ABSTRACT

Background

People with intellectual disabilities have traditionally been excluded from Advance Care (AC) planning. This study aimed to improve access to and the quality of AC planning for this community.

Method

A Participatory Action Research study was led, and participated in, by co-researchers with intellectual disabilities and disability service managers. A new approach to AC planning was trialled and evaluated.

Results

The new approach aided the initiation and development of comprehensive AC plans with people with intellectual disabilities. The completed plans were approved by health professionals. Contributing factors related to getting started, the materials, and the process.

Conclusion

The emergent framework, developed in response to the findings, provides a potential pathway for implementation and further exploration of AC planning.

Advance Care (AC) planning assists people to think about, plan for, and document what they want to have happen at the end of their lives (Sudore et al., Citation2017). Although there are various definitions of AC planning, most hold that it is a process (rather than a one-off event) that involves thinking and talking about end-of-life, is based on the wishes of the person themselves, and is holistic in nature (not only focused on dying, but on life goals, personal, spiritual, cultural beliefs, and values). Therefore, AC planning aims to make explicit the person’s preferences for how to live well, the future support they want, and their medical care wishes for when they become seriously unwell, or when they are dying.

AC planning in the general population is known to result in benefits such as increased goal-aligned care at end-of-life (Bernacki & Block, Citation2014; Brinkman-Stoppelenburg et al., Citation2014; Detering et al., Citation2010), decreased stress and anxiety (Pino et al., Citation2016; Tan et al., Citation2019), and a minimised sense of burden in relation to serious illnesses (Duckworth & Thompson, Citation2017). Additionally, relatives often feel more confident making decisions on the person’s behalf, and experience reduced levels of stress themselves (Song et al., Citation2015).

Despite there being clear benefits to AC planning, successful implementation remains variable. Within the general population there is significant evidence that initiating and completing AC planning comes with challenges; AC conversations are prone to occur too late, and clinicians find it hard to start such conversations with their patients (Norals & Smith, Citation2015). Although they may have appropriate knowledge, a lack of confidence in talking about end-of-life issues often prevents them from initiating or continuing these conversations (Disler et al., Citation2021; Nagarajan et al., Citation2022). As such, AC planning programmes benefit from being facilitated by trained individuals (Duckworth & Thompson, Citation2017; Goodwin et al., Citation2021) whose roles are clearly defined and who have capacity to undertake the complex discussions that are required over time (Nagarajan et al., Citation2022). AC planning that has a holistic focus is likely to be more successful and satisfying for consumers (Brinkman-Stoppelenburg et al., Citation2014; Rojers et al., Citation2019).

The intellectual disability context

In the last decade, research has been broadly supportive of AC planning with people with intellectual disabilities (Bekkema et al., Citation2014; McKenzie et al., Citation2017; Todd, Citation2013; Tuffrey-Wijne et al., Citation2017; Wiese et al., Citation2015) and there is an emerging body of work related to exploring end of life, dying, and AC planning for this population. Research demonstrates that the issues that impact the efficacy of AC planning for the general population are often exacerbated for people with intellectual disabilities. For example, people with intellectual disabilities are rarely told they are dying (Hunt et al., Citation2020), and their end-of-life decisions are often made late, focus primarily on medical aspects (Voss et al., Citation2019; Wagemans et al., Citation2012; Wagemans et al., Citation2013), and are made largely by substitute decision-makers (Forrester-Jones et al., Citation2017; Grindrod & Rumbold, Citation2017; Wicki, Citation2020). High rates of unexpected deaths in this population (Bernal et al., Citation2021) may not leave sufficient time for quality planning to occur, making pro-active planning (while people are young and well) a potentially important, but as-yet un-researched, activity for this population.

Research directly related to AC planning is slowly emerging and tends to focus on individual components that are, or could be, part of AC planning. This includes studies describing how to disclose bad news to people with intellectual disabilities (Tuffrey-Wijne et al., Citation2013), training staff to communicate about death and dying to people with intellectual disabilities (Tuffrey-Wijne et al., Citation2017; Wiese et al., Citation2015), and the use of Advance Directives (ADs) (Wagemans et al., Citation2017).

To date, only a small number of studies have sought to explore the whole process of developing and documenting AC plans (McKenzie et al., Citation2017; Noorlandt et al., Citation2021, Citation2024; Watson et al., Citation2019). McKenzie et al. (Citation2017) explored the perspectives of people with intellectual disabilities involved in their own AC planning process. Though the AC plans that were developed all contained rich detail regarding people’s values, quality of life, decision-making needs and preferences, what was important to them, and their wishes for after death, some omitted details about health treatment preferences and legal matters. Noorlandt et al. (Citation2021) addressed this gap by co-designing, with a group that included people with intellectual disabilities, a tool called In-Dialogue. In-Dialogue is a conversation aid that, among other topics, explicitly addresses health and treatment preferences. The specific content of In-Dialogue is not currently publicly available and as such it is not known if it fully covers all the content usually included in a holistic AC plan, or how well it would translate to use in other jurisdictions. Despite these limitations, both McKenzie et al. (Citation2017) and Noorlandt et al. (Citation2024) evidenced successful outcomes in which individuals with intellectual disabilities developed plans related to their end-of-life wishes, and in which people with intellectual disabilities described the value they saw in being able to explore their wishes, and make their own decisions. This was reinforced by the participants with intellectual disabilities in a study by Voss et al. (Citation2020) who identified that their role in AC planning would be that of the decision-maker. McKenzie et al. (Citation2017) and Noorlandt et al. (Citation2024) both also found that successful involvement in end-of-life decision making was influenced by the following factors: planning progressing at each person’s pace and being facilitated face-to-face by someone who knew the person well; and, materials (such as learning resources on various topics, and the AC plan template) being adapted to aid understanding and decision making. Both authors found that the process could be challenging for facilitators, with Noorlandt et al. (Citation2024) indicating that good support from colleagues helped with this. Crucially, both authors (McKenzie et al., Citation2017; Noorlandt et al., Citation2024) also noted the advantages of starting as early as possible, indicating that waiting until a person is seriously unwell could make it difficult for conversations to take place. In a departure from the above studies, which focused on people who were able communicators, Watson et al. (Citation2019) used a narrative storytelling approach with an individual who had significant intellectual disability and complex communication needs, to determine the person’s will and preference at end-of-life. This provided evidence of a different pathway to recognise the wishes of people whose communication is less intentional or more difficult to interpret, but due to the small scale of this study, further exploration is warranted.

The studies described above have contributed to the developing evidence-base regarding how AC planning can be approached for people with intellectual disabilities. Additionally, co-design studies, such McKenzie et al. (Citation2017) and Noorlandt et al. (Citation2024) demonstrate a way to explore such topics, while prioritising what is important to people with intellectual disabilities. However, there remains limited evidence regarding how to initiate AC planning with this population, whether or to what extent pro-active planning assists in this regard, how to ensure that the tools used meet the needs of people with intellectual disabilities while also fully covering the necessary content, and how to engage people who have significant intellectual disabilities.

The current study

To begin addressing the gaps noted in the background information above, this study aimed to answer the question, “what factors enable people with intellectual disabilities to access and participate in the development of their own Advance Care (AC) plans?”

The specific aim for cycle three was to implement and evaluate the tools and processes that had been developed in earlier cycles of the study (as outlined below), thereby providing a comprehensive response to the research question.

Method

Research design

The study utilised Participatory Action Research (PAR) methodology, an approach whereby researchers partner with individuals from the community of interest. Members of the community of interest are involved in any/all aspects, and may act as a study’s co-researchers while also being its participants (Mertens, Citation2009; Swantz, Citation2013), as was the case in this study. Specific methods, which evolve throughout the study, are determined and directed by the co-researchers, with assistance and guidance from experienced researchers, enabling responsivity to emerging issues (Mertens, Citation2009). This methodology was chosen because it prioritises the perspectives and views of the community of interest, and because of its focus on co-research and co-design. These principles aligned well with the objective of seeking practice transformations that would be successful for people with intellectual disabilities (the community of interest).

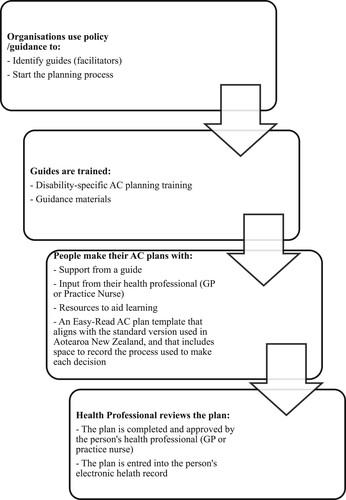

Although this article focuses on the outcomes of the third of three cycles in this study, a brief explanation of the whole study is provided to orientate readers and provide necessary contextual information. During cycle 1, a co-research group of people with intellectual disability (co-researchers with intellectual disabilities) and managers from their residential intellectual disability services (manager co-researchers), who were also the study’s participants, led a review of the current AC planning process in Aotearoa New Zealand. They identified the ways that this could be improved to better meet the needs of people with intellectual disabilities. A new approach was designed (), and during cycle 2 the materials to support this were developed. Materials included; an Easy-Read information pamphlet, a policy guide for service providers, an Easy-Read AC plan template called “My plan for a good life, right to the end,” an education workshop for guides, and a guidebook to help supporters with implementation. The Easy-Read plan template aligned with the standardised version of the AC plan that is used in Aotearoa New Zealand, called “My advance care plan and guide” (Health Quality and Safety Commission, Citation2018), because the Health Professionals involved in earlier cycles indicated that this would enable them to upload completed plans to people’s on-line health record and therefore assist with implementation at end-of-life. Crucially, the Easy-Read plan also included features such as colour-coded sections, room to draw or add photos, and spaces to record how decisions were made (to evidence supported decision-making practices). The Easy-Read plan template, guidebook for supporters, and policy guide can be accessed at https://www.understandable.org.nz/advance-care-planning During cycle 3, the new approach and materials were trialled and evaluated, with improvements being made throughout the cycle in direct response to data.

In cycle 3 each of the co-researchers with intellectual disabilities chose someone to support them with developing their plans (a manager co-researcher or senior staff person from their disability service). They rereferred to this person as the “guide.” The guides all completed an interactive on-line training session to prepare them for their role. The training took approximately 4 hours and could be completed whenever suited each guide. The training content included: the purpose and benefits of AC planning; legal aspects of capacity and consent relevant to AC planning in Aotearoa New Zealand; exploring accessible tools and resources to aid learning and decision-making on various topics; and, how to record (including using “My plan for a good life, right to the end”) and share decisions. Following training, the guides supported the co-researchers with intellectual disabilities to explore, learn about, consider, and document their wishes (alongside family members, as agreed), utilising tools and approaches that met each person’s individual communication needs and preferences. Guides supported each person to discuss their plan with their primary health care professional, to have their plan approved and uploaded to their electronic health record, and to share the plan with others as wished.

Participants

The co-research group was involved for all 3 cycles. They were recruited from 3 community residential intellectual disability services (disability services) in the Waitaha Canterbury region of Aotearoa New Zealand. The co-researchers were actively involved as both directors of the study and as the study participants, as is usual within PAR studies. The co-research group (details in ) comprised of:

7 Pākehā (European New Zealanders) adults with intellectual disabilities (co-researchers with intellectual disabilities), aged between 45 years and 86 years at the start of the study, who could take part in conversations, and who had an interest in AC planning. A separate recruitment process was designed and implemented, with support from a skilled cultural advisor, to recruit tāngata whaikaha Māori (indigenous New Zealanders with intellectual disability) as co-researchers. However, recruitment of tāngata whaikaha Māori was unsuccessful.

4 managers (manager co-researchers), from the involved disability services, who had an interest in AC planning. There were some changes within this group throughout the study.

Table 1. Cycle 3 co-researcher and participant list.

Several other participants were involved in cycle 3 (see ), including family members, disability professionals (additional to the manager co-researchers), and 1 health professional. The co-researchers with learning disabilities could opt to invite family members to take part as participants. Three co-researchers with intellectual disabilities invited family members to take part. Two family members consented to take part and remained involved through all 3 cycles. One invited family member did not respond to messages regarding the invitation and did not take part. For this cycle an additional 3 senior disability professionals were recruited to the study. Along with the manager co-researchers, they each acted as guides. In addition, the co-researchers with intellectual disabilities invited their General Practitioner (family doctor) or Practice Nurse to provide feedback on their involvement with their AC plan. This was another challenging aspect of recruitment, with multiple attempts made to contact health professionals. One health professional consented to take part.

Data collection

Data related to materials and process were treated in different ways, though each involved the collection of feedback from users. In keeping with the study’s action-oriented approach, recommended changes were made promptly to materials and process so that improved versions could continue to be used and evaluated.

Data regarding materials was gathered via interviews and interactions with guides. Data related to process was collected in a range of ways. Critically, there was regular contact between the researcher, co-researchers with intellectual disabilities, guides, and family member participants throughout the trial, including: semi-structured interviews with co-researchers with intellectual disabilities and participating family members; a mid-way meeting with the manager co-researchers; semi-structured interviews with all involved at the end of the trial (including the health professional participant); and a co-research group meeting at completion of the cycle.

Planned contacts, such as co-research group meetings and interviews, were audio-recorded and transcribed. Audio data files were transferred to a password protected computer and transcribed verbatim within a few days of the recording. Research notes were kept for informal contacts, such as unexpected phone calls or email feedback. Data were anonymised but care was taken to ensure that this did not distort meaning. Collection of data related to identified topics stopped only when no new ideas or themes arose on each topic of discussion.

Data analysis

Data were coded according to Braun and Clarke’s (Citation2006) method. Codes were named using language that came from the co-researchers themselves, thereby capturing their perspective in an authentic way. The researcher utilised theoretical knowledge about AC planning and intellectual disability to identify key ideas from the data set, while being open to new and unexpected ideas. As such, the coding labels evolved over time, reflecting a conscious process of being reflexive in response to the data.

Care was taken not to make assumptions or impose meaning where none existed and codes were developed for ideas or concepts that re-occurred, or that had significance or intensity, where there were patterns or meanings linked to social/theoretical concerns, and where there was agreement or disagreement among individuals. A member-checking and review process embedded within co-research group meetings, provided multiple opportunities to check interpretations. Codes were recorded in a code definition log and were applied to all data fragments. Coder variance was addressed by having the research team code various segments of data and compare results. All coders were closely aligned.

Data codes were then explored to identify central organising concepts, as recommended by Braun and Clarke (Citation2019). Where clear linkages were identified, individual codes were grouped together into four key themes, which are discussed in the results section below.

Ethical approvals

The study was approved by the University of Otago Human Ethics Committee (H18/051). Several potential ethical issues were identified as relevant to the study, including: the involvement of people with intellectual disabilities; managing distress; engaging with Māori (indigenous people of Aotearoa New Zealand); protection of co-researcher rights; privacy and confidentiality; and the provision of donations to thank primary health care services for their involvement in evaluation. Plans for managing these issues were included in the study’s initial ethics application, and in 3 subsequent applications as the study evolved. All applications were approved.

Results

The following section presents the results of the implementation and evaluation of the new approach to AC planning, which was developed in earlier phases of the study. Findings are separated into those related to getting started (initiation), the evaluation of materials, and the evaluation of process. Each of these is discussed below.

Getting started

Getting started with AC planning was, for the co-researchers with learning disabilities, assisted by their investment in the topic and the expert level of knowledge they acquired through their involvement in the study. However, the co-research group identified additional factors that they thought had helped them, and that may help others, to initiate an AC planning process. These included having ongoing conversations about death and dying and AC planning so that the topic was normalised, having someone trusted to ease the concerns of family members and build trust in the AC planning process, and having organisational policy related to AC planning. Manager co-researchers particularly saw policy as both a means to promote AC planning and to create an organisation-level expectation that it would occur.

Materials

The trialled materials were well-received, and only small changes were made to most documents. Feedback largely related to the Easy-Read AC plan template, titled “My plan for a good life, right to the end.”

The co-researchers with intellectual disabilities found that the Easy-Read AC plan template suited their needs and preferences. As Katherine commented:

Um no, I wouldn’t be able to read the writing, no, but I can follow the pictures. (Katherine, co-researcher with intellectual disability)

The guides all commented that the plan template worked well for them and the people they supported, while providing a straight-forward means for exploring and recording people’s decisions:

It’s all been flowing really beautifully, and it feels nice, like there are nice segments to it. I don’t know how it feels when you are doing it, but there are nice pauses, natural pauses. (Penny, manager co-researcher and guide)

Additionally, the one participating health professional found it helpful that the plan template aligned to the standardised version that they were familiar with (Health Quality and Safety Commission, Citation2018). Guides also reported that other health professionals said that they valued the way that decision-making practices were documented, as this gave them guidance on how to check decisions, and consolidated their trust in the plan:

The GP was really pleased … what we had written was exactly what she [Joan] said, so they were more than happy, and it was all signed and done. (Debra, manager co-researcher and guide)

The guides played an important role in supporting the co-researchers with intellectual disabilities to understand each content area, and in making adaptations to suit the needs of each person. For example, Andrew’s guide responded to his preferences by converting his plan into a document that could be “read” aloud by a screen-reading application on his computer.

Process

Of the 7 co-researchers with intellectual disabilities, 5 completed AC plans and shared these with their health professional within the study timeframe. Michael’s plan was completed after the study finished. Katherine completed her plan but wished to share it with her family prior to meeting with her GP, and asked for this to be delayed due to a family bereavement. Key themes related to the AC planning process are described below and include “getting it done,” “getting it right,” involving my family,” and “outcomes.”

Getting it Done. In the plans that were completed within the study, all content areas were fully addressed. Analysis identified several key actions that helped to get AC planning done. This included; confirming a guide (the right guide, which required having enough time, being trained, and knowing the person well), scheduling time to talk and meet, and using the developed materials. Each was an important contributor to getting the planning process started and finished:

Yeah … good planning is how you get things done. So, if I put in my diary that each time each week I was going to meet somebody, it would just be another appointment that I need to work around. Good planning would do it. (Helen, manager co-researcher and guide)

Getting it Right. The theme “getting it right” refers to the actions of the guides and supporters that contributed to the quality of an AC plan. These included taking enough time, planning ahead, focusing on the person (person-centred), using a learning-first approach, gathering rich and detailed information, and revisiting/reviewing/clarifying content:

Yeah, it took a bit longer than planned, but we just had to be careful. We didn’t want to rush, we wanted to make sure that we did it really really well. (Debra, manager co-researcher and guide)

The analysis category “focus on me” occurred extensively, suggesting that the ability to individualise content and approach was a vital component in successful AC planning. It linked strongly with the analysis category of “learning first,” whereby the guides, who came to the study as experienced teachers and communicators, supported people to learn about each content area before making decisions. They did this using a range of strategies, such as adapting information from websites, simplifying language, presenting images, or watching videos. At times, some co-researchers with intellectual disabilities found content hard to understand and learning opportunities did not result in the person understanding the information well enough to make independent decisions. For example, Katherine learned about the resuscitation options, but still found it hard to make sense of it. She said:

Too hard to understand that [the resuscitation section]. Yep. (Katherine, co-researcher with learning disability)

However, guides were able to draw from Katherine what quality of life meant to her. She vividly and clearly described how she values being busy, active, helping others, and being very involved in her community. People who know her well commented that she probably would not like to be unwell long-term, and gave examples of why they believed this to be the case. These details were recorded clearly so that they could be used to help with making health care and treatment decisions in future. Conversely, Wendy was initially unfamiliar with the various end-of-life treatment options, but after learning about these, using examples from her life and familiar television shows, was able to clearly articulate her wishes and explain why she had made her particular choice.

Guides came to their roles with varying levels of comfort and confidence in discussing end-of-life topics. Some, like Penny, felt happy to progress with minimal support, while others sought more regular or specific coaching or guidance:

Yeah, I felt a bit blind for a bit but then it came right, and I could support Joan. (Debra, manager co-researcher and guide)

I got it completed because I had support. And honestly that’s the truth. (Helen, manager co-researcher and guide)

In response to individualised support from the guides, the co-researchers with intellectual disabilities provided rich and detailed information. Other people (relatives or long-standing support workers) were often able to supplement this information in valuable ways. For example, a support worker with whom Michael had a lengthy history, provided detail about important people from the past, his love of gardening and the outdoors, and other aspects that Michael had not articulated himself.

Involve My Family. The co-researchers with intellectual disabilities made clear decisions about whether and how to involve family members in their planning process. For example, Andrew regularly talked through his thoughts with his family member, using them as a sounding board to help him come to his own decisions:

[It was helpful to send emails after each session] so [they] can see what I’ve been talking about. (Andrew, co-researcher with learning disability)

The co-research group recognised that not everyone would want their family to be involved, and were clear that involvement should only take place if they gave consent for this. As such, Gareth kept his family member up to date with progress, seeking her opinion on specific matters, and Wendy chose not to involve her family member, given their divergent views:

Sometimes Wendy likes to share things with [family member] and sometimes she doesn’t. Because [they have their]own sort of opinions about what should be happening for Wendy, which don’t always match what Wendy wants to do. (Linda, guide)

Guides noted that strong and trusting relationships with family members were important and that this was facilitated by maintaining regular contact, by being transparent, showing that they were focused on the person with intellectual disability, and being open to discussing concerns.

Outcomes. All involved found the process of planning was clear and the tools were easy to use. All guides reported that most of the content was easily navigated, and the conversations were less daunting than they had anticipated:

So far all going well, and relatively straightforward. (Debra, manager co-researcher and guide)

However, the guides also reported that some content areas were challenging for them to initiate and discuss, particularly those related to treatment options, resuscitation, and advance directives. At times they sought support from the researchers and colleagues, and referred to their Guidebook for supporters’ for advice. They did not shy away from difficult topics and supported the co-researchers with intellectual disabilities to explore the options and make their decisions:

Yes, but some things we think are tricky aren’t, like this one [where I want to die] – Joan says she wants to stay here and checked that she doesn’t have to go anywhere else. (Debra, manager co-researcher and guide)

The rich and detailed information that was collected enabled the goal (identified in cycle one) of “capturing the essence of me” to be achieved. For example, Pam commented that her family member, Gareth’s, choices were perfect for him:

It sounds like him. It cracks me up, he’s very funny. I love that he wants to be buried with his DVDs. (Pam, family member)

All of the co-researchers with intellectual disabilities were positive about the usefulness of their plans. They all commented, about specific decisions that they were pleased had been recorded in their plans:

I wrote I want to go to the rest-home when I’m old. Not right now, but when I old. (Wendy, co-researcher with learning disability)

It keeps you safe. (Trish, co-researcher with learning disability)

All of the plans shared with health professionals were approved and uploaded to the person’s electronic health record for future use. Trust in decisions was influenced by factors such as the stability of the decision (being maintained over time), having a clear rationale for the decision, and evidence from daily life or the past that gave weight to their decisions. The “process I followed to make my choice” sections of the plan were reported to be instrumental in helping family members and health professionals to trust the decisions. Comments included:

The doctor was ok with it. (Andrew, co-researcher with learning disability)

It’s so clear and it’s great. I’m very happy with it. (Pam, family member)

Additionally, being involved in AC planning facilitated the development of comfort in talking about death and dying, and in personal growth. “Being comfortable” was noted as both an outcome, and benefit, of being involved in an AC planning process rather than a pre-requisite for starting:

Well, I was reticent, yes, because he’s had a … thing … but it’s turned out beautifully, so thank you. To me it’s been amazing, to open up that path and that mindset. (Terry, family member)

I got more confidence, and then reading the tools, that helped. It was good. (Helen, manager co-researcher and guide)

Discussion

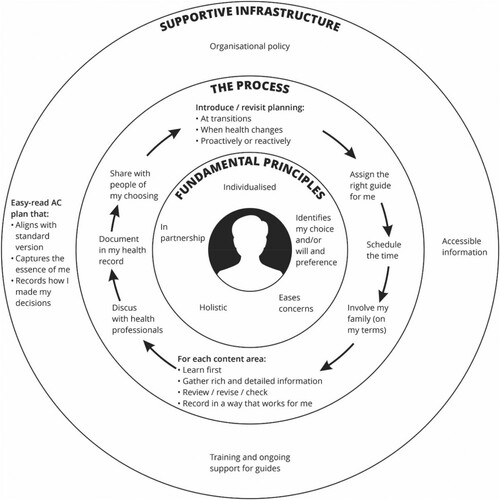

This study focused on AC planning as a whole, from organisational policy, to the development of materials, training of guides, completion of plans, and approval of the plans by health professionals. This was a clear departure from most previous studies which have largely focused on single aspects of AC planning such as ADs (Wagemans et al., Citation2017), or training of staff (Tuffrey-Wijne et al., Citation2017; Wiese et al., Citation2018). Making cohesive sense of the wide variety of factors identified in this study is complex; there is a risk that some components may be seen as more important than others, when in reality they are all inter-connected. For example, although the Easy-Read AC plan template provided a means to record decisions more easily, their use may have been limited without strong individualised support from guides. To illustrate the relationships between components more clearly, the authors have developed an emergent framework ().

Figure 2. Emergent framework: factors supportive of successful advance care planning with people with intellectual disabilities.

Many of the elements that are included in the emergent framework were identified as important by the co-research group in cycle 1, and were then built into the resources that were developed in cycle 2. Analysis of the data gathered during cycle 3 enabled us to confirm which factors contributed to the co-researchers with learning disabilities being able to get started with AC planning and to develop their own comprehensive AC plans.

The inner most layer of the framework relates to the fundamental principles that formed the foundation of the approach. The fundamental principles fed into the next layer, related to the planning process itself, and these in turn influenced the outer-most infrastructural elements that helped successful planning to occur.

Fundamental principles

Central to the success of AC planning within this study was the application of four fundamental principles: individualising the approach so that it met the specific preferences and needs of each person; easing concerns; working in partnership with the person about their plan; planning holistically, and; identifying the person’s own choices and/or will and preference. These principles formed the philosophical backbone of the approach.

Reflection on these principles raises an aspect of significant concern. There is a current disconnect between the rights afforded under Article 12 – Equal recognition before the law of the UNCRPD (United Nations Commitee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, Citation2014) and the provisions of the Protection of Personal Property and Rights Act 1998 in Aotearoa New Zealand, making it unclear how well accepted or legally binding decisions made within a supported decision-making context would be. This may be an issue of relevance on other jurisdictions as well. This issue, though not unique to AC planning, is integral to AC planning, and is necessary to resolve if all people are to have their wishes respected at the end-of-life.

Process of planning

The middle layer of the emergent model presents the process of AC planning. This closely aligns to processes described in the literature related to the general population (Health Quality and Safety Commission, Citation2021; Queensland, Citation2018) but with two key additional components. These components are that learning should be the first step in exploring each content area, and that decisions are recorded in way that is meaningful to the person. Given these elements are usual components within decision-making support with people with intellectual disabilities (Stancliffe et al., Citation2020; Webb et al., Citation2020), it may be perceived as unnecessary to include them. However, such strategies are applied less consistently than is indicated (Bigby et al., Citation2020; Douglas & Bigby, Citation2020) and there is a need to be explicit.

The study made gains in demonstrating pro-active planning as a beneficial way to initiate AC planning for a population of people who have consistently been excluded from end-of-life decision making (Hunt et al., Citation2020). Although researchers are divided about the place of pro-active approaches, citing concerns that it may result in insufficiently detailed plans (McGinley & Waldrop, Citation2022; Voss et al., Citation2017), the co-researcher group reported finding it helpful to them, and felt that their plans could be revisited in future should either their health status or wishes change.

Supportive infrastructure

The outermost layer of the emergent framework, supportive infrastructure, includes four key elements: accessible information about AC planning; policy that values, promotes, and expects AC planning to occur; training and ongoing support for the guides; and, an accessible AC plan template that aligns with the standardised version, and records how decisions were made. Implementation of AC planning programmes in the general population has been shown to require systems-level infrastructure, via a governing body or funder, (Dingfield & Kayser, Citation2017; Duckworth & Thompson, Citation2017; Goodwin et al., Citation2021; Hage et al., Citation2022) to ensure that aspects such as data systems, training and ongoing support, and access to materials are adequately resourced and overseen. This may present a challenge for future implementation.

Limitations

Limitations of this study were that the sample size was small and, within the Aotearoa New Zealand context, did not include tāngata whaikaha Māori or people with significant intellectual disabilities. Small numbers of family members and health professional participants resulted in limited learning about their perspectives. Additionally, those who took part had become enthusiastic supporters of AC planning by the time that cycle 3 began, limiting what could be learnt about how to get started with AC planning for those who are unaware or wary. Additionally, the materials developed and trialled align to practices used in Aotearoa New Zealand and may have less applicability in other jurisdictions.

Implications for research and practice

This study has made significant gains in understanding how to get started with, and how to develop quality AC plans with people with intellectual disabilities, although further research is warranted. Firstly, there is a need to measure the impact that AC plans have on end-of-life outcomes and goal-concordance for people with intellectual disabilities, and to determine how frequently the completed plans should be reviewed. Secondly, there would be benefit in considering the views and needs of more diverse groups of people with intellectual disabilities; indigenous peoples such as Māori, those with complex communication needs, people who are seriously unwell or dying, as well as family members and health professionals. Furthermore, the emergent framework should be tested in other jurisdictions, particularly to ensure that tools and resources are appropriate to local requirements, and to consider how ongoing support for guides can best be provided.

Conclusion

The study achieved its objective of developing an approach to AC planning that enabled people with intellectual disabilities to get started and successfully develop their own AC plans. Not only were the AC plans considered by all co-researchers and participants to be useful and to contain clear and trusted decisions, they captured the person’s personality, values, and beliefs. The planning process led to increased confidence and comfort in talking about death and dying for people with intellectual disabilities, their relatives and guides. The resulting emergent framework illustrates the supportive infrastructure, processes, and approach to AC planning that contributed to successful outcomes. The emergent framework may have wider utility, providing a starting point for developing applicable systems of AC planning in other locations. As such, this study makes a valuable and practical contribution to the AC planning evidence base and to practice in this developing field.

Acknowledgements

The authors extend their sincere thanks to the study’s co-research group and participants, to the IHC Foundation and Health Quality and Safety Commission for funding various aspects of the study, and to the study’s advisory group members (Caroline Quick, James Skinner, Dr Kate Grundy, Sharon Brandford, and Ruth Jones).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Bekkema, N., de Veer, A., Hertogh, C. M., & Francke, A. (2014). Respecting autonomy in the end-of-life care of people with intellectual disabilities: A qualitative multiple-case study. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 58(4), 368–380. https://doi.org/10.1111/jir.12023

- Bernacki, R. E., & Block, S. D. (2014). Communication about serious illness care goals: A review and synthesis of best practices. JAMA Internal Medicine, 174(12), 1994–2003. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.5271

- Bernal, J., Hunt, K., Worth, R., Shearn, R., Jones, E., Lowe, K., & Todd, S. (2021). Expecting the unexpected: Measures, outcomes and dying trajectories for expected and unexpected death in adults with intellectual disabilities in social care settings. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 34(2), 594–605. https://doi.org/10.1111/jar.12827

- Bigby, C., Bould, E., Iacono, T., Kavanagh, S., & Beadle-Brown, J. (2020). Factors that predict good active support in services for people with intellectual disabilities: A multilevel model. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 33(3), 334–344. https://doi.org/10.1111/jar.12675

- Bigby, C, & Douglas, J. (2020). Supported Decision Making. In R.J. Stancliffe, M.L. Wehmeyer, K.A. Shogren, & B.H. Abery (Eds.), Choice, Preference, and Disability (pp. 45–66). Springer. https://cmezproxy.chmeds.ac.nz/10.1007/978-3-030-35683-5_3

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2019). Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 11(4), 589–597. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2019.1628806

- Brinkman-Stoppelenburg, A., Rietjens, J. A. C., & van der Heide, A. (2014). The effects of advance care planning on end-of-life: A systematic review. Palliative Medicine, 28(8), 1000–1025. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269216314526272

- Detering, K. M., Hancock, A. D., Reade, M. C., & Silvester, W. (2010). The impact of advance care planning on end of life care in elderly patients: Randomised controlled trial. BMJ, 340, 847–847. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.c1345

- Dingfield, L. E., & Kayser, J. B. (2017). Integrating advance care planning into practice. CHEST, 151(6), 1387–1393. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chest.2017.02.024

- Disler, R., Yuxiu, C., Luckett, T., Donesky, D., Irving, L., Currow, D. C., & Smallwood, N. (2021). Respiratory nurses have positive attitudes but lacked confidence in advance care planning for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Journal of Hospice & Palliative Nursing, 23(5), 442–454. https://doi.org/10.1097/NJH.0000000000000778

- Duckworth, S., & Thompson, A. (2017). Evaluation of the advance care planning programme. https://www.hqsc.govt.nz/assets/ACP/PR/ACP_final_evaluation_report_290317.pdf.

- Forrester-Jones, R., Beecham, J., Barnoux, M. F. L., Oliver, D. J., Couch, E., & Bates, C. (2017). People with intellectual disabilities at the end of their lives: The case for specialist care? Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 30(6), 1138–1150. https://doi.org/10.1111/jar.12412

- Goodwin, J., Shand, B., Wiseman, R., Brough, N., McGeoch, G., Hamilton, G., & Grundy, K. (2021). Achievements and challenges during the development of an advance care planning program. Australasian Journal on Ageing, 00, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajag.12945

- Grindrod, A., & Rumbold, B. (2017). Providing end-of-life care in disability community living services: An organizational capacity-building model using a public health approach. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 30(6), 1125–1137. https://doi.org/10.1111/jar.12372

- Hage, M., Nelson, E., Ginsber, J., & Potter, J. (2022). A model for standardized and proactive advance care planning. Journal of Social Work in End-of-Life & Palliative Care, 18(1), 34–45. https://doi.org/10.1080/15524256.2021.2015737

- Health Quality and Safety Commission. (2018). My advance care plan and guide. Health Quality and Safety Commission. https://www.hqsc.govt.nz/assets/ACP/PR/ACP_Plan_print_.pdf.

- Health Quality and Safety Commission. (2021). Advance care planning training manual. https://www.hqsc.govt.nz/assets/Our-work/Advance-care-planning/ACP-info-for-clinicians/Publications-resources/ACP-training-manual-2021-web-final.pdf.

- Hunt, K., Bernal, J., Worth, R., Shearn, J., Jarvis, P., Jones, E., Lowe, K., Madden, P., Barr, O., Forrester-Jones, R., Kroll, T., McCarron, M., Read, S., & Todd, S. (2020). End-of-life care in intellectual disability: A retrospective cross-sectional study. BMJ Supportive & Palliative Care, 10(4), 469–477. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjspcare-2019-001985

- McGinley, J., & Waldrop, P. (2022). Advance care planning with and for people who have intellectual and developmental disabilities. In R. J. Stancliffe, M. Wiese, P. McCallion, & M. McCarron (Eds.), End of life and people with intellectual and developmental disability: Contemporary issues, challenges, experiences and practice (pp. 124–159). Springer.

- McKenzie, N., Brandford, S., Mirfin-Veitch, B., & Conder, J. (2017). I’m still here: Exploring what matters to people with intellectual disability during advance care planning. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 30(6), 1089–1098. https://doi.org/10.1111/jar.12355

- Mertens, D. M. (2009). Transformative research and evaluation. The Guilford Press.

- Nagarajan, S. V., Lewis, V., Halcom, E., Rhee, J., Morton, R. L., Mitchel, G. K., Tieman, J., Philips, J. L., Detering, K. M., Gavin, J., & Clayton, J. (2022). Barriers and facilitators to nurse-led advance care planning and palliative care practice change in primary care: A qualitative study. Australian Journal of Primary Health, 128, 151–157. https://doi.org/10.1071/PY21081

- Noorlandt, H. W., Korfage, I., Tuffrey-Wijne, I., Festen, D., Vrijmoeth, C., van der Heide, A., & Echteld, M. (2021). Consensus on a conversation aid for shared decision making with people with intellectual disabilities in the palliative phase. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 34(6), 1538–1548. https://doi.org/10.1111/jar.12898

- Noorlandt, H. W., Korfaje, I. J., Felet, F. M. A. J., Aarts, K., Festen, D. A. M., Vrijmoeth, C., Heide, A. V. D., & Echteld, M. A. (2024). Shared decision making with frail people with intellectual disabilities in the palliative phase: A process evaluation of the In-Dialogue conversation aid in practice. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 37(1), e13158. https://doi.org/10.1111/jar.13158

- Norals, T. E., & Smith, T. J. (2015). ACP discussions: Why they should happen, why they don’t, and how we can facilitate the process. Journal of Oncology, 29(8), 567–572.

- Pino, M., Parry, R., Land, V., Faull, C., Feathers, L., & Seymour, J. (2016). Engaging terminally ill patients in end of life talk: How experienced palliative medicine doctors navigate the dilemma of promoting discussions about dying. PLoS One, 11(5), e0156174. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0156174

- Queensland Health Clinical Excellence Division. (2018). Advance care planning clinical guidelines. State of Queensland (Queensland Health). https://www.health.qld.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0037/688618/acp-guidelines.pdf.

- Rojers, J., Goldsmith, C., Sinclair, C., & Auret, K. (2019). The advance care planning nurse facilitator: Describing the role and identifying factors associated with successful implementation. Australian Journal of Primary Health, 25(6), 564–569. https://doi.org/10.1071/PY19010

- Song, M. K., Ward, S. E., Fine, J. P., Hanson, C., Feng-Chang, L., Hladik, G. A., Hamilton, J. B., & Bridgman, J. C. (2015). Advance care planning and end-of-life decision making in dialysis: A randomised control trial targeting patients and their surrogates. American Journal of Kidney Disease, 66(5), 813–822. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.ajkd.2015.05.018

- Stancliffe, R J, Shogren, K A, Wehmeyer, M L, & Abery, B H. (2020). Policies and practices to support preference, choice, and self-determination: An ecological understanding. In R.J. Stancliffe, M.L. Wehmeyer, K.A. Shogren, & B.H. Abery (Eds.), Choice, Preference, and Disability (pp. 339–334). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-35683-5_18

- Sudore, R. L., Boscardin, J., Fuez, M. A., McMahan, R. D., Katen, M. T., & Barnes, D. E. (2017). Effect of the PREPARE website vs an easy-read advance directive on advance care planning documentation and engagement among veterans. JAMA Internal Medicine, 177(8), 1102–1109. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.1607

- Swantz, M. L. (2013). Participatory action research as practice. In P. Reason, & H. Bradbury (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of action research: Participative inquiry and practice (pp. 31–48). SAGE Publications.

- Tan, A., Paterson, C., Bernacki, R., Urquhart, R., & Barwich, P. (2019). While my thinking is clear: Outcomes from a feasibility pilot of a multi-disciplinary, step-wise pathway for advance care planning in family medicine. BMJ Supportive and Palliative Care, 9(2), A10. https://doi.org/10.1136/spcare-2019-ACPICONGRESSABS.29

- Todd, S. (2013). Being there: The experiences of staff in dealing with matters of dying and death in services for people with intellectual disabilities. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 26(3), 215–230. https://doi.org/10.1111/jar.12024

- Tuffrey-Wijne, I., Giatras, N., Butler, G., Cresswell, A., Manners, P., & Bernal, J. (2013). Developing guidelines for disclosure or non-disclosure of bad news around life limiting illness and death to people with intellectual disabilities. Journal in Applied Research in Intellectual Disability, 26(3), 231–242. https://doi.org/10.1111/jar.12026

- Tuffrey-Wijne, I., Rose, T., Grant, R., & Wijne, A. (2017). Communicating about death and dying: Developing training for staff working in services for people with intellectual disabilities. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 30(6), 1099–1110. https://doi.org/10.1111/jar.12382

- United Nations. (2014). General comment number 1, Article 12: Equal recognition before the law. www.documents-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/G14/031/PDF/G1403120.pdf?OpenElement.

- Voss, H., Vogel, A., Wagemans, A., Francke, A., Metsemakers, J., Courtens, A., & de Veer, A. (2020). What is important for advance care planning in the palliative phase of people with intellectual disabilities? A multi-perspective interview study. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 33(2), 160–171. https://doi.org/10.1111/jar.12653

- Voss, H., Vogel, A., Wagemans, A., Francke, A., Metsemakers, J., Courtens, A., & Veer, A. (2019). Advance care planning in the palliative phase of people with intellectual disabilities: Analysis of medical files and interviews. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 63(10), 1262–1272. https://doi.org/10.1111/jir.12664

- Voss, H, Wagemans, A M A, Francke, A L, Metsemakers, J F M, Courtens, A M, & Veer, A J E. (2017). Advance care planning in palliative care for people with intellectual disabilities: A systematic review. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 54(6), 938–960. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2017.04.016

- Wagemans, A., Lantman, H., Proot, I., Metsemakers, J., Tuffrey-Wijne, I., & Curfs, L. (2013). End-of-life decisions for people with intellectual disabilities, an interview study with patient representatives. Palliative Medicine, 27(8), 765–771. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269216312468932

- Wagemans, A., van Schrojenstein Lantman-de Valk, H., Proot, I., Bressers, A., Metsemakers, J., Tuffrey-Wijne, I., Groot, M., & Curfs, L. (2017). Do-not-attempt-resuscitation orders for people with intellectual disabilities: Dilemas and uncertainties for ID physicians and trainees. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 61(3), 245–254. https://doi.org/10.1111/jir.12333

- Wagemans, A., van Schrojenstein Lantman-de Valk, H., Proot, I., Metsemakers, J., Tuffrey-Wijne, I., & Curfs, L. (2012). The factors affecting end-of-life decision-making by physicians of patients with intellectual disabilities in the Netherlands: A qualitative study. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 57(4), 380–389. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2788.2012.01550.x

- Watson, J., Voss, H., & Bloomer, M. J. (2019). Placing the preferences of people with profound intellectual and multiple disabilities at the center of end-of-life decision making through storytelling. Research and Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities, 44(4), 267–279. https://doi.org/10.1177/1540796919879701

- Webb, P D, Davidson, G, Edge, R, Falls, D, Keenan, F, Kelly, B, Mclaughlin, A, Montgomery, L, Mulvena, C, Norris, B, Owens, A, Irvine, Shea. (2020). Service users' experiences and views of support for decision-making. Health and Social Care in the Community. Health and Social Care in the Community, 28(4), 1282–1291. https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.12961

- Wicki, M. T. (2020). Medical end-of-life decisions for people with intellectual disabilities in Switzerland. Journal of Policy and Practice in Intellectual Disabilities, 17(3), 232–238. https://doi.org/10.1111/jppi.12340

- Wiese, M., Stancliffe, R. J., Read, S., Jeltes, G., & Clayton, J. (2015). Learning about dying, death, and end-of-life planning: Current issues informing future actions. Journal of Intellectual and Developmental Disability, 40(2), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.3109/13668250.2014.998183

- Wiese, M., Stancliffe, R. J., Wagstaff, S., Tieman, J., Jeltes, G., & Clayton, J. (2018). Talking end of life. https://www.caresearch.com.au/TEL/.