ABSTRACT

Adult siblings without disabilities play important roles in relation to their brothers and sisters with intellectual disabilities. This study reviewed knowledge about adult sibling relationships in Chinese societies, where one sibling has intellectual disability. Five English and two Chinese databases were searched for publications published up to 2022. Findings, based on 14 identified articles show that sibling relationships are considered in the context of parent-child relationships. Little attention is given to the nature of sibling relationships per se. Rather, research in Chinese societies generally frames sibling relationships as one-way caregiving, and where siblings’ caregiving responsibilities are inherited from parents, increase as parents age and are organised according to gender and birth order. These findings contrast to Western studies where increasingly perspectives of adults with intellectual disabilities are sought and the reciprocal nature of sibling relationships is highlighted. Future research in Chinese societies may benefit from exploring aspects of relationships beyond caregiving.

Familism is a fundamental ideology in Chinese Confucian culture. It emphasises familial cohesiveness and prioritises familial over individual interests (Liu, Citation2011; Yan, Citation2018). The individual is relational and interdependent. Familism values individual obligations and self-sacrifice (Garzón, Citation2000) as family members are expected to take care of each other (Cheung, Citation2015) and to express gratitude for the care they receive (Fan, Citation2007).

An individual in a Chinese family is situated at the centre of a kinship network, created through marriage and procreation. Each kin relationship has a differing set of rights and obligations (Fei, Citation1992) often determined by generation and gender (Yan, Citation2018). Parent–child and marital relationships are the strongest and carry the most obligations. Parent–child relationships are represented as Shang–Xia (superior–subordinate). They are unequal as children are expected to obey and meet parental ambitions for them but also reciprocal, as parents are obligated to raise and educate their children (Kuo & Geraci, Citation2012). In return, children in later life observe filial piety in caring for their parents, providing financial support and satisfying parents’ expectations (Chen et al., Citation2016). Similarly, traditional gender roles expect that women take responsibility for domestic tasks and obey their husbands, who in turn take on the role of financially supporting the family (Luo & Chui, Citation2018).

In Chinese societies, individuals with intellectual disabilities are commonly perceived as vulnerable, having low status and contributing less to the family than other members (Deng et al., Citation2001). When one member has intellectual disability, the family unit provides the lifelong care that member requires (Holroyd, Citation2003). In this context “care” has a broad meaning and is likely to encompass accommodation, personal care, financial and everyday support, as well as supervision and decision making. In the past, the stigma associated with having a child with intellectual disability in Chinese societies meant that many families took care of their relatives with intellectual disabilities at home, keeping their disability a secret to avoid losing “face” (reputation) (Chen & Yu, Citation2023). For example, if parents required additional help, they were more likely to seek assistance from close relatives than from outsiders or formal services (Chien & Lee, Citation2013).

The negative consequences of long-term caregiving for a family member with disability have been a dominant theme in research conducted in Chinese cultures. For example, studies have identified long-term caregiving as leading to financial strain, poor social networks, physical and emotional health problems (Hu et al., Citation2012; Pan & Ye, Citation2015; Yang et al., Citation2016). Research also suggests caregiving has a negative impact on educational attainment and careers, particularly for mothers who undertake the bulk of caregiving work (Chou et al., Citation2018a). Some parents also internalise the disability-specific stigma they experience which has been found to lead to psychological distress (Chiu et al., Citation2013; Yang, Citation2015).

During the last 20 years, the increased longevity of adults with intellectual disabilities and their parents’ ageing has highlighted the potentially important role of siblings (Chou & Kröger, Citation2020; Liang, Citation2021; Rehabilitation Advisory Committee (RAC), Citation2016). Few adults with intellectual disabilities have spouses or children. Siblings typically have longer-lasting kin relationships, therefore are likely to be important to family stability and functioning, especially when parents can no longer provide care (Liang, Citation2021). Warm relationships between siblings may contribute to the quality of life of adults with intellectual disabilities (Liang, Citation2021).

The impact of policies designed to restrict or encourage childbirth has meant that there is a high chance that an individual with intellectual disability will have a sibling. During the one-child policy period in mainland China, for example, a couple whose first child had disability was permitted to have a second child (Liang, Citation2015). Currently, in most Chinese societies, governments encourage the birth of multiple children (Kim et al., Citation2020).

International literature reviews that focus on the siblings of adults with intellectual disabilities illustrate that research about this topic covers a broad range of areas, including psychological outcomes, life choices, relationships, sibling roles, caregiving, quality of life, and future planning (Davys et al., Citation2011; Heller & Arnold, Citation2010; Lee & Burke, Citation2018, Citation2020; Múries-Cantán et al., Citation2022). Literature reviews, such as these, have found that adult siblings report positive and negative impacts of having a sibling with intellectual disability. Positive impacts include emotional closeness, good health and a sense of reward, while negative impacts include a burden of responsibility for providing care, a lack of attention from parents, and family distress. Siblings without disabilities are also likely to take on caregiving responsibilities for their brothers or sisters with intellectual disabilities in the future when their parents are no longer able to do so. Research suggests that factors such as high parental expectations, being female, positive family relationships, and open discussion about the future may predict greater involvement in future caregiving by a sibling (Davys et al., Citation2011).

Research about the roles of the siblings of adults with intellectual disabilities has been dominated by Western Caucasian cultural perspectives (Davys et al., Citation2011) where individualism is often stronger than the familism and filial piety characteristic of Chinese societies. Chinese societies offer a different socio-cultural context in which to explore the roles and experiences of siblings of adults with intellectual disabilities (Chiu, Citation2021) which has seldom been explored. This scoping review aimed to fill this gap in the literature by addressing the research question: what is the current state of knowledge about adult sibling relationships in Chinese societies where one has intellectual disability?

Method

This scoping review followed the five-stage approach proposed by Arksey and O’Malley (Citation2005). We searched five English and two Chinese language databases to find literature about the adult sibling relationships in Chinese societies where one had intellectual disability. The English databases were Medline, Scopus, PsycInfo, ProQuest, and Cinahl. The Chinese databases were the Chinese National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI) in mainland China and the Airiti Library in Taiwan. These are the most comprehensive search engines in mainland China and Taiwan. Neither Hong Kong nor Macao have Chinese language databases.

For the searches of English databases, the search terms with Boolean operators comprised three groups of words: intellectual disability, sibling, and location. For instance, one search was conducted for “ “learning disability” AND sister* AND China.” Group one included intellectual disability, mental retardation, mental handicap, learning disability, cognitive disability, developmental disability, autism, cerebral palsy, down syndrome, intellectual and developmental disability, and intellectual development disorder. We included autism and cerebral palsy because of their high co-morbidity with intellectual disability. The second group of terms contained sibling, brother and sister. The locations of studies included mainland China, Taiwan, Macao, and Hong Kong. In these four geographical regions, over 90% of residents are identified as ethnically Chinese and people share a common Chinese cultural background (Lo, Citation2016).

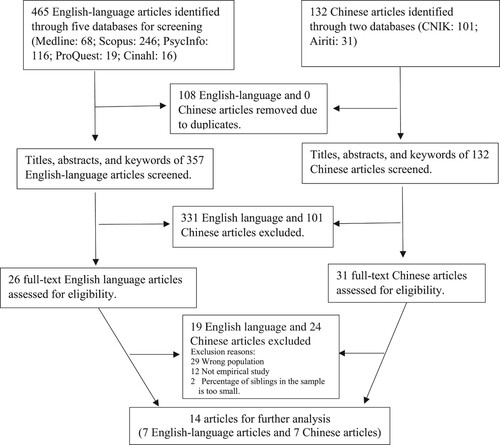

To search the Chinese databases, the first two groups of search terms were translated into Chinese. The Chinese phrases were adjusted and expanded according to customary expressions in the local Chinese cultural context. We did not use the terms relating to location because very few Chinese articles include international locations. The inclusion criteria are shown in . We did not set the starting date of the search period but limited the end year to 2022. Given changes across the life course in sibling relationships, this review focuses on sibling relationships in adulthood. We did not only include the viewpoints of siblings without disabilities but also incorporated the perspectives of parents and siblings-in-law about these relationships as they offer valuable insights into these.

Table 1. Inclusion criteria.

Screening process

The search was conducted in October 2022. shows the process for the selection of articles. A total of 440 English-language articles and 130 Chinese articles were initially identified. The first author examined the title, abstract, and keywords and removed articles that did not meet the inclusion criteria. Where there was uncertainty about inclusion of an article, the views of the other two authors were sought and a consensus reached. After exclusions, 26 English-language and 31 Chinese articles remained. After reading the full texts of these articles, a further 19 English-language and 24 Chinese articles were excluded. Finally, seven English-language and seven Chinese articles were left for analysis.

Data extraction and analysis

The authors imported all articles to Nvivo 12 to extract data for analysis. Key information, including author, year of publication, research aims and questions, method, number of participants and main findings, were extracted and are summarised in . All the authors read the included articles and together discussed their preliminary thoughts about themes, which were refined further by the first author. Four rounds of discussion and refinement of the themes occurred until the authors reached a consensus on the four themes presented in the findings.

Table 2. Characteristics of the extracted studies.

Findings

The small number of included articles that concern the study of adult siblings where one has intellectual disability suggest that this is an emerging research area in Chinese societies. A total of 14 articles were published up to 2022. Most of these were published after 2011 (12), with just over half of those published in the last 3 years (7). The 14 articles were based on 13 studies, most of which had been conducted in Taiwan (10), with three in mainland China and one in Hong Kong.

The research reported in a majority of articles (11) used qualitative methodologies with small samples, and methods such as critical autobiography, phenomenology, and ethnography. Most studies used in-depth interviews with siblings without disabilities, siblings-in-law, or parents to explore siblings’ experiences, relationships, and perceptions by others about their roles. Three articles used quantitative methodologies, reporting results of surveys using validated measures. None of the studies collected data from the siblings with intellectual disabilities nor sought information about their experiences from the other respondents.

Of the articles examined, 11 of the 14 situated siblings’ experiences firmly within the context of the family and parent-child relationships, with caregiving by siblings as the central theme. Only Liang’s (Citation2021, Citation2023) study focused more specifically on the nature of the relationship between sibling. Li (Citation2006)’s study was solely concerned with the self-advocacy of siblings without disabilities and Liu et al. (Citation2020) examined the influence of having a sibling with intellectual disability on vocational choices among special school teachers.

Caregiving as one-way giving

Siblings’ roles were conceived as a part of family caregiving which was a central theme of most studies and framed as a one-way rather than reciprocal process (e.g., Chen, Citation2011; Lu et al., Citation2008). In these studies, siblings with intellectual disabilities were represented as vulnerable and requiring care, which was seen to be the shared responsibility of other family members to provide. No studies addressed the obligations of siblings with intellectual disabilities towards their families.

Having a sibling with intellectual disability and one-way caregiving were represented as unrewarding and negatively impacting siblings’ lives. For example, Liang (Citation2023) found that siblings without disabilities experienced a sense of affiliate stigma which negatively affected their relationship with their siblings with intellectual disabilities. Pan and Ye (Citation2015) found that siblings without disabilities were more likely to be turned down by potential spouses who perceived marriage would entail sharing their spouses’ caregiving responsibilities for their brothers or sisters with intellectual disabilities. Nevertheless, two studies identified positive factors, and these included having opportunities to learn disability-specific knowledge and improving siblings' empathy and motivation to help other families with similar needs (Liu et al., Citation2020; Yan & Chang, Citation2021).

Caregiving as intergenerational inheritance

Five studies considered siblings’ caregiving responsibilities increased as parents aged, and as something they inherited from their parents (e.g., Fan & Chen, Citation2022). Chiu (Citation2021) explored how siblings’ caregiving roles changed during adulthood. Caregiving was perceived as minimal in young adulthood, when their parents were healthy and provided most care (Chiu, Citation2021; Yan & Chang, Citation2021). It was shared with their parents in middle adulthood and then gradually siblings became primary caregivers in mid to late adulthood as parents aged, became frail or died (e.g., Pan & Ye, Citation2015; Chou et al., Citation2018b). Likewise, Liang (Citation2021) found that the older the siblings were, the higher their motivation to take care of their siblings with intellectual disabilities. However, there were no studies exploring siblings’ roles as primary caregivers after their parents had died.

Many of the studies found parents had an implicit, unspoken expectation about the transfer of care to their offspring without disabilities (e.g., Chou et al., Citation2018b; Kuo, Citation2015). Chiu (Citation2021) found that vague or unspoken plans caused anxiety for siblings without disabilities who felt obliged by filial piety to satisfy their parents’ expectations.

Two studies attributed the long-term involvement of siblings without disabilities in caregiving for their brothers and sisters with intellectual disabilities to filial piety owed to their parents (Chen, Citation2011; Chiu, Citation2021). In these cases, siblings without disabilities were concerned about their parents’ physical and emotional fatigue and on their parents’ instructions assumed primary caregiving responsibility when their parents were still alive (Chen, Citation2011; Chiu, Citation2021).

Caregiving as a source of intergenerational tension

The care that many parents and siblings provided for their adult relatives with intellectual disabilities could be a source of intergenerational tension. Four articles attributed intergenerational tension in the young adulthood years to the unequal treatment by parents who placed their adult child with intellectual disability at the centre of the family (e.g., Yan & Chang, Citation2021). In these articles, young adult siblings without disabilities were expected to act as role models, perform well, and protect their siblings with intellectual disabilities. Their additional family responsibilities were perceived as restrictive by young adults who wanted to be independent of their families of origin and for some led to resentment of their parents and their siblings with intellectual disabilities (Fan & Chen, Citation2022).

Some studies found that in middle and late adulthood, siblings increased their caregiving but did so alongside their parents who were reluctant to withdraw from caregiving despite their reduced functional capacity (e.g., Chiu, Citation2021; Kuo, Citation2014). This co-caring led to tensions as the approaches of different generations clashed (Chiu, Citation2021). Kuo (Citation2015) found that intergenerational tensions most commonly occurred between mothers and their daughters-in-law (who were sisters-in-law of the adults with intellectual disabilities). Conflict occurred when the younger women challenged what they saw as the mothers’ overprotective parenting and tried to take a more proactive role in developing the independence skills of the adults with intellectual disabilities. Two studies found that such disagreements about styles of caregiving were mediated by fathers or sons from whom sisters-in-law sought assistance (Chen, Citation2011; Kuo, Citation2015).

Caregiving as division of labour based on gender and birth order

Studies revealed that expected caregiving roles of siblings of adults with intellectual disabilities were based on gender norms and birth order (e.g., Fan & Chen, Citation2022; Pan & Ye, Citation2015). Many studies found that responsibility for caregiving and the direct provision of care were separated, and male siblings were expected to take caregiving responsibility (e.g., Kuo, Citation2014). Direct care work was mainly done by women, including mothers, sisters-in-law, and sisters (e.g., Kuo, Citation2015). The specific work that sisters or sisters-in-law performed included communication, protection from harm and housework, such as cleaning (e.g., Li, Citation2006). Two studies revealed the unequal rights of brothers and sisters without disabilities reflecting their differing family obligations, noting that brothers who took on greater responsibilities were to be prioritised in the distribution of family wealth when parents died (Chiu, Citation2021; Kuo, Citation2014).

Expectations of siblings were also moderated by their birth order, with greater responsibility falling to older siblings (e.g., Fan & Chen, Citation2022). When there was more than one brother without disabilities, the eldest brother was expected to take on responsibility for caregiving and economic wellbeing (e.g., Kuo, Citation2014, Citation2015). When there were no brothers without disabilities, sisters were expected to fulfil this male responsibility (Pan & Ye, Citation2015) and the eldest sister to take responsibility when there are two or more sisters without disabilities.

The gendered division of labour influenced the stress associated with caregiving. Kuo (Citation2014) found that brothers felt anxious because they were unfamiliar with direct caregiving roles and lacked adequate caregiving skills. In contrast, sisters-in-law experienced fatigue because they undertook a large amount of direct care work (Kuo, Citation2015).

Discussion

This scoping review, exploring knowledge about adult sibling relationships in Chinese societies where one has intellectual disability, identified 14 articles up to 2022. A strength of the review is the inclusion of literature published in the Chinese language. The small body of work identified contrasts to the larger and more mature body of research about relationships between adult siblings with and without intellectual disabilities in Western societies. For example, Heller and Arnold’s (Citation2010) review of relationships between adult siblings where one had intellectual disability identified 21 articles, 13 published during the 1990s and 8 in the 2000s. Lee and Burke’s (Citation2018) review of caregiving roles undertaken by siblings for their brothers or sisters with intellectual disabilities identified a further 29 studies, 4 published before 2000, 9 in the 2000s, and 16 after 2010. By contrast, of these 14 articles that focussed on Chinese societies, 12 were published after 2010, indicating a significant lag in this research area.

The studies in this review primarily focused on responsibilities for caregiving, which were shared by parents and their offspring without disabilities. The intergenerational dynamics found in this review suggest that in Chinese societies, the relationship between adult siblings with and without intellectual disabilities are firmly situated in the context of parent–child relationships. None of these studies identified any expectations that adults with intellectual disabilities should assume family obligations within their families, which is indicative of their devalued status within families. This attribution of lower status to a person with intellectual disability reflects findings of other studies of Chinese families, in which for example, the family member with intellectual disability is seen as a “forever child” (Xun & Cui, Citation2022) and as having few rights and responsibilities (Qu, Citation2020). The agency of people with developmental disabilities was not fully addressed in Chinese disability research (Qian, Citation2022).

None of the Chinese studies sought the perspective of the adults with intellectual disabilities themselves or explored the nature of their relationship with their siblings. This contrasts with studies of sibling relationships in Western societies which are increasingly seeking the perspectives of adults with intellectual disabilities (Burbidge & Minnes, Citation2014; Meltzer, Citation2018) and exploring their relationships with their adult siblings (Avieli et al., Citation2019; Dew, Citation2010; Meltzer, Citation2018).

Despite these differences in the focus of research about siblings between Chinese and Western societies, in both types of society some parents expect that siblings will take on caregiving responsibilities for their brothers or sisters with intellectual disabilities as they get older (Avieli, Citation2020; Chiu, Citation2021). Studies from both societies also identify that parents are often unwilling to discuss plans for the future care of their adult child with intellectual disability but have implicit plans and unspoken expectations about roles siblings might take (Chiu, Citation2021; Lee & Burke, Citation2020). Studies also suggest tensions are found in both types of society between adult siblings without disabilities and their parents, particularly with respect to mothers’ protective caregiving for their adult child with intellectual disability (Davys et al., Citation2015; Kuo & Geraci, Citation2012). In the Chinese context, the sister in laws’ actions offended their mothers and were considered disrespectful according to the Confucian ethos, Shang–Xia (superior-subordinate) (Kuo & Geraci, Citation2012).

The strong sense of responsibility for caregiving felt by siblings without disabilities in Chinese societies (Kuo, Citation2014; Pan & Ye, Citation2015) may be driven by filial piety (Kuo & Geraci, Citation2012). In contrast, research suggests there is less consistency in the responsibility for caregiving felt by siblings in Western societies where the concept to filial piety holds less sway. For example, studies have found that less than half of siblings interviewed intended to take on primary caregiving responsibility when their parents could no longer provide care (Bigby, Citation1997; Griffiths & Unger, Citation1994). Rather research in Western societies has found adults have various types of relationships with their siblings with intellectual disabilities, including parent-surrogate, the estranged, the bystander, the mediator, and the friend (Avieli et al., Citation2019).

Both Chinese and Western literature show that female siblings are more involved in direct caregiving or had closer relationships with their siblings with intellectual disabilities (Chiu, Citation2021; Kuo, Citation2014; Orsmond & Seltzer, Citation2000). However, in Chinese societies, siblings’ involvement in caregiving may be based on a more rigid and relatively fixed division based on gender and birth order (Fan & Chen, Citation2022) compared to Western societies (Bigby, Citation1997; Orsmond & Seltzer, Citation2000).

The strong sense of responsibility in Chinese societies felt by siblings to be involved in caregiving for their brothers or sisters with intellectual disabilities may safeguard their siblings’ basic human needs and help to satisfy psychological needs arising from an internalised ethic of care that priorities family responsibility (Fu et al., Citation2020; Huang & Fiocco, Citation2020). However, the long-term caregiving burden borne by siblings may also be accompanied by affiliate stigma and bring few other rewards. The extent to which these factors may impact on the quality of their caregiving or relationships with their siblings with intellectual disabilities remains unexplored. At a broader level, cultural expectations of siblings’ involvement in caregiving free the government from taking full responsibility for adults with intellectual disabilities.

Limitations

This scoping review offers a unique perspective on the sibling relationships of adults with intellectual disabilities in Chinese societies. However there are several limitations. First, the review only included empirical studies published in academic journals and excluded theoretical articles, policy analyses, dissertations, and grey literature, which may have provided other perspectives on this topic which might explain why the absence of papers on aspects of sibling relationships other than caregiving. Second, most of the research reported in the included articles was conducted in Taiwan, with less research conducted in mainland China and Hong Kong. In particular, very few studies had been conducted in the remote, rural, and ethnic minority areas, where a high proportion of people with disabilities in mainland China reside (Yang, Citation2012). As a result, the review may not reflect the diversity of understanding about adult sibling relationships where one has intellectual disability in Chinese societies.

Conclusion and implications

This review summarises the current state of research about siblings of adults with intellectual disabilities in context of Chinese societies, primarily Taiwan, filling a gap in the international literature. Research on this topic is only just emerging and is largely one-dimensional focusing on siblings within the context of family caregiving responsibilities. The limited research on siblings of adults with intellectual disabilities in Chinese societies is consistent with the trend of mainstream Chinese family studies which has largely overlooked research on siblings (Wang et al., Citation2022), regarding such relationships as less important than those between different generations (Fei, Citation1939). Future research in Chinese societies about siblings with and without intellectual disabilities might benefit from considering the perspectives of a more diverse range of participants, including parents, siblings with disabilities, and service providers and exploring aspects of relationships beyond caregiving. More research on this topic is needed to understand the adult sibling relationships where one has intellectual disability in mainland China and Hong Kong. In mainland China, future research might prioritise remote and rural areas where 75.04% of people with disabilities reside (Yang, Citation2012).

Importantly, the increased longevity and ageing of adults with intellectual disabilities and their parents, will lay new foundations for research on sibling relationships, as siblings replace their parents and are likely to become recipients of state support to maintain family caregiving. Current disability policies in mainland China, Hong Kong, Macao, and Taiwan place a strong emphasis on supporting family members of people with disabilities (Macao SAR Government, Citation2016; RAC, Citation2020; State Council, Citation2021; Taiwan Ministry of Health and Welfare, Citation2021). However, these policies do not differentiate siblings without disabilities as a specific category from other family members. As changes in caregiving responsibility occur it will be important to understand the needs of siblings without disabilities, their sources of satisfaction and the challenges they face in meeting responsibilities. Such knowledge will assist in thinking about how they can best be supported with caregiving and to collaborate and work in partnership with the disability organisations whose mandate is to complement their caregiving. Disability policies and service programs may need to be refined to more clearly address siblings’ particular needs, especially in middle and late adulthood.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Arksey, H., & O’Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology: Theory and Practice, 8(1), 19–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616

- Avieli, H. (2020). How middle-aged siblings of adults with intellectual disability experience their roles: A qualitative analysis. Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities, 32(4), 633–651. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10882-019-09710-3

- Avieli, H., Band-Winterstein, T., & Araten Bergman, T. (2019). Sibling relationships over the life course: Growing up with a disability. Qualitative Health Research, 29(12), 1739–1750. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732319837228

- Bigby, C. (1997). Parental substitutes: The role of siblings in the lives of older people with intellectual disability. Journal of Gerontological Social Work, 29(1), 3–21. https://doi.org/10.1300/J083v29n01_02

- Burbidge, J., & Minnes, P. (2014). Relationship quality in adult siblings with and without developmental disabilities. Family Relations, 63(1), 148–162. https://doi.org/10.1111/fare.12047

- Chen, L. (2011). Phenomena of care experiences of two-generation-elderly families with adults with intellectual disabilities (in Chinese). Journal of Senior Citizens Service and Management, 1(1), 138–165. https://doi.org/10.29745/JSCSM.201104.0005

- Chen, R., & Yu, M. (2023). Emerging resilience: Stress and coping strategies in Chinese families living with children with disabilities. Disability and Society. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2023.2215391

- Chen, W. W., Wu, C. W., & Yeh, K. H. (2016). How parenting and filial piety influence happiness, parent–child relationships and quality of family life in Taiwanese adult children. Journal of Family Studies, 22(1), 80–96. https://doi.org/10.1080/13229400.2015.1027154

- Cheung, C. K. (2015). Parent-child and sibling relationships in contemporary Asia. In S. R. Quah (Ed.), Routledge handbook of families in Asia (pp. 230–245). https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315881706

- Chien, W. T., & Lee, I. Y. M. (2013). An exploratory study of parents’ perceived educational needs for parenting a child with learning disabilities. Asian Nursing Research, 7(1), 16–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anr.2013.01.003

- Chiu, C. Y. (2021). Bamboo sibs: Experiences of Taiwanese non-disabled siblings of adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities across caregiver lifestages. Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities, 162. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10882-021-09797-7

- Chiu, M. Y. L., Yang, X., Wong, F. H. T., Li, J. H., & Li, J. (2013). Caregiving of children with intellectual disabilities in China - an examination of affiliate stigma and the cultural thesis. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 57(12), 1117–1129. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2788.2012.01624.x

- Chou, Y.-C., & Kröger, T. (2020). Ageing in place together: Older parents and ageing offspring with intellectual disability. Ageing & Society, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X20001038

- Chou, Y. C., Kröger, T., & Pu, C. Y. (2018a). Underemployment among mothers of children with intellectual disabilities. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 31(1), 152–158. https://doi.org/10.1111/jar.12336

- Chou, Y. C., Li, W. P., & Wang, W. C. (2018b). Care transition and moving in old age among older two-generation families: Older parents, ageing offspring with intellectual disability and their siblings (in Chinese). NTU Social Work Review, 37, 99–149. https://doi.org/10.6171/ntuswr2018.37.03

- Davys, D., Mitchell, D., & Haigh, C. (2011). Adult sibling experience, roles, relationships and future concerns - a review of the literature in learning disabilities. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 20(19–20), 2837–2853. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2702.2010.03530.x

- Davys, D., Mitchell, D., & Haigh, C. (2015). Futures planning - adult sibling perspectives. British Journal of Learning Disabilities, 43(3), 219–226. https://doi.org/10.1111/bld.12099

- Deng, M., Poon-Mcbrayer, K. F., & Farnsworth, E. B. (2001). The development of special education in China: A sociocultural review. Remedial and Special Education, 22(5), 288–298. https://doi.org/10.1177/074193250102200504

- Dew, A. H. (2010). Recognising reciprocity over the life course: Adults with cerebral palsy and their non-disabled siblings [Doctoral Dissertation, The University of Sydney]. The University of Sydney. http://hdl.handle.net/2123/7111.

- Fan, G. Y., & Chen, C. F. (2022). “Why is it only me?”: Obedience and confrontation when adult siblings inherit the family caregiver role (in Chinese). NTU Social Work Review, 45, 45–88. https://doi.org/10.6171/ntuswr.202206

- Fan, R. (2007). Which care? Whose responsibility? And why family? A confucian account of long-term care for the elderly. Journal of Medicine and Philosophy, 32(5), 495–517. https://doi.org/10.1080/03605310701626331

- Fei, H. (1939). Peasant life in China: A field study of country life in the Yangtze valley. Paul, Trench, Trubner.

- Fei, X. (1992). From the soil: The foundation of Chinese society. University of California Press.

- Fu, W., Deng, M., & Cheng, L. (2020). An ethic of care for people with disabilities during the COVID-19 pandemic in China: Towards greater social justice. Knowledge Cultures, 8(3), 60–67. https://doi.org/10.22381/KC8320209

- Garzón, A. (2000). Cultural change and familism. Psicothema, 12(SUPPL. 1), 45–54.

- Griffiths, D. L., & Unger, D. G. (1994). Views about planning for the future among parents and siblings of adults with mental retardation. Family Relations, 43(2), 221–227. https://doi.org/10.2307/585326

- Heller, T., & Arnold, C. K. (2010). Siblings of adults with developmental disabilities: Psychosocial outcomes, relationships, and future planning. Journal of Policy and Practice in Intellectual Disabilities, 7(1), 16–25. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-1130.2010.00243.x

- Holroyd, E. (2003). Hong Kong Chinese family caregiving: Cultural categories of bodily order and the location of self. Qualitative Health Research, 13(2), 158–170. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732302239596

- Hu, X., Wang, M., & Fei, X. (2012). Family quality of life of Chinese families of children with intellectual disabilities. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 56(1), 30–44. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2788.2011.01391.x

- Huang, V., & Fiocco, A. J. (2020). Measuring perceived receipt of filial piety among Chinese middle-aged and older adults. Journal of Cross-Cultural Gerontology, 35(2), 195–208. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10823-019-09391-7

- Kim, D. S., He, Y., & Lee, Y. (2020). The relationship between the ethnic composition of neighbourhood and fertility behaviours among immigrant wives in Taiwan. Asian Population Studies, 16(2), 201–219. https://doi.org/10.1080/17441730.2020.1757849

- Kuo, Y. C. (2014). Brothers’ experiences caring for a sibling with Down syndrome. Qualitative Health Research, 24(8), 1102–1113. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732314543110

- Kuo, Y. C. (2015). Women’s experiences caring for their husbands’ siblings with developmental disabilities. Global Qualitative Nursing Research, 2, 134. https://doi.org/10.1177/2333393615604169

- Kuo, Y. C., & Geraci, L. M. (2012). Sister’s caregiving experience to a sibling with cerebral palsy- the impact to daughter-mother relationships. Sex Roles, 66(7–8), 544–557. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-011-0098-y

- Lee, C., & Burke, M. M. (2020). Future planning among families of individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities : A systematic review. Journal of Policy and Practice in Intellectual Disabilities, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1111/jppi.12324

- Lee, C. E., & Burke, M. M. (2018). Caregiving roles of siblings of adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities: A systematic review. Journal of Policy and Practice in Intellectual Disabilities, 15(3), 237–246. https://doi.org/10.1111/jppi.12246

- Lee, C. E., Hagiwara, M., Chiu, C. Y., & Takishima, M. (2022). Caregiving and future planning perspectives of siblings of individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities: Insights from South Korea, Japan and Taiwan. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/jar.13033

- Li, E. P. Y. (2006). Sibling advocates of people with intellectual disabilities. International Journal of Rehabilitation Research, 29(2), 175–178. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.mrr.0000191845.65198.d7

- Liang, L. (2021). The predictors of sibling relationship of adults with intellectual disability: Analysis based on mediation effect of contact motivation (in Chinese). Social Work and Management, 21(2), 49–58.

- Liang, L. (2023). Affiliated stigma and contact frequency in sibling relationships of adults with intellectual disabilities: The mediation of relational motivations. International Journal of Developmental Disabilities, 69(5), 728–737. https://doi.org/10.1080/20473869.2021.2014740

- Liang, L. Y. (2015). Sibling relationship of adults with intellectual disabilities in China [Doctoral Dissertation, The University of Hong Kong]. The University of Hong Kong. http://hdl.handle.net/10722/211109. https://doi.org/10.5353/th_b5481888.

- Liu, W. (2011). Change and continuity of family values (Jiating jiazhi de bianqian yu yanxu) (In Chinese). Social Science, (10), 78–89. CNKI:SUN:SHKX.0.2011-10-011

- Liu, Y. J., Chiu, C. Y., Chang, H. H., & Ko, C. S. (2020). Double special: A qualitative exploration of work- family border-crossing experiences of nondisabled siblings with a career in special education (in Chinese). Bulletin of Special Education, 45(3), 29–51. https://doi.org/10.6172/BSE.202011

- Lo, W. Y. W. (2016). The concept of greater China in higher education: Adoptions, dynamics and implications. Comparative Education, 52(1), 26–43. https://doi.org/10.1080/03050068.2015.1125613

- Lu, S. H., Chiang, I. T., & Wang, C. H. (2008). A living home: Development of interdependent home model for adult people with intellectual disabilities (in Chinese). Journal of Special Education, 28. https://doi.org/10.6768/JSE.200812.0001

- Luo, M. S., & Chui, E. W. T. (2018). Gender division of household labor in China: Cohort analysis in life course patterns. Journal of Family Issues, 39(12), 3153–3176. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X18776457

- Macao SAR Government. (2016). Ten year plan for rehabilitation services from 2016 to 2025. http://www.ias.gov.mo/wp-content/themes/ias/tw/download/rehabilitation-service10n-ghwb_cwz.pdf

- Meltzer, A. (2018). Embodying and enacting disability as siblings: Experiencing disability in relationships between young adult siblings with and without disabilities. Disability and Society, 33(8), 1212–1233. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2018.1481016

- Múries-Cantán, O., Schippers, A., Giné, C., & Blom-Yoo, H. (2022). Siblings of people with intellectual and developmental disabilities: A systematic review on their quality of life perceptions in the context of a family. International Journal of Developmental Disabilities, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/20473869.2022.2036919

- Orsmond, G., & Seltzer, M. (2000). Brothers and sisters with mental retardation: Gendered nature of the sibling relationship. American Journal of Mental Retardation, 105(6), 486–508.

- Pan, L., & Ye, J. (2015). Family care of people with intellectual disability in rural China: A magnified responsibility. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 28(4), 352–366. https://doi.org/10.1111/jar.12167

- Qian, L. (2022). Ethnographic imagination as an interpretative approach to the world of infants and children with developmental disabilities. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 21. https://doi.org/10.1177/16094069221129032

- Qu, Y. (2020). Understanding the body and disability in Chinese contexts. Disability and Society, 35(5), 738–759. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2019.1649123

- Rehabilitation Advisory Committee. (2016). Report of working group on ageing of people with intellectual disability.

- Rehabilitation Advisory Committee. (2020). Persons with disabilities and rehabilitation programme plan.

- State Council. (2021). Plan for protection and development of disabled people during the 14th Five-Year Plan (2021-25) period. http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/content/2021-07/21/content_5626391.htm

- Taiwan Ministry of Health and Welfare. (2021). People with disabilities rights protection act. https://law.moj.gov.tw/ENG/LawClass/LawAll.aspx?pcode=D0050046

- Wang, Y. Z., Li, Y., Liu, T., Zhao, J., Li, Y., & Niu, X. (2022). Understanding relationships within cultural contexts: Developing an early childhood sibling relationship questionnaire in China. Family Relations, 71(1), 220–237. https://doi.org/10.1111/fare.12586

- Xun, K., & Cui, J. (2022). Family-oriented practice in disability services in Hong Kong: A cross-sectoral social work perspectives in the fields of intellectual disability and mental illness. Health & Social Care in the Community, 30, e5714–e5724. https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.14001

- Yan, J., & Chang, M. (2021). A self-narrative inquiry about a normal sibling who has a brother with profound disabilities (in Chinese). Journal of Understanding Individual with Disabilities, 17(2), 26–48. https://doi.org/10.6513/JUID.202101

- Yan, Y. (2018). Neo-familism and the state in contemporary China. Urban Anthropology, 47(3,4), 181–224.

- Yang, J. (2012). Compensating for disability identity through marriage: A grounded theory study on married women with disabilities in a Southwest Chinese township [Doctorial Dissertation, The Hong Kong Polytechnic University]. The Hong Kong Polytechnic University. https://theses.lib.polyu.edu.hk/handle/200/7225.

- Yang, X. (2015). No matter how I think, it already hurts: Self-stigmatized feelings and face concern of Chinese caregivers of people with intellectual disabilities. Journal of Intellectual Disabilities, 19(4), 367–380. https://doi.org/10.1177/1744629515577909

- Yang, X., Byrne, V., & Chiu, M. Y. L. (2016). Caregiving experience for children with intellectual disabilities among parents in a developing area in China. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 29(1), 46–57. https://doi.org/10.1111/jar.12157