ABSTRACT

Background:

This study investigated the extent to which behaviour support services are accessible under Australia’s National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS).

Method:

We conducted semi-structured interviews with families who support a member with an intellectual disability and challenging behaviour. We analysed this data with a supply and demand access framework initially designed for health care and described the lived experiences of participants and their families accessing behaviour supports. Results show that while the NDIS has improved participants’ ability to pay for behaviour (and other) supports, this financial capacity represents only one of six other important aspects of access.

Results:

Families compensate for the shortcomings of the marketised environment which has arisen under the NDIS.

Conclusion:

This raises questions about the responsibilities of support provision, which is obscured in the new NDIS system and places responsibility for successfully accessing behaviour supports onto the family of the person with an intellectual disability.

Since 2013 Australia has undergone major changes in disability policy and funding, transitioning from a welfare model to a social insurance model, in line with the National Disability Strategy (Council of Australian Governments Citation2010). These changes, instituted through the National Disability Insurance Scheme’s (NDIS) rollout, which began in 2016, radically changed the way funding is allocated both to people living with disabilities and to the organisations who support them, by providing eligible NDIS participants with direct, individualised funding. The new “insurance model” was designed to promote freedom of choice and control for individuals to choose their paid support, while simultaneously promoting the growth of a privatised market of disability support providers (Productivity Commission, Citation2011). Funding is determined by the NDIS, based on a principle of what is considered to be “reasonable and necessary” (Foster et al., Citation2016).

One group of people supported by the NDIS are those with intellectual disabilities who sometimes use challenging behaviours, which are defined as behaviours that pose a significant risk of harm, or that result in limitations to ordinary access to community facilities (Emerson & Einfeld, Citation2011; Hastings, Citation2002). Challenging behaviours have been attributed to interpersonal, biological and environmental stressors (van den Bogaard et al., Citation2019) or psycho-social vulnerabilities, such as not being able to communicate, not having needs met, or experiencing pain, and may function to fulfil those needs, particularly for individuals with communication disorders and complex communication needs (Hastings, Citation2002). These behaviours may include destruction of property or aggression towards self or others (Emerson & Einfeld, Citation2011), and are typically associated with family stress and anxiety (Beqiraj et al., Citation2022) and are typically ongoing (Totsika et al., Citation2008). Families supporting people who use challenging behaviour often face a range of challenges such as interpersonal violence, destruction of their home environment, sleep deprivation, high levels of depression and stress, and social isolation (Dreyfus & Dowse, Citation2020; Duignan & Connell, Citation2015; Hubert, Citation2011; Maes et al., Citation2003; Ng & Rhodes, Citation2018).

In 2016 we interviewed 26 such families from across the Australian states of New South Wales, Queensland, South Australia and Western Australia. The purpose of these interviews was to understand families’ experiences of the behaviour support services they receive, because, at the time, there was no research into behaviour support service access in Australia, and behaviour support was to be one of the services offered under the NDIS (Dreyfus & Dowse, Citation2020). The primary goal of positive behaviour support is increasing a person with a disability’s quality of life, with a corresponding goal of decreasing the severity and frequency of their behaviours of concern (Sailor et al., Citation2009). Effective behaviour support requires a supportive social environment and works to strengthen relationships between informal and formal supports and the person with disability (Emerson & Einfeld, Citation2011; Dowse et al., Citation2017). The 2016 study showed that parents provided a high level of support to their family member across a range of areas that included making and attending appointments, recruiting and training support staff, monitoring the appropriateness and quality of services, modifying their house and life to suit their family member’s needs, changing career and undergoing education to best support their family member, advocating for adequate support, and providing intensive support in many functional activities of daily living (Dreyfus & Dowse, Citation2020). Additionally, the challenges faced by families included barriers to accessing supports, a lack of knowledge about available services, an inability to navigate the complex disability support system, deficits in resourcing in regional areas, extensive waiting lists, long planning processes, over prescription of medication in lieu of adequate support and a lack of behaviour support practitioners (Dowse et al., Citation2017; Dreyfus & Dowse, Citation2020).

Since then, the NDIS’s shift in disability policy towards funding individuals rather than organisations has reframed the government’s responsibility to providing access to support, rather than providing the support itself. Based on a person-centred model of support, this environment emphasises the need for people with disabilities (or their proxies) to be able to articulate their support needs and to frame those needs in terms of their development towards social and economic participation (Productivity Commission, Citation2011).

There have been number of studies conducted into access and participation in the NDIS since its inception in 2016. Some of these studies examine the scheme from the perspective of participants with disabilities (e.g., Smethurst et al., Citation2021; Loadsman & Donelly, Citation2021) and some from the perspective of practitioners and service providers (such as speech pathologists, occupational therapists and support co-ordinators) (e.g., Foley et al., Citation2021; Jessup & Bridgman, Citation2022). From the participant side, studies have shown that access to the NDIS and services funded through the NDIS is not equitable; females, Indigenous people, people who are hard to reach because of socio-economic and/or other disadvantages, people with complex problems such as disability and mental health issues and people who live outside of metropolitan areas have more difficulty accessing services and participating in the scheme (Cortese et al., Citation2021; Johnsson & Bulkeley, Citation2021; Prowse et al., Citation2022; Trounson et al., Citation2022; Yates et al., Citation2021).

While some people are successful in accessing the scheme, studies report that people also can find it complex, overwhelming and difficult to navigate (Prowse et al., Citation2022; Barr et al., Citation2021; Smethurst et al., Citation2021; Gavidia-Payne, Citation2020). Many participants and their families also report delays in accessing services (Jessup & Bridgman, Citation2022; Barr et al., Citation2021; Smethurst et al., Citation2021) especially away from metropolitan areas.

While the NDIS has been reported as not providing enough support for participants to access it (Prowse et al., Citation2022; Trounson et al., Citation2022; Cortese et al., Citation2021), other studies have shown that the participation rate of some people increases when programs that are tailored to specifically meet people’s needs and when programs inform them, involve them and build trusting relationships with them. For example, White et al.’s (Citation2021) study of a program in the Kimberly region of Western Australia, which aimed to support Aboriginal people to access the NDIS, found that access increased due to the program being controlled and implemented by members of the Aboriginal community who had the trust of community members, were able to provide culturally appropriate services and utilised a strengths-based approach in their work with Aboriginal people with disabilities and their families. The result was some of the barriers that have prevented Aboriginal engagement with disability services in the past were overcome.

Given the purported accessibility of behaviour support in the NDIS context, the aim of this study was to investigate the extent to which the families who were interviewed about behaviour support in 2016 have been able to successfully access behaviour support once they came under the NDIS. Foley et al. (Citation2021, p. 3022) make the important point that participation (in the NDIS) is a complex thing to assess and in fact involves a “dynamic relationship between a person and their environment,” an idea which we develop in this paper by applying a model of access that focuses on both the person and the service provision environment as having features that need to be recognised and achieved if access is going to be regarded as successful.

A conceptual framework of access

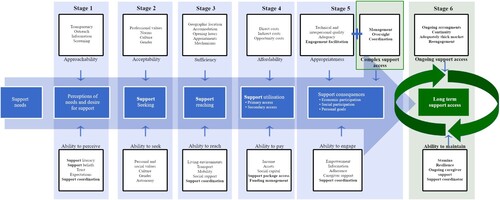

The conceptual framework used to analyse the interview data in the present study is based on Levesque et al.’s (Citation2013) Access Model (see ), which construes access as a linear progression through five stages, with facilitators or barriers to access paired across two horizontal axes. The top axis is the “supply side,” which refers to the attributes of healthcare services (approachability, acceptability, availability and accommodation, affordability, and appropriateness). The bottom axis refers to five “demand side” attributes of “patients” (the ability to perceive, seek, reach, pay and engage with care). Further, “access” is framed as the outcome of successfully navigating all stages of the access journey. Framing the axes as “supply” and “demand” highlights that the process, barriers and facilitators of access to health care exist as part of an economic exchange in the healthcare services marketplace. The access model’s delineation of the two axes of “supply” and “demand” also aligns with the NDIS marketplace, which involves interactions between both service providers and “consumers.” Further, the shift to an emphasis on “choice and control” in the Australian disability environment requires individuals to articulate their needs as consumers within a free market of disability services while also expecting service providers to respond to the forces of consumer demand (Productivity Commission, Citation2011).

Within the disability context then, the “supply” side of the access model relates to service provision, and the “demand” side to NDIS participants. The NDIS can thus be seen as a means of access, and its efficacy is the extent to which it supports both participants and providers across the different dimensions of access. As NDIS participants are framed as consumers who differ in the knowledge and skills required to achieve access, the framework can also identify barriers to access from the “demand” side. It is therefore a useful heuristic for examining access to behaviour support, as we do in this paper.

At each stage of the model, the “supply” side and “demand” side features are related concepts. For example, the ability to pay (demand side) is inherently linked to the affordability of services (supply side). Further, barriers to access can occur in any of the five features as a result of issues on either the supply side or the demand side. This dimensional operationalisation of access can explain differences in participant access outcomes and specify policy areas to address. Where supply side issues exist, service structures can be improved. Where demand side barriers exist, policies and interventions can assist people to build the skills that enable access. This model of access has been utilised as a framework for systematic and literature reviews across health care, aged care (Phillipson & Hammond, Citation2017), in culturally and linguistically diverse populations, mental health (Wall et al., Citation2021), and disability research (Matin et al., Citation2021). As yet, however, it has not been used as a methodological framework for the analysis of data nor in the disability context.

The present research utilised this framework to explore our research question: to what extent have families been able to successfully access behaviour support under the NDIS?

Method

This study used a combined inductive-deductive approach that begins with an established framework for deductively coding the data and incorporates new data-driven code categories that reflect participants experiences. In the present study, Levesque et al.’s (Citation2013) framework of access to health care was adapted to the disability context. Data were gathered through semi-structured interviews with parents of people with ID who use challenging behaviour (see Appendix, part 2). Interviewees were asked about their experiences of accessing behaviour support since the introduction of the NDIS, compared with their experiences before the NDIS.

Participants

Participants for the study comprised a number of those who were recruited to the initial 2016 study. Potential participants in the initial study were approached via callouts in disability organisation newsletters, popular Australian Facebook disability groups, and through a snowball networking method. All 26 families who participated in the 2016 study were approached directly with an offer to participate in a follow-up interview.Footnote1 They all had a family member with intellectual disability who had been in receipt of behaviour support services, and of these, 14 agreed to participate and were interviewed in 2020. As shows, the 14 interviewees came from 3 states: New South Wales, Queensland, and Western Australia, and all were mothers of people with ID, the majority of whom were male (64%) and ranged in age from 8 to 55 years old (M = 24.79; see ). Five lived at home, seven lived in different kinds of supported independent living (SIL) arrangements providing 24-hour support, and two lived independently with in-home supports. All lived in urban areas. Interviewees received a $50 gift card for participation. Ethics approval was granted by the University of Wollongong Human Research Ethics Committee.

Table 1. Interviewees and their family member NDIS participants.

Data collection

The semi-structured interviews, which lasted around one hour, were conducted online by the first researcher. These began by summarising the interviewee’s 2016 interview in order to remind them about what had been happening then and to encourage them to draw comparisons with the present. Open-ended interview questions (see Appendix) focused on interviewees’ experiences accessing behaviour support services and the responsiveness of services. Interviewees were prompted to speak about whether the services they were currently using were meeting the needs of their family member with disability, and the family as a whole, as well as the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic and lockdowns on support access. Interviews were recorded with consent and transcribed verbatim. All interviews were entered into the qualitative data analysis software NVivo.

Data analysis

Analysis of the interviews was informed by a codebook methodology (Roberts et al., Citation2019; Crabtree & Miller, Citation1992), which was developed from the a priori framework of Levesque et al.’s (Citation2013) access to healthcare model. This was used for deductive coding, while allowing for the development of inductive data-driven codes, enabling a richer analytic framework that reflected the experiences of interviewees (Roberts et al., Citation2019). The second researcher applied and developed the codebook, which contained Levesque et al.’s (Citation2013) five code categories, named for the five stages of access in the model, with definitions and prototypical examples adapted to the disability context. The codebook was revised after discussions between the two researchers about the initial coding round. Two new data-driven themes were developed and added to the “supply” side, as per , expanding service appropriateness to include the factor of complex support access, as well as adding a sixth stage to conceptualise and cover the important factor of ongoing support access. Transcripts were then re-coded by the second researcher, while also looking for counterinstances in order to maintain credibility (Beck, Citation1993; Crabtree & Miller, Citation1992). An updated access framework was created to reflect the new thematic structure ().

Credibility was enhanced by direct quotations, and fittingness can be assessed by the inclusion of interviewee characteristics. Auditability was demonstrated through descriptions of interviewee characteristics, codebook categories and their theoretical antecedent (Levesque et al., Citation2013), and the analytic process (Beck, Citation1993). To reduce bias, the data, assigned codes and emerging themes were discussed by the researchers throughout the process of analysis and any disagreements about coding were resolved through discussion.

Results and discussion

While the Levesque et al. framework was useful to understand some barriers and facilitators of access in the present research, it did not account for all challenges the interviewees reported, thus new data-driven categories were added (in green), creating an expanded model of access for the disability support context, for accessing self-managed, individualised, personalised/direct payments or funds for behaviour support, as displayed in . Each feature is explained in detail in the results section.

The results of applying this model are categorised according to the revised framework depicted in , with each of the combined supply and demand stages explained in turn. In some cases, the supply and demand side are discussed separately, but in others, where they are seen to be inextricable, these are discussed together. The results section is thus structured into six sections, one for each combined supply and demand stage of the revised framework. The first four stages are in line with the original framework, with stage 5 adapted to include complex care access factors, and the new stage 6, conceptualising the factors of ongoing care access. Given the detailed nature of this model, we have put the discussion of individual points within each results section, with a global discussion of the findings collectively following the results.

Stage 1: Perceptions of needs and desires for supports

1a. Demand side – The ability to perceive

The ability to perceive relates to health literacy, trust and expectations in healthcare provision and awareness of health needs, which can equally apply in the disability support context. Indeed, in the current disability funding model, a person (or their representative) needs to be able to perceive what the needs are in order to be able to request the funding for services to meet that need. In the present research, all interviewees had high health and disability literacy as well as substantial lived experience supporting a person with disability. Their ability to perceive need and understand the benefits of behaviour support for their family member was evident in their talk of diagnostic labels and therapeutic practices. However, in some instances, their perception of need and available supports had been developed with guidance from disability support practitioners. These instances of effective behaviour support involved education and building the family’s perception of needs:

Yeah, so that’s been a real positive too. I would never have thought to get a speech therapist involved, and [the behaviour support practitioner] has opened up that world for us as well. (Interviewee 8)

1b. Supply side – Approachability

The approachability of a service refers to the extent to which service providers advertise and communicate the service’s purpose and how to access it, as well as transparency around the nature and efficacy of the support on offer. In the disability context, greater service provider approachability would act as a facilitator to access, by informing NDIS participants and their families of the supports that exist and the expected outcomes of those supports.

Interviewees did not directly reference the approachability of specific service providers, however many participants referenced a need to deeply understand the disability support industry more generally before seeking support through the National Disability Insurance Agency (NDIA) assessment process, which involves assessment by an NDIA planner who determines the potential NDIS participant’s support needs. While this process could potentially support approachability by informing participants of available services, many stressed that they only got what they need because they understood the system and how to argue for what their family member needed.

If you know what to ask for, if you know how to argue the case, you can get a good amount of funding and address all the person’s needs. (Interviewee 1)

Approachability is of particular importance for people with intellectual disability but can also apply to others with disabilities and their informal supporters, where complex therapeutic supports and a lack of knowledge about what they are and how they work can be a barrier; that is to say, people don’t know what they don’t know. In particular, for people who use challenging behaviour, behaviour support practices are complex and may involve multiple treatment modalities and staff. For these interviewees, a very high level of knowledge about therapeutic efficacy, practitioner quality and system navigation was necessary to enable successful access to support for their family member, showing the interaction between approachability and the ability to perceive.

Stage 2: Support seeking

2a. Demand side – “Ability to seek” and 2b. Supply side – “Acceptability”

The ability to seek (demand side) and acceptability (supply side) are discussed together here, as they refer to two inseparable perspectives on the cultural acceptability of the service, which needs some explanation before reporting on our findings. Under the Levesque et al. (Citation2013) framework, social and cultural norms and values, and the professional values present in a care service constitute the “acceptability” of the care service provision. An individual may perceive a need for care but be unable to seek it if the care provision is not acceptable to them. Thus, when applied to disability support, support seeking may be facilitated by providers whose values and cultural practices align with people with ID and their families or barred where they do not.

In this context, a relevant cultural value is the reorientation of people with disabilities as “subjects” requiring support rather than “objects” receiving it, in line with the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (Citation2006). This is mainly operationalised through the NDIA’s emphasis on individual choice and control; thus the person-centred model of the NDIS was seen as a positive change by most interviewees:

Being able to have a self-managed package around therapy and choose who works with [my son] and having the flexibilities around (sic)[him], that’s been amazing. (Interviewee 10)

Stage 3: Support reaching

3a. Demand side – “Ability to reach” and 3b. Supply side – “Availability & accommodation”

The “ability to reach” (demand side) includes factors that enable access such as personal mobility and transport, while “availability and accommodation” (supply side) refers to spatial availability, that is, where services are located, including distribution across rural and regional areas, and sufficient resourcing to produce enough qualified support to meet the demand for services (e.g., Gao et al., Citation2019; Lakhani et al., Citation2019). While in the original model, accommodation refers to the ability of services to accommodate patient demand, as NDIS participants may be provided residential accommodation, we have changed this label to “sufficiency” to avoid confusion.

3a. Demand side – The “ability to reach”

To reach services, all interviewees’ family members required complete support because they typically could not be in the community alone and needed to be accompanied and driven to all places. For most, this was facilitated by the NDIS and the funding it provided. This means that this part of the model was successfully achieved by most interviewees as they had NDIS packages and funding for supports which were often provided in-home, or else transport arrangements were funded within their NDIS packages. However, in one counter instance, access to transport was disrupted by the transition to the NDIS model of funding.

So, the house used to have a car, right? A community car, and they’d run them everywhere in it, and when the NDIS came in, that went. (Interviewee 3)

3b. Supply side – Availability and sufficiency

Availability and sufficiency of services is very relevant to behaviour support services under the NDIS, with problems already noted by prior research about a lack of availability of behaviour support services, especially in rural and remote areas (Gao et al., Citation2019; Lakhani et al., Citation2019). Indeed, availability and sufficiency of services in rural and remote areas is a major focus of NDIA internal research and evaluation of market-based service provision (NDIA, Citation2021) and previous studies have reported that families move away from rural and remote areas, where services are limited or non-existent, to metropolitan areas, so they can gain access to services (see e.g., Dreyfus & Dowse, Citation2020; Lakhani et al., Citation2019). One family in our study had previously moved interstate in order to be closer to services, however, no interviewees reported current access challenges due to regionality, as all lived in urban areas.

Much more significant, regardless of location, was the insufficient number of behaviour support practitioners, with most interviewees reporting that they had to wait for services for a minimum of weeks and even up to more than a year:

There are still wait lists if you’re looking for behaviour support. I see it on all the online forums, … I know they only have a handful of practitioners. It still seems to be like this really, you’re skimmingFootnote2 (sic) to find people because they’re just not available. (Interviewee 9)

Even when families had managed to secure a service contract with a behaviour support practitioner, in many instances interviewees still weren’t receiving adequate services due to providers’ high caseloads or waiting lists:

[The behaviour support practitioner] ended up not having the time to do the stuff that we really need for [our daughter], the intense behaviour support plan. He felt he needed somebody that can spend a lot more hours being with [our daughter] enough (sic), and drawing up a big plan. His workload is really huge. (Interviewee 14)

… they didn’t replace [the behaviour support practitioner] after three weeks after she left and so I just emailed and said, “Look, you haven’t found a replacement. We’re sitting here not talking to anybody. We don’t have a plan. We’re now over six months into the NDIS plan. We need to have the service.” (Interviewee 9)

This lack of available behaviour support practitioners, their heavy caseloads and the lack of adequate time was emphasised by interviewees as the most significant barrier to accessing behaviour support.

Availability may also be facilitated by the flexibility of services, which during the COVID-19 pandemic, often included providing online options (Johnsson & Bulkeley, Citation2021). However, while virtual support was made available to some during the COVID-19 restrictions, many interviewees reported that their family member required in-person support not virtual support to meet their needs. For one family who could make use of online therapeutic appointments, this presented a new challenge, as they needed to both organise and facilitate these sessions in their home:

With COVID, … All [my son’s] sessions are tele-health. Which still needs a certain amount of structure around it. (Interviewee 13)

Support coordination as an additional factor in facilitating access under “availability”

Under the NDIS, participants can be funded for a support coordinator to help them navigate the system and access supports. Under our remodelled access framework, support coordinators (SCs) can be understood as a facilitator of access, because of their responsibilities to help NDIS participants and their families understand their NDIS plan (the “ability to perceive”), and to help plan, engage with and coordinate supports (the “ability to reach”). While interviewees recognised the benefits of engaging an SC, the challenge of accessing and, in particular, maintaining funding for an SC can be a barrier for people beginning their NDIS journey, with the NDIA frequently trying to move people out of this service. As one interviewee articulated:

My daughter’s got her own support coordinator, which they tried to do away with in the beginning. (Interviewee 3)

As support coordinators are private providers, the appropriateness and quality of an individual SC’s service can vary. Further, even securing support coordination could be seen to act as an additional barrier to accessing therapeutic supports because it is an additional step that participants go through before they can access those supports.

Stage 4: Support utilisation

4a. Demand side – “Ability to pay” and 4b. Supply side – “Affordability”

4a. Demand side – The “ability to pay”

While the ability to pay has been a key access issue in the disability sector (NDIA, Citation2021; National People with Disabilities & Carer Council Citation2009), the Levesque et al. (Citation2013) framework situates the financial aspect as only one of the five stages of access. Funding for services is central to the NDIS, with individualised funding packages for NDIS participants enabling their “ability to pay” for the services needed. Overall, at the time of the interviews for the present study, all but one family had an NDIS plan with individual funding for behaviour support services, and many reflected that this allocation of funding had made a substantial and positive impact on their family member’s access to adequate supports, including behaviour support. However, others had not yet been able to access adequate behaviour support, sometimes despite having the funding for it, reflecting the importance of understanding the different dimensions of access.

Nonetheless, the dominant perspective of interviewees was that this element of access was now successfully facilitated under the NDIS, due to the fact that there was now funding they previously didn’t have:

With all the different carers that she has and in her living arrangements now, which are different from before, there’s lots of support for her … it’s going very well since we’ve had funding. (Interviewee 7)

Given the integrated nature of behaviour support with other aspects of people’s lives, the ability to pay also relates to meeting the needs of other activities of daily living, such eating, dressing, personal hygiene and so on. These vary in intensity, as some participants require support from disability support workers for activities of daily living at all times. In addition to costs related to accommodation, transportation and daily activities, behaviour support often requires many hours from a professional and constitutes a significant extra expense. At the time of writing, one hour of a behaviour support practitioner ranged in cost from $214.41 to $352.25, depending on which state the service provision occurred in and whether it was rural or remote (NDIA Citation2021). For some interviewees, their current NDIS funding package enabled these diverse and extensive supports, which had not previously been affordable.

… the NDIS has given us funding to be able to employ the right support work team for him and to have the right amount of energy* around him to meet his needs. (Interviewee 10)

(*energy refers to having enough disability support workers around to support the participant’s son, who requires intensive support at all times.)

Supports were cut by 70% because they seemed to think [my son] was so independent that he didn’t need the support. When in fact all of his endeavours, work and play and everything, were only possible because of the support. (Interviewee 11)

While this decision may match the NDIA’s goal to fund “reasonable and necessary supports” (NDIS Act, 2013, Section 34), the occurrence of challenging behaviour is unpredictable and can fluctuate or intensify over the life course in response to stressful or traumatic life events (Dowse et al., Citation2017). Challenging behaviour is well understood as a response to not having one’s needs met (Hastings, Citation2002), which may occur when funding is reduced for the very supports that meet those needs, as indicated by the quote directly above. This is particularly concerning when combined with the extensive wait times to access this kind of support because when challenging behaviour recurs, families have to re-seek this support anew, and again wait for provider availability, when what is required is a quick response. This fluctuating funding model poses the risk of losing access to behaviour support and thus poses a potential risk of harm to both the person who uses challenging behaviour as well as their family.

4b. Supply side – Affordability

The affordability of a service refers to the direct expenses of accessing services (Levesque et al., Citation2013). Under the NDIS, funding packages are matched to the actual costs of needed supports, so the affordability of services should be ensured by the NDIS. However, in some instances, interviewees reported that their allocation for behaviour support was not adequate for effective implementation. Given this issue is integrated with the timeliness of services, it is discussed below in service appropriateness (subsection “timeliness”).

Additional factors related to affordability in the original framework include the opportunity cost of time spent in treatment for the person seeking health care, which may pose a barrier, and the accessibility of payment method, where providing multiple payment options (such as Eftpos, and payment plans) facilitates access (Levesque et al., Citation2013). In the NDIS context, this concept needs to be broadened to include the administration of the funding package that participants receive. The NDIS allows participants to choose their level of assistance in the administration of payments and management of their plan. In the present study, half the interviewees’ family members’ support package was self-managed by the parents, who administered all payments because it gave them greater control over their funding and more flexibility in choosing providers. However, while self-managing provides more choice and control, it requires strong administrative skills and a great amount of time, which not all interviewees had.

For the other half who did not self-manage, choice and control were compromised, as NDIA-managed packages can only be used for a subset of providers. In this context, there is a trade-off – either people manage the plan themself and have maximum choice and control, however, this requires a great investment of time and energy, or they don’t, which limits their choice and control but saves them time and energy.

Stage 5: Support consequences

5a. Demand side – “Ability to engage” and 5b. Supply side – “Appropriateness”

5a. Demand side – The “ability to engage”

The fifth and final demand side ability of the original framework is the ability to engage, which refers to a participant’s capacity and motivation to engage with treatment and care, and to be involved in treatment decision making. As Levesque et al. (Citation2013, p. 6) explain: “access to optimal care ultimately requires the person to be fully engaged in care and this is seen as interacting with the nature of the service actually offered and provided.” For people who use challenging behaviour, engaging with therapeutic supports such as behaviour support is not simple. An uncritical interpretation of participants’ challenging behaviours may be that they function as barriers to engaging with therapeutic supports. However, challenging behaviours often function as a means of communicating and getting needs met (Carr et al., Citation1994; Emerson & Einfeld, Citation2011). Behaviour support aims to increase a participant’s capacities, including the capacity to engage with support people and activities that enhance their quality of life, and meet the persons’ needs, which in turn may reduce challenging behaviour (Emerson & Einfeld, Citation2011). It is, therefore, more relevant to consider the extent to which therapeutic approaches facilitate the ability of people with intellectual disability and behaviour support needs and their families to engage with providers of behaviour support services in the NDIS in the context of behaviour support, which is realised through adequate quality and quantity of a service and provider. As would be expected, interviewees reflected that when supports were adequate and met their family member’s needs, the result was a reduction of challenging behaviour:

He’s really well supported. He’s got a lot of activity, a lot of people in his life and he’s settled and his behaviour’s decreased. (Interviewee 1)

An incongruence in the current research findings when applied to the original access model is the placement and extent of “caregiver support.” “Caregiver support” is mentioned in the original framework as a facilitator of engagement (Levesque et al., Citation2013, p. 5). While no detail is given to the scope or depth of this support in the healthcare context, what is implied is a limited conception of caregiver support. In contrast to this, the present research highlighted the extensive support provided by families in managing every aspect of access for their family member with intellectual disability, far beyond merely encouraging and supporting engagement in therapy. All interviewees were involved in a variety of ways in supporting engagement for their family member, from direct, unpaid, in-kind support work, to managing, training, and educating other support workers, and troubleshooting and overcoming challenges with therapeutic engagement, which had not changed with the introduction of the NDIS.

5+, Beyond “appropriateness,” complex support access requirements

The data in this study shows that adequate access to behaviour support was not always realised, even for families who had progressed through all five stages of the Levesque et al. (Citation2013) framework. That is to say, even after successfully perceiving, seeking, reaching, paying for and engaging with therapy, which meant engaging a behaviour support practitioner and having a behaviour support plan in place, interviewees reported that, in many instances, the therapeutic supports in the behaviour support plan were not being carried out, as many workers were unable to engage with this aspect of a participant’s care. Furthermore, behaviour support plans were more usually just filed away. As one parent explained:

I [asked], “Who’s read the behaviour support plan?” Half […] put their hand up. And I go, “Where is it now?” And they go, “Filed.” (Interviewee 13)

While it is true that behaviour support plans are often very long and very detailed (Chen Fisher et al., Citation2022), simply writing a behaviour support plan is not equivalent to providing behaviour supports. Engaging with, monitoring and reviewing behaviour progress are key parts of behaviour support services (Dowse et al., Citation2017). Given consistency is a key element, interviewees expressed concern about the lack of a consistent implementation and monitoring as well as the ability of disability support workers, who are the most frequently in contact with their family member, to follow the plan:

I hope the psychologist would be able to actually do observation sessions that would be able to pick up why a particular staff member has so many problems with her. (Interviewee 5)

Where the behaviour support practitioner was engaged in monitoring the implementation of therapeutic supports, better outcomes were achieved:

So now [the behaviour support practitioner] is delivering [the plan] to staff in team meetings and [is] very contactable. If there’s an incident, [the behaviour support practitioner says] “Right, let’s go back into the house and make sure what was around and who was on.” (Interviewee 8)

This lack of regulation is of particular concern in the NDIS private provider market (Bould et al., Citation2023), where many workers are independent contractors. Correspondingly, interviewees spoke about problems with support workers who lacked the skills to be effective members of the behaviour support team. Family members who have the capacity, time and resources then oversee this responsibility.

Interviewees thus spoke of the activities they undertook themselves to manage the team of providers:

I’ve got to arrange a meeting, the behaviour support practitioner, when can we have meeting? When can the workers come? When can everybody come? What do we do after meeting? How do we implement? How do we monitor it? It’s exhausting. (Interviewee 1)

It’s a huge multidisciplinary team, they’re amazing. […] This is where I struggle with NDIS, because I have been his informal support coordinator his whole life. I know what each one does. They all work together. I update them, so when I email, I email in bulk. (Interviewee 6)

Some interviewees even trained their support workers, or created their own training materials:

Who’s supporting them to write some social stories? [telling my son and the people he lives with:] “You all no longer go to the day program. The day program staff will come to your house instead.” Like it’s not that hard. But they just don’t think they need to do it and then they wonder why people jack up because things are different. Well, they [the participants] didn’t know they were going to be different. How would you feel if somebody changed your day without telling you? You wouldn’t like it. I do a lot of training with group home workers in this area and I’ve designed the training in a particular way that the penny drops. (Interviewee 1)

Some interviewees had implemented communication strategies to manage information across the team of support workers, such us setting up Facebook or email groups to share information. Many provided unpaid support work and acted as coordinators of support strategies when problem-solving new challenging behaviour.

This highlights the level of expertise of family members (Dreyfus & Dowse, Citation2020) and the need for collaboration between formal and informal supports. In the context of behaviour support, this data clearly shows that ongoing management and oversight of supports are critical to successful realisation of that support.

5b. Supply side – Appropriateness

Appropriateness encapsulates the correct fit of a service to a person’s needs and the time and care spent determining both a person’s needs and the best treatments to meet them. Elements of appropriateness identified in the Levesque et al. (Citation2013) framework and relevant to the behaviour support context include time spent in assessment and planning, the technical and interpersonal quality of the service provider, and the continuous and integrated nature of service provision. We examine these in turn in relation to our data.

Time spent in assessment and planning

The time spent in assessing and planning proved to be an issue for interviewees because there is a requirement for behaviour support plans to meet certain standards set by the Quality and Safeguards Commission (QSC), particularly when there are restrictive practices in place (NDIS Quality and Safeguards Commission Citation2021a). Interviewees often reported that this used up much of the allocated resources for behaviour support and meant the support itself was not always implemented: While the Levesque et al. (Citation2013) framework suggests that “time” refers to too little time spent with a patient and rushed assessments, for some of our interviewees, too much time was spent on developing the plan and not enough time implementing, monitoring, and revising it:

We’ve got precious little time for [the behaviour support practitioner] to make any recommendations […] Because there are some restrictive practices with [my daughter’s] behaviour intervention plan, he might get caught up in paperwork and there will go the last several hundred dollars meeting the demands of the [QSC]. (Interviewee 5)

Because disability providers such as behaviour support practitioners charge hourly, time spent in assessment and planning therefore interacts with the ability to pay, as adequate allocation of funded hours to meet the requirements for effective behaviour support is not available when many of those hours are used up on assessment and planning. This indicates that this is an important factor to consider in NDIS assessments of support efficacy, as reported on in other studies (e.g., Chen Fisher et al., Citation2022).

Interpersonal and technical quality of the service provider

The data revealed that there was a diversity of experience around the quality of the behaviour support practitioner and the behaviour support service. When a behaviour support plan was effectively implemented, some interviewees reported positive experiences and improvements for their family member. However, for others, when the whole team of people who supported their family member were not adequately trained to administer, engage with or support interventions, the result was inconsistent therapy and poorer behaviour outcomes, as evidenced in other studies of behaviour support (e.g., Chen Fisher et al., Citation2022). As discussed, many interviewees spoke of challenges getting support workers to engage appropriately with their family member, especially when needing to use alternative communication methods, which limited social engagement and depth of relationship between support workers and clients, many of whom are non-verbal.

Many also spoke generally about a lack of care and/or interpersonal skills from support workers, with an attitude of:

… get the shift done and go home. They don’t really care that much about what they’re doing, some of them. (Interviewee 11)

Stage 6: Long-term support access

6a. Demand side – “Ongoing support access” and 6b. Supply side – “Ability to maintain”

This new Stage 6 category of “Long-term support access” was necessary to build into the model because the Levesque et al. (Citation2013) stage 5 category of “Support consequences” does not constitute realised access for people with behaviour support needs. This is because behaviour support needs change across a person’s lifetime, depending on a range of factors (Emerson & Einfeld, Citation2011). As already discussed, successful behaviour support requires long-term ongoing engagement, with cycles of frequent monitoring and revision, often over years. Thus, a framework of access to adequately support people with intellectual disability who use challenging behaviour must factor in the appropriate length of time of these supports. For people with ongoing behaviour support needs, access must be continuous across the life course (Dowse et al., Citation2017). Interviewees spoke of the mismatch between discrete packages of treatment and their family member’s need for continuous support. Such NDIS packages are typical among allied health providers, who often provide behaviour support and related services:

But the trouble is with speech therapy, you know the attitude is, “Well you’ve had speech therapy, there’s a program there and that’s the end of it.” (Interviewee 5)

Interviewees were also worried that their annual NDIS funding review process could result in a reduction in funding if their family member’s behaviour support needs happened to be lower in the preceding year, which could represent a risk to the well-being of NDIS participants and their families:

You’ve got your plan now, things seem to be going okay and then they reduced the money. Whereas I know [my son] being the man he is, things may change. He may, well, as we all do change, but something else might come up, and then I’ve got less funding … even within that year of her developing the plan, he started to smash glass. (Interviewee 8)

This issue is further exacerbated by the above-mentioned lack of availability of appropriate support workers, which is critical for maintaining a good life for people with intellectual disabilities who use challenging behaviour (Dowse et al., Citation2017). For one interviewee, despite having allocated NDIS funding, a lack of available support workers meant their family member appeared to not be using their full funding package. This resulted in a reduction in their funding, despite their needs remaining the same. Many described being afraid of losing funding in future years, where any underutilisation was due to challenges of access rather than lack of need:

We haven’t spent much of it in the last year or two, but hopefully they will continue to be as generous with [my daughter] because if you don’t spend it, it just gets reabsorbed of course. But we hope that we will get to use more carers in the next year. (Interviewee 7)

In addition to this, barriers along the chain of access can trigger a need to re-seek support. For example, where families were not able to pay because the NDIS funding offered to them was inadequate, they advocated for more funding. Where services were not available, they re-started seeking a service provider contract by adding their names to waiting lists.

In addition to the challenge of engaging a behaviour support service, many struggled to retain disability support staff who were typically casually employed or contract workers. This led to discontinuity of behaviour support and poorer outcomes for their family member. However, for one interviewee who self-managed their funding package, continuity of support was achieved by her providing free labour to coordinate behaviour support services. This enabled her to retain staff because she was able to pay them more and offer sick leave using the funds saved by her unpaid coordination work:

Well, if they need time off, like one of them is moving house yesterday, but we’ll still pay them … By doing it myself and our family doing it … the money we save, we’re able to pay better wages and have better conditions for our workers. (Interviewee 4)

In this way, beyond the ability to pay that is enabled through the NDIS, the ability of parents to compensate with their own finances or “in kind” work buffered issues of quality (stage 5) and enabled continuous support, for this ongoing access requirement (stage 6), highlighting the interactions between different stages of access.

Concluding discussion

This paper has deployed and adapted the Levesque et al.’s (Citation2013) model of access to examine the effect of the NDIS on access to behaviour support for families who have a member with intellectual disability who uses challenging behaviour. In applying Levesque et al.’s model to this particular disability context, we were able to unpack and make visible the different dimensions of access and determine the extent to service providers were able to fulfil their side of the access process (supply) with regard to behaviour support. The model also enabled us to examine the attributes that NDIS participants and their families need in order to be able to achieve access to behaviour support from their side (demand).

The findings of this analysis show that from the participant side, the financial aspect of access to behaviour support (and supports more broadly) was predominantly achieved through the NDIS, however, it was across other areas of access that there was more diversity of experience; those who self-managed had more choice, control and flexibility to pay and retain workers due to their high level of involvement, oversight and management of their allocated funds. In a sector where there is a high turnover of care staff (Still, Citation2022; Dreyfus & Dowse, Citation2020), being able to retain good workers who can implement behaviour support practices is a challenge. However, the findings also showed that for most of the interviewees, managing their family member’s support services was just as involved and time-consuming as it was when they were first interviewed in 2016, prior to the rollout of the NDIS (Dreyfus & Dowse, Citation2020).

Additionally, while the interview questions focused on access to behaviour support specifically, all participants spoke broadly about issues of accessibility and effectiveness not only regarding their behaviour support practitioner, but to the whole team of supports surrounding their family member, including disability support workers, transportation, housing, support coordinators/coordination, and the process of funding allocation. This reflects that all these elements are interconnected for people with intellectual disability who use challenging behaviour and their families and that one cannot view access to behaviour support without considering access more holistically (Carr et al., Citation1994; Dowse et al., Citation2017; Emerson & Einfeld, Citation2011). Further, this approach is in line with best practice behaviour support (see e.g., Dowse et al., Citation2017), which promotes a holistic view of the person and their total environment when considering a person with behaviour support needs. In other words, to ensure success, behaviour support needs to be addressed across multiple contexts (Dowse et al., Citation2017), and in the present research, interviewees spoke at length about disability support workers’ varying abilities to follow through with behaviour support plans generally and across contexts.

Regarding the families and their abilities and attributes, specifically they were able to perceive, seek, reach and support their family member to engage with supports, with “the ability to pay” being facilitated by the NDIS. However, major issues faced by many families included a lack of service availability, variability in the quality of supports and an inability to pay for adequate treatment as funding was not adequate for comprehensive behaviour support, which includes planning, monitoring, overseeing and reviewing (Dowse et al., Citation2017). The families reported a failure to access quality services and emphasised the challenge of having their behaviour support practitioner engage with their family member for an adequate amount of time due to the thin market of behaviour support practitioners (Dew, Citation2022). This represents a failure in achieving the NDIS outcome of “choice and control,” as there is an insufficient number of providers to choose from and the choice to engage with a service of inadequate quality cannot constitute true “choice.” Further, access is obviously unachievable when there are not enough behaviour support practitioners.

The parents (in this case mothers) from this study whose family member was able to access adequate support did so because they compensated for those barriers on the “supply” side, often providing substantial financial or in-kind support. They devoted considerable extra time, money and expertise to the coordination role as informal support. Their example demonstrates that there needs to be NDIS funding for the role of support coordination in order for the system to be equitable for all participants.

While support coordinators purportedly facilitate access, they are private providers so quality can vary, meaning that rather than safeguarding the process of access, they may prove to be an additional issue for access. As support coordination is not a guaranteed provision for all NDIS participants, the process of accessing a support coordinator is another process of access families must go through.

The access framework was used to identify barriers along the “demand” side axis and ways service users can be better supported to overcome those barriers. In the present study, few barriers in those capacities were found. Rather, it was the systemic problems associated with the provision of services that barred access to supports, despite the fact that funding was available.

While the Levesque et al. (Citation2013) framework was a useful tool for understanding many facets of access, the present study revealed that for people who require a suite of supports, oversight and coordination of those supports are a necessary and ongoing component of access. This remains relevant after the introduction of behaviour support services in the NDIS (see Dreyfus & Dowse, Citation2020).

This is conceptualised in our revised model as an additional facet to stage 5 “service appropriateness,” incorporating management and oversight factors that ensure supports are effectively managed for the whole support of the person with a disability.

Furthermore, when applied to lifelong disability, access is not “realised” by one initial engagement with supports but is, instead, constituted by ongoing arrangements and engagements. We thus expanded the model to stage 6 to take into consideration the important dimension of ongoing access to behaviour support. This additional stage highlights the challenges of maintaining support, including where barriers at other stages may prevent a person from accessing support temporarily and require them to begin the access process again. From the supply side, the market needs to have enough providers available to appropriately provide continuous service. The actions of retaining and seeking care could also be subsumed under the support coordination role, with a greater understanding of the challenges of accessing lifelong support needs. Thus, in the disability support context, support coordination is a possible facet of ongoing support access.

One of the reasons the Levesque et al. model is valuable is because responsibility for problems of access can tend to be focused on demand side deficits in the people seeking support, rather than supply side deficits in service accessibility (O’Keeffe & David, Citation2022). This is especially relevant to vulnerable populations such as people with disabilities, where in a service system that relies on consumers to articulate their needs and access support, “blame” for any problems of access can be placed onto the demand (person) side, which can obscure that the actual issue is accessibility on the service side. In the case of the present study, we interviewed a group of highly competent, engaged and disability-literate parents, and they still had challenges with access to behaviour support. Therefore, it is important to carefully consider which side of the supply/demand divide the problems of access are located, which also frames the responsibility for addressing them. Interviewees were also heavily involved in supporting their family member in accessing essential supports, but for families of people who sometimes use challenging behaviour, the outcomes of support affect the whole family. As such, the family’s role bridged both axes of the framework, being both recipients and providers of support.

As our aim was to investigate the extent to which families had been able to successfully access behaviour support under the NDIS, the delineated framework was useful in understanding the differences in the two axes. In examining the role currently performed by families in providing support and enabling access, we have highlighted the way families compensate for the shortcomings of the marketised environment under the NDIS. Successful access is only achieved by families who have the necessary skills and time to manage and maintain complex supports (Dreyfus & Dowse, Citation2020). This raises questions about the responsibilities of support provision, which is obscured in the new NDIS system that only provides access to supports, not the actual supports themselves, and places the responsibility for successfully following the access process onto the person seeking support.

Limitations and future directions

While this study drew its data from people living in four states across Australia, the data set is small and perhaps thus not representative of the experiences of all NDIS participants who use challenging behaviour and their families. Further, we did not include the voices of people with intellectual disability and challenging behaviours themselves, even though this is encouraged by other researchers in this sector (see e.g., Nind & Strnadova, Citation2020). Rather we interviewed their proxies, who advocate for them, who perceive, seek and manage their supports. It could also be useful and illuminating to re-interview these families again, to see if anything has changed. A possible time to do this could be after any recommendations from the NDIS review (NDIA Citation2021) and the Disability Royal Commission (Citation2023) have been implemented.

This expanded theoretical model, which takes into account long-term engagement with and management of services may be more broadly applicable not only in disability support, but in health care for people with complex illnesses who require an ongoing suite of healthcare services because it considers the ongoing tasks of maintaining access. Importantly, this adapted model has helped to better understand how funded NDIS services are accessible or not to people with intellectual disability and their families. There is scope to consider broader application of this adapted model to other disability service contexts.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 People who receive support under the NDIS are referred to as NDIS “participants,” therefore the participants in this study will henceforth be referred to as “interviewees.”

2 Skimming refers to scrolling through social media information to seek the contact details of a suitable provider.

References

- Barr, M., Duncan, J., & Dally, K. (2021). Parent experience of the National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS) for children with hearing loss in Australia. Disability & Society, 36(10), 1663–1687. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2020.1816906

- Beck, C. T. (1993). Qualitative research: The evaluation of its credibility, fittingness, and auditability. Western Journal of Nursing Research, 15(2), 263–266. https://doi.org/10.1177/019394599301500212

- Beqiraj, L., Denne, L. D., Hastings, R. P., & Paris, A. (2022). Positive behavioural support for children and young people with developmental disabilities in special education settings: A systematic review. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1111/jar.12989

- Bould, E., Sloan, S., & Callaway, L. (2023). Behaviour support for people with acquired brain injury within the National Disability Insurance Scheme: An Australian survey of the provider market. Brain Impairment, 474–488. https://doi.org/10.1017/BrImp.2022.10

- Carr, E. G., Levin, L., Mcconnachie, G., Carlson, J. I., Kemp, D. C., & Smith, C. E. (1994). Communication-based intervention for problem behaviour: A user's guide for producing positive change. Paul H. Brookes.

- Chen Fisher, A., Jarvis, C., Bellon, M., & Kelly, G. (2022). The accessibility and usefulness of positive behaviour support plans: The perspectives of everyday support people in South Australia. International Journal of Positive Behavioural Support, 12(1), 36–45.

- Cortese, C., Truscott, F., Nikidehaghani, M., & Chapple, S. (2021). Hard-to-reach: The NDIS, disability, and socio-economic disadvantage. Disability & Society, 36(6), 883–903. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2020.1782173

- Council of Australian Governments. (2010). The National Disability Strategy. Commonwealth of Australia.

- Crabtree, B. F., & Miller, W. L. (1992). A template approach to text analysis: Developing and using codebooks. In Benjamin F. Crabtree & William F. Miller (Eds.), Doing qualitative research (pp. 93–109). Sage.

- Dew, A. (2022). What, if anything, has changed over the past 10 years for people with intellectual disabilities and their families in regional, rural, and remote geographic areas? Research and Practice in Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 9(2), 103–107. https://doi.org/10.1080/23297018.2022.2109195

- Dowse, L., Hogan, L., Dew, A., Didi, A., Wiese, M., Conway, P., Dreyfus, S., & Smith, L. (2017). Responding to behaviour needs in the disability services future. https://researchdirect.westernsydney.edu.au/islandora/object/uws%3A44665

- Dreyfus, S., & Dowse, L. (2020). Experiences of parents who support a family member with intellectual disability and challenging behaviour: “This is what I deal with every single day”. Journal of Intellectual & Developmental Disability, 45(1), 12–22. https://doi.org/10.3109/13668250.2018.1510117

- Duignan, M., & Connell, J. (2015). Living with autistic spectrum disorders: Families, homes and the disruption of space. Geographical Research, 53(2), 199–210. https://doi.org/10.1111/1745-5871.12112

- Emerson, E., & Einfeld, S. L. (2011). Challenging behaviour (3rd ed.). CUP.

- Foley, K., Attrill, S., McAllister, S., & Brebner, C. (2021). Impact of transition to an individualised funding model on allied health support of participation opportunities. Disability and Rehabilitation, 43(21), 3021–3030. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2020.1725157

- Foster, M., Henman, P., Tilse, C., Fleming, J., Allen, S., & Harrington, R. (2016). ‘Reasonable and necessary’ care: The challenge of operationalising the NDIS policy principle in allocating disability care in Australia. The Australian Journal of Social Issues, 51(1), 27–46. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1839-4655.2016.tb00363.x

- Gao, F., Foster, M., & Liu, Y. (2019). Disability concentration and access to rehabilitation services: A pilot spatial assessment applying geographic information system analysis. Disability and Rehabilitation, 41(20), 2468–2476. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2018.1468931

- Gavidia-Payne, S. (2020). Implementation of Australia’s National Disability Insurance Scheme: Experiences of families of young children with disabilities. Infants & Young Children, 33(3), 184–194. https://doi.org/10.1097/IYC.0000000000000169

- Hastings, R. P. (2002). Parental stress and behaviour problems of children with developmental disability. Journal of Intellectual and Developmental Disability, 27(3), 149–160.

- Hubert, J. (2011). ‘My heart is always where he is’. Perspectives of mothers of young people with severe intellectual disabilities and challenging behaviour living at home. British Journal of Learning Disabilities, 39(3), 216–224. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-3156.2010.00658.x

- Jessup, B., & Bridgman, H. (2022). Connecting Tasmanian National Disability Insurance Scheme participants with allied health services: Challenges and strategies of support coordinators. Research and Practice in Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 9(2), 108–123. DOI: 10.1080/23297018.2021.1969264

- Johnsson, G., & Bulkeley, K. (2021). Practitioner and service user perspectives on the rapid shift to teletherapy for individuals on the autism spectrum as a result of COVID-19. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(22), 11812. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182211812

- Lakhani, A., Parekh, S., Gudes, O., Grimbeek, P., Harre, P., Stocker, J., & Kendall, E. (2019). Disability support services in Queensland, Australia: Identifying service gaps through spatial analysis. Applied Geography, 110), https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apgeog.2019.102045

- Levesque, J.-F., Harris, M. F., & Russell, G. (2013). Patient-centred access to health care: Conceptualising access at the interface of health systems and populations. International Journal for Equity in Health, 12, 18. http://www.equityhealthj.com/content/12/1/18

- Loadsman, J. J., & Donelly, M. (2021). Exploring the wellbeing of Australian families engaging with the National Disability Insurance Scheme in rural and regional areas. Disability & Society, 36(9), 1449–1468. DOI: 10.1080/09687599.2020.1804327

- Maes, B., Broekman, T. G., Došen, A., & Nauts, J. (2003). Caregiving burden of families looking after persons with intellectual disability and behavioural or psychiatric problems. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 47(6), 447–455. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2788.2003.00513.x

- Matin, B. K., Williamson, H. J., Karyani, A. K., Rezaei, S., Soofi, M., & Soltani, S. (2021). Barriers in access to healthcare for women with disabilities: A systematic review in qualitative studies. BMC Women’s Health, 21(1), 44–23. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-021-01189-5

- National Disability Insurance Agency. (2021). Annual report 2020–21. https://www.ndis.gov.au/about-us/publications/annual-report

- National People with Disabilities and Carer Council. (2009). Shut out: The experience of people with disabilities and their families in Australia. Commonwealth of Australia. https://www.dss.gov.au/our-responsibilities/disability-and-carers/publications-articles/policy-research/shut-out-the-experience-of-people-with-disabilities-and-their-families-in-australia

- NDIS Quality and Safeguards Commission. (2021a). Behaviour support. https://www.ndiscommission.gov.au/providers/behaviour-support

- Ng, J., & Rhodes, P. (2018). Why do families relinquish care of children with intellectual disability and severe challenging behaviours? Professional’s perspectives. Qualitative Report, 23(1), 146–157.

- Nind, M., & Strnadova, I. (2020). Belonging for people with profound intellectual and multiple disabilities: Pushing the boundaries of inclusion. Routledge.

- O’Keeffe, P., & David, C. (2022). Discursive constructions of consumer choice, performance measurement and the marketisation of disability services and aged care in Australia. Australian Journal of Social Issues, 57(4), 938–955. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajs4.139

- Phillipson, L., & Hammond, A. (2017). Use of support services by carers of older people from CALD backgrounds: A review of abilities which support accessibility of support services in Australia. Australian Health Services Research Institute, University of Wollongong.

- Productivity Commission. (2011). Disability care and support (Report no. 54). https://www.pc.gov.au/inquiries/completed/disability-support/report

- Prowse, A., Wolfgang, R., Little, A., Wakely, K., & Wakely, L. (2022). Lived experience of parents and carers of people receiving services in rural areas under the National Disability Insurance Scheme. Australian Journal of Rural Health, 30(2), 208–217. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajr.12837

- Roberts, K., Dowell, A., & Nie, J. B. (2019). Attempting rigour and replicability in thematic analysis of qualitative research data; A case study of codebook development. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 19(1), https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-019-0707-y

- Royal Commission into violence, abuse, neglect and exploitation of people with disability. (2023). Seventh progress report. https://disability.royalcommission.gov.au/publications/seventh-progress-report

- Sailor, W., Dunlap, G., Sugai, G., & Horner, R. (2009). Overview and history of positive behaviour support. In W. Sailor, G. Dunlap, G. Sugai, & R. Horner (Eds.), The handbook of positive behaviour support. Springer.

- Smethurst, G., Bourke-Taylor, H. M., Cotter, C., & Beauchamp, F. (2021). Controlled choice, not choice and control: Families’ reflections after one year using the National Disability Insurance Scheme. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal, 68(3), 205–216. https://doi.org/10.1111/1440-1630.12715

- Still, F. (2022). Factors affecting disability support worker retention within the disability sector. NDS. https://www.nds.org.au/resources/all-resources/understanding-key-factors-that-impact-disability-support-worker-retention

- Totsika, V., Toogood, S., Hastings, R. P., & Lewis, S. (2008). Persistence of challenging behaviours in adults with intellectual disability over a period of 11 years. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 52(5), 446–457. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2788.2008.01046.x

- Trounson, J. S., Gibbs, J., Kostrz, K., McDonald, R., & Peters, A. (2022). A systematic literature review of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander engagement with disability services. Disability & Society, 37(6), 891–915. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2020.1862640

- United Nations. (2006). Convention on the rights of persons with disabilities and optional protocol. United Nations. https://humanrights.gov.au/our-work/disability-rights/united-nations-convention-rights-persons-disabilities-uncrpd

- van den Bogaard, K. J. H. M., Lugtenberg, M., Nijs, S., & Embregts, P. J. C. (2019). Attributions of people with intellectual disabilities of their own or other clients’ challenging behavior: A systematic review of qualitative studies. Journal of Mental Health Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 12(3-4), 126–151. https://doi.org/10.1080/19315864.2019.1636911

- Wall, K., Kerr, S., & Sharp, C. (2021). Barriers to care for adolescents with borderline personality disorder. Current Opinion in Psychology, 37, 54–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2020.07.028

- White, C.S., Spry, E., Griffiths, E. & Carlin, E. (2021) Equity in access: A mixed methods exploration of the National Disability Insurance Scheme access program for the Kimberley Region, Western Australia. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(17), 8907. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18178907

- Yates, S., Carey, G., Hargrave, J., Malbon, E., & Green, C. (2021) Women’s experiences of accessing individualized disability supports: Gender inequality and Australia’s national disability insurance scheme. International Journal for Equity in Health 20(1), 1-14. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-021-01571-7

Appendix. Interview schedule

Part 1: Demographic information

Part 2: Experience of behaviour support

Please describe your family’s experience of behaviour support for your member with intellectual disability and challenging behaviour since being in the NDIS. [Interviewer probes for each of]:

History of experience.

Current experience.

Has the NDIS changed the way you receive behaviour support compared to before the NDIS?

Please tell me about the behaviour support services received within the NDIS and the extent to which they met your family’s needs [Interviewer probes for e.g., jargon-free language, matching family lifestyle, accounting for each family member’s needs].

Please tell me about the responsiveness of the behaviour support service you and your family member received or are receiving within the NDIS [Interviewer probes for e.g., whether family got it when needed, where needed, and for sufficient time for it to be helpful]

Did the behaviour support make a difference? [Interview probes for each of the following]:

To the family member with intellectual disability and challenging behaviour.

To each member of the family as well as the family unit as a whole.

What kinds of difference it made.

If it didn’t make a difference, the reasons why.

Would you change the behaviour support service you and your family member have received and if so, how?

Please outline any unmet needs your family has for behaviour support.

Please describe any advice you have about how behaviour support practitioners within the NDIS could do their job better for families like yours.

***Use of psychotropic medication as part of the behaviour support?

Is there anything further about your and your family members’ experience of behaviour support within the NDIS you would like to share with us?

Have you and your family member’s lives changed more generally as a result of being in the NDIS? If so, how?

Has COVID19 had any impact on the wellbeing and behaviour of your family member?

Has COVID19 had any impact on the behaviour support service your or your family member are receiving?