Abstract

Cancer control in Canada refers to the development of comprehensive programs utilising modern techniques, tools and approaches that actively prevent, cure or manage cancer. The scope of such programs is quite vast. They range from prevention, early detection and screening, comprehensive treatment both curative and palliative to comprehensive palliative care. Cancer is a disease associated with the aging population, and as the population ages the incidence of cancer would be expected to rise as well. This in itself poses a great challenge. In addition, the aging population demographics with the projected rise in the numbers of senior citizens, especially the over 80 group in the next decade, poses its own creative challenges to health planners. In Canada, health care is centrally administered, and controlled by the provincial governments of Canada, under the Canada Health Act. The challenge of developing comprehensive programs for the geriatric population requires changes in the care models and care pathways. The patient-centred models that have been adapted require a multidisciplinary approach to the clientele and their families that integrates cancer therapy and geriatric care and realities. This requires changes in the nursing and medical approach, as well as education in the subtleties of the two intersecting medical realities.

Introduction

Cancer control in Canada refers to the development of comprehensive programs utilising modern techniques, tools and approaches that actively prevent, cure or manage cancer [Citation1]. The scope of such programs is quite vast. They range from prevention, early detection and screening, comprehensive treatment both curative and palliative to comprehensive palliative care. It also involves monitoring and analysis of trends in disease incidence, of cost benefits, resource needs and outcome results of trends at each step of the programs. It also requires adaptability and program modification, often a change of direction or introduction of new principles, approaches and treatment objectives.

Cancer is a disease associated with the aging population, and as the population ages the incidence of cancer would be expected to rise as well [Citation2]. This in itself poses a great challenge due to the complexity and scope of the geriatric population from the active and healthy to the vulnerable. In addition, the aging population demographics with the projected rise in the numbers of senior citizens, especially the over 80 group poses its own creative challenges to health planners [Citation3].

In Canada, health care is centrally administered, and controlled by the provincial governments of Canada, under the Canada Health Act [Citation3]. In Canada, with few exceptions the provision of cancer services is a provincial responsibility, and most cancer control programs have developed within provincial cancer control agencies [Citation4]. The response to the cancer challenge was to bring together in the late 90s and early 2000s the cancer community. Over 700 cancer experts and survivors with full participation of the federal, provincial and territorial governments, and the cancer society met and developed the approach adopted [Citation5].

This article will focus on the development of an integrated multidisciplinary anti-cancer model, for a community hospital and its network in the province of Quebec. The organisation of the functioning health network and its adaptability to the specific needs of the cancer population will be discussed. The focus will deal with the evolving nursing role in the challenge of geriatric population, faced with cancer.

The history of the development of National Cancer Programs in Canada

The World Health Organisation, in the early 2000s, began advocating the implementation of comprehensive national cancer programs, as essential to reduce morbidity and improve the quality of life of cancer patients and their families everywhere in the world where the cancer burden was high or rising [Citation6].

The development of these national programs required, according to the report, careful planning and organisation surrounding the four principle approaches to cancer control, namely prevention, early detection, treatment and palliation. They envisioned many different models, some of which combined governmental and non-governmental partnerships. The common thread was the four ingredients felt necessary to establish cancer programs. Prevention refers to the elimination or minimisation of the exposure to the causes of cancer, and to the reduction of individual susceptibility to the effect of such causes. Tobacco control is one such example. Early detection refers to the awareness of the signs and symptoms to diagnose the disease early, as can various screening procedures that can lead to early detection. This coupled with treatment and palliation can lead to better quality of life for people with cancer.

In the US, National Cancer Institute is the world's largest organisation dedicated to cancer research. It is the leader of the National Cancer Program and provides leadership to the global cancer community [Citation7]. The National Cancer Centre Program was created in 1971, with the goal of establishing centres of excellence in research, clinical services and cancer prevention [Citation8]. It was this organisation that helped take up the WHO challenge in the US, and support the goals of cancer control.

In Canada, the federal government's role in health care involves the setting and administering of national principles or standards. In addition, areas of responsibility in health are health promotion strategies, illness prevention and education [Citation9]. With the aging population of baby boomers, the need to develop a national strategy for Cancer Control became essential. In the May 2006 federal budget, the government committed $260 million dollars over 5 years to implement the strategy. The strategy married the strength of the federal government and the provincial based health care management [Citation10].

Epidemiology of cancer in Canada

An estimated 171,000 new cases of cancer (excluding 75,100 non-melanoma skin cancers) and 75,300 deaths from cancer will occur in Canada in 2009 [Citation11]. Three types of cancer account for the majority of new cases in each sex: prostate, lung colorectal in males, breast, lung and colorectal in females. Lung cancer is the leading cause of death in both men and women. Colorectal cancer is the second leading cause of death overall.

The incidence and mortality rates are higher in Atlantic Canada and Quebec and lowest in British Columbia. Lung cancer incidence and mortality rates are highest in Quebec and lowest in British Columbia. Colorectal cancer mortality rates are approximately twice as high in Newfoundland and Labrador than BC. There is little variation in breast cancer rates across the country. Forty-three percent of new cancers and 60% of deaths occur in people 70 years and older. Cancer incidence is rising in young women aged 20–39. Based on current incidence rates, 40% of Canadian women and 45% of Canadian men will develop cancer at some time in their lifetime.

The Quebec Government's Program ‘Lutte Contre Le Cancer’

In Quebec, the need for cancer control was recognised as vital to the health of the population. Since the year 2000, cancer has become the number one cause of mortality in Quebec, surpassing cardiovascular disease. In 2004, 32.6% of all deaths were cancer related versus 27.8% for cardiovascular disease [Citation12]. In 2005, there were 37,400 new cancer cases in Quebec with a population of 7,475,000, and 25,600 deaths [Citation13]. The age adjusted incidence rates of cancer have remained stable in Canada, but there has been a 2% increase in new cases attributed in part to the aging of the population.

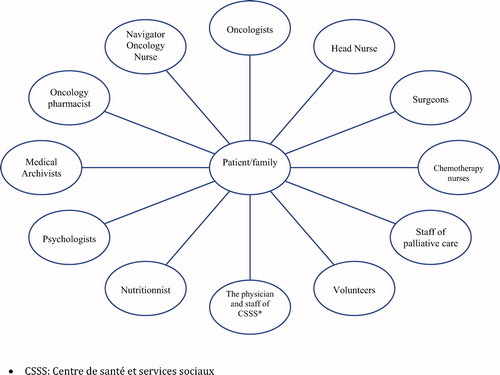

The development of the anti-cancer program in Quebec began in 1998, with the ‘Programme québécois de lutte contre le cancer’ [Citation14]. In 2004, the government committed to support and become part of the national plan over a period of 3 years. The program had to marry the desires of the population targeted in order to respond to their multiple health care needs across the spectrum. The priority of the population is rapid accessibility to health care services rendered with a personalised approach by competent professionals. Health care consumers want to be active participants in the decision-making process. The aspects of a cancer program must also provide a continuum of health care services that deals with everything from prevention to palliation () delivered in a multidisciplinary fashion within a framework of the aging population ().

The Quebec government established five major objectives for the program [Citation11]. The first objective identified was the local and regional organisation. The local organisation centred on a multidisciplinary team whereby the cornerstone is the oncology navigator nurse orchestrating the coordination of the program. The local team provides the spectrum of services and the manpower required to manage all phases of the program. The local teams are supported by a regional team for specialised service. The latter team is supported by a supra-regional team for supra-specialised services. This model allows for services to be provided directly to the patient, as shown in . This applies for all aspects of the program. It also provides for the geriatric services previously outlined [Citation3].

The second objective is to have the anti-cancer program follow the similar policies of the government's approach to all chronic disease. This implies placing a large degree of importance on prevention and screening. It also means collaboration among several other sectors, such as the environment, municipal affairs, and education among others.

The third objective is to make the system easily accessible at all phases of the process. This requires organisation and project development to achieve these objectives. The fourth objective was to allow the journey of a cancer patient through the different stages along the trajectory of care in a seamless manner. The fifth objective focuses on the need to ensure continuing medical education programs that allow physicians to acquire enhanced knowledge and skills in order to provide the highest standard of care to the cancer patient. Lastly, the objectives must be evaluated and changes made where indicated.

These steps coupled with the system of geriatric care management and efficient resources allow optimising the process concerning physical and psychosocial care in order to attain excellence of care.

The evolving role of cancer care nursing: an overview

Over the past 20 years, there has been a major shift in the delivery of health care services from the hospital toward the community setting. This transformation has prompted nursing to re-examine care delivery models to facilitate this transition from the acute care to the home setting [Citation15]. Thus, the continuum of care within the cancer trajectory that was previously controlled within a hospital setting has been reoriented to alternative modes of administering health care services required by the cancer patient within a non-traditional hospital setting. This approach favours the preliminary diagnostic tests, screening and preadmission workup on an outpatient basis within a hospital setting or clinic setting.

Thereafter, following hospitalisation for a medical treatment or surgical intervention, discharge planning is prioritised once the patient is medically stable and follow-up can be provided on an outpatient basis. This ensures a more rapid return to the patient's home environment thus allowing him to regain control of his daily life activities within a familiar milieu and supportive network. Concomitantly, if required, the cancer patient may return for day visits to the hospital for specific protocol treatment programs within a multidisciplinary approach. Most importantly, this paradigm shift gave way to a new vision whereby the emphasis was to improve coordination of care and accessibility to care by successfully integrating education, prevention, screening, diagnosis, and treatment [Citation16].

In order to meet the challenges with cancer care and the geriatric population within a comprehensive integrated model, there has been a steadfast commitment in the emerging development of new roles and the educational preparation required for nurses. Moreover, the management of cancer in elderly patients care justifies specialised training and continuing education for nurses. Specific skills for the administration of complex chemotherapy drugs, up to date knowledge on assessing potential drug interactions and side effect management, symptom management, pain management and psychosocial skills for assessing family dynamics and role changes when a family member is afflicted with cancer, are some examples of the advanced knowledge and skills required by nurses working with the elderly cancer patient.

Within the diversified roles that nurses assume, they are vitally involved in the education of patients, families, and peers and with advances in cancer care frequent reviews and revisions of patient teaching tools, methods, and materials must be continually maintained. Furthermore, bedside nurses are often faced with mounting demands and even with their best efforts, patient education, though essential, may be fragmented and incomplete [Citation17]. This is where the emergence of such roles as the oncology clinical nurse specialist, oncology certified nurse, oncology case manager, and the oncology navigator nurse can be of immense benefit to help respond to this growing demand and need of the elderly cancer patient and have a major impact in the delivery of optimum cancer care.

In Canada, oncology certification prepares nurses for such specialized role functions. Since 1997, the Canadian Nurses Association (CNA), through its certification examination process has recognised oncology nursing as a speciality. The Oncology Nursing Society in the USA has recognised the speciality status for 20 years [Citation18]. Thus, nurses that occupy such roles accompany patients and their families and support them throughout the long therapeutic journey and provide them with adapted information regarding the disease, treatments, and available resources [Citation19]. Older patients have unique needs because of their often complex medical histories, numerous drugs they are taking, their social situations, possible problems with cognitive dysfunction related to age, and general diminution of organ function that occurs naturally in the older population [Citation20].

The overall strength in the evolving roles of geriatric cancer nursing ensures both continuity of care and a migration to an interdisciplinary team approach in the delivery of care to patients and their families. Interdisciplinary teams work interdependently with the common objective being to provide a wide range of services to meet the specific needs of the geriatric cancer patient, including physical and psychological support. Such teams create a working synergy whereby power is shared and the focus is outcome patient-centred. Depending where the patient is along his disease trajectory, this approach favours different nursing roles to work interdependently and collaboratively thereby ensuring that nursing is utilised to its maximum benefit for patient care.

In 2005, the oncology nurse navigator (ONN) role was created in Quebec, Canada, within this integrated care network perspective of the Quebec Cancer Control Program. Working on the frontlines and side by side with physicians and other professionals, trained nurse navigators play a central role in providing supportive care and expert guidance, assisting the patient and family navigate through the health care system and providing information and education.

In general, individuals with cancer and their families feel powerless, without resources, abandoned to their own devices, and do not know who to turn to when they have questions [Citation19]. They are struggling to navigate the cancer care health system in order to receive timely and appropriate care. Thus, nurse navigators become the pivotal link with other health professionals involved in the care of the cancer patient as well as with alternative resources within the community. In this respect, they serve as the liaison between the patient and family and the healthcare team and are an integral component in cancer care delivery.

Nurse navigators assist patients with improved access to care by providing early contact with resources and education. They are helpful to the multidisciplinary team for the cohesive continuum of patient care from diagnosis to survivorship [Citation17]. This continuous and comprehensive approach avoids fragmentation of care and extends from across different phases, from diagnosis through treatment, follow-up and palliative care. The nurse navigator's extensive oncology knowledge and her skills are critical in providing patient education, teaching, advocacy and communication at all levels.

The complexity of cancer, cancer treatments and potential side effects of the treatments, coupled with other age-related conditions are issues facing health care providers, such that it becomes important to have a clear understanding of the changes of aging and the unique needs of the older individual [Citation21].

Because the cancer care continuum follows several different paths, nurses are in a privileged position as the primary health care resource for providing information that guides the process of clinical decision-making and interdisciplinary collaboration in order to achieve comprehensive patient and family-centred care. Although the nurse cannot give back to the elderly patient his optimum level of health, she can, nevertheless, assist the patient in achieving a certain level of emotional wellness. The meaning of living with cancer in old age is individually experienced and thereby affects each person in a different and unique manner. Thus, it is vital for nursing as well as other health care providers to encourage the geriatric patient to describe his or her illness experience in order to gain an increased understanding about what is meaningful and to initiate the appropriate care interventions.

Implementation of the model in a community hospital

In 2005, Santa Cabrini Hospital in Montreal, Quebec (Canada), embarked on the challenging journey of reorganising its oncology services in the hospital within the framework of the Quebec Cancer Control Program. Santa Cabrini hospital is a 369 bed community-based hospital that treats about 3000 cancer patients annually, in the oncology clinic alone, provides curative and palliative surgical care to a large number of patients 60 and over. The majority of these patients are treated on an outpatient basis following their investigation and medical or surgical treatment. In the outpatient setting, they are referred to the oncology clinic and followed by a multidisciplinary team. The nurse navigator role was created to respond to the vision and recommendations emanating from the Quebec Cancer Control Program Reports (1997, 2002, 2004). In 2005, the Quebec Regional Health Agency, announced its plan of conducting hospital visits in order to assess the hospitals where cancer patients were being treated and determine if they met the criteria for being designated as a cancer control centre on a local, regional, or supra-regional basis. In March 2006, the visit was conducted at Santa Cabrini Hospital and the hospital received a favourable response and was officially recognised as a local cancer control centre. The necessary infrastructures were solidly in place and the challenge we had was to consolidate and develop further our links and partnership with the integrated health network in the community, including home care services, health clinics and cancer resources. This would ultimately ensure that the cancer patients treated at our hospital would be accompanied and supported by the oncology nurse navigator (ONN) for continuity of care services throughout their disease trajectory. The interventions by the ONN can take place at any of the following moments: announcement of the cancer diagnosis, first visit for a consultation with the oncologist, chemotherapy treatments, hospitalisation, remission, reoccurrence, or palliative care. The ONN serves as the liaison for the patient both within the hospital setting and the community or outpatient setting by guiding the patient through the health care system and ensuring access and continuity of care throughout the cancer trajectory.

The proactive approach of the Quebec Cancer Control Program ensures a continuum of services from early screening, prevention, diagnosis, treatment and palliation, within an interdisciplinary framework model. Consequently, this program has paved the way for new approaches in the management and delivery of health care services for individuals afflicted with cancer. One of the major changes resulting from this program and impacting on the care of cancer patients across different life spans has been a shift from a more centralised approach within a hospital setting toward the provision of health care services on an outpatient or home care setting. Thus, once the acute phase in the hospital is terminated, infrastructures provide patients either with the opportunity to be reoriented at home or within other community health care services available. The benefits of such a program result in an elevated level of care for the elderly for they have the availability of an expert health care resource person that can steer them in the right direction and provide much needed answers to their questions thereby reducing anxiety and promoting a sense of personal control during the course of their disease trajectory.

Most importantly, the emergence of the oncology navigator nurse role has supported and enhanced the significant complementary role between nursing, medicine, and other allied health care professionals. The current status of the Quebec health care system and the escalating trends in cancer coupled with increased life expectancy will inevitably require a need for more trained navigator nurses with expertise, experience, and competency.

The complexity of a patient-centred multidisciplinary, multifaceted cancer program has changed the medical role in cancer management while at the same time maintaining speciality driven expertise has become an essential part of the process. Continuing medical education, upgrading of first line physician training, development of expertise that cross traditional medical boundaries are essential to the integration of the medical, nursing and paraprofessional communities of health care delivery. The development of the networks of health care in Quebec as previously described [Citation3] have made the medical transformation easier, as has the encouragement of education and development as part of the plan. The development of expertise in paediatric oncology and geriatric oncology, the encouragement of support groups and support at the local, regional, and supra-regional level have allowed integration of community hospitals, outlying community institutions, secondary and tertiary care centres to work in a collaborative integrated manner.

The scope of the geriatric population poses the greatest challenge to the medical community, since the spectrum of the aging population must be considered in the algorithm of treatment. The fit, elder population in the greater than 85 age range, and the vulnerable aging population with cognitive impairment are the extremes, but the challenges lie all along the continuum. Who to treat, who not to treat, how aggressive to be, ambulation, cognition, longevity factors all come into play and require expertise. The development of combined teams with oncology and geriatric expertise, development of ethical infrastructures in hospitals, and the integration via the navigator nurse of the two solitudes (aging and cancer) are emerging as the support tools making the transition easier. The demands on medical, nursing and paraprofessionals to understand aging in all its facets will grow as the population continues to age.

Conclusion

The universal health care model in Canada, managed by the provinces has allowed for the development of a Cancer Control Program at the local community hospital and local health network level. The collaboration of all levels of the health sector is essential to the development of the mandates, goals, objectives and resources needed to allow for the development of the various programs, such as the anti-cancer program in the geriatric population. It is however, at the local community network level, and local community hospital level that these programs become realities.

Acknowledgements

The authors want to express their gratitude To IRENE GIANNETTI, Director General, Santa Cabrini Hospital, Montreal, Quebec (Canada), for her support, guidance, and helpful suggestions.

References

- The Canadian Cancer Society. Progress in cancer control over the past few decades. The Canadian Cancer Society; 2010.

- Shubert C. Functional assessment of the older patient with cancer. Oncology 2008;22.

- The Quebec government's approach to the vulnerable aging population. Aging Male 2009;10.

- Public Health Agency of Canada. Progress report on cancer control in Canada. Public Health Agency of Canada; 2004.

- Public Health Agency of Canada. Media backgrounder: the strategy for cancer control. Public Health Agency of Canada; 2006.

- National Cancer Control Programmes. Policy and managerial guide. 2nd ed. WHO Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data. World Health Organisation; 2002.

- The NIH Almanac. National Institute of Health.

- Birkmeyer Nancy JO. Do Cancer Centres designated by the National Cancer Institute have better Surgical Outcomes. Cancer 2007;103:435–441.

- Canada Health Services Profile. Organisation and management of Health Systems and Service Programs. Division of Health Systems and Services development, Pan American Organisation; 2000.

- Canadian Strategy for cancer control: Let's make Cancer History. Canadian Cancer Society.

- Canadian Cancer Statistics, Canadian Cancer Society, Statistics Canada, Provincial/Territorial Cancer registries, Public Health Agency of Canada; 2009.

- Direction de la lutte contre le cancer : orientations prioritaires 2007–2012 du Programme québécois de lutte contre le cancer.

- La Lutte contre le cancer au Québec : vers une mobilisation générale de toutes les parties prenantes. Rapport finale présenté à la Coalition Priorité Cancer au Québec Avril2005.

- Ministère de la Santé et des Services sociaux. Pour lutter efficacement contre le cancer formons équipe-Programme québécois de lutte contre le cancer. Comité consultatif sur le cancer; 1998.

- Joynt J, Kimball B. Innovative care delivery models: identifying new models that effectively leverage nurses. Health Workforce Solutions; 2008. White paper submitted to: Robertwood Johnson Foundation. Human Capital Team.

- Hayter CR. Historical origins of current problems in cancer control. Can Med Assoc 1998;1735–1740.

- Swanson J, Koch L. The role of the oncology nurse navigator in distress management of adult inpatients with cancer: a retrospective study. Oncol Nurs Forum 2010;37:69–76.

- Fitch M, Mings D. Cancer nursing in Ontario: defining nursing roles. Can Oncol Nurs J 2003;13:28–35.

- Fillion L., de Serres M., Lapointe-Goupil R., Bairati I., Gagnon P., Deschamps M., Savard J., Meyer F., Bélanger L., Demers G. Implementing the role of patient-navigator at a university hospital centre. Can Oncol Nurs J 2006;16:11–17.

- McCaffrey Boyle. Realities to guide novel and necessary nursing care in geriatric oncology. Cancer Nurs 1994;17:125–136.

- Kanakie, ML, Tringali, C. Promoting quality of life for geriatric oncology patients in acute and critical care settings. Crit Care Nurs Q 2008;31:2–11.