ABSTRACT

Background

Although older adults with intellectual and/or developmental disabilities face high risks of maltreatment, there are few interventions available to reduce these risks. This study describes the development of a research-based intervention that aims to reduce the risks of maltreatment for this population.

Method

The development involved close collaboration with a program advisory board (PAB). It used a three-phase approach with a cross-cultural perspective: (1) performing a needs assessment, (2) determining content and design, and (3) evaluating the usability of the intervention.

Results

The needs assessment results and input from the PAB yielded critical information that helped shape the intervention’s development. Feedback from the trainers confirmed the intervention’s usefulness and revealed suggestions for enhancing its usability.

Conclusions

The intervention developed appears to be promising for enhancing the knowledge and skills of older populations to reduce their exposure to maltreatment risks; future research should be conducted to assess its efficacy.

Interpersonal violence, victimisation, exploitation, abuse, mistreatment: the terms used to describe experiences of maltreatment vary and evolve according to the contexts and use. Results from the most recent meta-analysis report that one in six adults aged 60 or older is a victim of maltreatment (Yon et al., Citation2019). As adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities are estimated to be four to seven times at a higher risk of being victims of maltreatment than neurotypical adults (Wilson, Citation2016), the prevalence of maltreatment in older adults with intellectual and/or developmental disabilities is likely to be high; nevertheless, it is still unknown (Strasser et al., Citation2016).

On the one hand, the difficulties in establishing the prevalence and, more generally, the patterns of maltreatment in older adults with intellectual and/or developmental disabilities are partly related to the difficulty of defining “old.” Regarding the definition of age and older individuals with intellectual and/or developmental disabilities, we decided to set an age of 50 years and older as a criterion. This decision was guided by the uniqueness of the aging process in people with intellectual and/or developmental disabilities (McKenzie et al., Citation2016), which makes them more likely to experience premature aging. Therefore, the age threshold for defining older adults in this population is lower than the typical age (American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities [AAIDD], Citation2014).

On the other hand, the variability in definitions that cover the spectrum of maltreatment adds to the difficulty in establishing a clear prevalence of maltreatment (Strasser et al., Citation2016). Maltreatment includes neglecting a person’s physical and emotional needs as well as physically, emotionally, or sexually abusing another person (Hickson & Khemka, Citation2016). The National Research Council (NRC, Citation2003, p. 40) defines the maltreatment of older adults as:

(a) intentional actions that cause harm or create a serious risk of harm to a vulnerable elder by a caregiver or other person who stands in a trust relationship to the elder, or (b) failure by a caregiver to satisfy the elder’s basic needs or to protect the elder from harm.

Maltreatment of older adults with intellectual and/or developmental disabilities differs from lifetime maltreatment or maltreatment of younger adults because the types of abuse might be different as one age (e.g., financial exploitation, denial of personal rights), but also because the levels of physical and cognitive vulnerabilities are likely to be heightened (e.g., frailer health, differences in memory, stamina). With aging, the access to resources and support systems changes (e.g., moving into an institutional setting, changes in the support network, in roles), permeated by shifts in cultural attitudes and societal perceptions that may be limiting (e.g., ageism).

Recent shifts in attitudes influenced by self-advocacy movements (e.g., “nothing about us, without us,” Stack & McDonald, Citation2014) indicate that individuals with intellectual and/or developmental disabilities desire to be informed and actively involved in decisions affecting their lives, even regarding sensitive issues like abuse prevention (Hughes et al., Citation2018; Masse et al., Citation2009). Moreover, research suggests that negative side effects from abuse prevention programs are rare or non-existent with proper precautions (e.g., Egemo-Helm et al., Citation2007). Therefore, involving individuals with intellectual and/or developmental disabilities in prevention efforts is not only justifiable but increasingly recognised as essential for their empowerment and protection.

The socio-ecological model is a helpful framework that differentiates between individual, relationship, community, and societal risk factors (Araten-Bergman & Bigby, Citation2020). Societal risk factors relate to cultural attitudes, norms, expectations (e.g., ableism, ageism), socioeconomic inequalities, policies, and poor-quality health care. Community risk factors include inaccessible social services, care staff values, knowledge, and attitudes. Relationship risk factors are tied to high dependency on others, stress and burnout, socialisation to compliance, smaller networks, and high conflict. Individual risk factors include impairment characteristics, communication difficulties, low self-esteem, low self-determination, poor social and decision-making skills, limited knowledge, and social isolation (Araten-Bergman & Bigby, Citation2020). At the individual level, risk reduction addresses individual factors that increase the likelihood of maltreatment, mostly through risk assessments and implementing educational interventions to reduce victimisation risks (Fitzsimons, Citation2017). Risk reduction education aims to establish a personal “safety net.” This type of education often includes important concepts like knowledge of the law and one’s rights (such as the right to refuse), as well as understanding proper terminology for body parts (particularly about sexual abuse) (Fitzsimons, Citation2017; Hollomotz, Citation2009).

In the available intervention research for adults with intellectual disabilities, the Effective Strategy-based Curriculum for Abuse Prevention and Empowerment – for adults with Developmental Disabilities (ESCAPE-DD) stands out for its efficacy and multiple uses in different countries (e.g., Hickson et al., Citation2015). Designed specifically for adults with intellectual and/or developmental disabilities, ESCAPE-DD extensively focuses on building independent and effective decision making in social situations from a prevention standpoint. ESCAPE-DD, and its later version (ESCAPE-NOW) are widely used, not only in the United States but also in Europe (see Khemka & Hickson, Citation2021 for a thorough description of ESCAPE-DD and updated version ESCAPE-NOW). For example, ESCAPE-DD has been successfully translated and implemented in the French-speaking part of Switzerland (Noir & Petitpierre, Citation2012; Petitpierre et al., Citation2016). Nevertheless, although continuing to provide a robust approach to risk reduction training, the curriculum does not address issues and risk factors relevant to older adults with intellectual and/or developmental disabilities.

The purpose of this study is to address the lack of maltreatment prevention programs – more precisely, the lack of risk reduction interventions focused at an individual level of prevention – designed for older adults with intellectual and/or developmental disabilities. This population is at a heightened risk of victimisation and faces unique challenges that require tailored prevention curricula to mitigate the risk of abuse. Nevertheless, research on this topic is scarce: maltreatment experiences of older adults with intellectual and/or developmental disabilities are poorly documented, and no interventions have been designed yet for this population (Beaulieu et al., Citation2022). The study thus aims to answer the following research question: How can ESCAPE be adapted to address the specific risk factors and challenges faced by older adults with intellectual and/or developmental disabilities?

To answer this research question, we adopted a cross-cultural approach, engaging with practitioners and researchers in the field of intellectual and/or developmental disabilities and elder maltreatment in the United States and Switzerland. This approach consisted of three specific phases that address specific objectives. The first phase, the needs assessment, focused on identifying the specific risk factors and challenges faced by older adults with intellectual and/or developmental disabilities concerning maltreatment experiences. The second phase focused on the development of the curriculum itself in terms of content and design, while the last phase consisted of a field test, where we assessed the usability of the curriculum.

Method

Adopting a cross-cultural development approach (simultaneously in the United States and in the French-speaking part of Switzerland) generates important insights and broadens perspectives; it also ensures that the new intervention is appropriate across all participating cultures and contexts (Vivat et al., Citation2013).

The development of ESCAPE-E was informed, on the one hand, by the approach proposed by Schneiderhan et al. (Citation2019) on educational curriculum development, and the other, by Hockley et al. (Citation2019) framework for cross-cultural development and implementation of interventions. Accordingly, the development of ESCAPE-E included the following phases: (1) performing a needs assessment, (2) determining content and design, (3) implementing and evaluating the usability of the risk reduction intervention (see Appendix for an overview of the methods used in the three phases). Further, all aspects of development (e.g., recruitment, informed consent by participants, protocols for participating in training), including validation of intervention content and scripts for training, followed full ethical guidelines at the two participating agencies and Institutional Review Board (IRB) requirements at the first two authors’ primary institutions.

Phase 1: Needs assessment

We organised two online focus groups and one online survey to reply to the first part of our research questions. The focus groups aimed to gather suggestions from current ESCAPE trainers on the components necessary to adapt ESCAPE to meet the needs of older adults with intellectual and/or developmental disabilities. The online survey’s purpose was to gather views on the maltreatment of older adults with intellectual and/or developmental disabilities and its prevention.

Focus groups

Recruitment

For the focus groups, we partnered with the two Swiss agencies using the French translation of ESCAPE-DD. We asked if the ESCAPE trainers would be willing to meet for a 1-hour online meeting.

Participants

All current ESCAPE trainers in Switzerland (N = 6, i.e., three in each agency) agreed to meet. The six trainers (five women and one man, all Caucasian, all Swiss) were social educators with around ten years of experience working with people with intellectual disabilities.

Procedure

The two focus groups were conducted online (i.e., one meeting per agency) and followed the same structured interview guide.

Online survey

Recruitment

The survey was promoted through relevant online platforms and agencies for adults with intellectual and/or developmental disabilities in the United States and Switzerland. Additionally, e-mails advertising the survey were sent to specific agencies or people that we know are making use of ESCAPE or active in the field of elder abuse or/and abuse of people with intellectual and/or developmental disabilities.

Participants

Eighty-six practitioners and researchers in the field of intellectual and/or developmental disabilities and elder maltreatment in the United States and Switzerland completed the survey (see ).

Table 1. Online survey: demographic information on survey respondents.

Procedure

The survey was conducted during the winter of 2021–2022 and comprised 28 questions, of which two were relevant to this study. Participants were asked to provide input on designing a risk reduction intervention for older adults with intellectual and/or developmental disabilities. They were also asked to describe situations where they witnessed or became aware of maltreatment of older adults with intellectual and/or developmental disabilities.

Phase 2: Content and design

Cross-cultural perspective and supports

The content and design were determined in collaboration with an eight-member international Program Advisory Board (PAB). We aimed for a PAB composed of six to eight members, with about half of them from the United States and the other half from the French-speaking part of Switzerland. To enable the full participation of all PAB members, we decided to structure the PAB into two groups, one where meetings would be held in English and the others in French. We recruited four members through their participation in the online survey, where they had inserted their e-mail addresses to signify that they would be interested in joining such a board. We chose them because they had extensive clinical experience with (older) adults with intellectual and/or developmental disabilities (i.e., more than ten years) and had prior knowledge (or understanding) of ESCAPE-DD/NOW. We further recruited three other persons to balance the PAB members’ professions and regions where they lived – those three persons also had extensive clinical experience with (older) adults with intellectual and/or developmental disabilities and had prior knowledge of ESCAPE-DD/NOW. Four members came from the French-speaking part of Switzerland (self-advocate, social educator, psychiatrist, researcher); three members came from the United States (psychologist, directors of agencies serving adults with intellectual and/or developmental disabilities); and one member was from Sweden (researcher).

Nine one-hour online meetings were held with the PAB (five in French, four in English). During the meetings with the PAB, we requested feedback regarding the curriculum’s content (objectives, topics) and design (accessibility, delivery). During the 7-month iterative development process, the PAB provided input that helped ensure that the curriculum met the needs of older adults with intellectual and/or developmental disabilities, and refinement to the curriculum content was made on an ongoing basis to reflect their inputs.

To ensure full participation by the self-advocate on the PAB, one member of the research team met them online a few days before each PAB meeting to review materials together and clarify any questions. The process of developing curriculum and meeting materials in two languages was well planned, with English serving as the source language and translations done in French. Although most of the translation corresponded with the original text words, there were a few instances when the word form had to be changed while keeping the original meaning. For this, the translation and the choice of words was informed by the previous work conducted to create a French version of ESCAPE-DD (Petitpierre et al., Citation2016) and feedback of the French-speaking PAB members.

Phase 3. Usability test

In phase 3, we conducted a usability test of the curriculum. Usability refers to “the extent to which an intervention can be used by specified users to achieve specified goals with effectiveness, efficiency, and satisfaction” (Lyon & Bruns, Citation2019, p. 1). Usability refers to the characteristics of the intervention itself and is one of the most critical determinants of both perceptual (e.g., appropriateness, feasibility) and behavioural (e.g., fidelity) implementation success (Lyon & Bruns, Citation2019). Testing the usability of a new intervention is thus an important step that contributes to completing its development before conducting a large-scale efficacy study.

Recruitment

We partnered with two agencies, one in the US and one in Switzerland, that provide services to adults with intellectual and/or developmental disabilities to conduct a usability test of ESCAPE-E. Both agencies were represented on the PAB. One of the agency directors represented in the PAB, located in New York City, selected one staff member who was a supervising licensed psychologist to implement ESCAPE-E for the usability test. The social educator from the Swiss agency, located close to Sion (Wallis, French-speaking part), received approval from their director and agreed to implement the French version of ESCAPE-E. The social educator from the Swiss agency participated in the focus group and was familiar with ESCAPE-DD, while the US trainer wasn’t. Both trainers had extensive experience providing direct instruction services and support to (older) adults with intellectual and/or developmental disabilities.

A member of the research team conducted three one-hour online training sessions with each trainer. During these meetings, the procedures and materials for two lessons, including aims, scripts, activities, and stickers, were reviewed and discussed. Trainers were given the chance to ask questions and further discuss the information presented.

Participants

The two designated ESCAPE-E trainers each recruited five participants within their agencies, meeting the following inclusion criteria: having intellectual and/or developmental disabilities, being 50 years or over in age, and being able to verbally participate in a small group conversation in English (for US participants) or French (for Swiss participants). No further inclusion/exclusion criteria were specified. They gave and/or read with the prospective participants a short one-page consent form, written in an easy-to-read and understandable format, with the intervention described. They were asked if they wished to participate. Ten participants (i.e., five at each agency) gave their informed consent and agreed to participate.

Procedure

Implementation took place during Spring 2022 at the two agency sites, one in New York City and one in the French-speaking part of Switzerland, close to Sion (Wallis). Of the ten individuals who consented to participate across both sites, nine attended the six lessons of ESCAPE-E (six men, among them four French-speaking, and three women, among them one French-speaking). One participant attended the first lesson and afterward decided not to attend anymore.

Participants met with the trainer in a quiet room at their day program site for the six intervention sessions. Intervention sessions were scheduled on a weekly or bi-weekly basis whenever possible. If a participant was absent for one session, they were given an individual make-up session before their next training session.

After each lesson, trainers completed an online feedback form. The form comprised four sections: (1) general information (e.g., date, numbers of participants, duration of the lesson); (2) implementation checklist (seven items to rate on a five-point scale from never to always, e.g., I read the exact wording of the script to the participants; I reinforced correct responses); (3) lesson rating (five items to rate on a five-point scale from strongly disagree to strongly agree; e.g., the trainer instructions were clear and easy to implement, this lesson is useful and effective for older adults with intellectual and/or developmental disabilities), (4) lesson feedback (three open-ended questions; e.g., what did you find particularly helpful/relevant in this lesson?).

Each trainer administered a brief feedback form comprising four questions at the end of the six lessons to record each participant’s impressions on the usability and usefulness of the curriculum in their lives. The first and last question used a three-point Likert scale with supporting face images for options Yes, I don’t know, No.

Results

Phase 1: Needs assessment results

Focus groups results

The key recommendations that emerged from the focus groups meetings were taken into consideration during the initial design of the new intervention. They included the need to adapt the content to integrate the concept of neglect that is highly prevalent in the lives of older adults with intellectual and/or developmental disabilities; adjust the mode of delivery (i.e., constitute smaller groups – three to five people); use accessible language (i.e., follow the easy-to-read and understand format, Inclusion Europe, Citation2009).

Online survey results

The global survey results are detailed elsewhere (Khemka et al., Citationin preparation). Two open-ended survey questions yielded significant findings for this study; their results were analysed through a thematic content analysis following the procedure detailed by Paillé and Mucchielli (Citation2021) (see ).

Respondents were asked to provide considerations for designing a risk reduction intervention for older adults with intellectual and/or developmental disabilities. Twenty-four recommendations were made, focusing on individual-level factors such as addressing specific scenarios common among older adults, including financial exploitation and inadequate medical care, as well as enhancing self-awareness within relationships and understanding different forms of abuse, particularly financial exploitation and neglect from family, friends, and staff. These recommendations closely aligned with those from the focus groups and served as a solid foundation for the subsequent steps in the development of the curriculum (content, design).

Respondents were also asked to describe situations where they witnessed or became aware of maltreatment of older adults with intellectual and/or developmental disabilities. Forty-five respondents provided a total of 64 examples. The descriptions of maltreatment situations of older adults with intellectual and/or developmental disabilities in French (Switzerland context) were largely similar to those in English (US context). Relatively more situations were recalled for types of maltreatment commonly experienced by older adults, such as financial exploitation and neglect (social exclusion, medical care). Examples included instances where an individual’s niece took control of their financial benefits, limiting their access to money and living standards, or witnessing an aide pushing an older adult aggressively in their wheelchair. While no examples of sexual abuse were reported in French, examples such as an aide refusing to provide transportation unless sexual acts were performed were reported as instances of maltreatment in English.

Table 2. Online survey results.

Phase 2: Content and design results

Vignette development

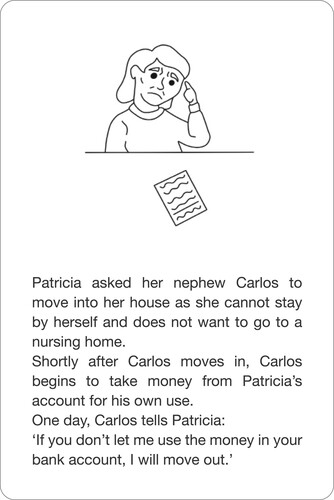

A key instructional feature of ESCAPE-DD/NOW is the use of illustrated vignettes designed to depict in training real-life scenarios involving a protagonist and a perpetrator(s). The vignettes for ESCAPE-E were selected from three main sources: (1) the 64 example situations from the needs assessment survey, (2) the existing 42 vignettes from ESCAPE-NOW, and (3) a literature review on research studies describing vignettes of maltreatment of older adults. Drawing from all the above sources, the research team created an initial set of 49 vignettes (8 vignettes for each abuse or maltreatment type), following a list of pre-defined rules (e.g., maximum of four sentences; present tense; every character introduced has a name). Three PAB members then rated the 49 vignettes for their level of importance (very important: definitely include in the curriculum; important: maybe include in the curriculum; not important: do not include in the curriculum). Fourteen vignettes were excluded because one or more members rated them as “not important,” whereas 22 vignettes were kept, as they were unanimously rated as very important/important. Six additional vignettes were selected from those rated as very important or important to balance for type of situation. In total, 28 vignettes were finalised for ESCAPE-E, with minimum of four vignettes per maltreatment type with a balance for gender, settings (e.g., home, workplace, community), and interpersonal situations (e.g., caregiver, family, friends) depicted. Each vignette comprised a short description of an interpersonal decision-making situation featuring a protagonist as the decision faced with a maltreatment incident (verbal, sexual, or physical abuse; or financial exploitation, social exclusion, or neglect). Additionally, six vignettes depicting non-abusive (positive) interpersonal situations were adapted from existing non-abusive vignettes in ESCAPE-NOW to bring them closer to the focus of the curriculum on older adults. All vignettes were newly illustrated with black and white graphic images (see ).

Instructional content and design

The curriculum structure was grounded in a decision-making framework already used in other ESCAPE and adjusted to reflect recent theoretical advances in the understanding of interpersonal decision making in individuals with intellectual and/or developmental disabilities (see Khemka & Hickson, Citation2021, for a detailed explanation of pathways of decision processing). The content was also informed by and built upon the results of the online survey; literature review; and PAB discussions. Additionally, the content was carefully chosen to provide an increased understanding and awareness of the dynamics (and power imbalances) between caregivers and older adults with intellectual and/or developmental disabilities that can lead to maltreatment (e.g., caregiver work overload, financial strain, victim-perpetrator relationship, Ernst, Citation2019; Pillemer et al., Citation2016). The vignettes canvassed varying interdependence of family/caregiver roles and functions and emotional complexity commonly seen in relationships with older adults. This way, participants can recognise feelings associated with healthy and abusive supported relationships (emotional component) and learn how to address maltreatment using a 4-step decision-making strategy within a supported relationship (cognition component). For example, a broad range of supported relationships are covered in the vignette (e.g., driving to doctor appointments, arranging meals, providing personal care, assisting with money management, assisting with medications). Finally, because it is essential to believe in one’s ability to change a problem situation to take action on a decision (motivation component), all lessons are framed in an empowering way, aiming to enhance personal agency beliefs.

The curriculum design and activities were chosen to maximise accessibility to a wide range of intellectual and adaptive functioning. It follows a user-oriented design similar to that described by Vereenooghe and Westermann (Citation2019), for example, by using easy-to-read language, large font size, images to illustrate concepts, and a clear structure, with the same design for each topic. The review activities in the curriculum are based on sorting tasks specific to revising the content of each lesson. By allowing for repetition and checks for understanding/recall, these activities are likely to be appropriate to address the learning needs of a broad range of older adults with intellectual and/or developmental disabilities, including those with dementia (Regier et al., Citation2017).

Proposed intervention outline

The initial proposed ESCAPE-E comprised six lessons that aimed to last 45 min (pro lesson) and to be delivered in small groups (3–5 older adults with intellectual and/or developmental disabilities per trainer). In each lesson, the trainer used a script, based on an explicit instructional model (app. 15 pages per lesson), and several activity sheets (either printed or displayed via a PowerPoint); the participants received individual binders with one to five activity sheets to complete per lesson, by including stickers for response choices.

The first two lessons trained participants to recognise verbal, physical, and sexual abuse and other forms of maltreatment commonly experienced by older adults with intellectual and/or developmental disabilities such as financial exploitation, social exclusion, and neglect in interpersonal situations. The next two lessons focused on identifying emotions related to positive and negative relationships and applying emotional coping strategies in case of distress. The last two lessons trained participants to follow a 4-step decision-making strategy to make self-protective decisions (i.e., with the key goals to be safe now and stay safe later) in interpersonal situations guided by four key questions: (1) Is there a problem in the situation? (2) What are the possible choices? (3) Would the choice meet the two safety goals (safe now, safe later)? (4) Decide how to act upon the selected choice: What can (protagonist’s name) do to stop the problem right away and what can (protagonist’s name) do to make sure that the problem does not happen again? The decision-making strategy instruction allowed the participants to learn and practice, through role play, skills that might help them to prevent maltreatment from happening (linked to the goal of being safe now) right away and/or reporting to others (linked to the goal of being safe later) for support and prevention.

Phase 3: Usability test results

Usability test: Trainers’ feedback

Trainers took, on average, eleven minutes to complete the usability feedback form. Globally, the curriculum was implemented as intended, with an average mean of implementation fidelity ranging from 3.7 to 5. The least well-adhered to fidelity criterion in each lesson for both trainers was I read the exact wording of the script to the participants. The trainers reported that repeating short phrases and doing frequent informal probes to check for participants’ understanding by paraphrasing was helpful, suggesting that some flexibility from reading the script verbatim might be necessary to individualise the pace and keep participants engaged in a lesson. The trainer’s instructions were mostly rated as clear and easy to implement, and the trainers perceived the level of instruction for older adults with intellectual and/or developmental disabilities as appropriate. Lesson 4, centred on empowerment and coping, was perceived as least relevant and efficient for the French-speaking group. The feedback from the two trainers on the open-ended questions was very similar. For example, both trainers considered the vignette images as helpful and reported that participants enjoyed the illustrations and the activities – especially using stickers to complete their sheets. Each lesson lasted about fifteen minutes more than the 45 min initially planned, and not all tasks could be completed within the allotted time, necessitating another look for how the content could be evenly distributed across the lessons.

Usability test: Participants’ feedback

To the question (1) “Has this training been helpful?” all participants replied yes; three drew attention to the vignettes when asked, “What parts of the training were helpful?” (“story”; “picture”; “pictures”), three other participants found it helpful to “know how to say stop” or protect themselves; one participant referred to the stickers, and two participants did not fill in this part of the question/did not know. Regarding the second question (“What are some important things you need to think about when you have to make a decision?”), four participants replied, “(stay) safe now, safe later” while the other four participants’ responses related to asking for help when needed, talking to someone, and thinking about possible choices. One participant did not fill in this question. (3) Regarding the third question, do you “have suggestions for how to improve this training?”, most (7) replied that they liked it how it was. One participant wrote “need more people,” which prompted another participant to write “will my [more] people.” (4) Except for one participant who did not know, all indicated that they would recommend this training to someone else when asked: “Would you recommend this training to someone else?”

Adaptations performed to enhance the usability

We used the results of the usability assessment to perform minor and substantial adaptations to enhance the usability of ESCAPE-E: the curriculum was structured differently to spread out the content more evenly across lessons (i.e., the curriculum was divided into eight lessons instead of six lessons with a final Wrap Up session; the review activities were shortened); the instructor’s manual was enhanced to improve clarity about how trainers can adapt the curriculum with different groups based on time and participants needs (e.g., additional information on accommodation were provided, with recommendation like, the lesson should not last more than one hour with a break – ideally 30–45 min sessions; group of three to five participants, depending on the group, a co-trainer can be helpful to support participants); and the content of Lesson 4 in French was reviewed to better convey the notions of empowerment and coping (i.e., after discussion with the French-speaking members of the PAB, the activities on empowerment and coping were revised around the topic of “what helps me” and script was reviewed to be easier to understand). A follow-up discussion was conducted with each trainer to present the adaptations made to the intervention. provides an overview of ESCAPE-E, revised.

Table 3. Overview of ESCAPE-E.

Discussion

In this study, we described how we developed, within a three phases approach, a research-based intervention that aims to reduce the risks of maltreatment of older adults with intellectual and/or developmental disabilities. While the framework of the curriculum is grounded in research on decision-making and past intervention efforts (see Khemka & Hickson, Citation2021), its development was guided by the results of a needs assessment and feedback from an international PAB.

The three phases of our approach, namely the needs assessment, determination of content and objectives, and usability testing, were conducted with a cross-cultural lens. This perspective was made possible by the collaboration of our research team comprising members from the United States and Switzerland, as well as the valuable input received during the PAB meetings. During the first phase, we sought to determine whether the curriculum needed to be adapted differently for the English and French versions. The results of the needs assessment and extensive discussions with PAB members led us to the decision of developing two similar curricula that were culturally appropriate for the respective American and Swiss contexts.

The usability assessment highlighted common and specific challenges in each field test – challenges that we addressed through minor and substantial adaptations to ESCAPE-E. The main difference between the curriculum's English and French versions lies in the lesson centred around empowerment and coping – two words that do not have an exact equivalent in French (Knafo et al., Citation2015; Lipietz, Citation2017). The usability assessment shed light on the translation issue surrounding these concepts, which led us to modify the content and activities to better convey their meaning and reduce the complexity resulting from a literal translation. In the French version, we used the terms “usefulness” and “helpfulness” to convey the notions of enhancing autonomy, decision-making abilities, and coping with specific situations, as opposed to the terms “empowerment” and “coping.”

The main strength of our proposed intervention lies in its focus on addressing the critical issue of reducing maltreatment risks in older adults with intellectual and/or developmental disabilities, an area that has received limited attention in research and intervention efforts to date (Beaulieu et al., Citation2022). Nevertheless, this study has several limitations. Although the development process incorporated the invaluable input of one self-advocate and integrated his feedback into the final materials, the intervention developed remained a research-based intervention and did not use a participative approach. Further research is necessary to ensure sustained involvement and input from older adults with intellectual and/or developmental disabilities. For example, future research could involve these individuals as co-researchers during the planning of an efficacy intervention, serve as co-trainers to help deliver the intervention or utilise continuous feedback mechanisms such as regular focus groups to gather their insights consistently. This continued engagement will help shape future directions in prevention efforts, ensuring that interventions are driven by a comprehensive understanding of the unique needs and perspectives of this population. Additionally, it is important to note that while ESCAPE-E primarily focuses on individual-level risk reduction as an educational intervention for preventing maltreatment, addressing elder maltreatment necessitates a comprehensive approach that encompasses structural and societal interventions.

Conclusion

In conclusion, using a three-phase approach with a cross-cultural lens can be an effective strategy for developing interventions that are relevant in different countries and languages to reduce maltreatment risks in older adults with intellectual and/or developmental disabilities. Moving forward, the next phase of this research involves conducting a large-scale intervention study to assess the curriculum’s efficacy in reducing the risks of maltreatment of older adults with intellectual and/or developmental disabilities. This could be done by measuring pre- and post-intervention rates of reported incidents and perceptions of maltreatment among participants, utilising both quantitative surveys and qualitative interviews to capture a comprehensive view of the intervention’s impact. This study will provide valuable insights into the curriculum’s efficacy, further advancing our understanding of reducing the risks of maltreatment in older adults with intellectual and/or developmental disabilities. Finally, while we used a cross-cultural approach, our study is part of a research stream that has been conducted only within a Western context (Arnett, Citation2008). Future studies focusing on the maltreatment of older adults with intellectual and/or developmental disabilities should critically assess varied cultural contexts and examine potential socio-cultural dynamics. This could include, for example, beyond the examination of elder maltreatment differences between the United States and Europe, an analysis of differences between urban and rural settings and the role of physical and social isolation in the maltreatment of older adults (with and without intellectual and/or developmental disabilities) (Henderson et al., Citation2021). This nuanced approach will better equip service providers to address the unique challenges faced by older adults with intellectual and/or developmental disabilities, fostering more effective and comprehensive strategies for maltreatment prevention.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to everyone who participated in the development and evaluation of the ESCAPE-E curriculum, with special thanks to Dr. Sarah Hatcher and Sofia de Sousa, who assisted with the field testing. We would also like to thank the Program Advisory Board members for their time and valuable inputs (presented in alphabetical order): Dr. Patrik Arvidsson, Dr. Mary Donahue-Maxham, Tracy Higgins, Dr. Markus Kosel, Dr. Geneviève Petitpierre, Connie Senior, Sofia de Sousa, & Pierre Weber. We thank Alexandra Overton for all the illustrations in the curriculum.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities. (2014). Position statement on aging. https://www.aaidd.org/news-policy/policy/position-statements/aging

- Araten-Bergman, T, & Bigby, C. (2020). Violence Prevention Strategies for People with IntellectualDisabilities: A Scoping Review. Australian Social Work, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/0312407X.2020.1777315

- Arnett, J. J. (2008). The neglected 95%: Why American psychology needs to become less American. American Psychologist, 63(7), 602–614. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.63.7.602

- Beaulieu, M., Carbonneau, H., Rondeau-Leclaire, A., avec la collaboration de Marcoux, L., Hébert, M., & Crevier, M. (2022). Maltraitance psychologique et maltraitance matérielle et financière envers les personnes ai^nées ayant des incapacités. Sommaire exécutif d’un rapport de recherche partenariale entre la Chaire de recherche sur la maltraitance envers les personnes ai^nées et le CIUSSS de l’Estrie-CHUS remis à l’OPHQ. Sherbrooke.

- Burnett, J, Suchting, R, Green, C E, Cannell, M B, & Dyer, C B. (2020). Socioecological indicatorsof senior financial exploitation: An application of data science to 8,800 substantiated mistreatment cases. Journal of Elder Abuse and Neglect, 32(2), 105–120. https://doi.org/10.1080/08946566.2020.1737615

- Codina, M., Pereda, N., & Guilera, G. (2022). Lifetime victimization and poly-victimization in a sample of adults with intellectual disabilities. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 37(5), 2062–2082. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260520936372

- Egemo-Helm, K. R., Miltenberger, R. G., Knudson, P., Finstrom, N., Jostad, C., & Johnson, B. (2007). An evaluation of in situ training to teach sexual abuse prevention skills to women with mental retardation. Behavioral Interventions, 22(2), 99–119. https://doi.org/10.1002/bin.234

- Ernst, J. (2019). Older adults neglected by their caregivers: Vulnerabilities and risks identified in an adult protective services sample. The Journal of Adult Protection, 21(1), 5–15. https://doi.org/10.1108/JAP-07-2018-0014

- Fitzsimons, N. M. (2017). Partnering with people with disabilities to prevent interpersonal violence: Organization practices grounded in the social model of disability and spectrum of prevention. In A. Johnson, J. Nelson, & E. Lund (Eds.), Religion, disability, and interpersonal violence (pp. 45–65). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-56901-7_4

- Henderson, C. R., Caccamise, P., Soares, J. J. F., Stankunas, M., & Lindert, J. (2021). Elder maltreatment in Europe and the United States: A transnational analysis of prevalence rates and regional factors. Journal of Elder Abuse & Neglect, 33(4), 249–269. https://doi.org/10.1080/08946566.2021.1954573

- Hickson, L., & Khemka, I. (2016). Prevention of maltreatment of adults with INTELLECTUAL AND/OR DEVELOPMENTAL DISABILITIES: Current status and new directions. In J. R. Lutzker, K. Guastaferro, & M. B. Benka-Coker (Eds.), Maltreatment of people with intellectual and developmental disabilities (pp. 233–262). American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities.

- Hickson, L., Khemka, I., Golden, H., & Chatzistyli, A. (2015). Randomized controlled trial to evaluate an abuse prevention curriculum for women and men with intellectual and developmental disabilities. American Journal on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 120(6), 490–503. https://doi.org/10.1352/1944-7558-120.6.490

- Hockley, J., Froggatt, K., Van den Block, L., Onwuteaka-Philipsen, B., Kylänen, M., Szczerbińska, K., Gambassi, G., Pautex, S., Payne, S. A., & PACE. (2019). A framework for cross-cultural development and implementation of complex interventions to improve palliative care in nursing homes: The PACE steps to success programme. BMC Health Services Research, 19(1), 745. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-019-4587-y

- Hollomotz, A. (2009). Beyond ‘vulnerability’: An ecological model approach to conceptualizing risk of sexual violence against people with learning difficulties. British Journal of Social Work, 39(1), 99–112. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcm091

- Hughes, R. B., Robinson-Whelen, S., Goe, R., Schwartz, M., Cesal, L., Garner, K. B., Arnold, K., Hunt, T., & McDonald, K. E. (2018). “I really want people to use our work to be safe” … using participatory research to develop a safety intervention for adults with intellectual disability. Journal of Intellectual Disabilities, 24(3), 309–325. https://doi.org/10.1177/1744629518793466

- Inclusion Europe. (2009). L’information pour tous, règles européennes pour une information facile à lire et à comprendre. http://www.unapei.org/IMG/pdf/Guide_ReglesFacileAlire.pdf

- Khemka, I., & Hickson, L. (Eds.). (2021). Decision making by individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Positive Psychology and Disability Series. Springer.

- Khemka, I., Hickson, L., & Tabin, M. (in preparation). Overview of elder abuse patterns.

- Knafo, A., Guilé, J. M., Breton, J. J., Labelle, R., Belloncle, V., Bodeau, N., Boudailliez, B., De La Rivière, S. G., Kharij, B., Mille, C., Mirkovic, B., Pripis, C., Renaud, J., Vervel, C., Cohen, D., & Gérardin, P. (2015). Coping strategies associated with suicidal behaviour in adolescent inpatients with borderline personality disorder. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 60, 46–54.

- Lipietz, A. (2017). L’empowerment, une pratique émancipatrice, by Marie-Hélène Bacqué, and Carole Biewener. Rethinking Marxism, 29(3), 499–503. https://doi.org/10.1080/08935696.2017.1385323

- Lyon, A. R., & Bruns, E. J. (2019). From evidence to impact: Joining our best school mental health practices with our best implementation strategies. School Mental Health, 11(1), 106–114. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12310-018-09306-w

- Masse, M., Petitpierre, G., Jossevel, J. D., & Vidon, C. (2009). Prévention de la maltraitance en institution: collaboration autour de l’élaboration d’un support pédagogique [Prevention of abuse in institutions: Collaboration on the development of an educational support material]. In V. Guerdan, G. Petitpierre, J. P. Moulin, & M. C. Haelewyck (Eds.), Participation et responsabilités sociales: un nouveau paradigme pour l’inclusion des personnes avec une déficience intellectuelle [Participation and social responsibilities: A new paradigm for the inclusion of persons with intellectual disabilities] (pp. 660–669). Peter Lang.

- McKenzie, K., Martin, L., & Ouellette-Kuntz, H. (2016). Frailty and intellectual and developmental disabilities: A scoping review. Canadian Geriatrics Journal, 19(3), 103–112. https://doi.org/10.5770/cgj.19.225

- National Center on Elder Abuse. (n.d.). Types of elder mistreatment. https://ncea.acl.gov/What-We-Do/Research/Statistics-and-Data.aspx#types

- National Research Council. (2003). Panel to review risk and prevalence of elder abuse and neglect. National Academies Press.

- Noir, S., & Petitpierre, G. (2012). La prévention de la maltraitance envers les personnes avec une déficience intellectuelle: présentation du programme ESCAPE-DD. Revue suisse de pédagogie spécialisée, 3, 17–21. https://edudoc.ch/record/105536?ln=fr

- Paillé, P., & Mucchielli, A. (2021). L’analyse qualitative en sciences humaines et sociales. Armand Colin.

- Petitpierre, G., Borloz, M., Fellay, F., & Léonard, E. (2016). ESCAPE-DD en Facile à Lire et à comprendre. Un programme d’apprentissage de stratégies de prévention des abus et de développement de l’empowerment destiné à des adultes ayant une déficience intellectuelle. Traduction française autorisée [Unpublished manuscript]. University of Fribourg.

- Pillemer, K., Burnes, D., Riffin, C., & Lachs, M. S. (2016). Elder abuse: Global situation, risk factors, and prevention strategies. The Gerontologist, 56(Suppl 2), S194–S205. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnw004

- Regier, N., Hodgson, N., & Faan, L. (2017). Characteristics of activities for persons with dementia at the mild, moderate, and severe stages. The Gerontologist, 57(5), 987–997. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnw133

- Schneiderhan, J., Guetterman, T. C., & Dobson, M. L. (2019). Curriculum development: A how to primer. Family Medicine and Community Health, 7(2), e000046. https://doi.org/10.1136/fmch-2018-000046

- Stack, E., & McDonald, K. E. (2014). Nothing about us without us: Does action research in developmental disabilities research measure up? Journal of Policy and Practice in Intellectual Disabilities, 11(2), 83–91. https://doi.org/10.1111/jppi.12074

- Strasser, S. M., Smith, M. O., & O’Quin, K. (2016). Prevention of maltreatment of adults with INTELLECTUAL AND/OR DEVELOPMENTAL DISABILITIES: Current status and new directions. In J. R. Lutzker, K. Guastaferro, & M. B. Benka-Coker (Eds.), Maltreatment of people with intellectual and developmental disabilities (pp. 233–262). American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities.

- Vereenooghe, L., & Westermann, C. (2019). Co-development of an interactive digital intervention to promote the well-being of people with intellectual disabilities. International Journal of Developmental Disabilities, 65(3), 128–134. https://doi.org/10.1080/20473869.2019.1599606

- Vivat, B., Young, T., Efficace, F., Sigurđadóttir, V., Arraras, J. I., Åsgeirsdóttir, G. H., Brédart, A., Costantini, A., Kobayashi, K., Singer, S., & on behalf of the EORTC Quality of Life Group, X. (2013). Cross-cultural development of the EORTC QLQ-SWB36: A stand-alone measure of spiritual wellbeing for palliative care patients with cancer. Palliative Medicine, 27(5), 457–469. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269216312451950

- Wilson, C. (2016). Victimisation and social vulnerability of adults with intellectual disability: Revisiting Wilson and Brewer (1992) and responding to updated research. Australian Psychologist, 51(1), 73–75. https://doi.org/10.1111/ap.12202

- Yon, Y., Mikton, C. R., Gassoumis, Z. D., & Wilber, K. H. (2017). Elder abuse prevalence in community settings: A systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet Global Health, 5(2), e147–e156. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(17)30006-2

- Yon, Y., Ramiro-Gonzalez, M., Mikton, C. R., Huber, M., & Sethi, D. (2019). The prevalence of elder abuse in institutional settings: A systematic review and meta-analysis. European Journal of Public Health, 29(1), 58–67. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/cky093

Appendix

Overview of the methods used in the three phases of curriculum development