidental opportunities for encounter in public or commercial places. However, there are strong similarities between the concept of convivial encounters and what Craig and Bigby (Citation2015) describe as “active participation” by people with intellectual disabilities in mainstream community groups or volunteering contexts, that is marked by shared activity and friendly interactions between them and people without disabilities. Studies identifying group features that facilitate active participation add to understanding about places and practices that facilitate convivial encounters. Facilitating group features include willingness of leaders and other members to support inclusion, acceptance of specialist advice or training about engaging a person with intellectual disability, presence of an integrating activity or common goal, and regularity of meeting (Craig & Bigby, Citation2015; Stancliffe et al., Citation2015). These two studies ran small demonstration programs (one of which was the Transition to Retirement program (TTR)) whereby researchers created individual opportunities for people with intellectual disabilities to participate in mainstream (non-segregated) groups or as volunteers. Researchers matched individuals with groups based on their interests, supported attendance and offered advice or training to other members about engaging with the individual with intellectual disability. These programs drew on support practices from co-worker training (Storey, Citation2003) and person-centred Active Support, indeed Stancliffe et al. (Citation2015, p. 704) used the term “active mentoring” to refer to the skills taught to community group members.

A scoping review of interventions to support community participation categorised the two programs (referred to above), as well as three others as being based on a conceptualisation of community participation as convivial encounter (Bigby et al., Citation2018). The review analysed the conceptual underpinnings of interventions, acknowledging that authors of papers categorised in this way had not directly used the term convivial encounters. Two other conceptualisations of community participation underpinning other different types of interventions were identified as relationships and as belonging. Interestingly, a subsequent study of an arts program for people with intellectual disabilities, which aimed to support community participation through increasing participants’ sense of belonging to the Arts community, was also found to lead to opportunities for convivial encounters between participants with shop keepers in the locality of the program (Anderson & Bigby, Citation2020). However. notably, the review found that only interventions based on convivial encounter included people with more severe intellectual disabilities. It also highlighted the limited evidence about the design or effectiveness of interventions to support community participation and the need for further research about these.

Aim

The aim of this paper is to explore how disability support organisations deliberately create opportunities for one type of community participation, convivial encounters, for people with intellectual disabilities. The research questions were (a) what types of convivial encounters did organisations create and (b) what approaches and processes did they use to create opportunities for convivial encounters.

Method

A case study design was used to enable an in-depth understanding of the social phenomenon, the creation of opportunities for people with intellectual disabilities to experience convivial encounters (Richards & Morse, Citation2012). Case studies utilise different types of data from multiple sources, to enable a richer picture to be developed than would occur by relying on any one single source (Yin, Citation2009). The data collected included perspectives from the people supported, staff at varying levels of seniority and written information in the form of annual reports, program and job descriptions and policies.

Data collection and participants

An industry reference group, comprising representatives from across the Australian disability sector, identified disability support organisations as offering “promising” interventions or programs of high quality that were similar to those categorised in the Bigby et al. (Citation2018) scoping review based on creating convivial encounters. The chief executive officers of two organisations in Victoria (Brookfield and Oakbank) were invited to participate, and information about the study was circulated by them to staff, participants and their families. The study was explained further by the researchers to those interested before they were invited to sign a consent form. A family member was involved in the consent process for participants who normally had this type of support for decision making. The study was approved by the University Human Ethics Committee. All names of participants and the organisations were changed to ensure anonymity.

Data about the interventions and perspectives of different stakeholders were gathered using semi-structured interviews and reviews of documents and reports. In Brookfield 11 staff were interviewed, including the CEO, managers, team leaders and front line support workers, and in Oakbank seven staff were interviewed across a similar span of positions. Consent for an interview and for staff to talk about the support provided to each individual was given on behalf of five people with intellectual disabilities supported by each organisation. Most of these participants required significant support with communication and participated in the interview with a support worker who knew them well. Interviews lasted between 45 and 90 minutes and were digitally recorded. They sought information about the offsite activities, social interactions and places the participants with intellectual disabilities were engaged in, the strategies staff used create and support these activities, and information about the way the organisation approached support. In addition, a family or staff member, who knew each participant with intellectual disabilities, well completed the short form of the Adaptive Behaviour Scale (SABS) Part 1 (Hatton et al., Citation2001) to provide an indication of their intellectual disability. The data were collected by the second author and a research assistant between February and October 2017 as the National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS) was being implemented in Victoria.

Analysis

All interviews were transcribed. A template approach to analysis was used to code the data both deductively and inductively (King, Citation2012). The initial template included codes for types of convivial encounters derived from Bigby and Wiesel (Citation2019), the activities around which and places they occurred. Further descriptive codes were added about strategies used by staff to create and support opportunities, skills and characteristics of staff, and the way organisations supported this. NVivo 10 software was used to manage and code the data initially. Through the analytical process constant comparisons were made between data from different sources within and across the programs (Charmaz, Citation2006). The analysis was completed by both authors who regularly discussed emerging codes. The full-scale score for Part 1 of the ABS was estimated from the SABS using the formula provided in Hatton et al. (Citation2001).

Findings

Organisations and participants

The ten participants with intellectual disabilities were aged between 19 and 48 years with a median of 32 years. Their adaptive behaviour scores ranged from 60 to 275 with a median of 195 with three scoring below 151, which is the cut-off often used to denote more severe intellectual disability (Mansell & Beadle-Brown, Citation2012). The organisations offered a range of day support and accommodation services. The day support offered was typical of diversified day centres in Australia, including centre- or hub-based skills classes, creative or leisure activities, supported employment and off-site support for community participation. Brookfield was located in a regional town, and Oakbank across several small towns on the outer urban fringes of Melbourne. The day support programs were similar, serving 97 and 98 participants, respectively, mainly on a 5 day a week basis between 9 am and 3 pm. In the fortnight, during which data were collected at Oakbank, the people supported spent approximately 63% of time off site, and at Brookfield approximately 66%. These off-site activities were the focus of the study.

Types of convivial encounters

The most common type of convivial encounter described by staff was the “repeat encounters and being known by name,” described by Bigby and Wiesel (Citation2019, p. 43). They involved an individual with intellectual disability having regular social interaction, around a shared activity or interest, with a person without a disability, who knew them by name. These convivial encounters occurred in very different types of places; commercial premises such as a café, public facilities such as swimming pools, institutions such schools, and public places such as streets. provides exemplar staff descriptions of convivial encounters, and illustrates the different contexts and activities around which they occurred. These included: participating in a water aerobics class, regular patronage of a café, volunteering in a school library, delivering biscuits to private homes, picking up jars from staff of a private business, and delivering meals on wheels to elderly people.

Table 1. Approaches to creating convivial encounters and examples of encounters and context in which they occurred.

Convivial encounters were generally brief, involving an exchange of greetings and small talk as an individual performed an activity such as making a delivery, ordering in a café, or paying the entry fee to a class. An individual might have a convivial encounter with several community members in the same place, such as Angela and Erica who, while they were chopping a fruit in a school, had interactions with multiple children who knew them by name. Some interactions were longer, when, for example the individual participated in activities in the same place for more than the fleeting time it might take to make a delivery. Convivial encounters were always between an individual and a community member, but there were instances where a small group of people with intellectual disabilities were present, as in the case of Angela and Erica at the school. The regular and repeated nature of these convivial encounters was tenuous, dependent on continuity of support from another person within a place, or from the organisation to enable getting to that place or in continuing to run a social enterprise.

There were fewer examples of the types of irregular convivial encounters described as “momentary shared identification” (Bigby & Wiesel, 2018, p. 4). Staff described creating opportunities for such encounters through staging events or classes aiming to bring together people with intellectual disabilities and members of the public, but did not give specific examples of the convivial encounters that occurred at these events. Joanne, a manager, said:

We run a series of workshops, through the social enterprise … We usually do have a mix - people from the community who actually pay to attend … Community members come in and have no idea it's specifically set up for the people we support. It runs beautifully. Everybody has a really good time.

Creating opportunities for convivial encounters – setting it up behind the scenes

Significant collective staff effort “behind the scenes” was involved in creating opportunities for convivial encounters. Joanne, describing a community member greeting an individual with intellectual disabilities said, “it looks like it's a happy accident but, really, you've put a lot in place to make sure that that works for that person, and that the outcome is really good.” John a team leader pointed out, that if staff were present when an encounter occurred, they were “in the background” making it happen rather than being the focus of attention. Talking about creating an opportunity for Dave, a person with intellectual disability, to hand out raffle tickets alongside a volunteer organiser at a community market, Lucy a support worker explained:

… he wouldn’t be getting our support as such but we can set it up … That might take three, four, five times [meeting the organisers or his family] … we are not standing by his side on a Sunday at the market doing it with him …

Processes for creating opportunities for convivial encounters

The five processes (see ) were evident in the work of staff and managers across both organisations and all approaches to creating opportunities for convivial encounters. Processes were iterative, rather than linear. For example, exploring possibilities was informed by and in turn influenced planning.

Getting to know the person and planning

Getting to know each individual well, and using this information to plan support for participation in activities with them was based on assumptions that knowing someone well was pivotal to providing support best suited to their needs. This was often a lengthy process involving multiple people; the individual, their family and other people in their lives either formally or informally. As senior manager Patrick suggested:

Our process is to begin by getting to know people and what their priorities and preferences and goals are … what really matters to each person and we don't think we can provide good support without knowing the individual.

… it's finding that very thing that someone will think they will like to do, or a skill that they can do, and breaking it right down to … You do enjoy doing this skill, so let's build something around that.

It's very, very personal, and it's flexible around that person. It needs to be what they need it to be, but then we need to develop the program around that … we work from the people that we support, out, not the other way around.

Planning also involved reviewing what was happening for an individual, and as support worker Linda said to the person she supported this meant seeing “how you’re enjoying things or whether you’d like to mix it up and do something different.” Each organisation had its own framework for planning and staff who led this process.

Exploring possibilities

All approaches involved exploring possibilities in “the community”. Staff used “community” generically to include the businesses, institutions, social or educational groups, government and non-government organisations, and members of the public in a locality. Exploration was an outward looking process, whereby staff searched for existing activities that the people they supported could join, or gaps that could be filled by creating new groups or enterprises. As one team leader said, “we look out before we look in. So we try to look at as many programs out in the community that we can access or we can participate in or that we can create” (Adrian). The volume of groups, public facilities and activities happening in the community surprised some staff, when they started exploring possibilities, as they had often only been aware of those associated with their own interests. Lucy, a support worker, said for example, “there’s a lot of programs out there – I would never have thought.”

Exploration was generally tied to a specific individual and informed by the planning process. It required creativity, and problem solving, thinking about what the person could do as well as what they couldn’t. As Anna, a manager said, talking about people with higher support needs who were coming to the program, “you’ve got to be creative and find something that’s very, very different … It’s looking at a niche that suits them. And like yes, that takes time.”

Exploratory processes could also be generic and speculative, laying the groundwork for future opportunities for as yet unidentified individuals. This took the form of raising awareness about the organisation in the community or building relationships to provide the foundation for future negotiation. For example, Anna talked about how she was cultivating a relationship with a small businessman with a future opportunity in mind:

… we will use him for work experience, and that’s why I keep the relationship going. … he also does deliveries, so we could put a person in a delivery truck with his other little guy that comes in here, who I’m also very friendly with. Because I want to be able to put a person in that delivery truck going around doing the deliveries, because then they’ll have access talking to other people in the community.

… connecting someone to a business or organisation that shares similar values, and that takes a bit of door knocking and research … when a new business may open I always pop in and introduce myself and so relationships are very important with businesses. [Heidi]

..each of the staff [are expected] to really dig into what they have in terms of their contacts and how they can use those to connect people that they support in a whole variety of things across a week. [John]

… it’s people you know, really, and that’s what happens in a small country town, like Jane working here. She ran the production company. Adrian knows so-and-so from footy club. That’s how it works. That’s how you get the connections out there. [Lucy]

Exploring possibilities was a continual process. As Adrian said about his team, “we never sit still. We’re always looking for more challenges in the community, whether it’s programs or taking on new challenges.”

Negotiating or establishing

Negotiating participation in activities followed from the identification of possibilities, individual planning and exploration. If possibilities could not be found among existing activities, then something new might be established around an individual, such as a new group, enterprises or community service. Inevitably, this also involved elements of negotiation. illustrates some new activities established.

Negotiating or setting up opportunities involved attention to details of when and where an activity would occur, what parts of it an individual would participate in, who would also be there and how the necessary support would be provided. Key components were breaking down activities sufficiently to enable an individual be engaged in specific parts and ensuring opportunities for regular contact with people without a disability. The length and frequency of engagement looked different for each individual but being passive and thus only present in a place was not seen as an option. As Sarah, a manager said:

It’s actually having a level of engagement in the way that you choose to engage in the community … that’s the key of participation. You can be in the community and still be isolated, but it’s how you feel connected to your community and how you are engaged.

… we have been up and we’ve spoken to one of the employees, probably the senior employee of the day, and we’ve done some work around her about how to instruct, that Maggie needs simple instructions, she needs regular check-ups, only one or two step instructions … and now the employee supervises her.

Negotiations also occurred around cessation of an activity for individual in a particular place if it was not working well for them. This might also involve keeping open that possibility which might suit someone else in the future.

One point of negotiation was often around perceptions of risk and a lack of confidence by community organisations in supporting an individual with intellectual disabilities, often based on assumptions that a support worker always needed to be present. As Adrian said:

Sometimes you’ve got to take a few risks … - there’s a couple [of opportunities] fallen over along the way. Where the community’s gone “no, no unless you’ve got a worker”. But we knew it could work … well that’s fine, we’ll keep the worker there but you know, you just try.

Establishing new groups, activities or enterprises meant, as Joanne said, building “from the ground up based on the skillset of the specific person we're looking at, and bringing community members in.” Examples were, establishing an art program at a community house, a cooking class in a residential aged care facility, a social enterprise growing, making and selling organic products. Similar to identifying existing opportunities, attention was given to breaking down activities or production processes to maximise opportunities for engagement suited to individual needs and preferences. Joanne highlighted this when she talked about the catalyst for a social enterprise making chocolate chip biscuits, “it was an idea that started around one lady's like for chopping chocolate - not just any chocolate - the round buddy. It was right down to the shape of the chocolate.” Staff illustrated the opportunities for engagement created by a social enterprise or a community service:

… that little shop that sells the jams. Brilliant! Then you say to people, we grow the produce, we bring it back in, we cook it in the kitchen with a qualified chef. We then sell it in the shop. It’s a whole production line. [Lucy]

Our drivers collect it, not our choppers. So, the guys that like driving, that like to say hello, that like to have a chat, that like to carry something - they do that. Again, it's a five or six stage process. It's not one person doing the whole thing. One person will collect it, they'll bring it to school - that's their job done. Then the other guys that like to chop will come in, chop it all up, deliver it. [Jim]

… you always have in your mind why you're doing it this way. It's really easy to put on a high tea and art show with no thought behind it, whereas there's a million reasons why it needs to be done this way.

… it’s very much a multifaceted reward … there's two things … One is the fact that it's social for the people we support with peers and then their interaction with the children at the school, and then also knowing that we're providing something healthy for those kids … it connects them, you know like we wouldn’t have fruit if wasn't for us.

so if you can fill a little gap, then that lifts the level of the people that we're supporting, quite high … We have a free delivery service with our biscuits, because we know that that person has just had a baby, she actually can't leave her house, she's not able to drive, so we will drop something off. Then we'll say, “Do you want your veggies dropped off?” The guys that we support then become a really important part of her life, for that reason, because that's so handy.

You have to sell enough product to make it sustainable for those that are working there. That always is your bottom line. It doesn't matter how creative, and great, and awesome it is, at the end of the day if we're not sustaining, it's not going to work.

Supporting and maintaining connections

Supporting repeated convivial encounters meant continuing direct support to the individual to get to a place or participate in the activity or to the natural supporters in the space where the activity was happening. A less direct form of support was regular checking in with natural supporters to provide advice or identify any emerging issues. For example, John described supporting as:

… it’s very, very gently and step by step, and people get the opportunity to say, “Hey, is there any issues?” … How is it working for you? Is there anything we need to change? How can we go about it? so it’s lots of behind the scenes work.

Support sometimes aimed to facilitate repeated convivial encounters becoming deeper social connections. For example, assisting an individual to initiate or reciprocate a friendly gesture by sending a birthday card or flowers. As a staff member explained she keeps looking:

for where that connection is going to be - and really keep on fostering it, and look very carefully at what the people we support can give back to that friendship … initially, a friendship is very much one-way. You need to figure out what it is that the other person in the friendship needs, that you can support that person to either give, provide, or be a part of.

We link people back. The people that are involved in the project and the people that have come to volunteer on that day have formed a really good relationship now, whether we are there or not. Therefore, we involve those same people on our next project.

Team working and supervising staff

Teamwork was perceived as integral to successfully creating and sustaining opportunities for convivial encounters, as were staff attributes of valuing human rights, flexibility, initiative, and community connections. This work was seen as harder, requiring more judgement and creatively than normally expected of support workers, if compared to what was taught in certificate 3 or 4 courses. Many of the processes described required staff to work “in the community” away from co-workers, interacting with members of the public, natural supporters and individuals whom they supported. The situations they found themselves in were often unpredictable and had few parameters, other than the overriding purpose of the program. This meant staff had to take the initiative or make judgements and problem-solve on their own. As a team leader said:

It is allowing people to have the freedom, they don’t actually need to check in. I want people to feel empowered to look at what is out there and how that works for someone that they support. [John]

While managers recognised the importance of values, skills and knowledge, they prioritised values when recruiting staff. There was a strong view that staff could be trained in skills and provided with knowledge, but these were insufficient without the right values and these could not be taught. Patrick asserted that his organisation, first and foremost required staff to value “human rights, treating people with respect, treating people with dignity” and if this were the case then, “other things fly from that.” If skills were taken into account in recruitment, these were likely to be technical or creative, such as IT or art, and the ability to teach or share these rather than those related to disability support. Given the breath of potential activities that the people supported might be interested in or want to explore, managers aimed to build a team with diverse rather than similar skills, as Anna said:

Our staff don’t mix a lot socially because they all have different interests … when we recruit we might say we’re missing something in music or we’re missing whatever, and we try to recruit to fill that gap. But also when we recruit … we generally recruit people who have played team sports.

… you work in a team but you work in isolation … we’ve got 25 in our team - there could be five that don’t see each other than at the team meeting on … it’s that cohesion that everyone really knows everyone’s role, so if they had to step up they could fill in. [Anna]

Discussion

These findings demonstrate the potential for people with mild and more severe intellectual disabilities to experience one type of community participation; repeated convivial encounters around shared activity or identification through which they become recognised and known by name by others without disabilities. They illustrate the breadth of activities around which encounters occur and well as places they take place. The findings contrast with those of previous studies that highlight the predominance of fleeting more momentary and anonymous encounters (Bigby & Wiesel, Citation2015; Bredewold et al., Citation2016). This is likely due to the focus of these studies on incidental opportunities for encounter rather than more deliberate creation of them.

The findings delineate eight approaches (see ) and five processes (getting to know the person and planning; exploring possibilities; negotiating or establishing; supporting and maintaining; and, team working and supervising staff) used to create opportunities for convivial encounter. Much of this work is invisible and happens “behind the scenes” and thus runs the danger of not being acknowledged in funding regimes or by disability support organisations. Making it explicit contributes to the evidence base about the design of programs to support community participation, and helps to inform funders about necessary processes to fund, employers about the types of skills necessary for this type of work and importantly planners, people with intellectual disabilities and their families about what to look for services offering this type of support.

In some respects the processes identified in this study were similar to those of the demonstration of TTR program, which focussed on a specific group i.e., older people and used only one approach to creating opportunities for encounter i.e., identification of existing groups (Bigby et al., Citation2014). Designed for older workers transitioning from sheltered employment, the first TTR stage was “promoting retirement” to people and their families. The second, “laying the groundwork,” by building trust and knowledge about the project in a locality was similar to building relationships and raising the profile of organisations that were part of “exploring possibilities” in the current study. The third TTR stage, “constructing the reality” tailored support to each participant, and involved; person-centred planning, locating suitable a group, mapping new routines, recruiting and training members of the group as mentors, and monitoring and providing ongoing support when necessary to the individual, group members or others involved in the person’s life. These TTR third stage tasks were similar to some of those in the current study, although rather narrower and more specific to the “active mentoring” type of support offered to natural supporters in groups. Overall, the current study described processes for creating opportunities for convivial encounters at a more conceptual level and in greater depth than previous studies. This should assist in translation and informing design of interventions to create opportunities for convivial encounters for people of different age groups or with more severe as well as mild intellectual disabilities.

By detailing five processes this study has added knowledge about the creativity and skills required for the work of creating opportunities for encounters. As is often the case in other types of disability work, personal attributes of staff, such as human rights values were emphasised by employing organisations over skills which were perceived as easily taught. It is, however, important to articulate the skills to be taught in order to develop training. These findings provide insights into the different but complementary skills needed; micro-skills for direct support of individuals with intellectual disabilities “in the moment” (primarily person-centred Active Support); meso-level skills for identifying, understanding and negotiating with organisations, groups and communities (community development skills); and, skills for supporting decision making and working with individuals and their families around planning (most commonly seen as social work or casework and supported decision-making skills). Collectively, the data from this and the other studies about creating or supporting convivial encounters or active participation in community groups (Bigby & Wiesel, Citation2019; Bredewold et al., Citation2016, Citation2019; Craig & Bigby, Citation2015; Stancliffe et al., Citation2015; Wilson et al., Citation2015) provide the foundation for developing a set of staff competences and associated training for this type of work.

The nature of the processes necessary to create opportunities for convivial encounters suggests they may be best delivered by a team with diverse skills. Few individuals are likely to have the mix of micro, meso and case work skills necessary for this type of work. Having a team brings together staff with different skills, as well as ensuring the collaboration and supervision needed. The staff time dedicated to each individual needs to be flexible as it varies over time and with each process, and some tasks, such building relationships and reputation or initiating social enterprises are not necessarily specific to any one individual. These factors suggest creating opportunities for convivial encounters is better suited to delivery by organisations able to provide individualised support concurrently to a number of people, thus spreading the costs and benefits of less individualised tasks and more collective work across several people. In other words, a sole worker, particularly one only experienced in direct support work, is likely to find it difficult to deliver this type of intervention.

Staff referred to various unpaid activities in which individuals participated as work or work experience, or volunteer work. For example, one individual was supported to “work” for two hours a week in the office of an accountant, and several people delivered papers as part of a contract held by the organisation with a distribution company, yet were unpaid. This raises issues about the need for organisations and funding streams to more clearly distinguish between the primary purpose of support to ensure people with intellectual disabilities are not inadvertently exploited or subject to mixed messages that muddle community participation with paid employment.

Limitations and future research

This study was conducted in Australia on the cusp of the transition from block funding for disability support programs to individualised funding as part of the NDIS. Having identified the processes and skills required to create opportunities for convivial encounters an important next step is to analyse individualised costs in the context of the new NDIS funding regime. These findings help in thinking about parameters of cost by showing not only necessary processes but also the potential variable intensity of effort and thus costs over a period of time as support progresses through different processes, or the intensity of direct in the moment support changes, or an existing opportunity stalls and a new one needs to be created. The findings also demonstrate the high proportion of “behind the scenes” work that does not meet the standard criteria of face-to-face direct support, organisational or staff overheads. They suggest that individual costing or funding for the type of invention delivered by the organisations in this study should be averaged and allocated over a period of 12 months or more, rather than tied to hours of weekly direct face-to-face support.

The organisations in this study were located in outer urban localities and a regional town and its outlying districts, similar to those which earlier research suggests are conducive to convivial encounters (Wiesel & Bigby, Citation2014). However, it will be important for future research to explore the potential of inner urban locales as places for creating opportunities for convivial encounters. They are likely to offer a similar wide array of diverse groups, organisations and commercial businesses but dispersed over a wider geographic area.

Many people with intellectual disabilities, particularly those more severe impairments, will always need support to reach the places or participate in the activities around which convivial encounters occur. This study makes explicit the collaboration between disability organisations and other groups, organisations and members of the public that facilitate such opportunities. Some community members have had little exposure to people with intellectual disabilities and feel ill prepared to interact (Bigby & Wiesel, 2018). A by-product of the work of disability organisations associated with creating opportunities for encounter was increasing the visibility of people with intellectual disabilities and helping to educate members of the public to be comfortable and confident in interactions albeit usually focussed on particular individuals. These are important stand-alone tasks that could be taken on more comprehensively by local authorities through training for the community groups or leisure centres they fund and encouraging them to be inclusive. An initial strategy might be an audit of groups and facilities in each local authority to establish how many include people with intellectual disabilities or whether staff are confident in being inclusive. This broader community development work can be funded by the ILC program of the NDIS. It will pave the way for the more individualised work of disability support organisations, and also help to ensure places and spaces are more conducive to convivial encounters for the wider community of people with disabilities.

Conclusions

This study had added to knowledge about the material base for convivial encounters, by exploring how two organisations created opportunities for repeated encounters for people with more severe and milder intellectual disabilities. Using the nomenclature of convivial encounter, as a form of community participation, adds to the lexicon describing support options and helps to avoid the often ill-defined or vague intentions of disability day support programs of the past. In the context of individualised funding greater clarity about available options assists people with intellectual disabilities to exercise choice about their preferred form of participation and helps to make organisations more accountable for what they deliver. This study opens up further lines of enquiry about the staff competences and training needed for inventions aiming to create and sustain convivial encounters, and provides the parameters for modelling costs and a blueprint for scaling up or creating new interventions of this type.

Acknowledgements

An early version of this paper was presented at the 2018 IASSID Europe Congress in Athens as part of a symposium on convivial encounters. National Disability Services (NDS) was the industry partner and coordinated the Industry Advisory Group.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Anderson, S., & Bigby, C. (2020). Community participation as identity and belonging. A case study of arts project Australia. Research and Practice in Intellectual and Developmental Disability, https://doi.org/10.1080/23297018.2020.1753231

- Bigby, C., Anderson, S., & Cameron, N. (2018). Identifying conceptualizations and theories of change embedded in interventions to facilitate community participation for people with intellectual disability: A scoping review. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 31, 165–180. https://doi.org/10.1111/jar.12390

- Bigby, C., & Wiesel, I. (2011). Encounter as a dimension of social inclusion for people with intellectual disability: Beyond and between community presence and participation. Journal of Intellectual and Developmental Disability, 36, 263–267. https://doi.org/10.3109/13668250.2011.619166

- Bigby, C., & Wiesel, I. (2015). Mediating community participation: Practice of support workers in initiating, facilitating or disrupting encounters between people with and without intellectual disability. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 28, 307–318. https://doi.org/10.1111/jar.12140

- Bigby, C., & Wiesel, I. (2019). Using the concept of encounter to further the social inclusion of people with intellectual disabilities: What has been learned? Research and Practice in Intellectual and Developmental Disability, 6, 39–51. https://doi.org/10.1080/23297018.2018.1528174

- Bigby, C., Wilson, N., Stancliffe, R., Balandin, S., Craig, D., & Gambin, N. (2014). An effective program design to support older workers with intellectual disability participate individually in community groups. Journal of Policy and Practice in Intellectual Disability, 11, 117–127. https://doi.org/10.1111/jppi.12080

- Blonk, L. (in press). Micro-recognition, invisibility and hesitation. Theorising the non-encounter in the social inclusion of people with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Journal of Intellectual and Developmental Disability, [in forthcoming special issue on Enconter].

- Bould, E., Bigby, C., Bennett, P. C., & Howell, T. J. (2018). ‘More people talk to you when you have a dog’– dogs as catalysts for social inclusion of people with intellectual disabilities. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 62, 833–841. https://doi.org/10.1111/jir.12538

- Bredewold, F., Haarsma, A., Tonkens, E., & Jager, M. (2019). Convivial encounters: Conditions for the urban social inclusion of people with intellectual and psychiatric disabilities. Urban Studies, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098019869838

- Bredewold, F., Tonkens, E., & Trappenburg, M. (2016). Urban encounters limited: The importance of built-in boundaries in contacts between people with intellectual or psychiatric disabilities and their neighbours. Urban Studies, 53(16), 3371–3387. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098015616895

- Charmaz, K. (2006). Constructing grounded theory: A practical guide through qualitative analysis. Sage.

- Clifford-Simplican, S. (in press). Freedom and intellectual disability: New ways forward for the concept of encounter. Journal of Intellectual and Developmental Disability [Special Issue on Encounter].

- Craig, D., & Bigby, C. (2015). “She’s been involved in everything as far as I can see”: supporting the active participation of people with intellectual disabilities in community groups. Journal of Intellectual and Developmental Disability, 40, 12–25. https://doi.org/10.3109/13668250.2014.977235

- Fincher, R., & Iveson, K. (2008). Planning and diversity in the city: Redistribution, recognition and encounter. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Goffman, E. (1961). Encounters: Two studies in the sociology of interaction. Penguin University Books.

- Hatton, C., Emerson, E., Robertson, J., Gregory, N., Kessissoglou, S., Perry, J., Felce, D., Lowe, K., Walsh, P. N., Linehan, C., & Hillery, J. (2001). The adaptive behavior scale-residential and community (part I): Towards the development of a short form. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 22, 273–288. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0891-4222(01)00072-5

- King, N. (2012). Doing template analysis. In G. Symon & C. Cassell (Eds.), Qualitative Organizational research (pp. 118–134). Sage.

- Mansell, J., & Beadle-Brown, J. (2012). Active support: Enabling and empowering people with intellectual disabilities. Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

- Peattie, L. (1998). Convivial cities. In M. Douglass & J. Friedmann (Eds.), Cities for citizens: Planning and the rise of civil society in a global age (pp. 247–253). Wiley.

- Richards, L., & Morse, J. M. (2012). Readme first for a user's guide to qualitative methods. Sage.

- Simplican, S. C., Leader, G., Kosciulek, J., & Leahy, M. (2015). Defining social inclusion of people with intellectual and developmental disabilities: An ecological model of social networks and community participation. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 38, 18–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2014.10.008

- Stancliffe, R. J., Bigby, C., Balandin, S., Wilson, N. J., & Craig, D. (2015). Transition to retirement and participation in mainstream community groups using active mentoring: A feasibility and outcomes evaluation with a matched comparison group. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 59, 703–718. https://doi.org/10.1111/jir.12174

- Storey, K. (2003). A review of research on natural support interventions in the workplace for people with disabilities. International Journal of Rehabilitation Research, 26, 79–84. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004356-200306000-00001

- Wiesel, I., & Bigby, C. (2014). Being recognised and becoming known: Encounters between people with and without intellectual disability in the public realm. Environment and Planning A, 46, 1754–1769. https://doi.org/10.1068/a46251

- Wiesel, I., & Bigby, C. (2016). Mainstream, inclusionary and convivial places: Locating encounter between people with and without intellectual disability. Geographic Review, 106, 201–214. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1931-0846.2015.12153.x

- Wiesel, I., Bigby, C., & Carling-Jenkins, R. (2013). ‘Do you think I’m stupid?’: Urban encounters between people with and without intellectual disability. Urban Studies, 50, 2391–2406. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098012474521

- Wilson, N. J., Stancliffe, R. J., Gambin, N., Craig, D., Bigby, C., & Balandin, S. (2015). A case study about the supported participation of older men with lifelong disability at Australian community-based Men's Sheds. Journal of Intellectual and Developmental Disability, 40, 330–341. https://doi.org/10.3109/13668250.2015.1051522

- Yin, R. K. (2009). Case study research: Design and methods (4th ed.). Sage.