ABSTRACT

Background:

The transition from school to adult life is challenging for young people with intellectual disability. The study aimed to explore how young people with intellectual disability themselves experience the transition from school to adult life.

Methods:

A co-designed, qualitative study. Thematic data analysis of qualitative survey responses, semi-structured interviews, and focus groups with 27 young people with intellectual disability in three Australian states.

Results:

Participants found transition planning at school inconsistent or lacking and felt excluded from decision-making about their lives. Accessing meaningful services, training, and employment beyond volunteering was challenging and enduring, leaving participants in perpetual state of transition, feeling lost, and missing out of post-school adult milestones.

Conclusions:

Policy, system, and service gaps must be addressed with a nationally consistent and accountable approach that truly supports choice and control for young people with intellectual disability in transitioning from school into meaningful adult lives.

Transitioning from school to post-school activities is well known to be challenging for young people as they seek to develop their own identity and opportunities for meaningful roles and occupations. For young people with intellectual disability, poor support with transition planning and navigating complicated policies and services, compound the challenges of post-school transition (Dyke et al., Citation2013; K.-R. Foley et al., Citation2013; Hudson, Citation2003; Redgrove et al., Citation2016). Young people with intellectual disability may struggle with negotiating the transition from a structured and supported school environment to contexts characterised by “wide variation in adoption of adult roles related to employment, independent living, friendships, and day activities” (Dyke et al., Citation2013). For many, the transition includes reduced participation in employment and tertiary education, isolation, and mental health difficulties (Ashburner et al., Citation2018). Thus, transition experiences of many young people with intellectual disability may be markedly different to their peers without disability (Young-Southward et al., Citation2017). So too are their post-school outcomes across all life domains (Mazzotti et al., Citation2021).

In defining transition, Smith and Dowse (Smith & Dowse, Citation2019, p. 1327) observe that transition from school to adulthood is often conceptualised as a series of “achievable and natural steps,” illustrating the idea of “normative” transition markers. This definition is problematic, creating expectations of a linear pathway of progression and placing responsibility on the young person (and their families) to “achieve” (Redgrove et al., Citation2016). Secondly, it reinforces the idea that transition occurs outside a socio-cultural context. Context is critical to understanding the experiences of young people with intellectual disability, especially as it relates to the burden of stigma and low expectations – from self, family, teachers, service providers, and employers (Meltzer et al., Citation2020). In this article, we define transition as the process of planning and preparing to leave school, including supports and opportunities to achieve meaningful goals and activities after school, such as further study, voluntary and paid work, as well as relationships, and leisure activities.

Transition policies

In Australia, there is a general acknowledgement in the National School Reform Agreement (Council of Australian Governments, Citation2018) that planning for transition out of school is imperative for all young people, so they “gain the skills they need to transition to further study and/or work and life success” (p. 7). Individual states have policies and best-practice frameworks for the general school population (e.g., NSW Government, Citation2016) and also provide guidelines on how to support students with disability to leave school. Shared characteristics between these guidelines are that planning should begin early, be person-centred, and ensure collaboration between the family, school, and services (e.g., NSW Government, Citation2019; Queensland Government, Citation2021). Suggested post-school options include pathways to employment, education or training, voluntary work, and community participation. However, previous studies have established links between poor post-school outcomes and ineffective collaboration between school systems, adult disability services and the paid and unpaid workforce (Meadows et al., Citation2014). People with intellectual disability continue to have low rates of employment and many are underemployed (Zhou et al., Citation2019). In 2020, the ABS reported only 32% of people with intellectual disability were employed, compared with 83% of people without disability (Australian Bureau of Statistics, Citation2020). Further, only 6.9% of people with intellectual disability receive specialist services designed for open employment, of which only 50% actually obtain open employment (Meltzer et al., Citation2020).

Transition planning

An emerging body of evidence focused on transition experiences of young people with intellectual disability demonstrates that post-school outcomes improve when transition planning starts early (see e.g., Foley et al., Citation2012), is coordinated, and brings together all the key stakeholders: students, families, educators, community members, and service organisations, see for example “Taxonomy for Transition Planning” by Kohler et al. (Citation2016). In Australia, however, it seems that transition planning for many young people with intellectual disability occurs in their final year of school and can be narrowly focused, frequently targeting only the transition into adult disability support services, with limited consideration of broader individual needs and goals of the person (Leonard et al., Citation2016; Redgrove et al., Citation2016). In recent years the roll out of the National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS) (Australian Parliament, Citation2017), a market-based system, may have brought about change in transition experiences with its focus on individualised funding. It is intended to enable individual “choice and control” and access to school leaver support as part of transition planning from Year 10, but only recently include a focused “Participant employment Strategy” and action plan (National Disability Insurance Agency, Citation2022a).

Research on transition experiences

In the past 10 years, there has been an increase in qualitative studies hearing directly from young people about their transition experiences. Few studies have been co-designed, several have included young people’s voices on transition (e.g., Bennett et al., Citation2017; Garolera et al., Citation2021; Hughes et al., Citation2018; Lawson & Parker, Citation2020; Pearson et al., Citation2021), while others have placed more reliance on parents or professionals (Gauthier-Boudreault et al., Citation2017; Jacobs et al., Citation2018; Young-Southward et al., Citation2017). Hearing young people’s own voices is imperative to understand their experiences of transition. Voices of parents and professionals will likely include different experiences and priorities for young people transitioning to adulthood.

This article is drawn from a larger mixed methods study that aimed to explore how young people with intellectual disability experience the transition from school to adult life by including young people, their parents, educators, and disability service providers as participants. In this manuscript we present findings from the qualitative data on the experiences reported by young people who had left school. We include their experiences while at school, preparing to leave high school, and after leaving school, engaging with disability services, and participating in education, training, and employment. The perspectives of other participants are reported in separate, forthcoming manuscripts. In the discussion section, we consider the young people’s experiences in the context of significant changes in disability funding and consumer services with the introduction of the NDIS, and whether these differ from those reported in previous qualitative research.

Method

Study design

This qualitative study was part of a larger mixed methods project co-designed by academic researchers and an advisory group of young people with intellectual disability. Study participants contributed their views and experiences using online or paper surveys, or by participating in semi-structured individual interviews, and/or focus groups.

Advisory group

A Sydney based youth advisory group of five young people with intellectual disability (aged 18–25) provided guidance with the study design. The researchers pitched the multi-stage, mixed methods study to the group members, who agreed that the study focus was important. They gave examples of issues that had challenged and helped them when leaving school and in seeking meaningful post-school activities. They reviewed and refined some of the draft questions and provided suggestions on additional topics to be included. They also provided input on interview style and survey format. Due to delays in completing the study, advisory group members were not available to provide guidance with the findings.

Participants and recruitment

Our recruitment of young people with intellectual disability aged 18–25 years who had left school was purposive and inclusive. Our final sample included a few older participants as it soon became apparent that the “transition” period for young people with intellectual disability often continues into their third decade as also identified by Hudson (Citation2003). Recruitment strategies including social media campaigns, contacting disability organisations, and local Primary Health Networks. We also presented the project at disability conferences and operated stalls at disability expositions (Expos) in the cities of Sydney, Brisbane, and Melbourne, providing information and opportunities to participate.

Accessible participant information was developed for survey, interviews, and focus groups. Before survey questions were shown, consent was taken to be implied by participants completing and submitting the form online. For interviews and focus groups, we obtained informed and supported consent from young people, and from parents or carers if the young person was unable to consent. Before beginning interviews, we established rapport with participants, told them about ourselves and this research. We carefully explained the details of the study information to participants and discussed the meaning of research and consent along with their right to decline questions or withdraw from the study at any time. All interview and focus group participants received a $50 gift card in appreciation of their time.

Data collection instruments

Qualitative survey and interview questions were developed with the Advisory Group, from relevant literature, and key points from Australian transition policies and guidelines, to understand young people’s experiences of transition planning, leaving school, and starting post-school activities (see ). The online survey housed on Qualtrics software (Qualtrics, Provo, UT) included demographic questions, fixed answer questions, and similar qualitative questions as those used in interviews and focus groups including experiences of transition planning and supports, and opportunities after school. Only qualitative question responses are reported here. Only young people over 18 years of age who had left school were included. A screening question led respondents who answered that they had not yet left school to the end of the survey.

Table 1. Interview and focus group questions.

Data collection

The dataset was collected through six individual interviews, and two focus groups. Also included are responses from eight survey participants who had provided free text answers. Four young people were interviewed individually, two at the disability Expos in Brisbane (LM, GD), and Melbourne (LM, JM), and two by videoconference (GD). Following one focus group, two participants opted to also partake in individual interviews (NS). On average interviews lasted 30–45 min. Parents were present with some participants, at their request, and provided clarification as needed. The two focus groups took place on two different service provider premises in Sydney with ten and five participants respectively. Each focus group lasted 1.5–2 h. Two researchers attended each focus group (LM, NS), one to facilitate discussion, and one to observe, take notes, and to make sure all participants were included. Support workers were present and assisted with clarification, and sometimes reminded participants of experiences that could be relevant for the study. Interviews and focus groups were digitally recorded with participant permission, and professionally transcribed verbatim.

Analysis

Interview and focus group data, along with anonymous text responses included in the survey, were analysed using NVIVO QSR International Pty Ltd software (2020) NVivo. Reflexive thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, Citation2019, Citation2021) was used to systematically identify and organise patterns of meaning embedded within the qualitative data. The analytical process commenced with critical reading of transcripts to become familiar with the data. To maintain the perspectives of young people each transcript generated from each interview was first coded inductively. These codes were refined through discussion between team members. Once no new codes were identified, the researchers categorised data holding conceptual similarity under broader codes responding to research aims. Through discussions the team agreed on common codes across transcripts that best encapsulated the experiences of transition, and with further analysis led to generation of initial themes and sub-themes. A thematic map was constructed to provide a visual summary of prospective themes and their relationships (Braun & Clarke, Citation2021). The initial themes were reviewed in relation to the full dataset, the research question, and broader objectives, and then developed based on this review. Finally, themes were revised and defined to bring together the story being communicated by the data in relation to the research question in a final written interpretation (Braun & Clarke, Citation2019). No statistical analysis was completed on survey data due to a limited sample size.

Trustworthiness

Field notes during data collection in multiple organisations, and reiterative reading and coding of transcripts supported analysis. To enhance trustworthiness, a reflective journal that documented the research process, as well as the reflections and insights of the researcher was maintained to encourage reflection in the analysis process and provide transparency (Braun & Clarke, Citation2021). The research team engaged in peer debriefing through regular team meetings, and collaborative coding was conducted to ensure a systematic and thorough interpretation of findings and thus enhance credibility.

The study had approval from Western Sydney University Research Ethics Committee (approval number H12807).

Results

The findings presented here are drawn from the responses of 27 young people including 15 female and 12 male participants aged 19–33 years. illustrates the characteristics and demographics we were able to collect from all participants. All identified as having intellectual disability described as mild or moderate. Most participants were from NSW, which is reflective of the location of the researchers during the Covid-19 pandemic and the travel restrictions imposed between Australian states during 2020–2021. Twenty participants lived with their parents, two lived with extended family, two lived in group homes, two on their own with support, while one reported having no stable accommodation. Most participants described having received support at school. Their experiences varied between receiving support within a mainstream class from a teaching assistant and/or task adjustments with some or all subjects. Others were placed in a smaller “special” class settings with fewer students and more teaching assistance, and an adjusted curriculum, sometimes referred to as “Life-skills.” Commonly participants had experiences with being in both “mainstream” and “special” classes, especially in high school. After leaving school, the majority (17) of young people were in disability services; eight were engaged in a combination of studying, working and/or volunteering; one young person said “she was doing nothing,”, and one did not disclose.

Table 2. Characteristics of young people who participated in the study.

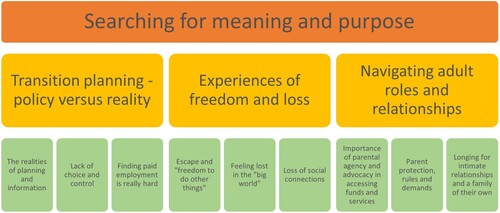

Themes – searching for meaning and purpose

The analysis of the rich data produced with the young participants in this study generated an overarching theme, and three key themes with three sub-themes as illustrated in . The overarching theme “searching for meaning and purpose” was a sentiment expressed by most participants about their lives, but especially by those who had left school several years ago. There was a sense that most participants had not reached a purposeful destination but were caught in a perpetual state of transition with a disability service or moving between services. Few felt that they were receiving the right support to help them achieve major goals or outcomes of importance to them. The key themes and sub-themes developed from the data are presented below with selected extracts from interviews to highlight the experiences young people shared with us.

Theme 1 – transition planning – policy versus reality

The realities of planning and information

The experiences of transition planning before leaving school varied significantly between participants with inconsistencies in both processes and timing, and in terms of the opportunities and support they received. Few had experienced choice, autonomy, or control in planning post-school goals and services. Provision of information and support linked to the young person’s goals was often lacking.

Many times, young people reflected on their experiences, both positive and negative, being linked to the skills and approach of a particular individual staff member, rather than a consistent offering based on best practice and systemic procedures. For example, one young person reflected that her maths teacher “was amazing … she just – she knows how to speak to people who were different” and that she had spoken to her about “what I might do after school.”

Yes. It’s – I can't remember. It's something – like, even, like, the principal, like, I was, like, very close and everything and, um, they asked what I wanted to do, I honestly don’t know, whatever comes up I guess … I wanted to be a hairdresser or a masseuse; maybe something around there, yeah. (Amelia)

No, because during high school they kept telling me that I'd be no good at anything else. So that’s the way my mind kind of worked at the time, and now. I'm like, no, I want to do more. (Kirsty)

We had a careers advisor which – which helped us to find out what we want to do … well, basically … the careers advisor said, “I give up on you bunch; I’m out of here" … So in Year 11/Year 12 the career advisor was basically just, off they went. (Paul)

Lack of choice and control

As well as not being afforded advice and forward planning, some of the young people gave examples of times where choices were made for them at school based on assumptions about what they wanted to do in the future. Paul stated that having teachers assuming his preferences was just plain wrong, and their assumptions were incorrect anyway:

… because there was this one time where the head teacher of the mainstream … , got there and said, “Okay, I'll choose your elective for what you want to do in Year 11,” and I was like, excusez-moi, that's not even – that's not even correctomondo, thank you very much. (Paul)

For Paul, the override by school staff of his autonomy would lead to conflicts when he asserted his right to choose for himself:

… you know, that's why I ended up actually having the argument with the head, um, with the head teacher of the thing and it ended up being really quite unpleasant, um, you know, because I realised that something was not right, but no one was giving me any heads up or anything. (Paul)

Young people also reflected on the limited choice of services in their area, or the fact that the available services did not offer programs that suited their interests and priorities, as explained by Amelia:

it’s been really tricky and hard … in fact … because last year I was like – we went around, um, all different types, um, like, companies and it was, like, really hard to find which one, um, um, I'm interested in, like [names of three different service organisations] and everything … (Amelia)

Finding paid employment is really hard

For several participants, life goals often remained undefined and/or unfulfilled after leaving school. Most of our participants talked about how they wanted to find a job – a paid job, to enable independence. Some of them had been engaged with disability services for more than eight years, completed one or more courses at TAFEFootnote1 (Tecnical and Further Education), gained some work experience and contributed as volunteers, but very few had opportunities for employment, let alone ongoing paid employment. The only two participants who had ongoing paid jobs, were both working with family members or in their family’s business. While several participants in one focus group (James, Susan, David, Shyla, and Paul) were completing TAFE courses online, facilitated by their current service provider, they explained that they had spent years hoping to gain job training and meaningful employment through employment agencies. Some were yet to work out what options they had, and commonly felt that they had little support from post-school services to refine and achieve their goals.

Several of these young people had switched between service providers in the hope of finding support or programs toward employment and training, but promised services were often not delivered. According to Paul, even with several completed TAFE courses, the experience of looking for a job was frustrating and like waiting to win the lottery: “So you're just waiting here for that lottery ticket to draw your name out.” Paul eloquently described his experience with an employment service that he felt did little to support his search for employment:

So they're basically, you know, um, not very well, um, structured. All they were doing with me was saying, “What do you want to do? What do you want to do?” instead of going, okay, let's go through the process of, you know, getting you a job, getting you rent, getting you out there for work experience and that … they were a total nightmare. (Paul)

Despite engaging with service agencies and organisations that were supposed to assist with job training and employment, individual participants reached out to the researchers on several occasions during interviews and focus groups with questions on how to get a job and asked the team for help in finding jobs. For example, Jack said:

Um, so in a job, right, can you teach me how to get a real job? Because I wonder if anyone can help me get a job … I trust my mum, but I’m mainly trusting myself or someone else I know. It’s really hard. (Jack)

Because I feel that, sometimes, um, you know, want to – that I want to do some more in life than just, be a disability person. And I want to be … I want to be out there. Know what I mean? (Hayden)

Theme 2 – experiences of freedom and loss

Escape and “freedom to do other things”

We asked the participants about the best and the hardest thing they experienced when leaving school. Several participants had found school life challenging both academically and socially, and for some there was a strong sense of freedom and relief from leaving school. The best parts about leaving school focused on “having the freedom to do other things” (Elena) and getting away from a restrictive environment where they were told what to do by “annoying teachers” (Olivia). Olivia also enjoyed that there was “no more homework,” while Sarah expressed a much stronger sense of relief in leaving school “getting away from a toxic environment that stifles any creativity or individuality.” Shyla was relieved to “leave the negativity behind … because I didn't like talking to people there because I was pretty shy, and I still am now.”

Feeling lost in the “big world”

There were many challenges connected with leaving school and young people expressed as a sense of feeling a bit lost or as Jack put it, feeling “scared and nervous” in a new world. Sofia said that while she enjoyed not having the pressures she had felt at school in terms of “presenting a certain way,” since leaving school she had struggled with isolation and “not knowing how to function without a schedule.” Mia stated that she found “most things” hard after school, while several other participants expressed a sense of loss of the structure and support system that school had provided in their lives. Mia found life hard with “no routine,” and Elena stated that “finding her way in the big world” had been difficult, a sentiment that was shared by other participants. Some said that they were sad to be “saying goodbye to a few of the teachers” (Olivia) who had really helped them, and now missed the structured programs where they had friends, felt supported and/or had experienced success. Noah said, “I miss not having dance and drama classes anymore,” and Hayden explained how important performing arts was for him and that the hardest thing was to leave the hip hop ensemble he had been part of for three years:

… leaving the group three terms in, you know, and not being there for the final, you know, term four the … you know, for the group, just – it was really difficult for me and – and I – I cried most of the time, like, and I just couldn't think about, like, the hip hop ensemble without getting sad and freaked out … (Hayden)

Loss of social connections

Leaving school had for many of the participants meant the painful loss of friendships. For Sofia the “isolation” after leaving school had been hard, and others talked about feeling sad about leaving their friends, and how they were missing these friends in their everyday lives.

Actually, um, you know, like, um, like, when I left school, I left a good mate of mine … Um, he and I used to hang out together all the time. Um, ah, he and I were in the same class together when I was in Year 12 surprisingly, um, and leaving him was a bit tough as well so, yeah. (Hayden)

Um, but also it was – it was hard to fit in at school, to be perfectly honest, and – and when it came to, like, graduating school I – I kind of felt on the outs because – because – because I didn’t really get to hang out with other people much because they were graduating and they probably wouldn't want to, you know, yeah, be – be friends with me, be with me any longer so, yeah. (Hayden)

Theme 3 – navigating adult roles and relationships

Importance of parental agency and advocacy in accessing funds and services

Parents were commonly mentioned by participants as being important in transition planning, and in advocating for them in accessing funding and services, but equally were seen as rule setters for young people who were living with them several years after leaving school. Accessing disability services beyond school and obtaining sufficient funding through the NDIS was a frustrating process for participants who relied on their capacity to advocate for themselves or having support from a family member or other support person who was able to advocate on their behalf and “speak the right language.” Paul referred to navigating the NDIS as being like “just trying to bark correctly.” He lamented that to get funding to support goals and needs, you had to meet strict criteria, be assertive and use the correct terminology for funded items:

You have to like, you know, bark for it beforehand. So, basically, you will be barking, you know, constantly at them to try and get something out of them … NDIA are basically just saying to all the participants … You want in; bark [like a dog] (Paul).

Parent protection, rules and demands

Many of the participants in this study still lived with their parents, including individuals who had been out of school for a decade. While some participants were content with living with their parents, others spoke of tense or difficult relationships with their parents around decision making. Christina was upset with her mother for denying her the opportunity to go on a camp organised by the disability service for the clients. She emphatically stated, “I hate my mum,” indicating that this choice should be her own as an adult. Paul explained how he frequently argued with his parents to assert his opinions:

We have a discussion with me and my parents … we always end up in an argument. So me and my parents eventually after about – I don't know – about six or seven years of arguing and whatnot and fighting constantly, seeing who can get the last word, because I always stand up for myself constantly because that's, you know, when we're always fighting I always stand up for myself all the time. (Paul)

Jack explained that his mother disagreed with his choice of career and the people he wanted to spend time with. He talked about his keen interest in making YouTube movies and posting them online. This was something that he spent a lot of time doing, and wanted to pursue as a job, but his mother did not agree with this ambition as a real job: “mum noticed that YouTube is not a job, and I watch YouTube clips … YouTube is a job job and you get paid. You get paid – it pays … .”

Jack had also wanted to catch up with some friends from school but explained that his mother did not approve of them: “I got friends from school I want to connect to … it’s pretty hard because mum doesn’t want me to go outside and hang out with my old friends.”

Longing for intimate relationships and a family of their own

Many participants described desires for intimate relationships, finding a partner, and having families of their own, feeling desperately left behind when siblings achieved these milestones. Two of the older participants talked with longing about having a family to find that real sense of purpose in life. For example, for Nick the goal of having a family was a “real thing,” that he told us was wanted by “lots of people.” He described a sense of being left behind by siblings and cousins experiencing these milestones: “they're all getting married one by one, by one … And starting a family.”

Similarly, Aisha also told us that her biggest wish was to raise her own family. When looking at family members achieving these milestones, Aisha felt that she was missing out:

My cousins and all that got married and that … And, like, they got a family now with kids and that … And I can see it, and I'm – I'm saying – I'm saying to myself – I'm – I'm, like a bit behind them. Like, one day I’ll try to hopefully raise a family. (Aisha)

Um, so I got a girlfriend from high school and her – she’s nice to me. Her name’s [Girlfriend] and she kissed me a million times and her brother come along and tried to threat [sic] me, like to … like to have a fight or something … now she’s at a different school so I don’t see her anymore, but I want to see her. (Jack)

Discussion

Our study reinforces and broadens what is known about the challenges facing young people with intellectual disability during their transition to adulthood because it presents the views and experiences of young people themselves rather than those of their parents and other proxies (Young-Southward et al., Citation2017). The young people in our study often felt excluded from decision-making about their lives, especially during transition planning at school, but also in the NDIS planning process, and after transitioning into post-school disability services. After leaving the school structure that had long regulated their lives and set expectations of their role as students, many participants felt lost and uncertain about their adult role and identity. Most continued to search for meaning and purpose in their lives as they experienced missing out on typical young adult milestones such as post-school education, employment, intimate relationships, and raising a family of their own.

Positive experiences with post-school transition were rare for our participants. Good planning and coordination were usually the work of a committed teacher or careers advisor, but more commonly family, particularly mothers, advocated for transition plans and activities. These reported experiences reflect findings in previous research on transition, but contrast sharply with the NDIS’ promise to provide “choice and control.”

Accessing NDIS funding to support transition and services, depends largely on the capacity to advocate for self, or the ability and energy of families to navigate a complex funding and service system. For this reason, Bigby (Citation2020) has argued that the original design of the NDIS is poorly suited to people with intellectual disability and individualised funding schemes. Without a formal structure to support decision-making processes by people with intellectual disability, there is a real risk that they will have little input into planning and, as a consequence, experience poorer post-school outcomes compared to other groups (Bigby, Citation2020; Collings et al., Citation2019).

The recently published guidelines in Australia’s Disability Strategy 2021–2031 (Australian Government, December Citation2021) and best practice guidelines (Kohler et al., Citation2016; Papay & Bambara, Citation2014) stipulate a structured, student-focused process and development, with interagency collaboration and family engagement. Nationally consistent transition policies are needed based on these guidelines, with an emphasis on a more person-centred and collaborative approach. We argue that for such policies to be effective, they must be underpinned by an accountability framework with timelines for implementation and named responsible roles for transition planning processes. Longitudinal research, more extensively co-designed with consumers and advocates, would help to understand the impact of early planning and intervention such as work experience and training, along with support services, and family advocacy.

There was a shared sense among participants that most disability services did not prioritise activities that were supportive in reaching their goals. This was especially related to support with finding and keeping paid employment, even in services that had been contracted to do so. Our participants lamented that they were repeatedly offered the same limited activities with few opportunities for growth and development. These sentiments reflect recent findings in the NDIS School leaver participant survey report (National Disability Insurance Agency, Citation2022b), suggesting that respondents found providers to spend insufficient time identifying and understanding their work goals, arranging work experience, and providing skill building opportunities (p. 17).

Several participants expressed frustrations with being stuck with a life in disability services and locked into the role of “disability person.” Wanting to do and be more, they had moved between services in search of meaning and purpose, effectively prolonging their transition. Midjo (Citation2018) suggest that this sense of perpetual transition happens because of conflicting beliefs and values between young people who expect to take on adult roles after leaving school, and disability service providers who see these young people as service receivers. Through standardised information and assessments, they argue, “the voices of young adults are transformed into a process where the professionals are producing young adults with standardized needs that fit an institutional variation of offers,” which in turn may produce “institutional identities” (Midjo, Citation2018).

Future research needs to explore more systematically whether, and how effectively, disability day services meet the intended expectations of their clients, and what the outcomes are of their services. Individual and specific outcomes of transition planning and strategies under the NDIS must also be explored more systematically.

Leaving school means losing connections with friends and other social networks. For our participants, social life was largely limited to interactions with family, service providers, and other consumers in the same service with little effort by providers to support wider opportunities for social engagements and fostering friendships. Without having a meaningful role, a negative self-concept may enforce a sense of isolation and loneliness that can impact young people’s health and wellbeing significantly (Salt, Citation2019). Transition and service plans must include strategies for fostering social identities through friendships, casual employment, intimate relationships, parenting, or caring for others. Service providers can play an important role in supporting young people with intellectual disability through communication skills training and bringing individuals together to foster friendships and create opportunities for normative social roles (Garolera et al., Citation2021). Lloyd et al. (Citation2022) argue that positioning individuals as “disabled” “without any other identities or social roles, a number of damaging consequences may result” (p. 2). These include low expectations and limited provision of opportunities to young people with intellectual disability by which they bypass many experiences taken for granted by young people without intellectual disability.

For young people who continue to live in the family home, adopting a suitable adult identity may be contentious. Indeed, many participants talked about frictions in negotiating adult roles with their parents. Parents were often described by participant as their strongest advocates, but also referred to as (over) protectors, gate keepers, and rule setters. Such tensions may make young adults feel stuck perpetually in a stage of “emerging adulthood”(Pearson et al., Citation2021) often without the autonomy and role identity that adults without disability typically develop through leaving the family home, and engaging in training, employment, and intimate relationships.

Strengths and limitations

In this paper we presented the voices and experiences of 27 young people with intellectual disability living in five Australian states, which provide confidence in the qualitative findings. Our study was co-designed meaning our interview questions reflected the concerns of young people with intellectual disability on our advisory group. We acknowledge the absence of young people with severe and profound intellectual disability as a limitation. Their transition experiences were predominantly facilitated by parent carers and will be reported with parent experiences in a forthcoming article. Future research should prioritise the experiences of young people with more severe cognitive and communication difficulties, also from geographically isolated and linguistically and culturally diverse families.

Most participants in this study were engaged in post-school disability services and the experience might have been different for young people not accessing services. Some of the staff present at interviews and focus groups were involved in current post-school service provision, but not transition planning. Their presence is a possible limitation of the study, however young people mostly provided candid responses, including adverse comments about their support service or frustration about things not working out as they had hoped. We also note that some young people’s experiences with disability services during the time of data collection were influenced by reduced activities due to government-imposed lockdowns and restrictions during the coronavirus pandemic.

Conclusion

Transition from school policies and the NDIS are in place to support and empower young people with disability to live purposeful lives. However, for many young people with intellectual disability and their families the idea of choice and control is far from reality, with significant transition challenges remaining. There has been minimal change in transition from school experiences despite decades of research and calls for change to practice. Many young people with intellectual disability are still excluded from having agency and experiencing meaningful adult lives after leaving school. Essentially a welfare model of disability persists, relying extensively on parent or carer intervention and day service funding. We suggest that a nationally consistent and accountable transition strategy is needed to support young people with intellectual disability to become valued citizens, contributing purposefully to their communities and achieving their goals for adulthood. A systematic and multifaceted approach is required to address identified policy, system, and service gaps alongside considerations for more effective NDIS processes, funding, and supports.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the young people who participated in this study who so generously shared their experiences.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Technical and further education (TAFE) is a vocational training provider run by each state government in Australia. Vocational education and training is study that offers opportunities to learn specific and practical job skills. https://www.futurityinvest.com.au/insights/futurity-blog/2022/03/30/tafe-or-uni

References

- Ashburner, J. K., Bobir, N. I., & van Dooren, K. (2018). Evaluation of an innovative interest-based post-school transition programme for young people with autism spectrum disorder. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education, 65(3), 262–285. https://doi.org/10.1080/1034912X.2017.1403012

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2020, July 24). Disability and the labour force. Australian Bureau of Statistics. Retrieved June 16 from https://www.abs.gov.au/articles/disability-and-labour-force

- Australian Government. (2021, December). Australia's disability strategy 2021-2031 - outcomes framework. Comonwealth of Australia. https://www.disabilitygateway.gov.au/ads

- Australian Parliament. (2017). The national disability insurance scheme: A quick guide. Australian Parliament. https://www.aph.gov.au/About_Parliament/Parliamentary_Departments/Parliamentary_Library/pubs/rp/rp1617/Quick_Guides/NDIS

- Bennett, S., Gallagher, T., Shuttleworth, M., Somma, M., & White, R. (2017). Teen dreams: Voices of students with intellectual disabilities. Journal of Developmetal Disabilities, 23(1), 64–75. Retrieved from https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/teen-dreams-voices-students-with-intellectual/docview/1991893701/se-2.

- Bigby, C. (2020). Dedifferentiation and people with intellectual disabilities in the Australian national disability insurance scheme: Bringing research, politics and policy together. Journal of Intellectual & Developmental Disability, 45(4), 309–319. https://doi.org/10.3109/13668250.2020.1776852

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2019). Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 11(4), 589–597. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2019.1628806

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2021). One size fits all? What counts as quality practice in (reflexive) thematic analysis? Qualitative Research in Psychology, 18(3), 328–352. https://doi.org/10.1080/14780887.2020.1769238

- Collings, S., Dew, A., & Dowse, L. (2019). “They need to be able to have walked in our shoes”: What people with intellectual disability say about National Disability Insurance Scheme planning. Journal of Intellectual & Developmental Disability, 44(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.3109/13668250.2017.1287887

- Council of Australian Governments. (2018). National School Reform Agreement. https://federalfinancialrelations.gov.au/sites/federalfinancialrelations.gov.au/files/2021-07/national_school_reform_agreement_8.pdf

- Dyke, P., Bourke, J., Llewellyn, G., & Leonard, H. (2013). The experiences of mothers of young adults with an intellectual disability transitioning from secondary school to adult life. Journal of Intellectual & Developmental Disability, 38(2), 149–162. https://doi.org/10.3109/13668250.2013.789099

- Foley, K.-R., Dyke, P., Girdler, S., Bourke, J., & Leonard, H. (2012). Young adults with intellectual disability transitioning from school to post-school: A literature review framed within the ICF. Disability and Rehabilitation, 34(20), 1747–1764. https://doi.org/10.3109/09638288.2012.660603

- Foley, K.-R., Jacoby, P., Girdler, S., Bourke, J., Pikora, T., Lennox, N., Einfeld, S., Llewellyn, G., Parmenter, T. R., & Leonard, H. (2013). Functioning and post-school transition outcomes for young people with down syndrome. Child: Care, Health and Development, 39(6), 789–800. https://doi.org/10.1111/cch.12019

- Garolera, G. D., Díaz, M. P., & Noell, J. F. (2021). Friendship barriers and supports: Thoughts of young people with intellectual disabilities. Journal of Youth Studies, 24(6), 815–833. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676261.2020.1772464

- Gauthier-Boudreault, C., Gallagher, F., & Couture, M. (2017). Specific needs of families of young adults with profound intellectual disability during and after transition to adulthood: What are we missing? Research in Developmental Disabilities, 66, 16–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2017.05.001

- Hudson, B. (2003). From adolescence to young adulthood: The partnership challenge for learning disability services in England. Disability & Society, 18(2), 259–276. https://doi.org/10.1080/0968759032000052851

- Hughes, J., Davies, S., Chester, H., Clarkson, P., Stewart, K., & Challis, D. (2018). Learning disability services: User views on transition planning. Tizard Learning Disability Review, 23(3), 150–158. https://doi.org/10.1108/TLDR-07-2017-0032

- Jacobs, P., MacMahon, K., & Quayle, E. (2018). Who decides? - Transition from school to adult services for young people with severe or profound intellectual disability: A systematic review utilizing framework synthesis [review]. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 31(6), 962–982. https://doi.org/10.1111/jar.12466

- Kohler, P. D., Gothberg, J. E., Fowler, C., & Coyle, J. (2016). Taxonomy for transition programming 2.0. Western Michigan University.

- Lawson, K., & Parker, R. (2020). How do young people with education, health and care plans make sense of relationships during transition to further education and how might this help to prepare them for adulthood? Educational and Child Psychology, 37(2), 48–58. https://doi.org/10.53841/bpsecp.2020.37.2.48

- Leonard, H., Foley, K., Pikora, T., Bourke, J., Wong, K., McPherson, L., Lennox, N., & Downs, J. (2016). Transition to adulthood for young people with intellectual disability: The experiences of their families. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 25(12), 1369–1381. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-016-0853-2

- Lloyd, J., Moni, K., Cuskelly, M., & Jobling, A. (2022). The national disability insurance scheme: Voices of adults with intellectual disabilities. Research and Practice in Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 9(1), 5–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/23297018.2021.2004382.

- Mazzotti, V. L., Rowe, D. A., Kwiatek, S., Voggt, A., Chang, W.-H., Fowler, C. H., Poppen, M., Sinclair, J., & Test, D. W. (2021). Secondary transition predictors of postschool success: An update to the research base. Career Development and Transition for Exceptional Individuals, 44(1), 47–64. https://doi.org/10.1177/2165143420959793

- Meadows, D., Davies, M., & Beamish, W. (2014). Teacher control over interagency collaboration: A roadblock for effective transitioning of youth with disabilities. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education, 61(4), 332–345. https://doi.org/10.1080/1034912X.2014.955788

- Meltzer, A., Robinson, S., & Fisher, K. R. (2020). Barriers to finding and maintaining open employment for people with intellectual disability in Australia. Social Policy & Administration, 54(1), 88–101. https://doi.org/10.1111/spol.12523

- Midjo, T. (2018). Identity constructions and transition to adulthood for young people with mild intellectual disabilities. Journal of Intellectual Disabilities, 22(1), 33–48. https://doi.org/10.1177/1744629516674066

- National Disability Insurance Agency. (2022a). NDIS participant employment strategy. https://www.ndis.gov.au/about-us/strategies/participant-employment-strategy#employment

- National Disability Insurance Agency. (2022b). School leaver participant survey report. NDIS, Market Innovation & Employment Branch. https://www.ndis.gov.au/participants/finding-keeping-and-changing-jobs/leaving-school#school-leaver-participant-survey-report

- NSW Government. (2016, 15.07.2021). Transition planning. NSW Government. Retrieved 20.10 from https://education.nsw.gov.au/teaching-and-learning/disability-learning-and-support/leaving-school/transition-planning

- NSW Government. (2019). Transition planning for school leavers in 2019. Resources to support collaborative planning in schools. NSW Government.

- Papay, C. K., & Bambara, L. M. (2014). Best practices in transition to adult life for youth with intellectual disabilities. Career Development and Transition for Exceptional Individuals, 37(3), 136–148. https://doi.org/10.1177/2165143413486693

- Pearson, C., Watson, N., Gangneaux, J., & Norberg, I. (2021). Transition to where and what? Exploring experience of transition to adulthood for young disabled people. Journal of Youth Studies, 24(10), 1291–1307. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676261.2020.1820972

- Queensland Government. (2021). Transition to post-school for students with disability: Fact sheet for students and parents/carers. https://education.qld.gov.au/student/students-with-disability/supports-for-students-with-disability/Documents/transition-to-post-school.pdf

- Redgrove, F. J., Jewell, P., & Ellison, C. (2016). Mind the gap between school and adulthood for people with intellectual disabilities. Research and Practice in Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 3(2), 182–190. https://doi.org/10.1080/23297018.2016.1188671

- Salt, E. (2019). Transitioning to adulthood with a mild intellectual disability - Young people’s experiences, expectations and aspirations. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 32(4), 901–912. https://doi.org/10.1111/jar.12582

- Smith, L., & Dowse, L. (2019). Times during transition for young people with complex support needs: Entangled critical moments, static liminal periods and contingent meaning making times. Journal of Youth Studies, 22(10), 1327–1344. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676261.2019.1575346

- Young-Southward, G., Cooper, S.-A., & Philo, C. (2017). Health and wellbeing during transition to adulthood for young people with intellectual disabilities: A qualitative study. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 70, 94–103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2017.09.003

- Zhou, Q., Llewellyn, G., Stancliffe, R., & Fortune, N. (2019). Working-age people with disability and labour force participation: Geographic variations in Australia. Australian Journal of Social Issues, 54(3), 323–340. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajs4.75